Written by Katharine Lee

Photos by Grace Schleck

As a child, I would hide inside the clothing racks in department stores while waiting for my mother to finish her shopping. I spent many afternoons enveloped in rising clouds of dust and the soft, downy curtains of fabric. Occasionally, someone would remove a blouse from the rack, illuminating a hand, a torso, and a brief, thin sliver of light. For those who didn’t care to look too closely, I remained unseen — possessing, for a moment, the illusion of invisibility.

Meinzer’s work reminded me of this memory: the temporary shelter from the external world, the desire to seek privacy in public spaces, and the preciousness of self-indulgence. Whether through sculpture, printmaking, or textile design, Meinzer and their objects aim to return bodily agency to the user – a process entangled in paradoxes, and in the acquisition of new consciousness.

Screen

Meinzer’s dislike of machines, including cell phones, meant that the interview almost didn’t happen. They had texted the wrong number, agreeing to meet in Hungarian to chat. Later, Meinzer mentioned their “book of inconveniences, which is basically just a book of things [they] hate.” I imagined a page dedicated to cellular devices, expounding at length over the futility of technology, and the word-swallowing void into which Meinzer’s text had disappeared, unopened.

We did end up meeting, after some last-minute relocation, on the first floor of Dodge, due to Hungarian’s perpetual lack of seating. I first noted the firmness of Meinzer’s handshake. At the time, I didn’t know about Meinzer’s love of color, which they attributed to their legacy of working with painting. They were dressed in black and white, a juxtaposition of colors they enjoy, inspired by their work with inks and dyes at an internship for a screen printer. There, Meinzer discovered their secret superpower: someone could point to a computer, say, “I want this color,” and Meinzer would mix it perfectly, despite never having taken a formal color theory class.

“Tell me about yourself” revealed several more important facts about Meinzer: they’re from Austin, Texas; their favorite food is dino nuggets and Diet Coke (although “it's actually pretty hard just finding dino nuggets down here, so I really struggle with that,” Meinzer observed); and that they simply would not survive life without their squishy pillow.

