Feature by Angel Wu

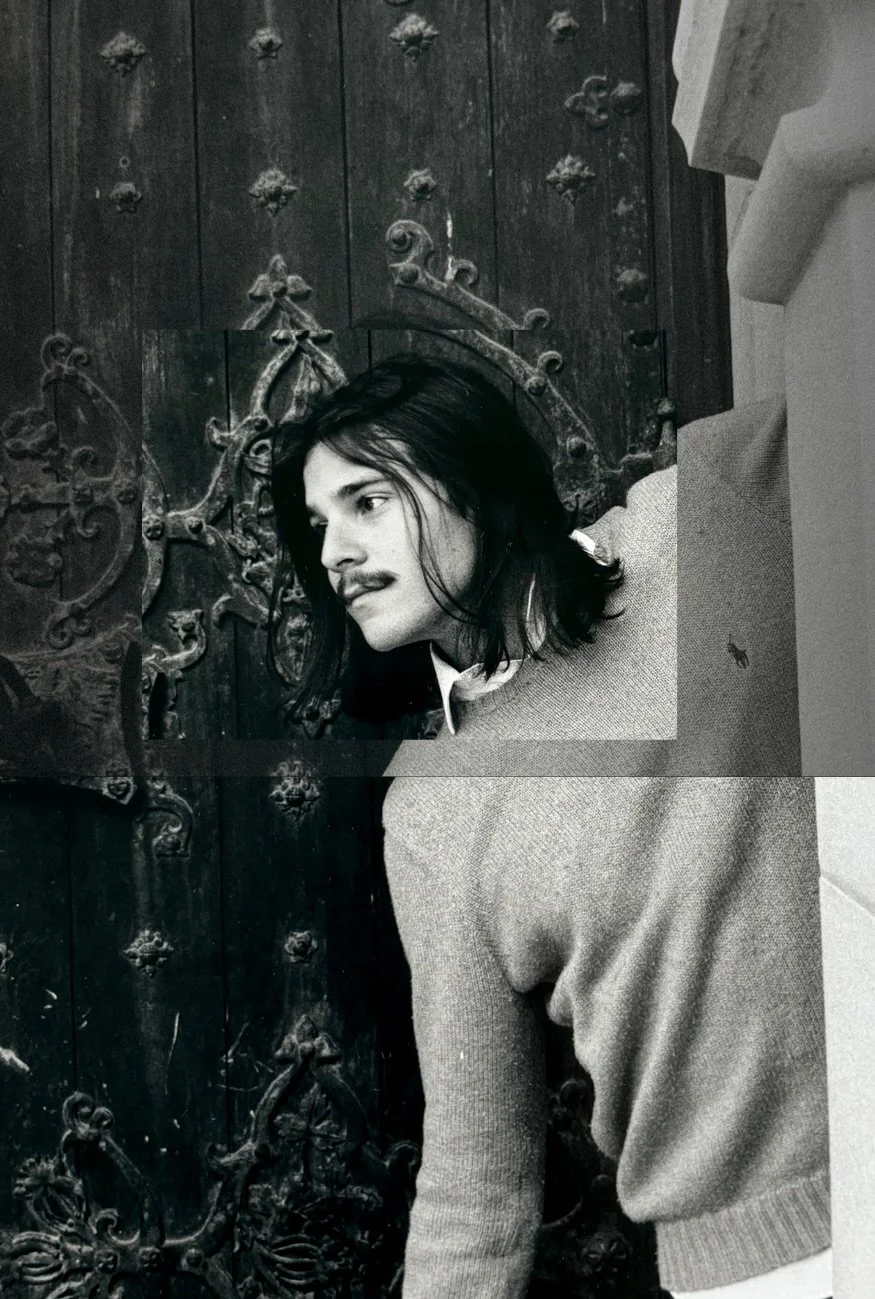

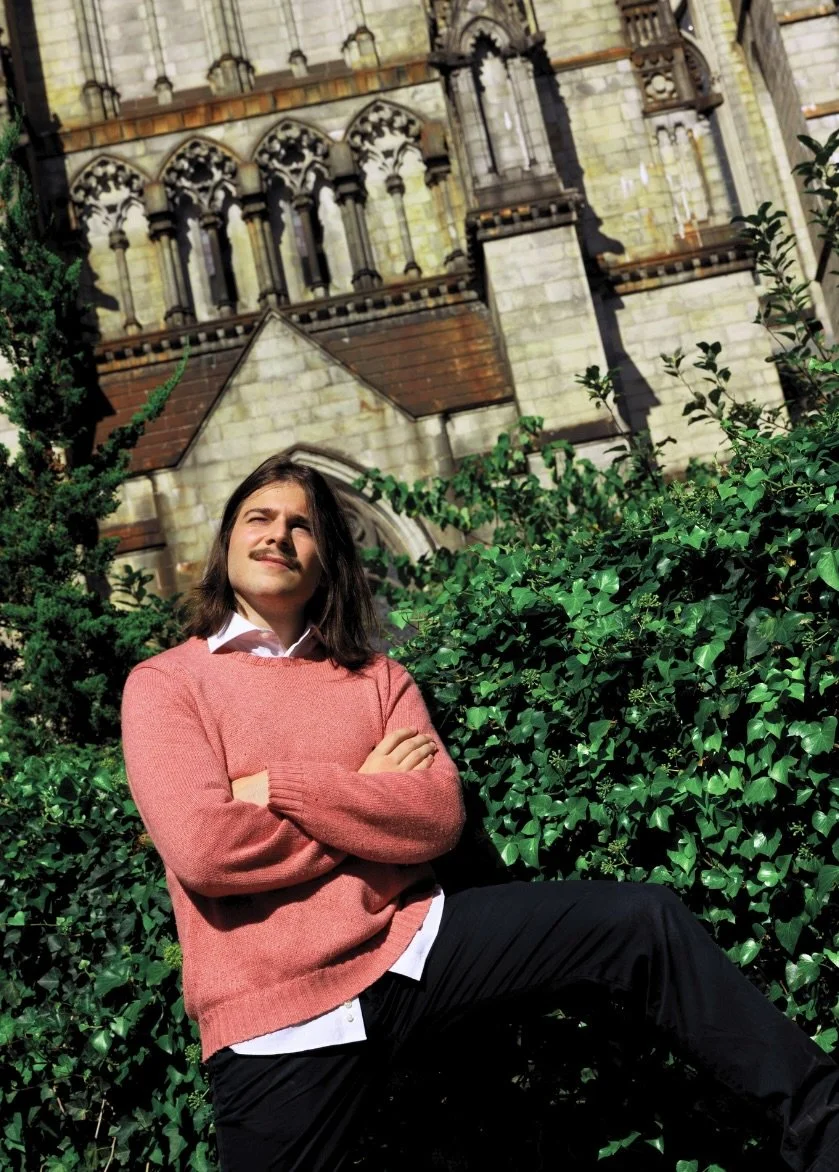

Photos by Alec Stangle

Yuhan Zhao (BC’ 27) studies Political Economy and Art History at Barnard College. She works with a variety of mediums, including painting, sculpture, and public art. Her pieces often poignantly explore gender, East Asian culture, and the locality of her works in relation to their sites.

Before entering the café where Yuhan and I had agreed to meet, I paced outside of Dodge for a while. We’d exchanged a few rounds of Chinese pleasantries over text; she’d been incredibly easy to communicate with and very lenient with her schedule.

We hadn’t actually planned on conducting the interview at Dodge that day. After a brief kerfuffle of more pleasantries where neither of us could decide where to go, we settled on a fairly public space: the tables right outside Dodge.

Our conversation began among sirens, the rustling wind, and a very persistent house sparrow. It felt like the whole city was speaking alongside Yuhan.

...

