Feature by Mara Toma

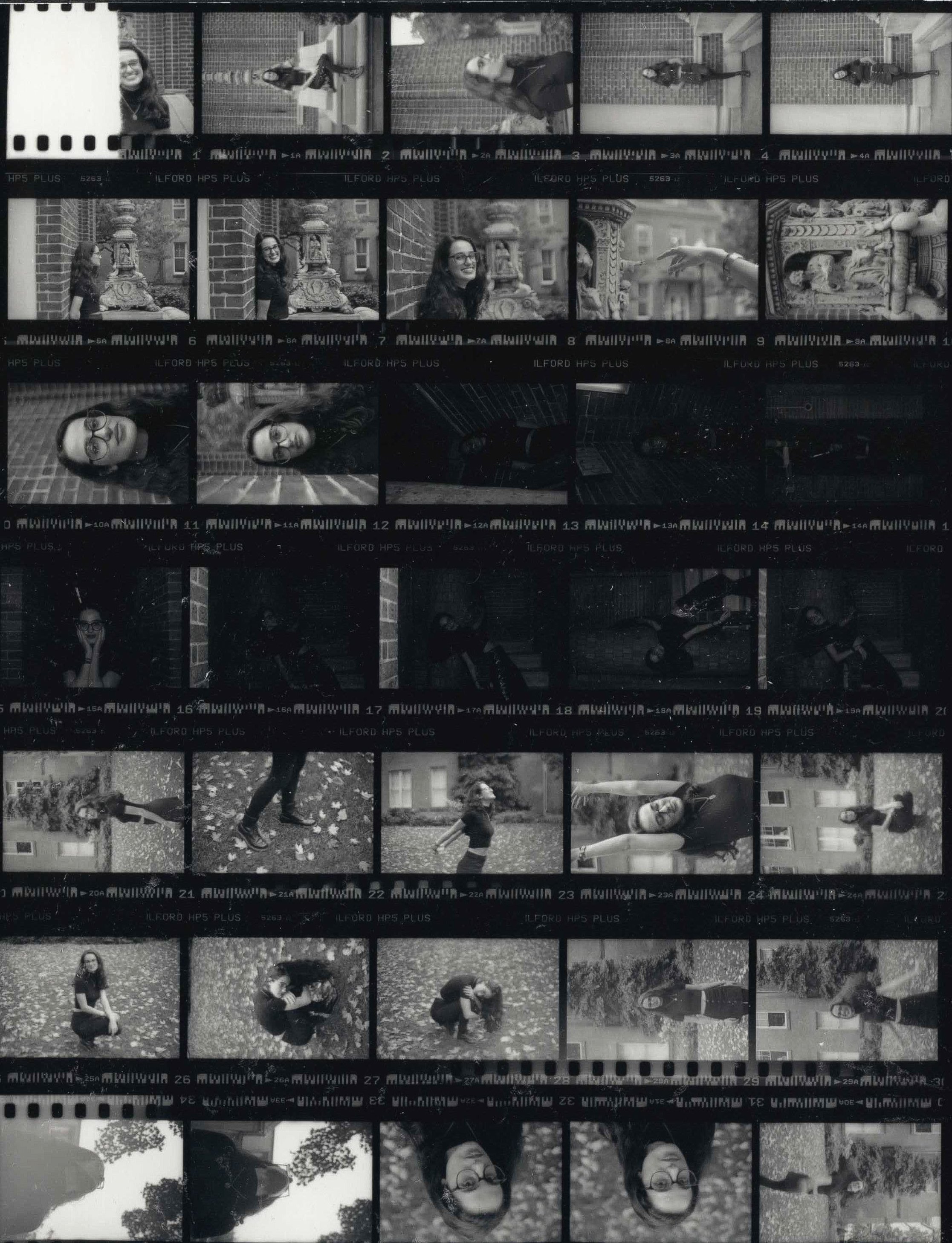

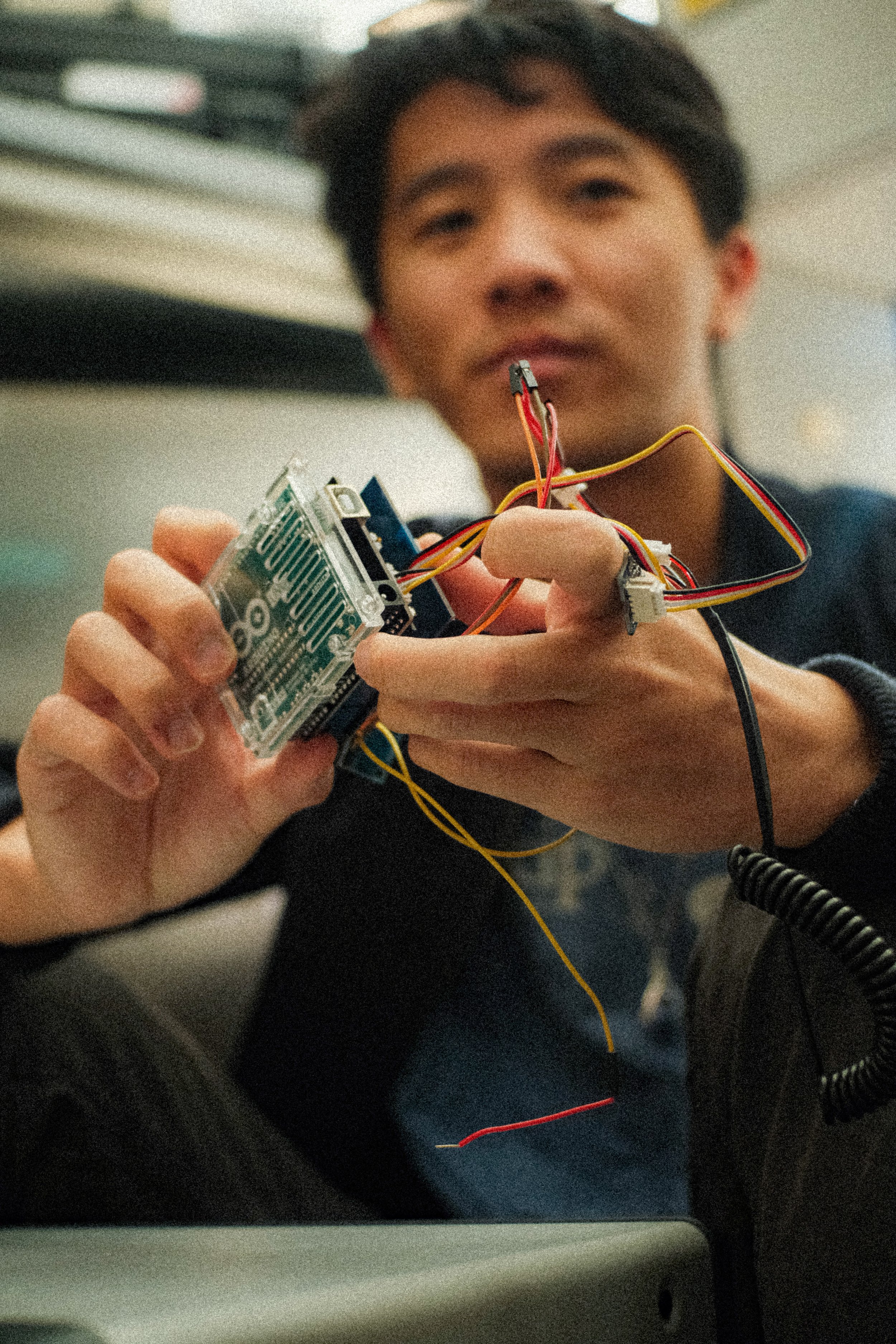

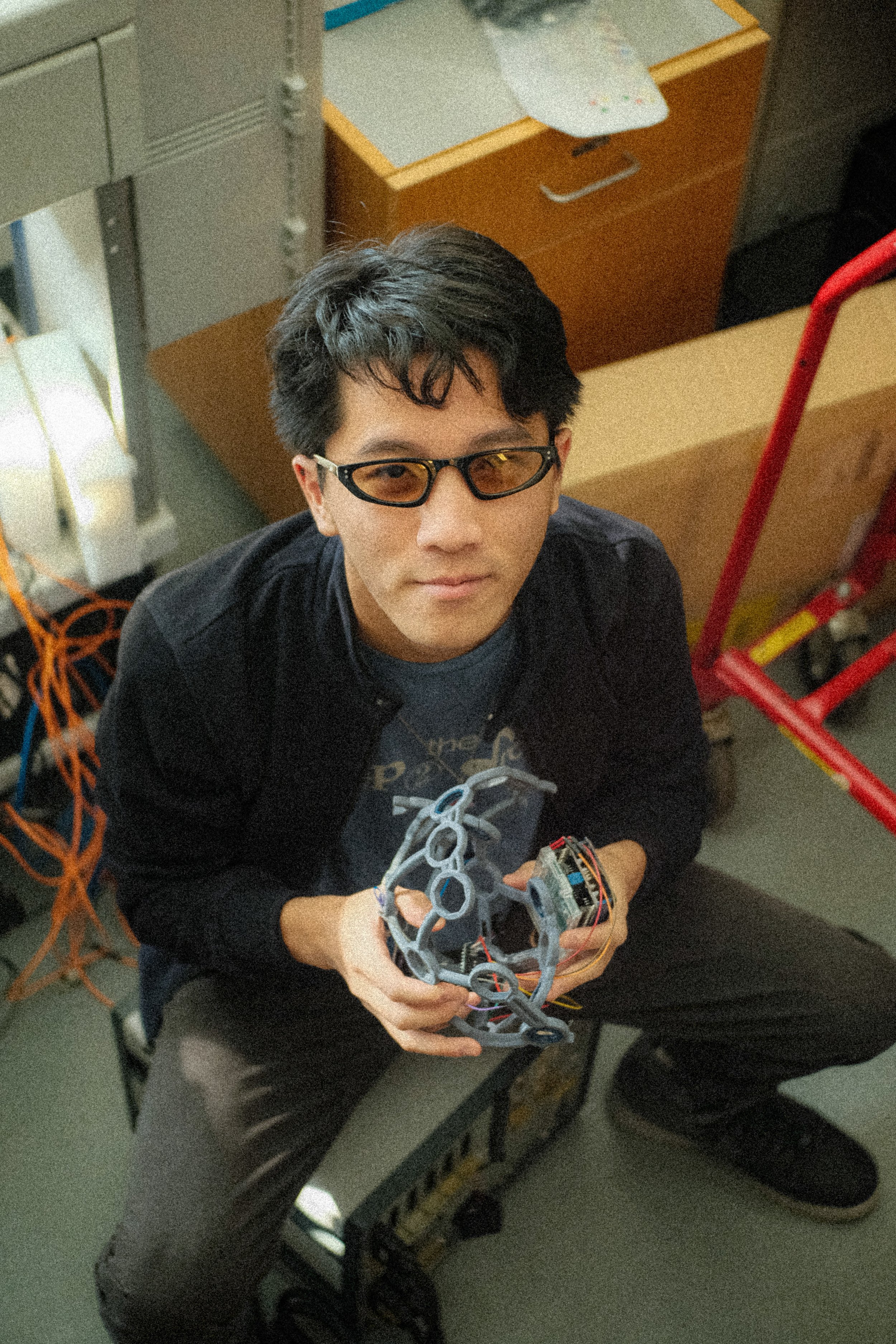

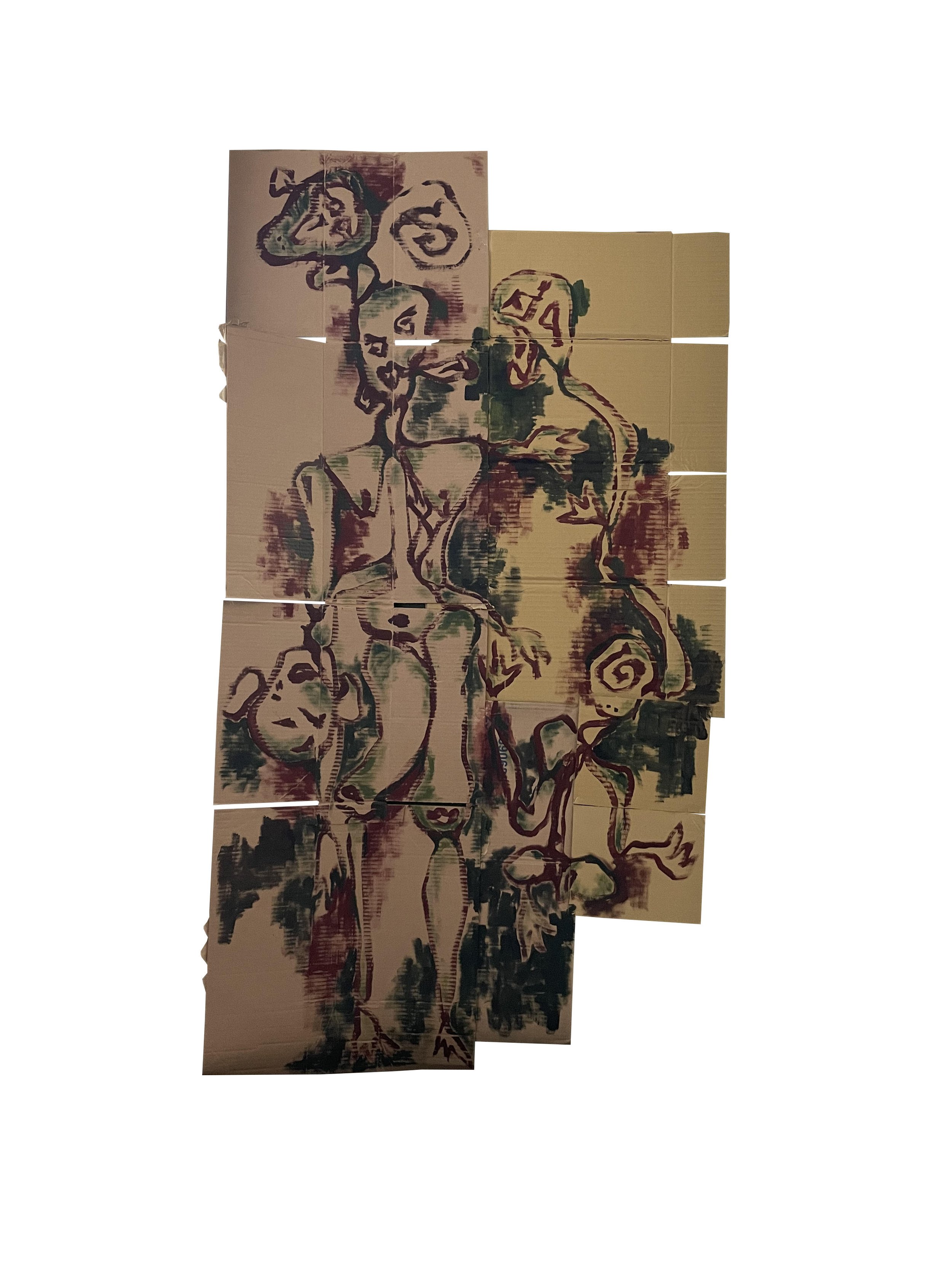

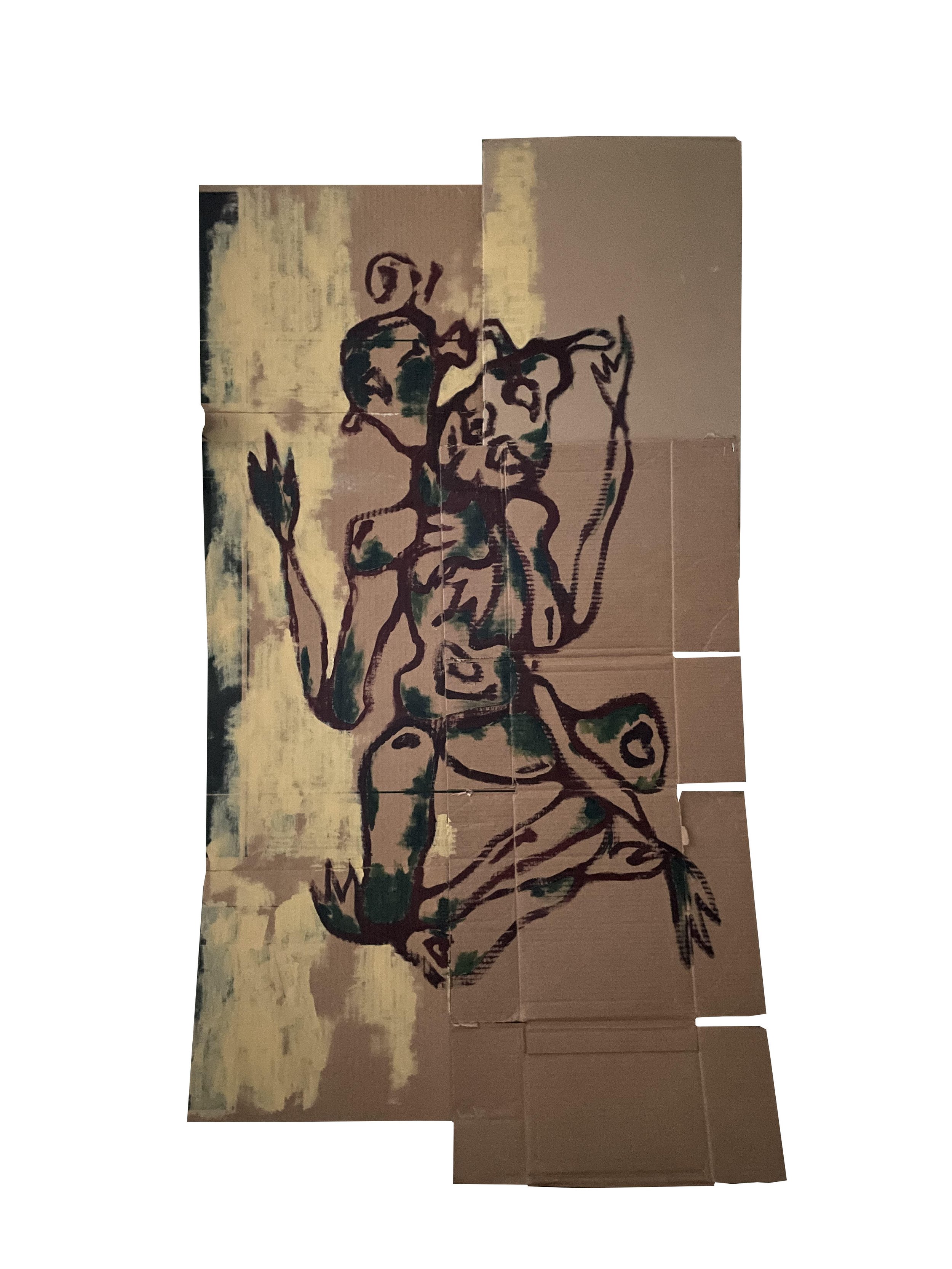

Photos by Wynona Barua

