Feature by Susana Crane Ruge

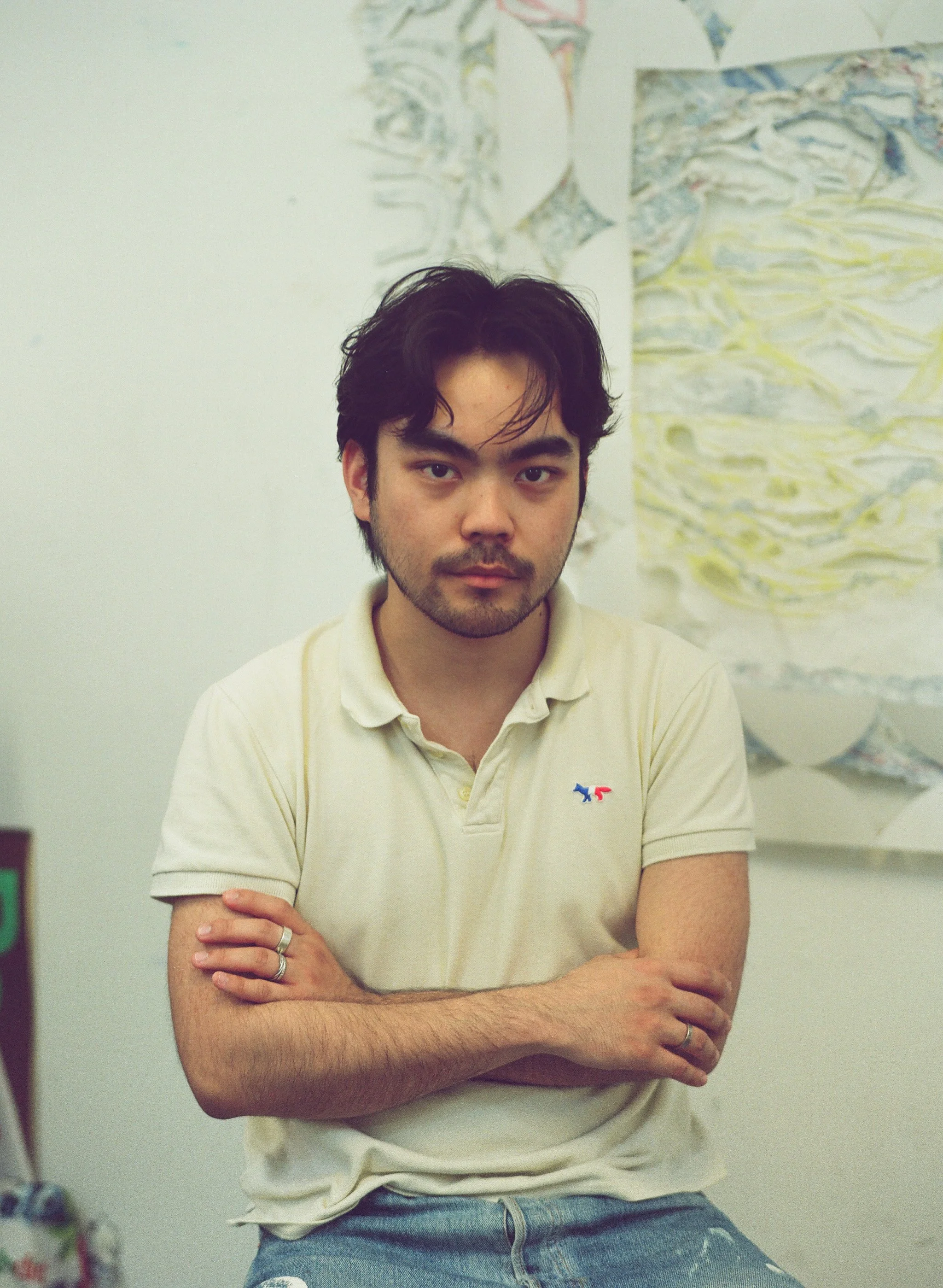

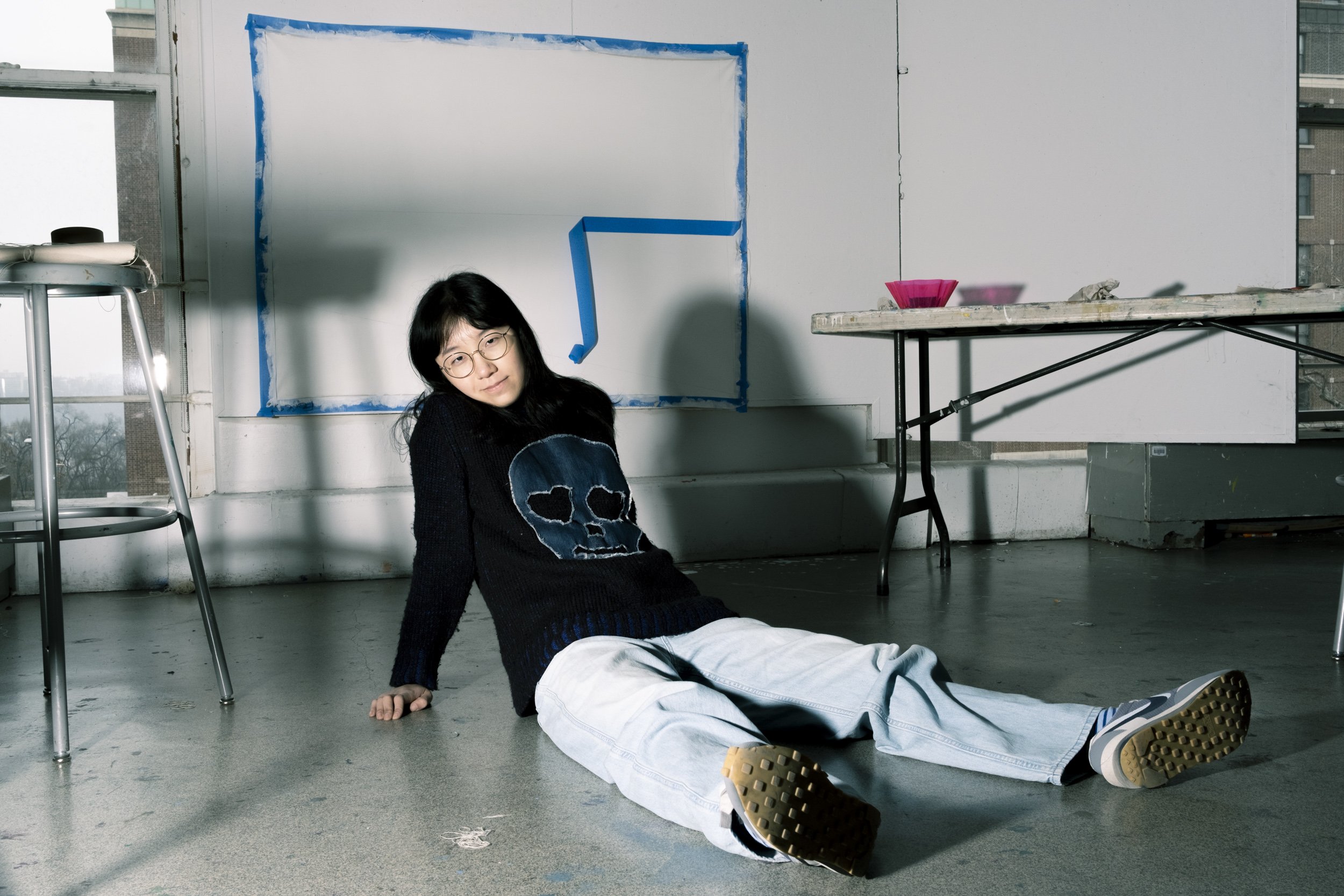

Photos by Emily Lord

Forest Wong is a Junior at Columbia College studying Visual Arts, who works mostly with charcoal, graphite, oils, and chalk pastels. She has been creating art since she was a child. Forest is her given name, chosen before her mother knew the baby’s gender. Forest thinks that is pretty cool. In her interview, she discussed her approach to art, her malleability as an artist, her family, and AI generated art. At the end of the interview, we realized we had forgotten to order coffee.

C: First, tell me a bit about yourself as an artist.

FW: Growing up, I've mostly drawn with charcoal, graphite, and chalk pastel. I stuck to those chalky substances because I really liked how they moved, and how I could really mess with and play around with them. Now, I've been working with oil, since I also like how it moves on the canvas. I am interested in manipulating, exploring it. Also, I have always admired people who used oil. Growing up, I would watch my grandpa and my mom paint, which encouraged me to make art. Transitioning into oil has been an extension of that.

SC: How has your relationship to your family affected you as an artist?