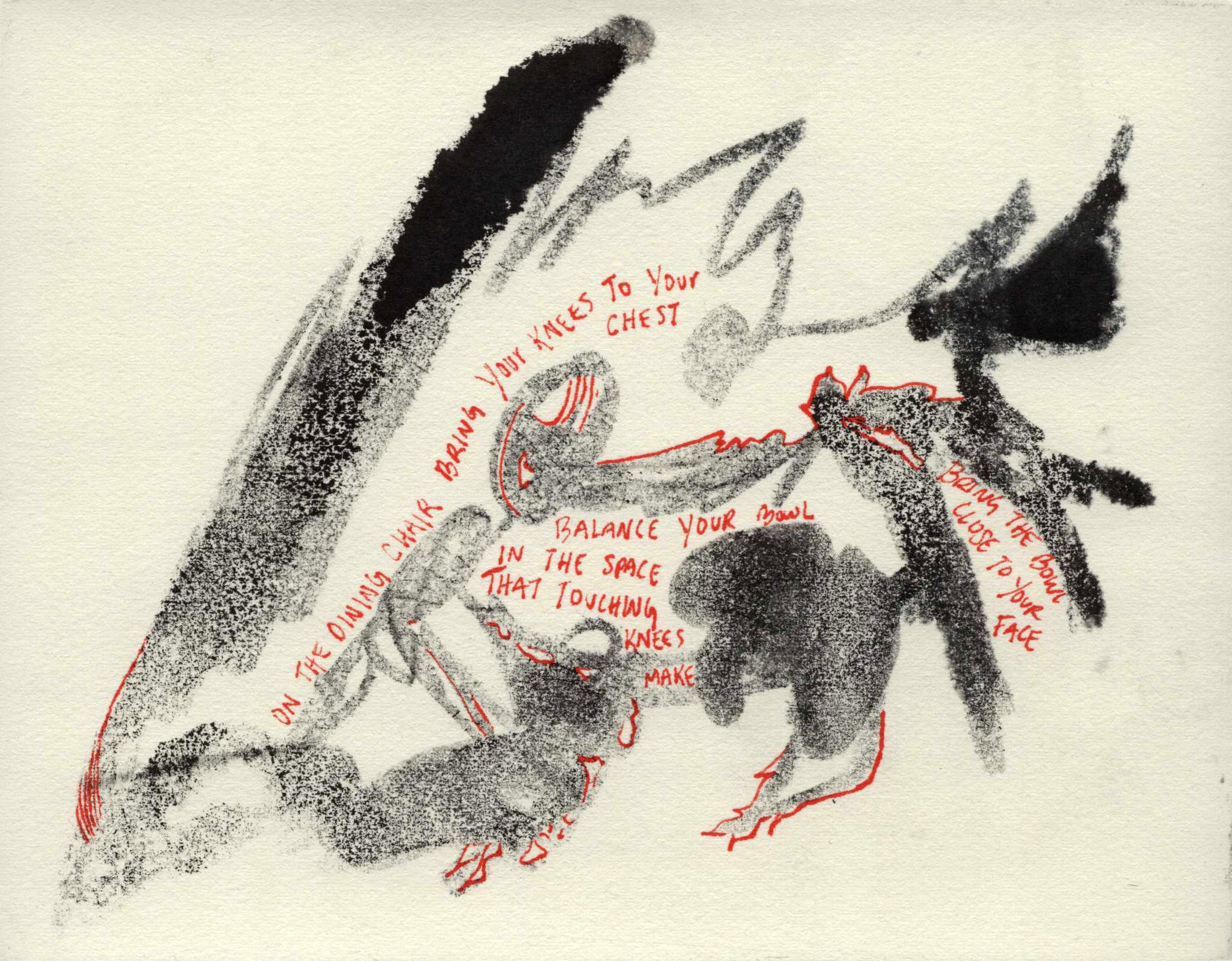

It occurred to me that I knew which pillow Meinzer was referring to. Selfies, a series of self-portraits drawn with charming crudeness on kitakata paper, depicts Meinzer swimming, stretching, and walking, among other poses. One print features Meziner hugging the squishy pillow to their chest. There is something relatable and honest about it — the bluntly drawn arms encircling the object, the familiarity and comfort of the embrace.

“With the subject matter, I just didn't want to think about it. I was like, ‘Oh, here's me today,’” Meinzer said. “Also, I’m really self obsessed. All the self portraits and the selfies are kind of a continuation of that self-ness, I would say.”

As a nonfiction writer, I was interested in this: the raw depiction of a self. I explained my own work in personal narrative, how I was beginning to tire of myself, the first person, and the “I”’s dotting the page. “It all feels vaguely narcissistic,” I said. Meinzer agreed with this; they also have concerns about self depiction. They spend a lot of time in front of the mirror. They’ve seen so many photos of themselves and drawn themselves in so many different ways that they’re no longer sure what their face looks like. Their fingers skim their cheek as they tell me this, as if to confirm their physical presence. “Looking at your image, you can become really disconnected with yourself,” they said. It’s a disconcerting experience similar to being in a room with multiple mirrors, where you’re forced to confront many reflections of yourself from all sides. Looking at yourself, I realized, is not necessarily synonymous to seeing yourself.

Meinzer investigates their perceived disconnect between mind and body through the 30 second process of printmaking, which was how the Selfies were made. Printmaking is Meinzer’s way to shake off their technical training in drawing and painting in favor of an “intuitive type of making,” which they find akin to muscle memory. “I want things that put me back in my body,” Meinzer, who described themself as anti-movement, explained. “I really have a hard time feeling like I'm living in my body. I feel like I spend a lot of time in my head. But I’m not going to think myself back into my body, I’m going to get myself back in by feeling something.”