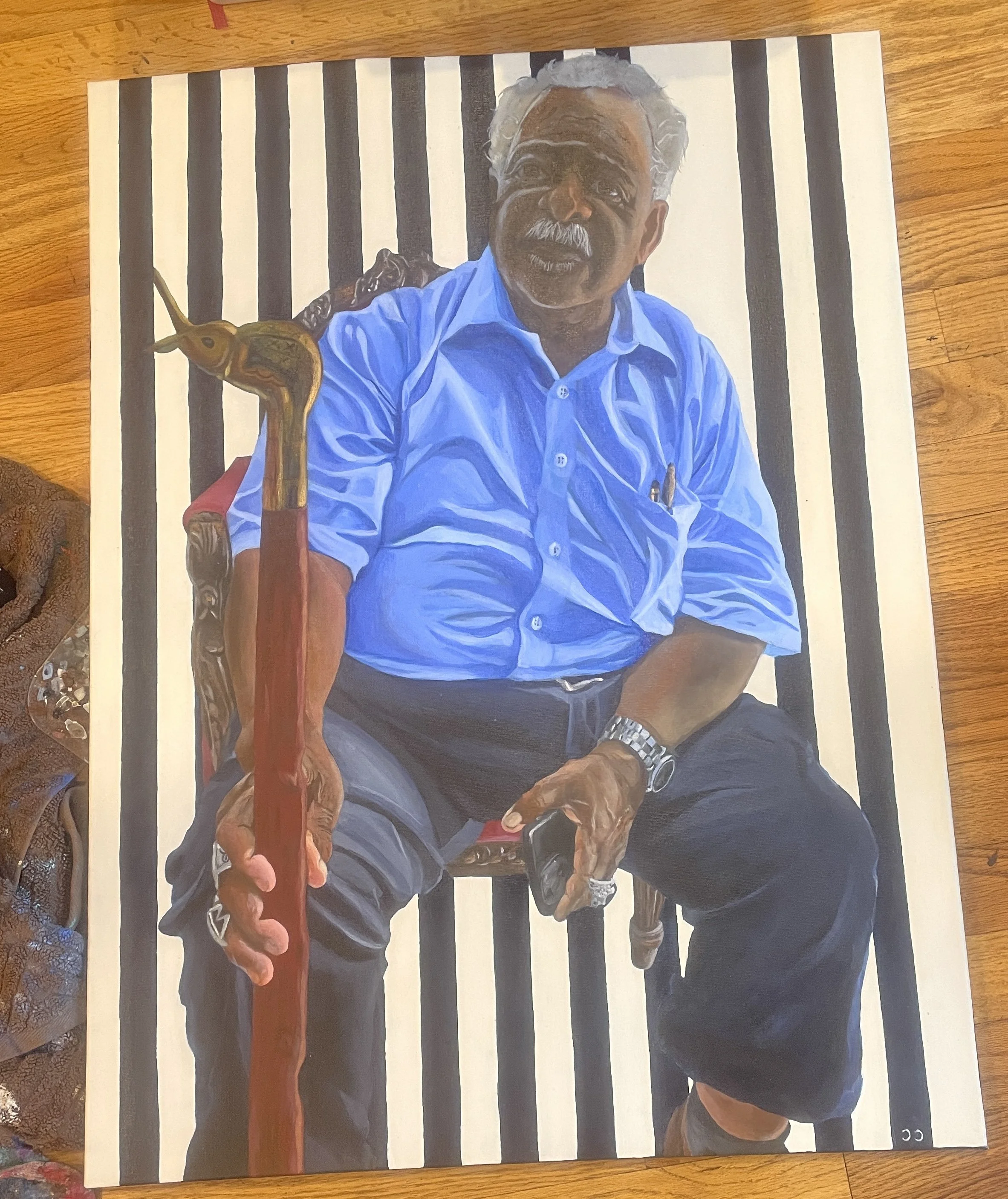

With a varied portfolio ranging from massive public installations to acrylic, watercolor and pastel paintings, Yuhan’s artistic journey seems difficult to summarize.

Driven by her own sense of identity, her art has explored themes like gender, environments, and East Asian culture. In the past few years, she’s been mostly pre-occupied with public art.

“When I first started out, I liked expanding the size of my works,” she said. “Regardless of whether it’s paintings or installations, [larger works] tend to have a very striking visual effect.”