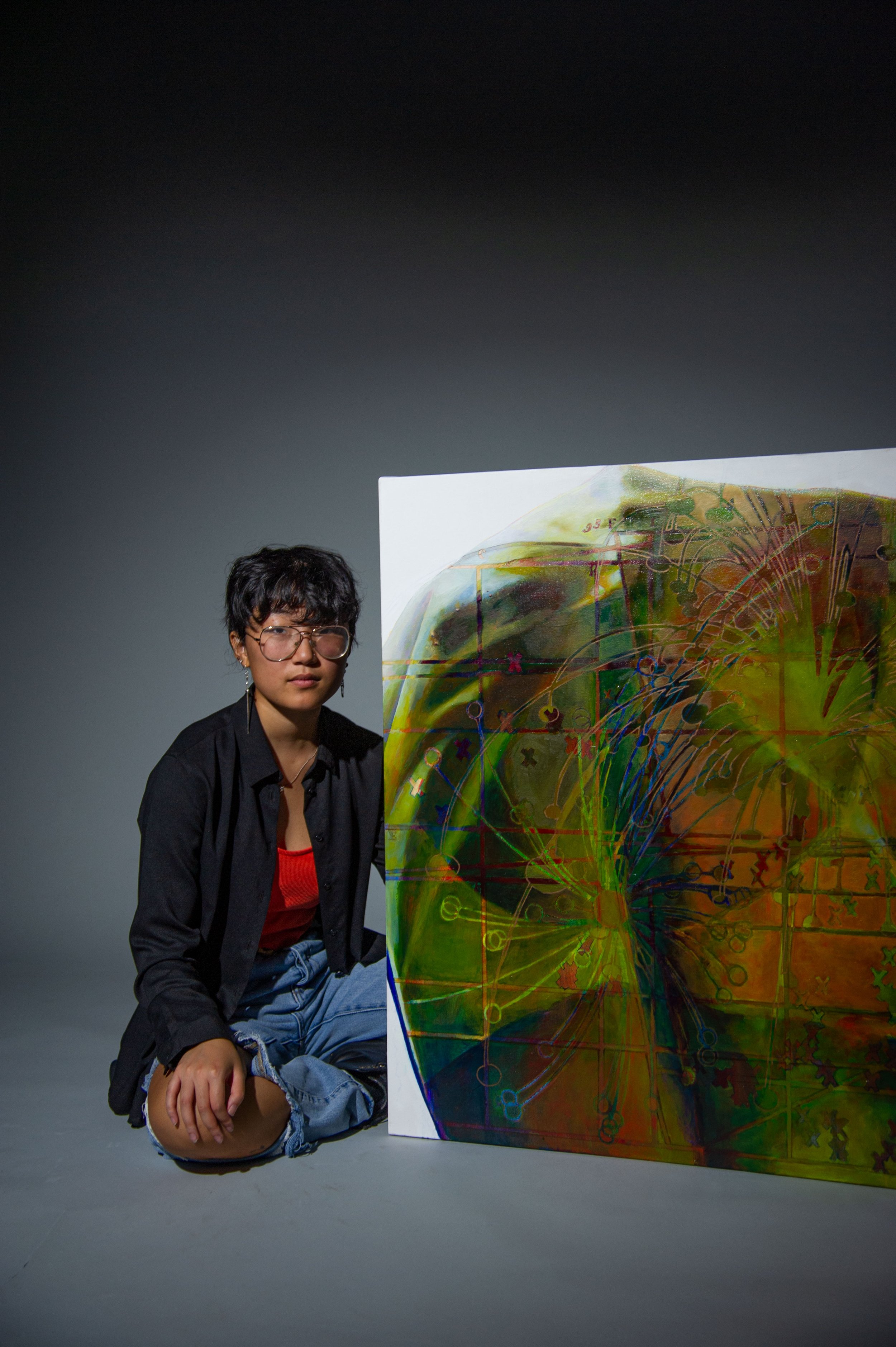

Pranavi Khaitan (she/her) is a sophomore at Barnard College studying Urban Studies and Economics. Originally from New Delhi, India, her photographs explore the distinct and complex relationship between people and their surroundings. Photography is a way in which she defines and redefines spaces while also exercising gratitude and awareness towards the intrinsic characteristics of each lived experience. Her photography is a powerful reminder of how we each experience and process ordinary encounters in distinct ways.