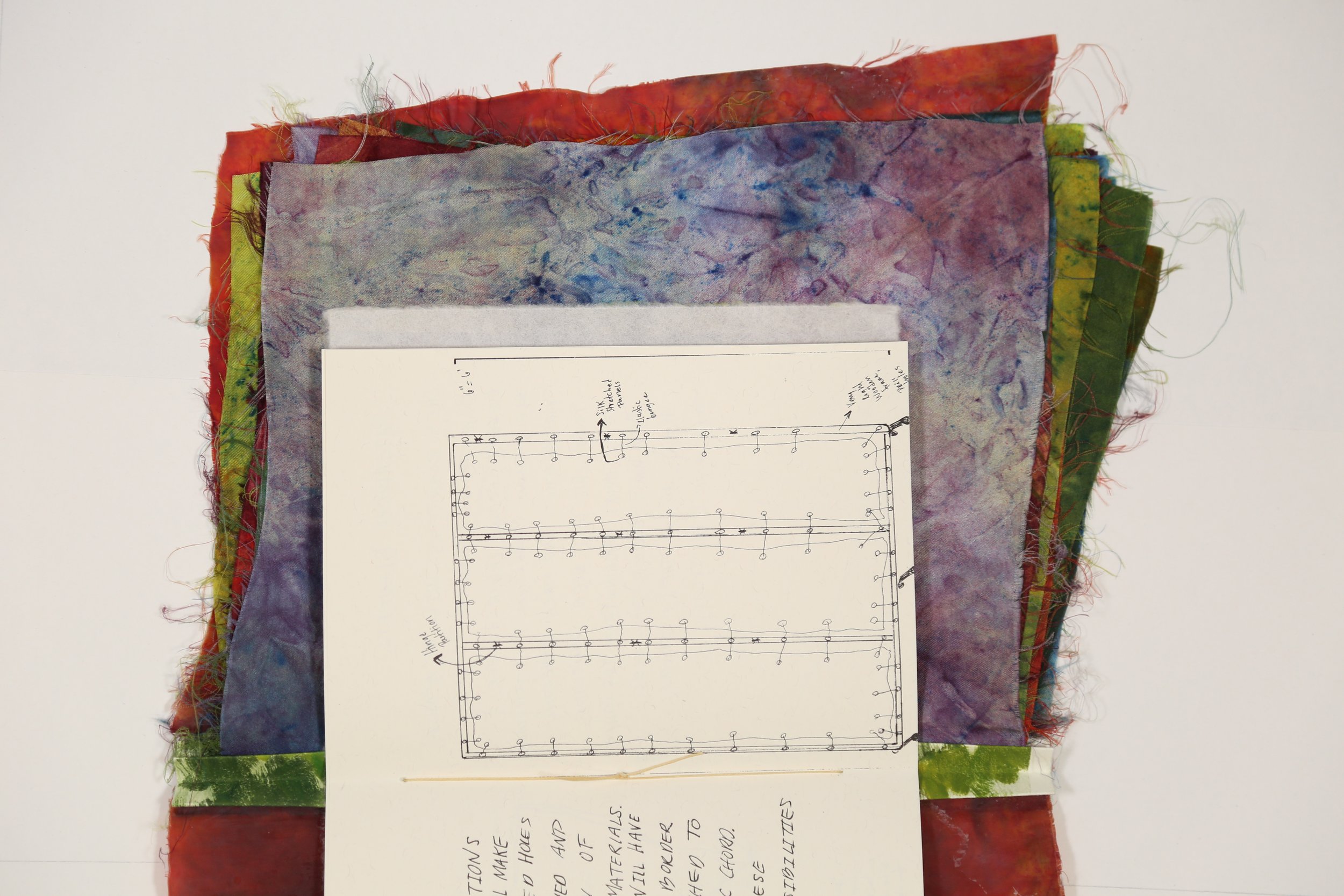

It’s important to Meinzer that audiences are grounded by the tactical element of their work, that they remember how to sit and interact and use things. Meinzer’s objects evoke a choreography of the body, urging users to consider the ways they traverse through space, and what they can touch and do. The objects are situated in an environment that can’t be “beige and millenial,” but possesses its own visual language.