FW: I come from a very artistic household, so it always felt natural to start doing art. I saw so many artistic creations I wanted to emulate, made by people I look up to, so I began exploring, and now here I am. The same happened with music. My mom and brother play the piano; I would see them and think, "I'll click around on the keys, too."

SC: Could you tell me more about the piece with your family portraits?

FW: While making that, I wanted to have fun playing with different materials. The materials I had were the same things that would be lying around my home. A Yakult bottle, grass jelly, stuff like that. Since I was feeling really homesick last spring, I wanted to incorporate my family in my work by tying in their portraits, and implementing other themes with things you might find around a Chinese house specifically.

SC: Was this piece specific to certain family customs?

FW: Yeah, those types of rituals I never really thought about growing up, but now that I'm not physically there with them, I see their value differently. I thought about it and it's another way to get closer with my family, having that memory of them.

SC: Could you tell me about your affinity to making textured, unblended, and visible strokes?

FW: The act of painting and drawing is so magical, right? Because when you look at a finished painting, you're just wowed by it, like, “Huh, wow, someone was able to produce this.” There's something about showing the process in the physical marks themselves that is interesting to me. A painting is just a collection of marks on a surface. That's what I'm interested in. Chalk and oil give me that plasticity and malleability, they're so versatile. The marks depend on the thickness of the stroke, the speed of it—each mark conveys a lot, they capture the gesture of the hand, too. You get to see the process of it.

SC: Is making visible strokes a technical or emotional choice for you?

FW: Both, I think. I like to be very careful not to let the strokes get lost in what I'm doing, because my goal is to show the audience the process I went through. I like guiding their eyes and having the painting be a visible creation, not just an end goal.

I hate feeling like I overworked a painting, and I've done it so many times. If you overwork the painting it's the most tragic thing, because the process of making it is so beautiful and so fun. Sometimes after a few hours or days I look back at it and think, “Oh god, I killed it.” Showing the raw process is the most satisfying relationship with your past because you get to see what you did and how it was done.

SC: How have you changed your approach to art?

FW: When you're first learning and trying to pick up as much as you can, you just draw what you see. Initially, I would only work with references. And I still do, in some ways, but now I'm paying attention to the design, the message, to the parts that are important to me. If I'm looking at my portraits as just portraits, they don't have another meaning to them. But in the portraits I make now, I'm paying a lot more attention to where I want to lead people's eyes based on contrast, value, and color. Before, I was purely into representation. I just wanted to get it to look like the thing I was looking at— transferring this to this, like in photo realism, or just photography. I just wanted it to look accurate, but now I'm trying to be more loose with it, trying to direct it. I don't just copy, I get inspired by what I see.

SC: And how would you define your relationship with your past work?

FW: I definitely like some of it, but other pieces make me cringe. Especially the work that I did two years ago. I don't want to look at it because I've changed so much since being at Columbia, learning, and growing up. I just don't want to touch it, you know?

