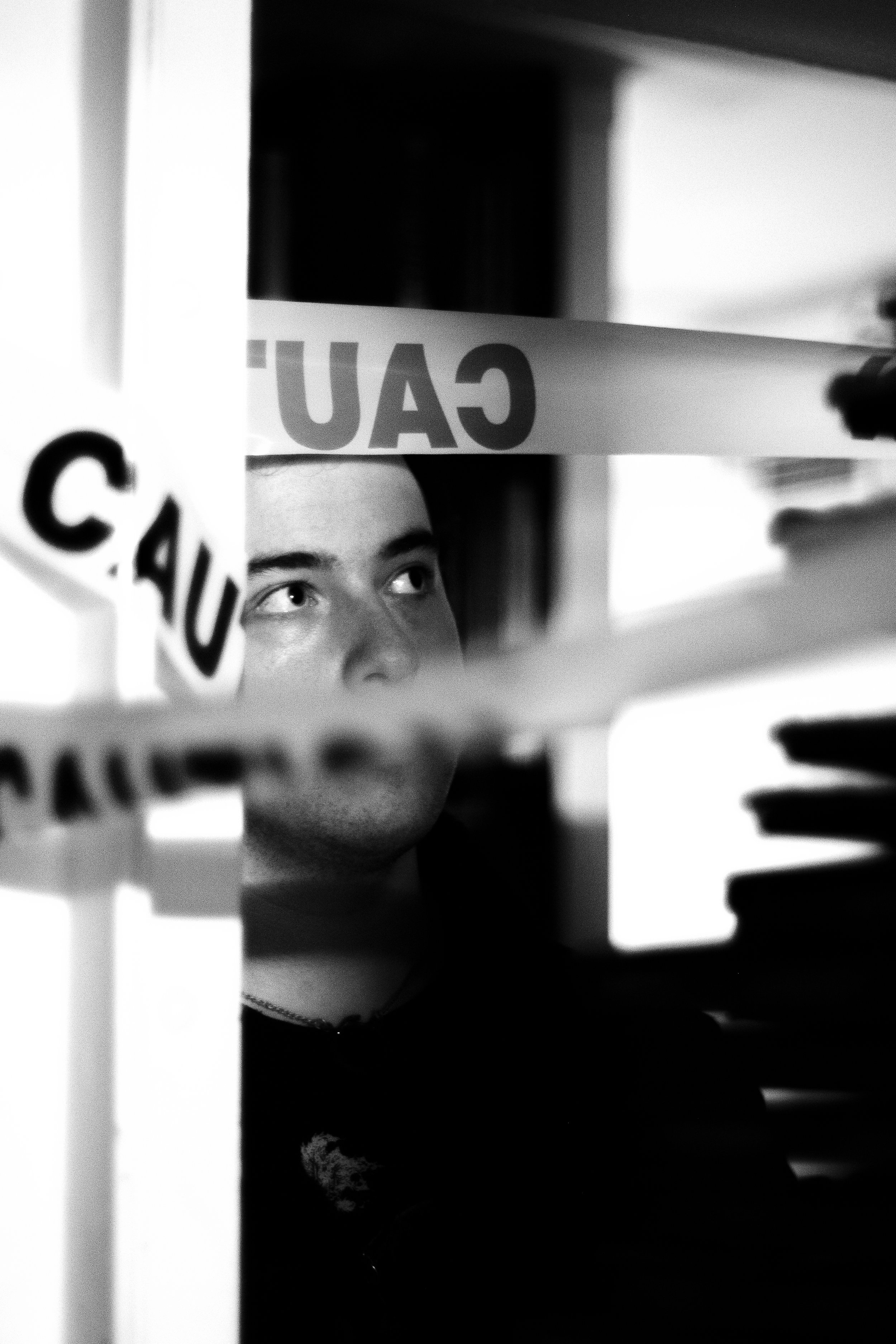

Feature by Anushka Pai

Photos by Natasha Last-Bernal

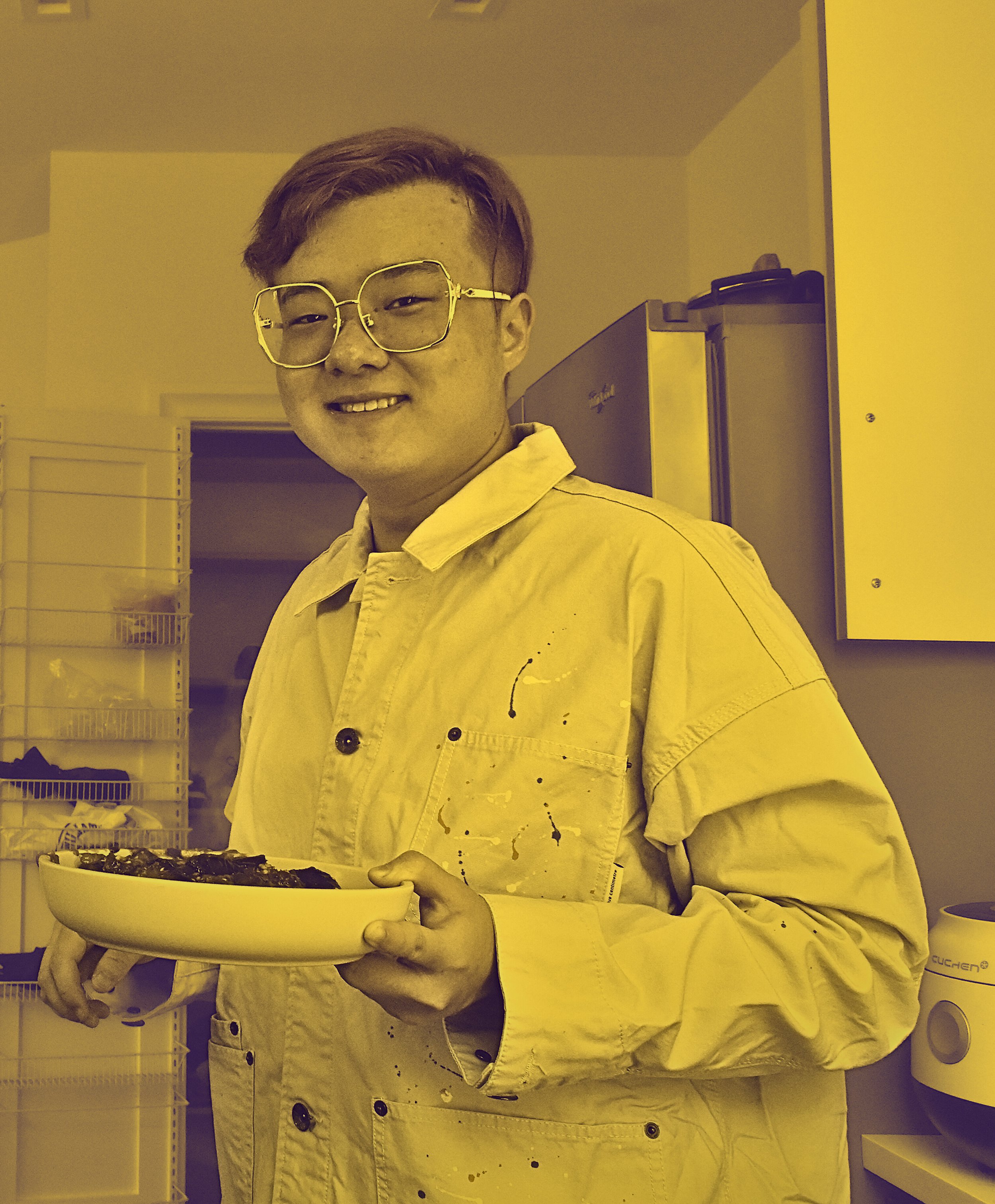

Two weeks ago, I hosted an unexpected guest in my dorm. Dressed in her best knitwear and draped in pearls, the doll lay on my dresser, glaring. After three days under her watchful gaze, I walked her across the hall to the room of Charlotte Lawrence (they/she), BC’ 25. As an architecture and environmental science student, Charlotte is passionate about the intersection of design and sustainability. While they often spend their time sketching and doing graphic design, their most beloved hobby is crocheting.