Knees

This is apparent in The Dollhouse, which houses Meinzer’s alter egos, Baby Dyke and Lady Darling. The objects within the dollhouse, from the dolls to the furniture themselves, exist to facilitate play and conceptualize Meinzer’s past and present selves – allowing for a growth of consciousness. I press Meinzer on their definition of consciousness as something we continually attain throughout our lives. Do we become more distant from ourselves as we grow older? Part of me assumed, naively, that The Dollhouse was a nostalgic attempt to return to childhood.

Meinzer’s definition of play, however, is more intertwined with one’s submission to fantasy – sustaining the make believe. It’s something kids do all the time, Meinzer said: “If you’re playing a magical character, you’re not delusional. You’re submitting to fantasy. It’s how kids learn empathy. It’s a great tool for imagination. And we lose that in puberty when we become really aware of the gaze.” Slipping into a different self – a metamorphosis that occurs when you remove yourself from external perceptions of you – is something that fascinates Meinzer. It’s a phenomenon that happens with drag, BDSM, and within the trans community, they added. They view themselves as an amalgamation of many different selves and aggregate identities; in play, there is no awareness of fulfilling a role. The new, embodied self doesn’t necessarily imitate who you are in real life, but is unequivocally you.

The follow-up question naturally became, “Is there a way to teach people this?” I pulled up the first page of their portfolio, where they described themselves as “interested in crafting games.” Were games the best medium to activate the confrontation of self?

“I hate games,” Meinzer said bluntly.

“What?” I was incredulous; yet this, I soon discovered, would be my introduction to one of their many paradoxes.

“I'm not interested in games that are traditional, like a board game or a card game or something with a set objective, or way to win,” they explained. “And while I can see the merit and satisfaction in organizing yourself in relation to that sort of structure, I'm personally so bored by it. People get really defensive when I talk about this, especially board game lovers.”

I pointed out the window. “I think I see them coming,” I said. “They’re rallying on the walkway and they’re all holding Monopoly.”

“Yeah, if you’re [a board game lover] reading this, cool it,” Meinzer said.

One game Meinzer does enjoy, though, is arrangement. Their piece, Anti-Puzzle, debuted at Caffeine Underground in Bushwick, and features birch plywood puzzle pieces meant to be assembled on the printed wood table. There is no making Anti-Puzzle, no correct order it can be arranged. It also doesn’t reference anything – it doesn’t take on the elaborate shape of a duck, for example. Instead, how much of the game people can take into their own hands, and apply their own experience and intrigue to the rules, is Meziner’s metric for whether a piece was successful. They recalled the different approaches users took with Anti-Puzzle: some tried to arrange all the patterned pieces together, while others stacked them like blocks. “That was the best thing that happened, because I would have never thought to do that,” Meinzer said. “Other people had covered the table completely so that all of the holes were hidden. And they were like, ‘Oh, did we win the game?’ And I was like, ‘Sure, yeah.’”

Anti-Puzzle

Still, Meinzer recognizes that they actually are operating under a set of rules: their audiences are not puppets, and they aren’t the puppet master. “It’s such an artist’s ego thing,” they said. “Like, you really want control over everything. And then when you bring people into it, it’s hard.” To Meinzer, the difficulty of relational aesthetics, and the participatory element of their work, lies in the tension between knowing what to give and not giving too much. “I don’t want people to be used as a medium as opposed to just interacting with a piece,” they continued. “I am realizing how desperate I am for a very specific pattern of use. But then it's also like, I'm not interested in having wall text that says, ‘You can use this.’ That sucks.”

The variability of setting comes up here; would a gallery be the best environment for Meinzer’s pieces? Would they kill the casualness of the objects? These are questions Meinzer is still trying to figure out. They launch into another paradox: how their intuitive side of making is constantly wrestling with their intense planning side. Because their objects are meant for use, the piece needs to be referent enough to everyday objects, and not abstract to the point where the purpose of picking it up and interacting with it is completely lost. Even if there are certain rules in place, concedes Meinzer, they’re “definitely trying to really obscure the set of rules.”