Mara Toma – What got you into photography?

Pranavi Khaitan– I started off with photography at quite a young age. I got a DSLR camera as a birthday gift and it turned into a passion of mine. It began by photographing national parks in India: mainly birds and wildlife. My father loves the environment of national parks, so my family would go on a trip every New Year. I would take out my dusty camera and take a few pictures. When I was looking through the camera, I processed the world differently. It gave me a sense of wonder to look at the world around me and see what’s going on– sometimes it could be as simple as seeing fishermen through nets in a coastal town in India.

MT– You mentioned that you link the act of photography with the act of noticing. How does noticing play into your work?

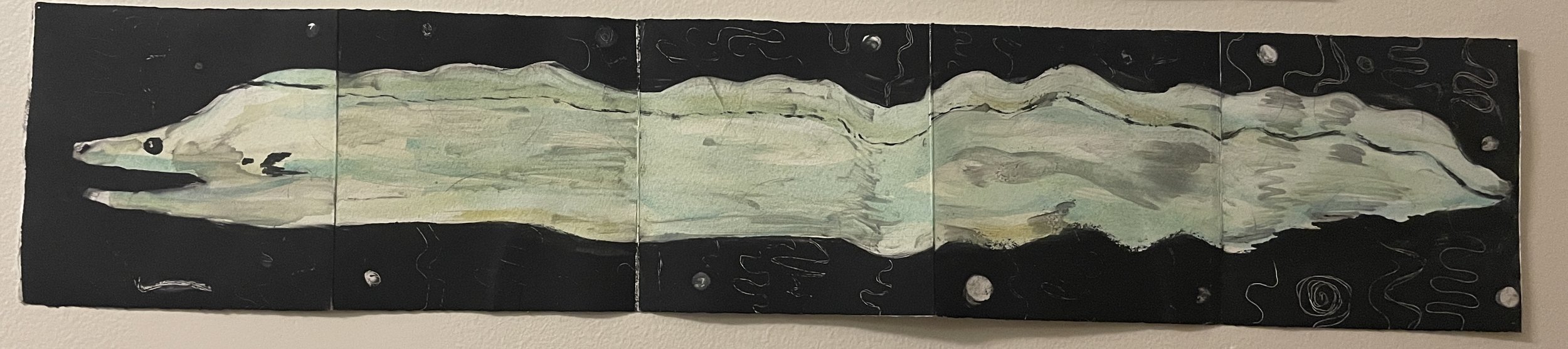

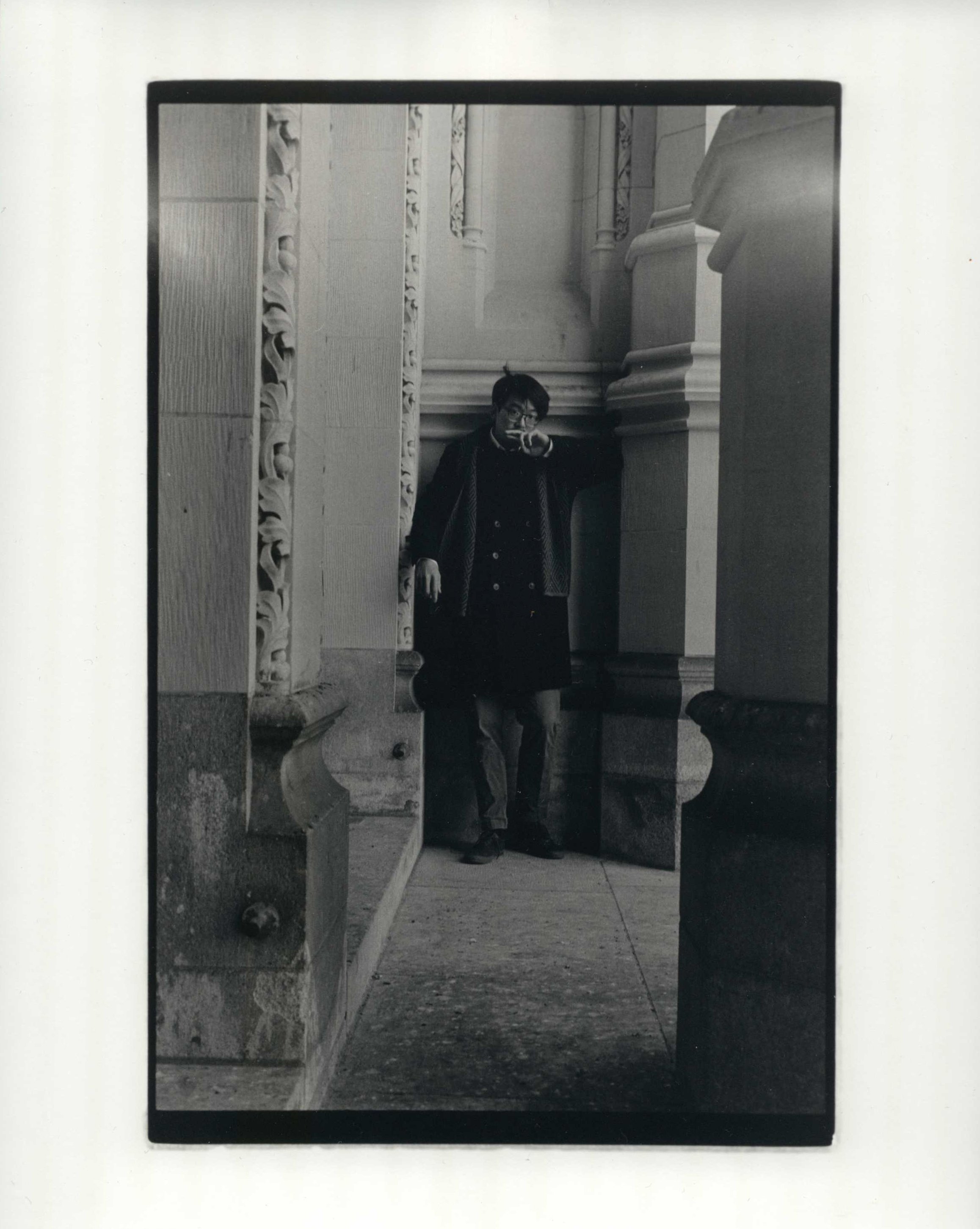

PK– For me, freezing that moment or noticing a specific part of that moment evokes newness, uniqueness, and the ability to highlight the extraordinary. I deeply enjoy looking at the world this way. It's refreshing. My photography evolves as my interests change. For example, I had a period when I was very interested in Mughal history… I realized that the city I was living in was a hub for Mughal architecture. When you live in Delhi, you drive past these monuments every day. It’s the idea of reminding people that this exists. That's where I'm coming from: being able to show that daily life does not have to be mundane, it can incite excitement and wonder.

MT– You described photography in relation to your own shifting sense of self. Do you think you are trying to immortalize moments or bits of a changing personal and collective landscape?

PK– I am not trying to immortalize anything. My work highlights that places change, people change, things are moving, and things are happening around me. I aim to embrace change and understand the environment around me. It’s about highlighting my perspective which changes as time passes. One moment I could be focusing on monuments in Delhi: to highlight the role that this part of history played in shaping my city and the art in all its beauty. Another moment could be trying to understand my peers. I had a point where I was just taking pictures of things that were happening in my school. I think that my practice developed a lot as I grew and saw how I could use photography to display my perspective. I don't think I'm trying to highlight anything specifically— but that’s also the beauty of it.