The doll, resting on a crochet pillow (2024

The doll is one of Charlotte’s many projects, made over several months. Since then, she has quickly accumulated a collection of jewelry and crocheted outfits, which she routinely alternates.

Having lived together for the last four years, I have witnessed Charlotte’s creative process from beginning to end, ten times over. The doll began as a textile, evolving into a head, body, and limbs. Starting each project without a blueprint, their vision materializes as they work, turning textiles into dolls, dresses, and accessories.

Tapestry made of scrap yarn (2022) and headphone cover made of second-hand alpaca yarn (2022)

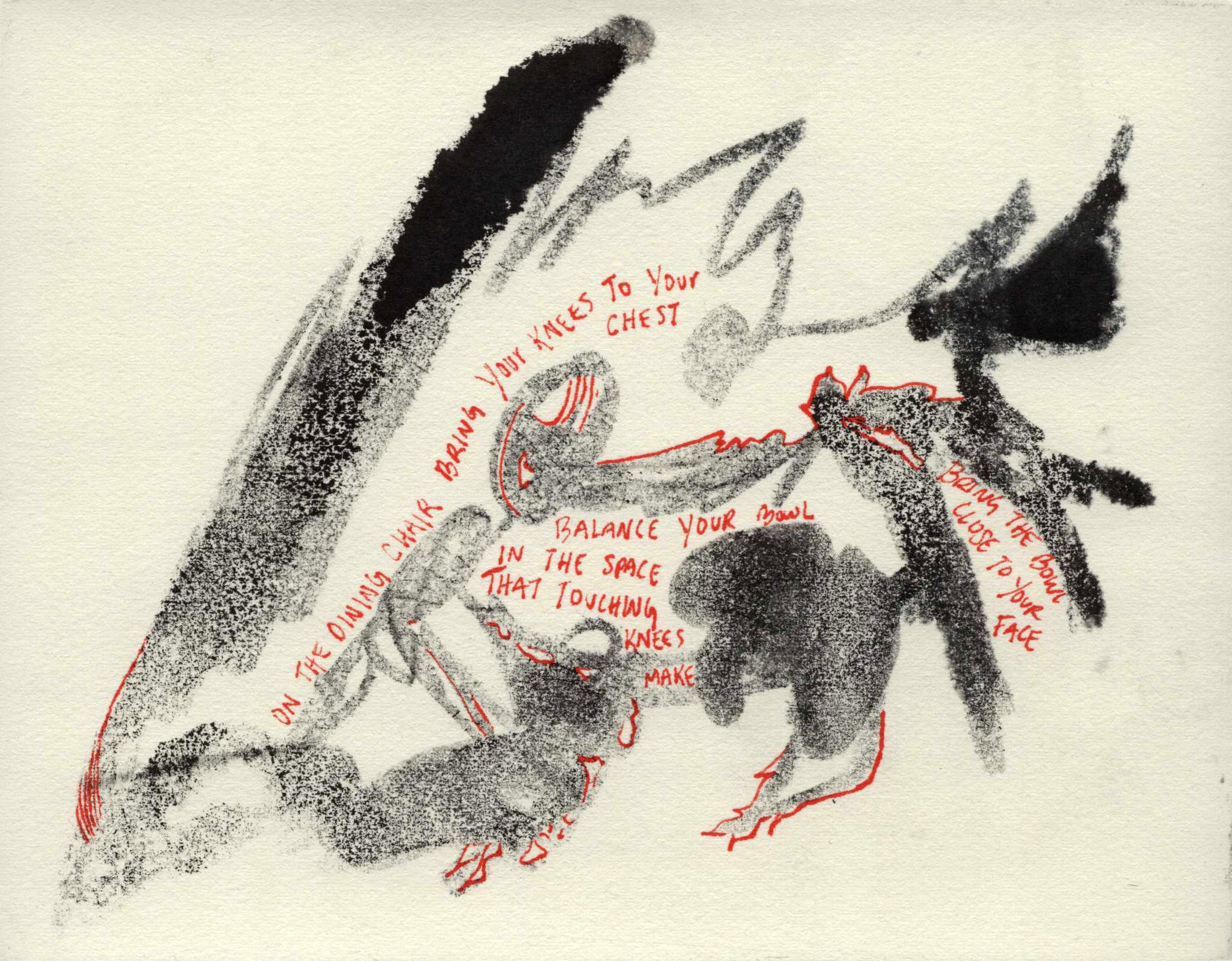

“It’s kind of hard to pinpoint when I decide what it’s going to be because crocheting has always been more about the act of doing it than making something for me. As a textile grows, it kind of starts to take shape into something, and that’s when I realize what it can be,” said Charlotte.