However, she only began her foray into public art when she realized that larger works “have an inherently stronger connection to the public.” Ever since then, she’s been interested in exploring how art interacts with its audience and environment.

In fact, one of Yuhan’s primary concerns with her art is its locality: art’s connection to the land, culture, and people that it is situated in. Early on in our conversation, she also mentioned a classic quote from filmmaker Trinh T. Minh-ha: “I do not intend to speak about; just speak nearby.” Minh-ha is describing a complex idea that discusses how the artist should situate themselves in relation to their art; how they should portray subjects that they do not completely identify with or subjects that they identify with too closely. Trinh T. Minh-ha later clarified in an interview that art based in speaking nearby “does not point to an object as if it is distant from the speaking subject or absent from the speaking place.”

This philosophy is central to how Yuhan approaches her subjects. They’re rooted in the cultural and physical spaces they belong to, and Yuhan often interacts closely with these spaces in order to create her pieces. Perhaps with this idea in mind, she found it initially easier to portray subjects that were already close to her.

Yuhan explains that she often draws inspiration from mundane events that happen in her everyday life. For instance, her work “Chastity Arch (牌坊)” is a remarkable installation made out of roughly 300 cut-up secondhand books. It resembles an ancient type of Chinese monument erected for wives who remain virtuously unmarried after their husbands’ deaths. Each book is titled with deeply misogynistic advice for women: “Marry the Right Husband, Change Your Life,” “Women: You Should be Gentle All Your Lives.”

The tragedy? Yuhan tells me these books were repeatedly read and heavily annotated.

Chastity Arch (牌坊)

Yuhan’s inspiration for this project partially came from seeing a community poll for the “Most Beautiful Army Wife” on Chinese social media. She recounts the details of the poll to me with vivid accuracy: the women were ranked on what kind deeds they did, what part of the army their husbands were from, and how many elders they took care of. “It appalled me,” she gestured, “to see something like that in this day and age.” To her, it represented the long past of women being only memorialized for their “virtues” as loyal wives and caring mothers: something that should have disappeared with the ancient laws that subsumed female agency under male needs. She added, “Though people don’t erect chastity arches anymore, they persist in other forms.”

In talking about this piece, Yuhan also noted that the process of choosing a medium of expression is extremely important to her. She puts careful consideration into whether each step in her artistic process serves an ideological purpose.

“To cut up” versus “to grind [the books into pulp]” delivers distinctly different messages, she points out.

I think I understand why she insists on this step of the process. Words seem so light by themselves, but she described the books (that have piled generations of misogyny atop one another) as being harder to cut than wood. It’s such a physical way to represent the weight of the layers of expectation that have been placed upon women, and it’s also reminiscent of how women have had to objectify and sculpt themselves to fit within these virtuous standards.

Speaking nearby is also very much related to the writer’s equivalent of “showing a story” versus “telling a story.” Yuhan seems to be very invested in the act of “showing.”