With Anti–Puzzle, a game’s structure can and should be constructed by the user, whose agency depends on decision-making. When does the game start and finish? What are the rules of the game? These are questions the piece asks of the audience, meant to spur the activation of bodily awareness and co-creation on the users’ part. “The game can even be changed halfway through,” Meinzer added. “If you’re bad at the game you’re currently playing, you can definitely change the rules.”

To eliminate the performativity of the gallery space, Meinzer posited whether the best way to interact with their objects is in a room alone, without the acute awareness that others are watching you use the piece. I argued against this, because part of Anti-Puzzle’s appeal to me was its ability to form community, the way strangers were drawn together, even if briefly, to work on the tessellation together.

Meinzer shrugged. Maybe it’s a problem that doesn’t need to be solved. Ambiguity can be desirable. “If the piece fails, it says something about the space around us, the social rules that are assigned to that certain space,” Meinzer said. “Your pieces are smarter than you and they should teach you. You don’t need to know 1000% what your piece is doing.”

A new concept Meinzer is working on now involves unlocking a new level of bodily agency in the audience by encouraging the destruction of their artwork. It’s a pushback against their observed preciousness with art objects in the art world – “do they need to be treated that preciously?” They brought up Ray Johnson’s mail art, in which cheap pieces of paper are streaked with crayola marks, chafed by the mailbox, and carry the indentations of the hands that have held, opened, and transported the material. These signs of wear inspire Meinzer deeply. . There’s something beautiful about imperfection: the undeniable affectation of time and flesh.

“[With Anti-Puzzle], people were putting their iced coffee down, and it was condensating on the table,” Meinzer said, following our dialogue on signs of use. “Thankfully, or I don’t know, not thankfully, there were no marks left, but had there been a mark left, I realize I kind of would have been excited by that.”

This nonchalant approach doesn’t mean that Meinzer isn’t protective of their objects. They recalled a time their friend almost damaged the Anti-Puzzle, which freaked them out. It was another paradox they were grappling with: how open were they really to a piece being altered? When I explained my reaction to “For When You Want to be Alone” as a shelter, they countered by saying many had the opposite reaction – they found the environment hostile. To a certain extent, this accomplishes the goal of their work: “I want people to feel some sense of discomfort but also feel very safe,” Meinzer said. “It can’t just be this sanctuary safe space sort of thing. I’m trying to find ways to include risk or destruction or violence into the work…[to incorporate] some sort of decision making or risk within.”

Overall, though, Meinzer thinks art shouldn’t take itself too seriously. “That’s a huge thing for me,” they said. “Let’s all get off the high horse… it’s completely fine to make a drawing about a squishy pillow.” I remembered a quote I’d recently read, from painter and sculptor Georg Baselitz’s interview on The Talks magazine, on the struggle of artistic expression and why it’s essential: “The misery of the world has to express itself in the mind of the artist in the form of art — only ever the misery, never anything positive,” Baselitz said. Good things, he believed, would never cause audiences to look.

Meinzer scoffed at that. “I definitely don’t hold onto the idea that you really have to suffer for your art,” they said. “How crudely the Selfies are drawn reflect back to the fact that they are making fun of themselves. Baby Dyke was me completely making fun of my own naivety…but also accepting myself in a sort of quintessential queer coming of age. Baby Dyke and Lady Darling… they’re a complete spectacle. They’re in their world being ridiculous and dramatic, and that’s great.”

Meinzer isn’t as concerned about giving pretext for their work, or the biographical elements that inspired them to make the piece. These facts naturally come out through the piece; the open-ended nature of interpretation, and the possibility of an unexpected reaction, is more interesting to Meinzer. They aren’t as fixated on what’s authentic and what’s a construct, or having art serve as an emotional compartmentalizer in their “dust bunny” of a brain. Baby Dyke and Lady Darling are just hanging out, they said. The piece isn’t about when they’re going to grow up. It isn’t about having two genders. It’s about the intentionality and paradox of having two separate beings in one body that complement each other.

“What would you say is the purpose of these objects, then?” I asked.

Meinzer replied, simply, “They help me understand myself.”