Charlotte allows their mind to wander freely while crocheting. The repetitive motion of creating stitches provides them with a sense of relief. More than once, I have tried to call out to Charlotte from across the room, only to be met with silence. Lost deep in thought, and crochet, it would take me numerous tries to get her attention.

“I’ve gotten to the point skill-wise where my mind can really wander anywhere and my hands just take over. I’m half focused on the motions and trying to get consistent stitches, but for the most part, I just let my mind wander wherever it goes. I’ve found myself in a meditative state before, where my mind is completely detached from the movements of my body,” they stated.

Charlotte began crocheting at the age of 5, learning the craft from their aunt. Over time, it became a way to bond with family, relieve stress, and pass time in their hometown, Kansas City.

“My Aunt Lizzie taught me how to knit when I was young. She’s a fiber artist as well. I got really into crochet when I was about 15 and my math teacher was teaching a crochet class. When I took that class with her, I fell in love with it all over again. Once the pandemic hit, it became a daily activity for me,” they said.

While at home, Charlotte spends their time crocheting with their sister, Ella. Having learned most of their technical skills from her, Ella has played an important role in Charlotte’s artistic development.

“Crocheting with my sister is the way we bond. We often sit side by side, put on a show, and crochet for hours. It’s the most comforting feeling. She is also the one who has taught me the most over the years, and I’m grateful to have someone so creative to guide me,” Charlotte stated.