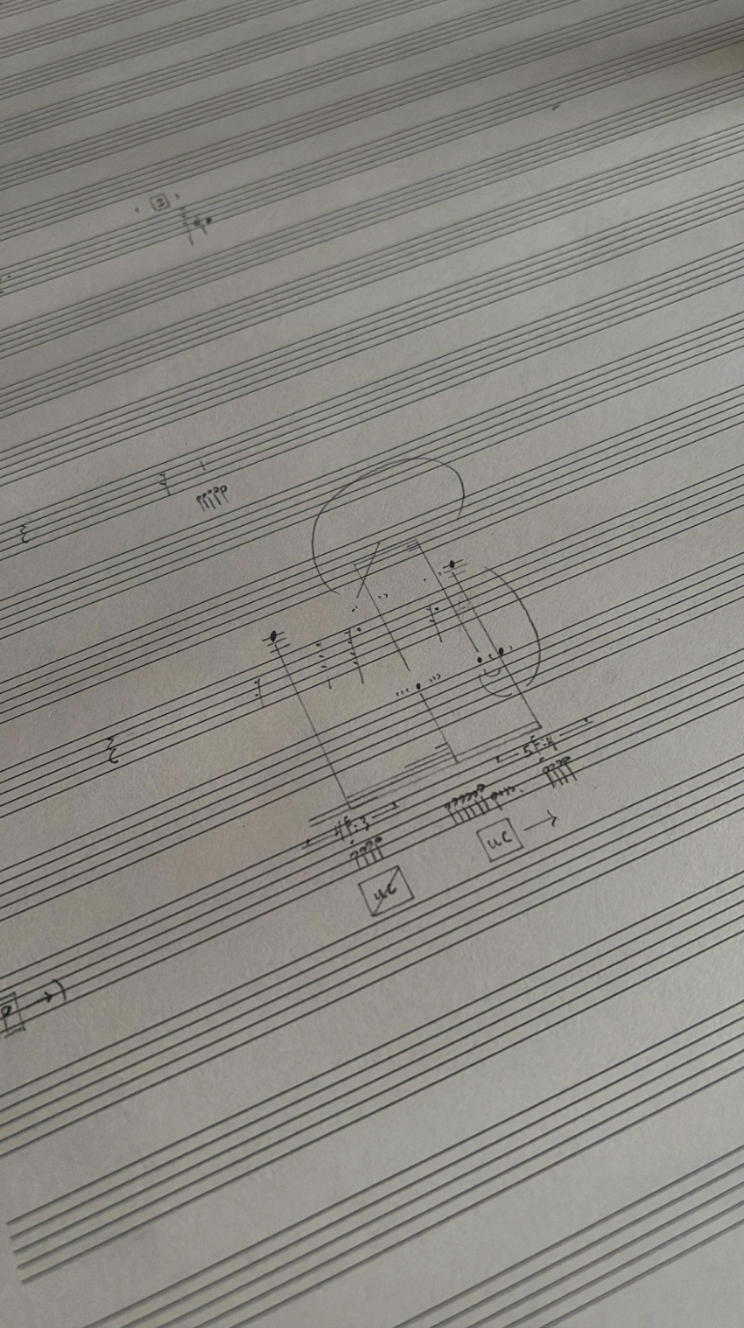

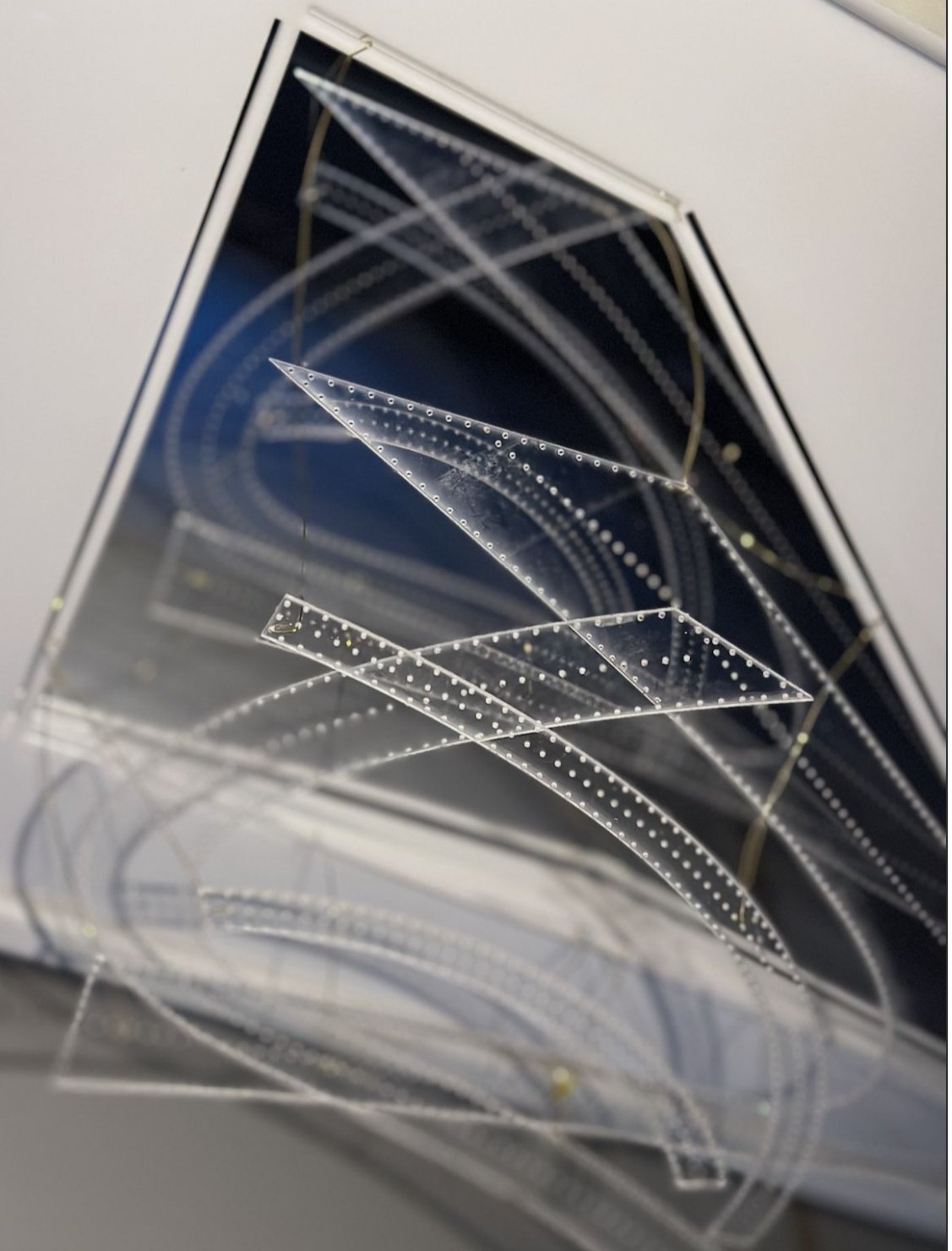

When I asked her about any particular process of creation that was especially interesting or memorable to her, she spoke about creating “Soil and the Ghost.” It’s an installation created at the Yale Norfolk School of Art Program. Taking inspiration from Norfolk’s wartime history of industrial manufacturing, the installation consists of a series of unfired clay pieces made from locally sourced clay. Chosen for its strong connection to the locality of Norfolk, Yuhan notes that leaving the clay unfired was a crucial step, as it would allow for the material to erode and merge back into the land it came from. It’s a process that speaks nearby to the industrial history of Norfolk by illustrating how things are made and unmade.

Soil and the Ghost

For Yuhan, this was a grounding experience that helped her better understand the landscape of Norfolk. She vividly describes the process of having to venture into the mountains to painstakingly look for soil to make into clay. It’s a drastic departure from the materials she has used for other works — which tend to already exist in some other form. “It’s different from using something like planks, which are already pre-made for you,” she clarifies. “I found it to be a particularly interesting experience.”

Created in 2025, “Soil and the Ghost” happens to be one of Yuhan’s more recent pieces. Because she perceives her art as something that constantly evolves with her identity, her artistic subjects have varied as she continues to learn and change.