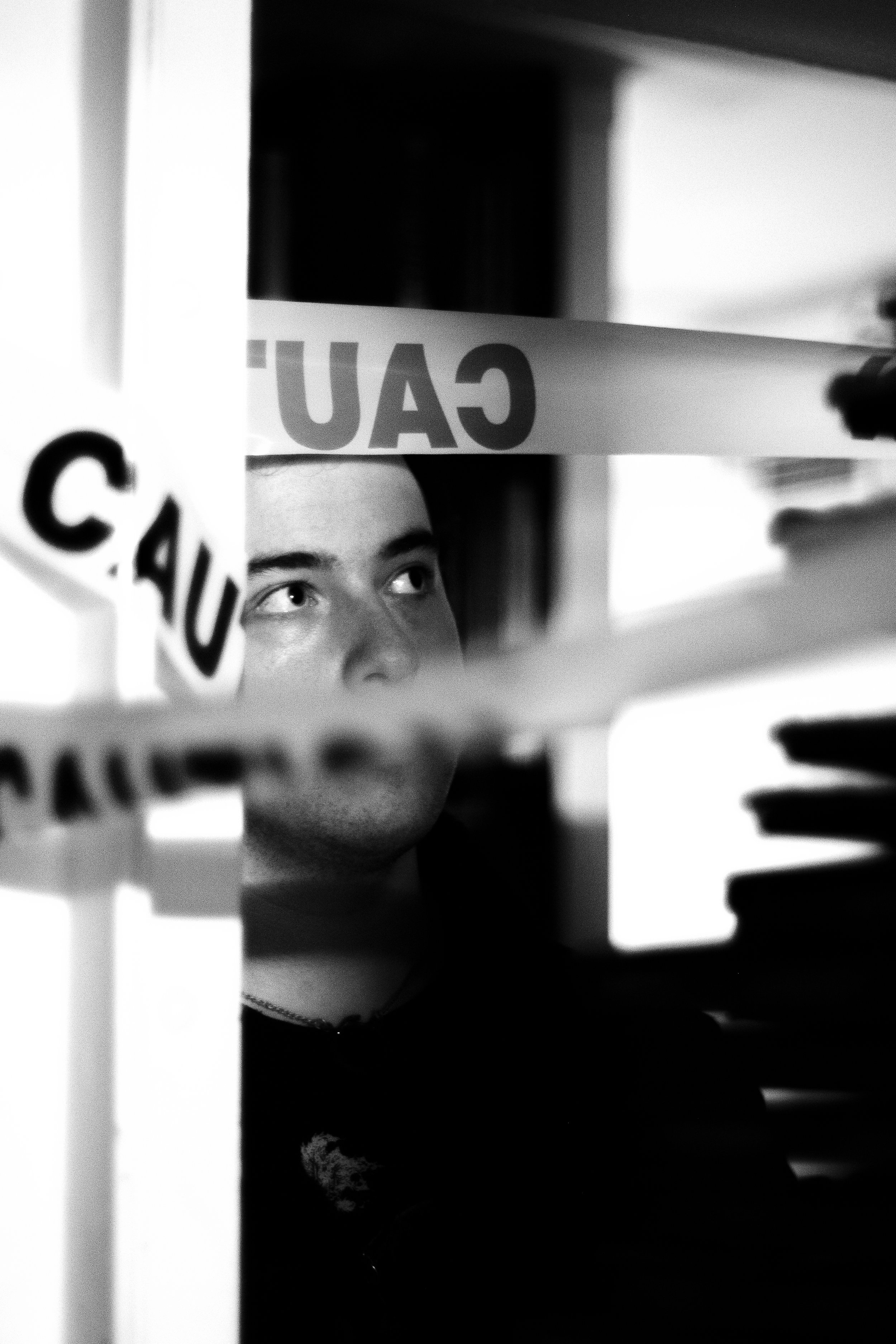

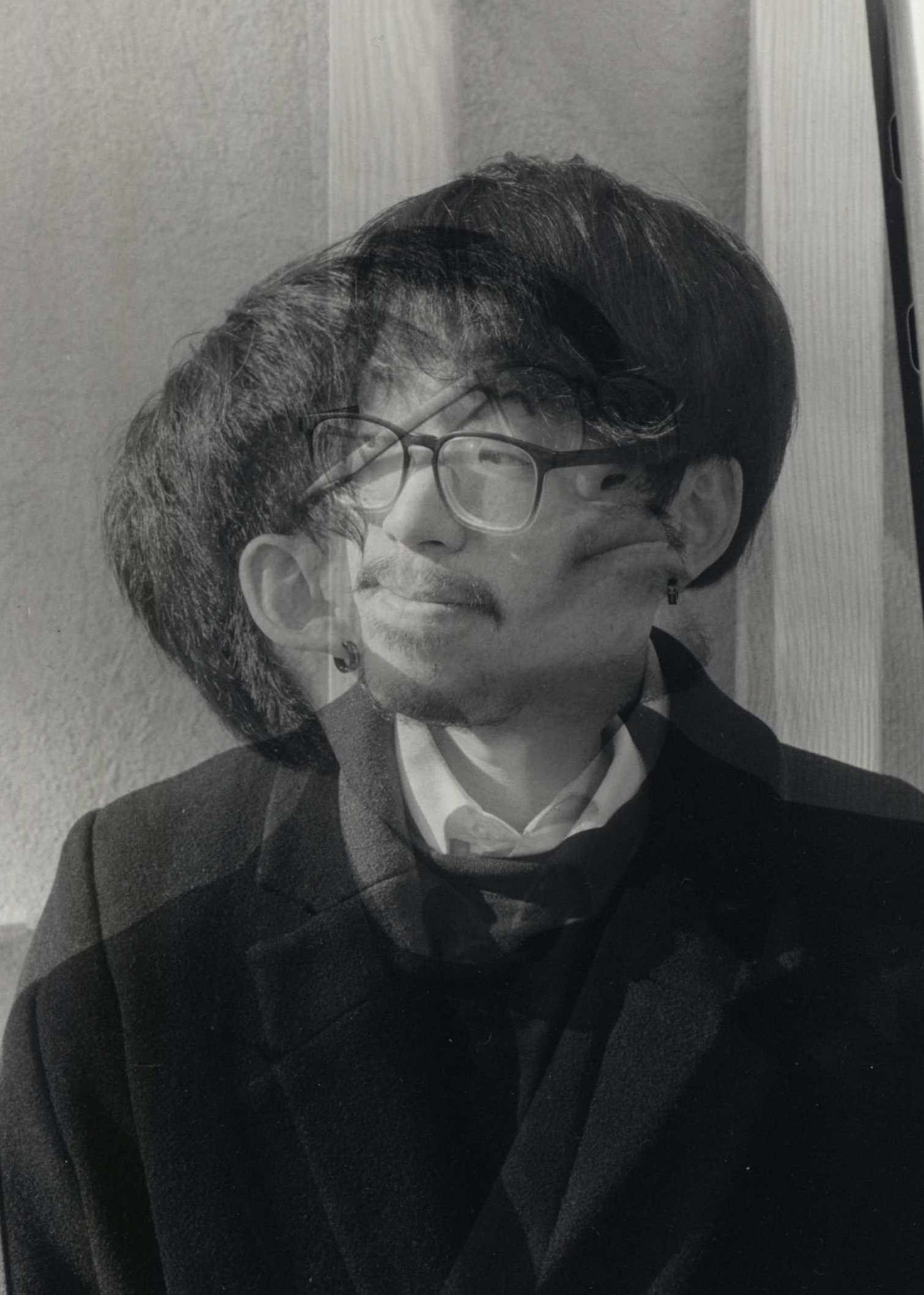

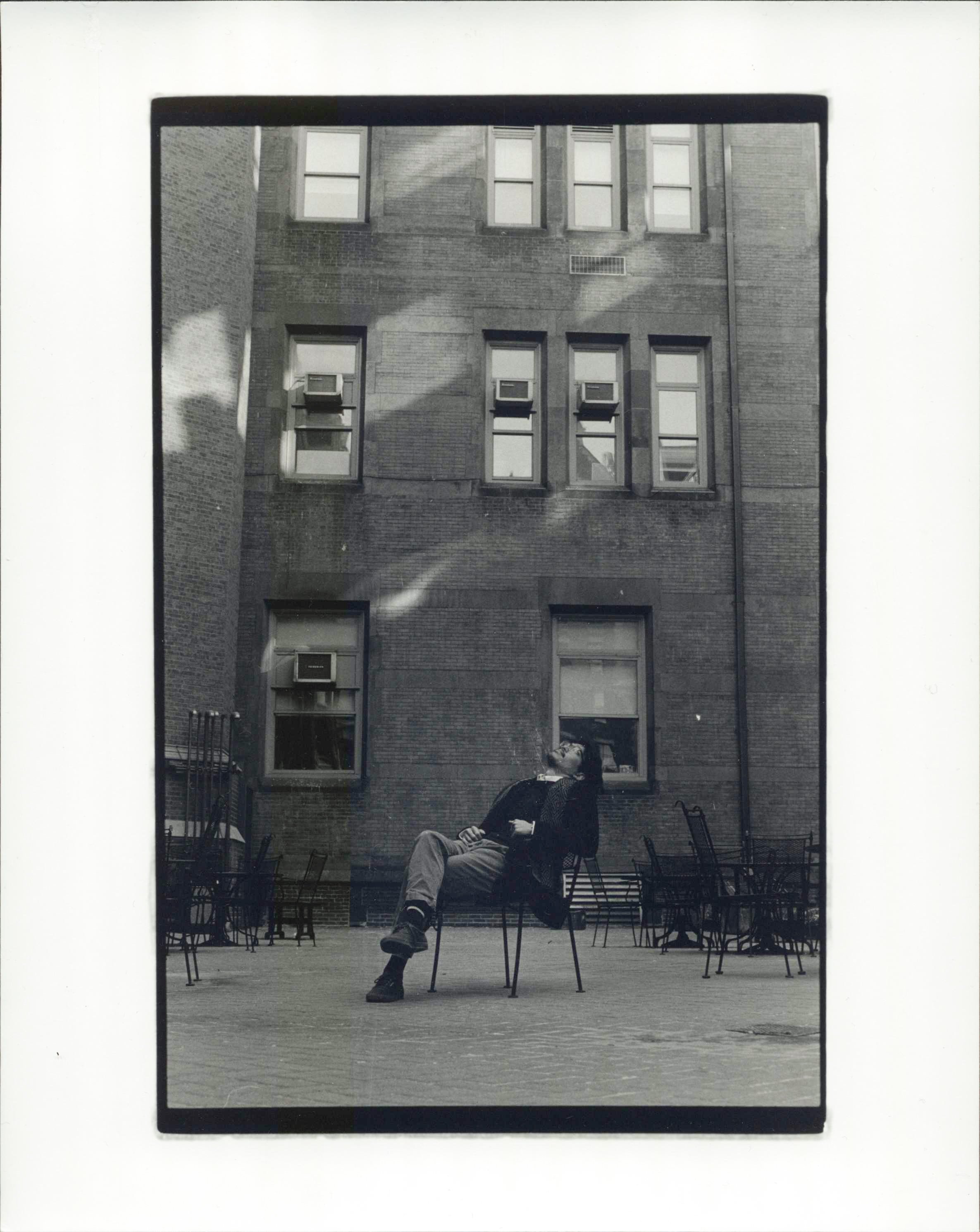

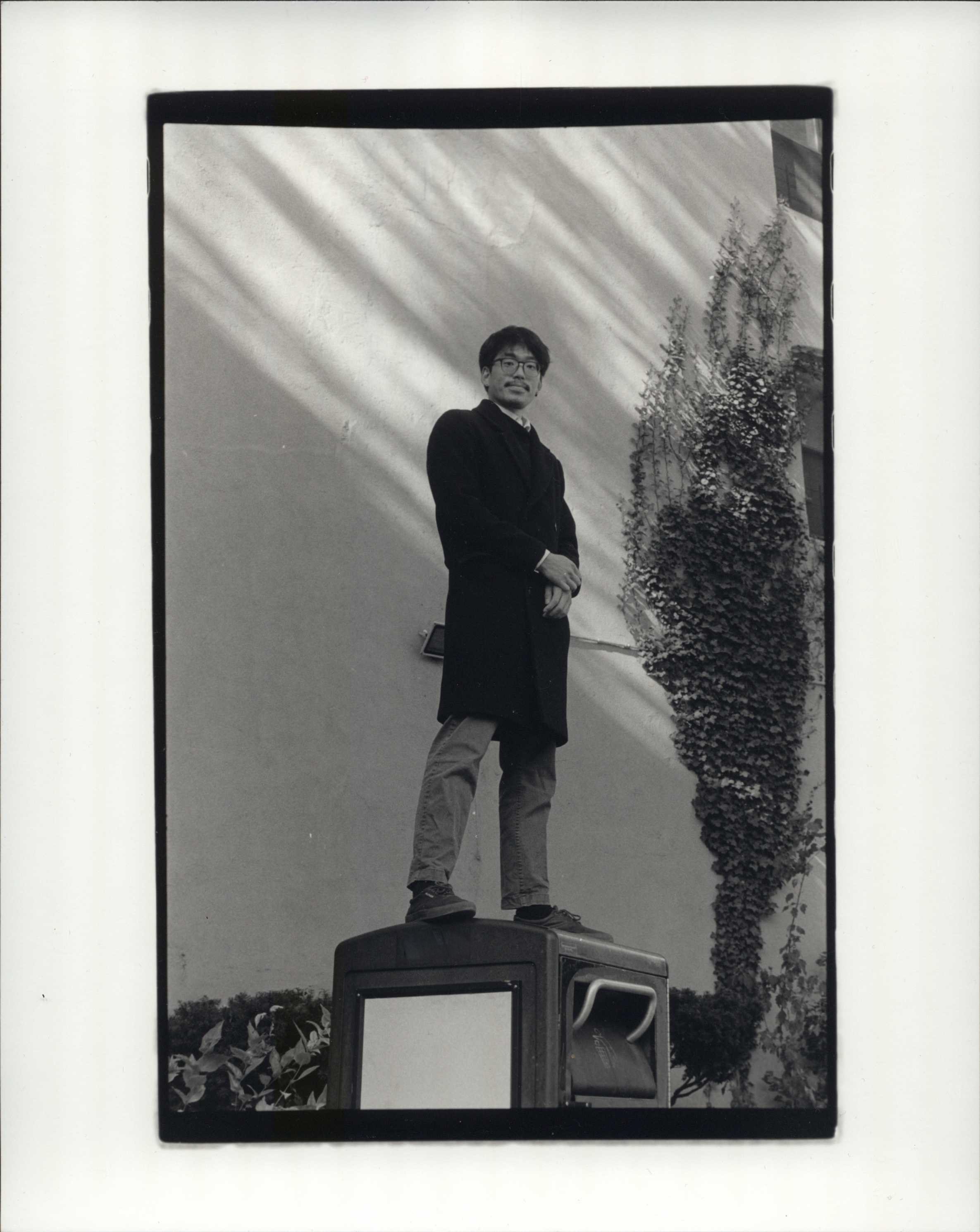

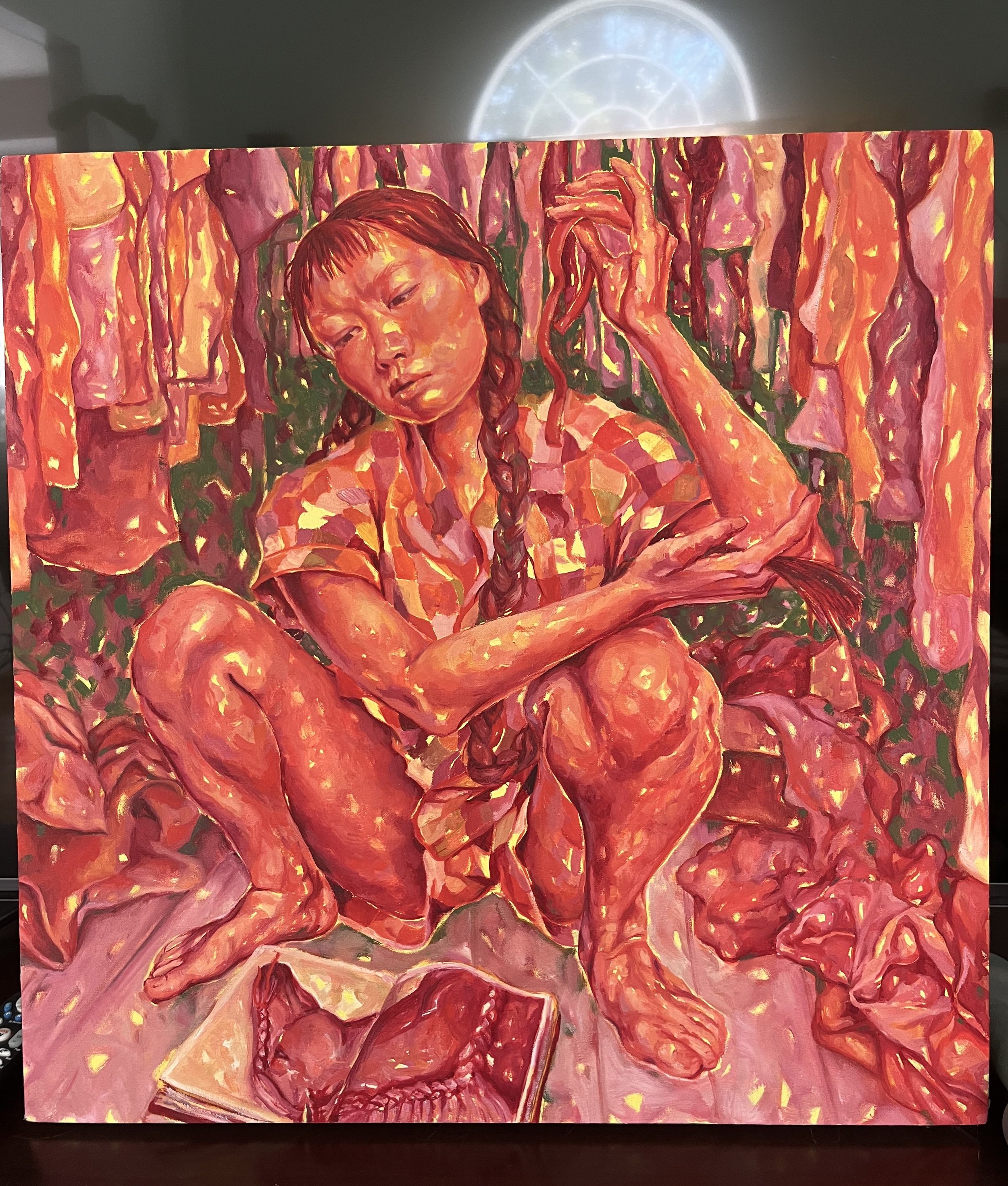

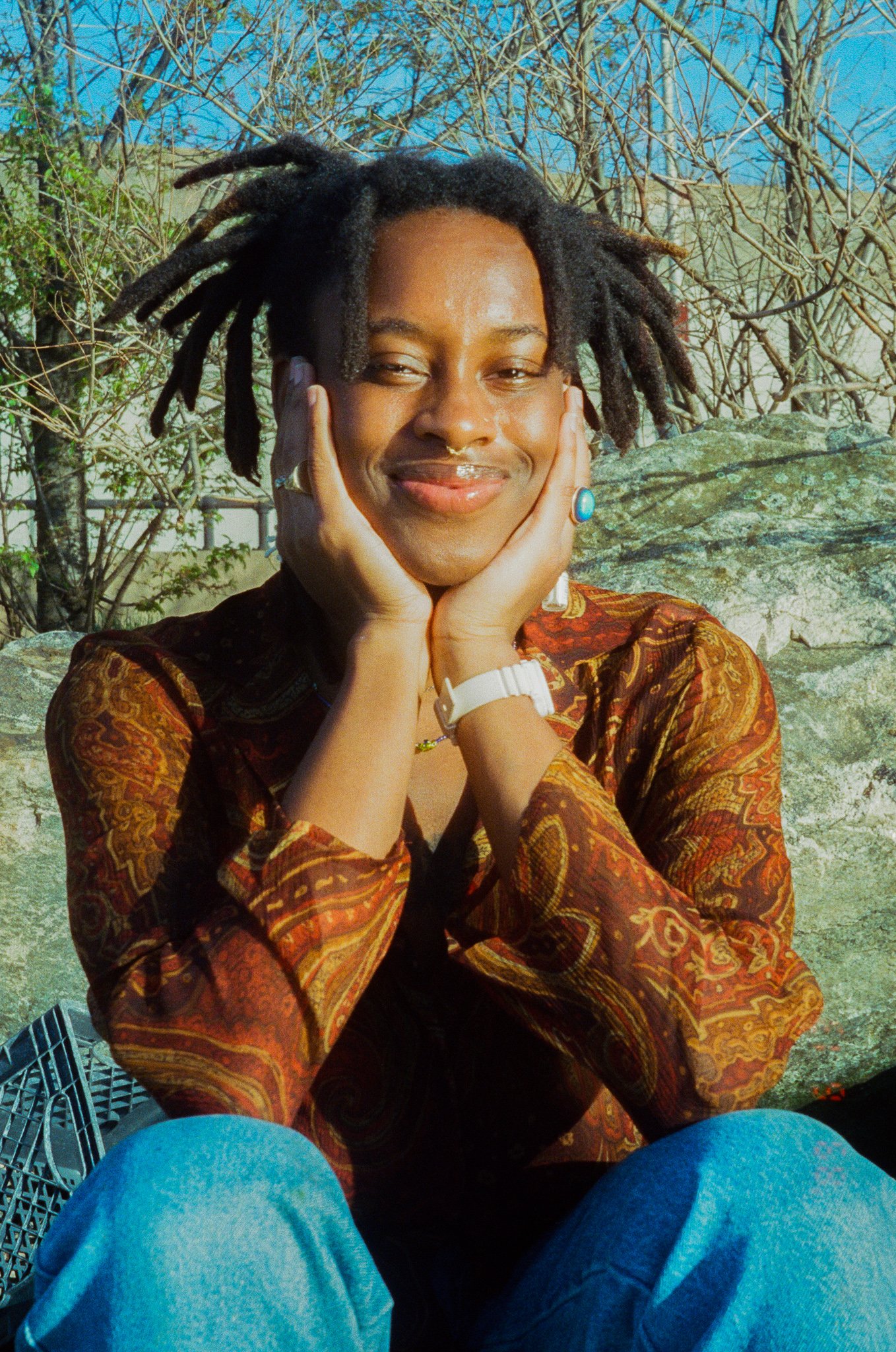

In the beginning, my priority was that my pictures needed to be extremely aesthetic— perfect picture, perfect structure, capturing this impressive moment. And then I realized there was more to it than that. I had to be just as embedded in it as the viewer, and that’s when the world gained more meaning. Highlighting my high school experience, history, or just trying to capture the moments that I felt were important to my narrative. Today, when I'm trying to capture moments in New York, it's more about moments that seem so exciting, but that also don’t need to be perfect. Embracing imperfections or flaws has become a very important part of it for me. I don’t tell my subject to pose in a particular way or do something, it’s more about the fact that I will crack a joke in the middle or goof around. Being able to capture moments that reflect something candid and genuine makes me feel excited as an artist.

MT– Let’s delve deeper into the idea of a photograph transcending the act and becoming a lived experience. How do you materialize the relationship between yourself and the subjects you capture?