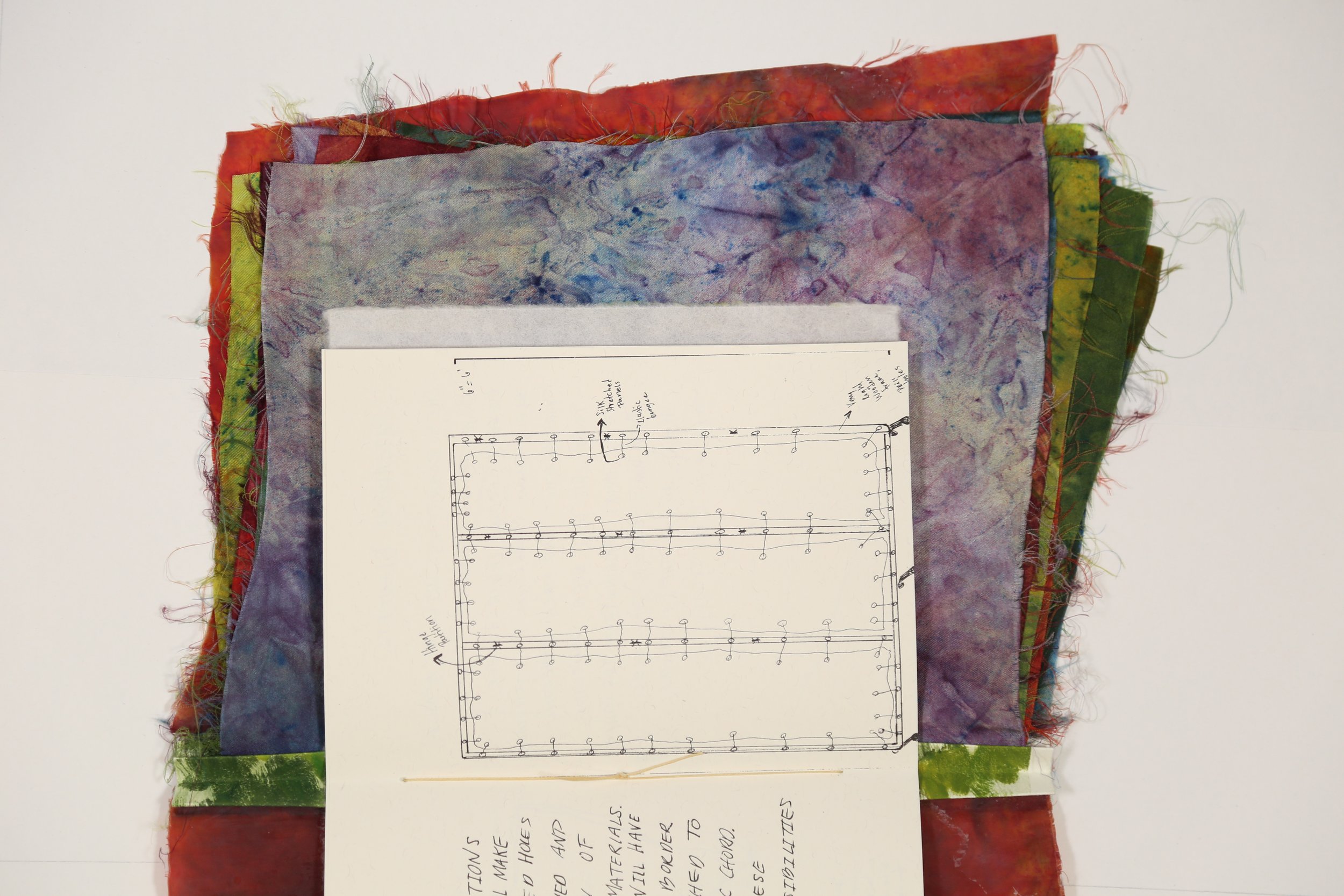

After entering college, Charlotte’s background in sustainability began to influence their creative process, inspiring them to change how they consume and dispose of materials.

“The more I learned about sustainability and the more classes I took, the more environmental consciousness came into focus in my passions. I used to use acrylic yarn because it’s so widely available. When you use it, it sheds all of these little fibers. However, after taking classes in environmental science, I realized that the shedding of the yarn was basically microplastics and that every time I disposed of little scraps of yarn, I was just putting those chemicals back into the environment.”

While Charlotte almost exclusively purchases her yarn from a second-hand store in Kansas City, she just as frequently reuses materials from previous projects. On their shelf, sit two large bags of old designs, textiles, scraps, and balls of yarn. Many of these materials date back to freshman or sophomore year, made while holed up in our dorm. Often, Charlotte revisits old projects, reworking them into something new. Likewise, she incorporates scrap yarn into her pieces, ensuring nothing goes to waste.

Halter top made entirely of scrap yarn (2022)

“In the machine age, we’ve all become somewhat obsessed with perfection–artistically, design-wise, and functionally. Mechanizing forms of creativity, like crochet, generates a lot of waste. It’s weird to throw that stuff away when you can just use it, even if what it makes isn’t completely perfect,” said Charlotte.

Embracing the ‘imperfections’ of hand-stitched crochet, Charlotte gravitates toward organic shapes and free-flowing lines. In their clothing, these preferences manifest as swirling patterns, unique silhouettes, and alternating stitching. Working without a pattern, each piece is wholly individual.

Mesh halter backless top, made from second-hand alpaca yarn (2023)

After dropping several hints to her, Charlotte gifted me a pair of bright pink fingerless gloves, which she had made earlier that year. One of the reasons that I liked them so much was because, like so much of Charlotte’s work, the gloves were made with complete spontaneity, yet came together so cohesively that it was hard to imagine it wasn’t planned.

“I’ve always been drawn to organic shapes because it feels the most natural to me. It also just kind of happens when I let my hands do the work without interfering,” they stated.

Purse made from acrylic yarn, an old iPhone charger, and a necklace (2024)

Charlotte emphasized that, above all, it is important to them that crochet remains enjoyable, free from becoming something they ‘have’ to do. So long as it remains fun, they plan to continue crocheting for the rest of their life.

“Crochet is one of the few things in my life with no deadline. I can pick up any project I want, but I don’t feel pressured to do so. My timeframe is all of eternity, or at least until I get severe carpal tunnel”

To learn about Charlotte’s latest projects, visit @c.lawmachine on Instagram.