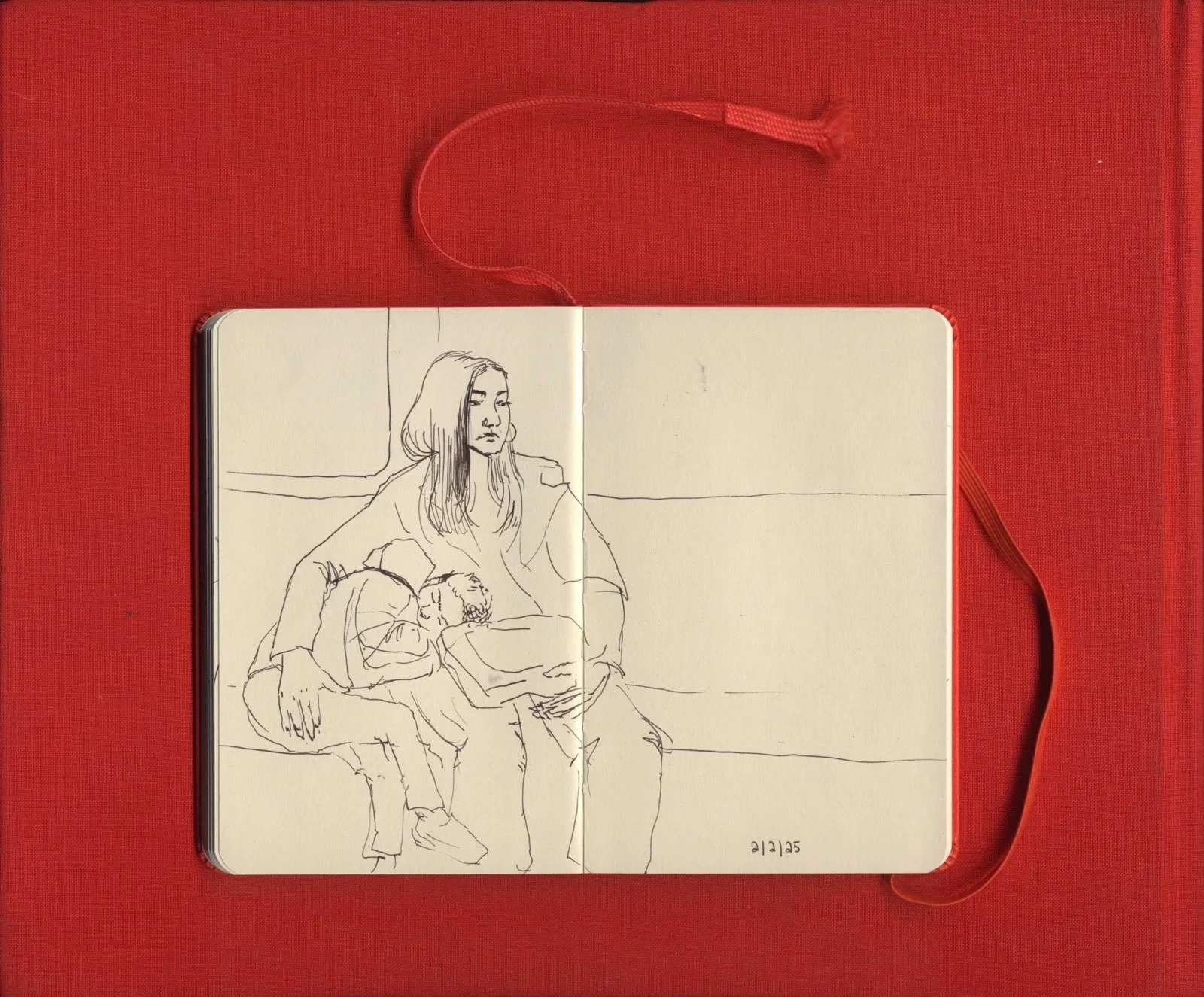

When I asked if she felt like there was a piece that was the most representative of her, she laughed and said it was her current one (which is a work in progress). Watching spiders and other insects in her old New York apartment, she’s been thinking about the creatures that originally occupy a space. She tells me that she’s still in the stage of “sawing wood.”

At this moment, Yuhan seems to be at a period of uncertainty in her artistic career. Though her capacity for exploration has allowed her to establish a hugely varied artistic range, it’s also created feelings of stagnation and boredom. She jokingly says that if she does something over three times, she gets bored of it.

“I know many mature artists tend to have established forms of expression, but I’m not sure if I want to stick with public art,” she states. “In the future, I might take up public art, or painting, or something else. I don’t know yet.” In fact, Yuhan doesn’t feel like art should be the thing that purely defines her. She’s equally influenced by her major in political economy; and she can’t envision art as being the only thing she does. “Art is a product of my life, but not everything in my life revolves around art,” she asserts. It’s true. Yuhan is evidently not an artist who is ever truly defined by a category of her identity. It’s her positioning of herself to her art that allows her to “speak nearby” on so many subjects so aptly. As our interview ends, the city’s voice swells as hers fades. Here, in New York, there’s still so much for her to “speak nearby” to.