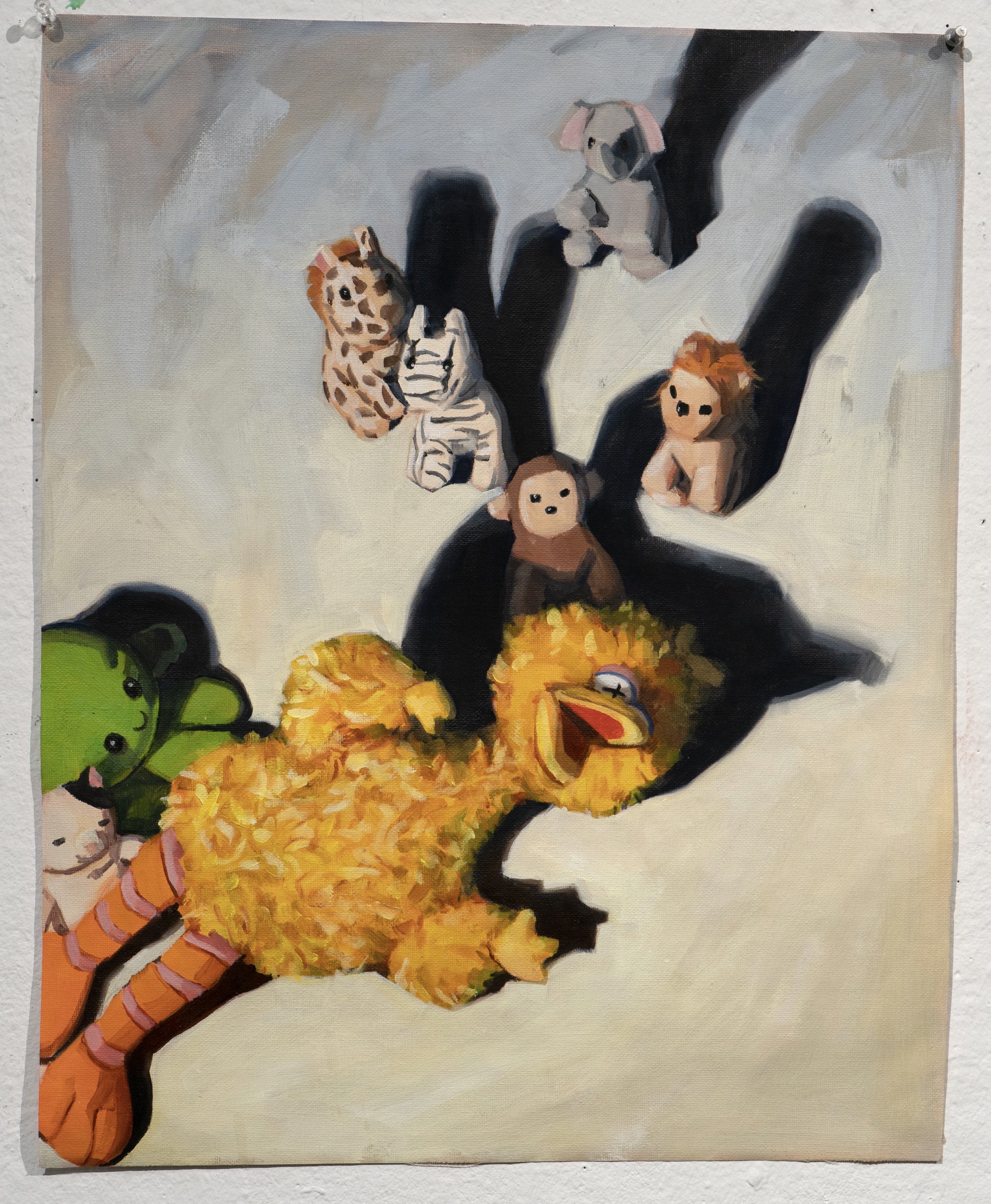

SC: I know you mentioned you like high contrast painting, like the Tumbling series and the stuffed animal piece, could you tell me more about that? Are you incorporating that technique in more of your work?

FW: Actually, this is something I'm trying to continue with in the work I'm doing now—this high contrast, striking look—because I'm really interested in shadows and their shape. This ties back to what I said about not going full into representation and having the marks and the physical process in the piece. Shadows help me lead people's eyes.

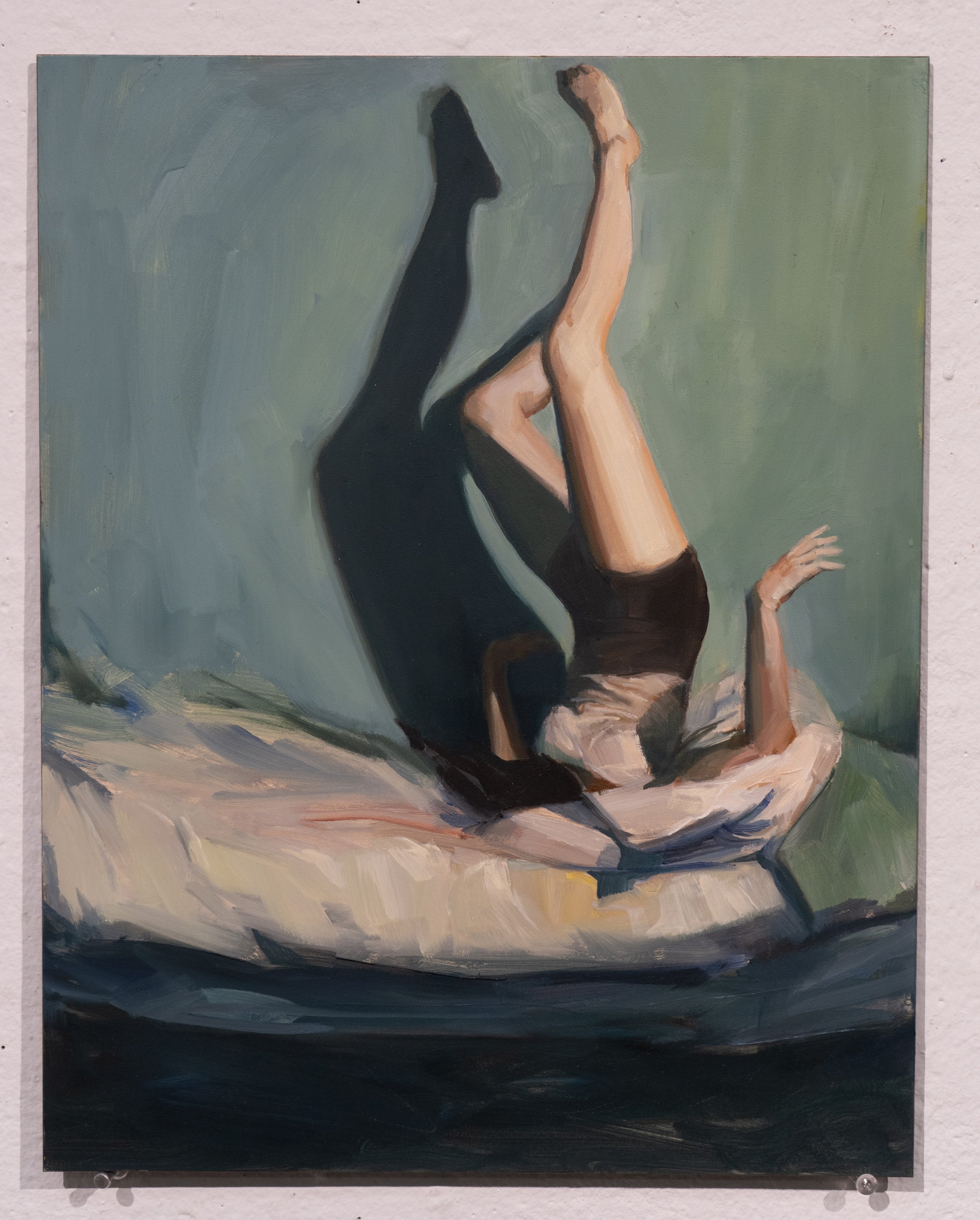

SC: In your piece, “Because I see you as a body sees itself within a mirror,” you have a really cool division of reality and non-reality, it makes you look again. What was the process of making it?

FW: So, okay, I hate naming my artwork. If I could just leave all my artwork Untitled, I'd be fine with that. But with that one, I got the title from a movie, Ghosts in the Shell, a 1995 anime that deals with this dystopian, futuristic world where people and machines are intertwined in a really dark way; so the movie deals with humanity and what it means– my human-ness, like my human ghost. So I started thinking about what the value of human art even is, if there is a difference from AI generated stuff, so that was the question that I was asking with that painting. And I even used digital stuff to make the reference for the project, so that was cool.

I was trying to convey the physicality of being human through the tension of the figure. In the clothes you could see her stretching it and the hands are clenched, the feet are clenched, I'm trying to convey that anxiety. When you see the figure you see how tense she is and you can feel it in your own body too. I want to mimic that feeling, right? Anyway, that's what I was trying to accomplish with that pose. And with the mirror itself, I'm bringing it back to ghosts in the shell, like the ghost of a person, like the humanity of the person, what value it has. I know, it's really depressing.

Because I see you as a body sees itself within a mirror

SC: How have you coped with that?

FW: I'm trying to develop that shift in my ongoing work. I actually have another reference that I'm working on with photoshop and digital stuff. I mean, there's no way to really stop the AI train, right? But I'm just going to incorporate more digital stuff into my work; I think that's the way to go.

SC: How do you see yourself continuing your work?

FW: Mixing digital with traditional. I'm actually going way more into digital. I got into Photoshop last summer and I thought, oh my gosh, wow, look at this new medium, I have to explore it. It refreshed something in my way of thinking about art and gave me so much freedom to make mistakes and focus on other details when creating.

SC: Talking about AI, how do you think that art exists as digital vs. physical?

FW: You can't really bring the digital into the physical world completely. That's why I haven't completely abandoned it. But being able to experiment with digital stuff, not having any boundaries, it just opened the doors towards so many different possibilities. This eternal anxiety and fear ended up doing me good.

Forest and I walked back together to campus, where she had to get to the studio to work on some pieces and I had to catch up on some readings. The sunset permeated the sky on 114th street and, an hour and a half later, the conversation was done. To see more of Forest’s work, her instagram is @forestwongart.