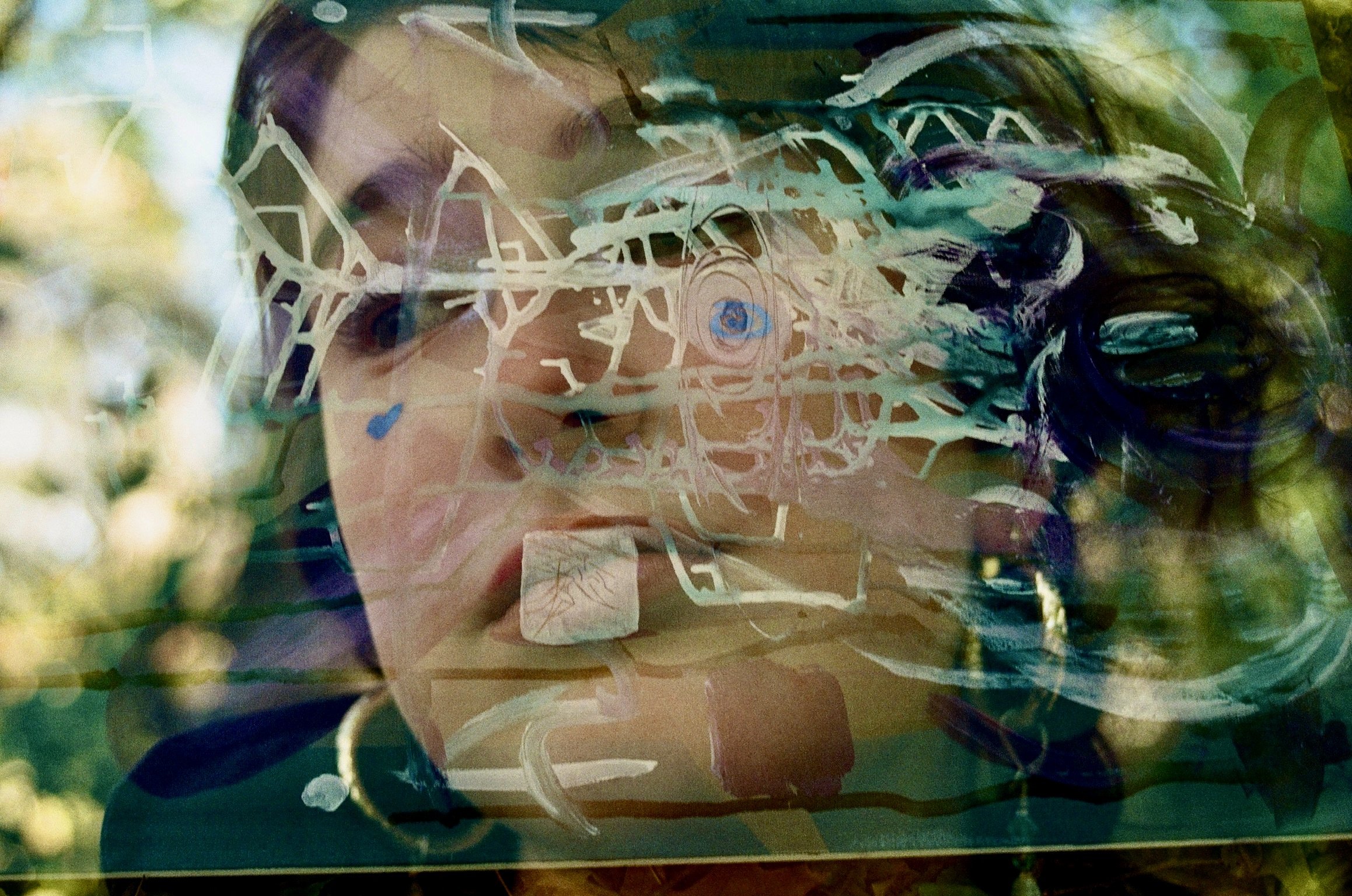

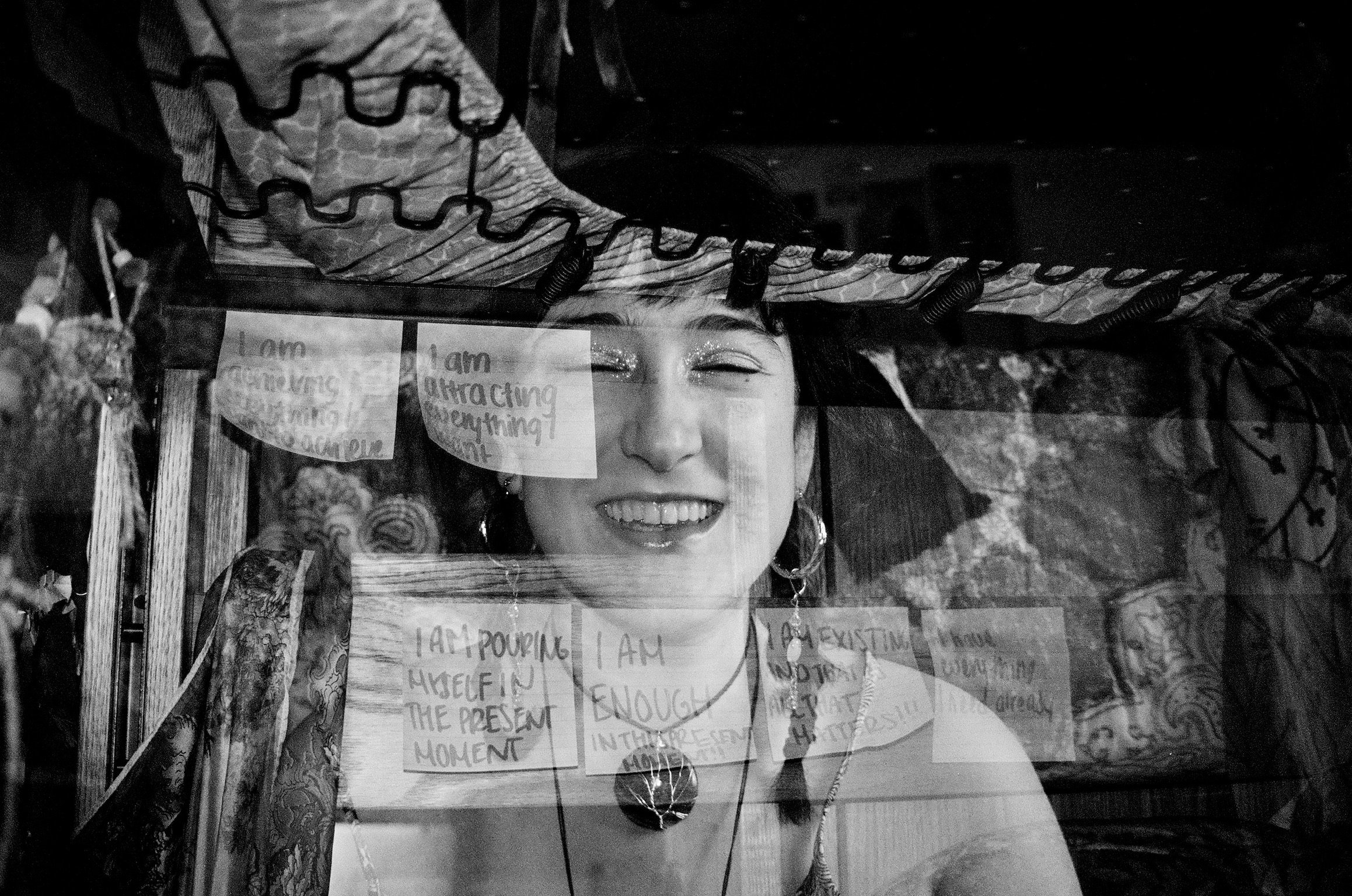

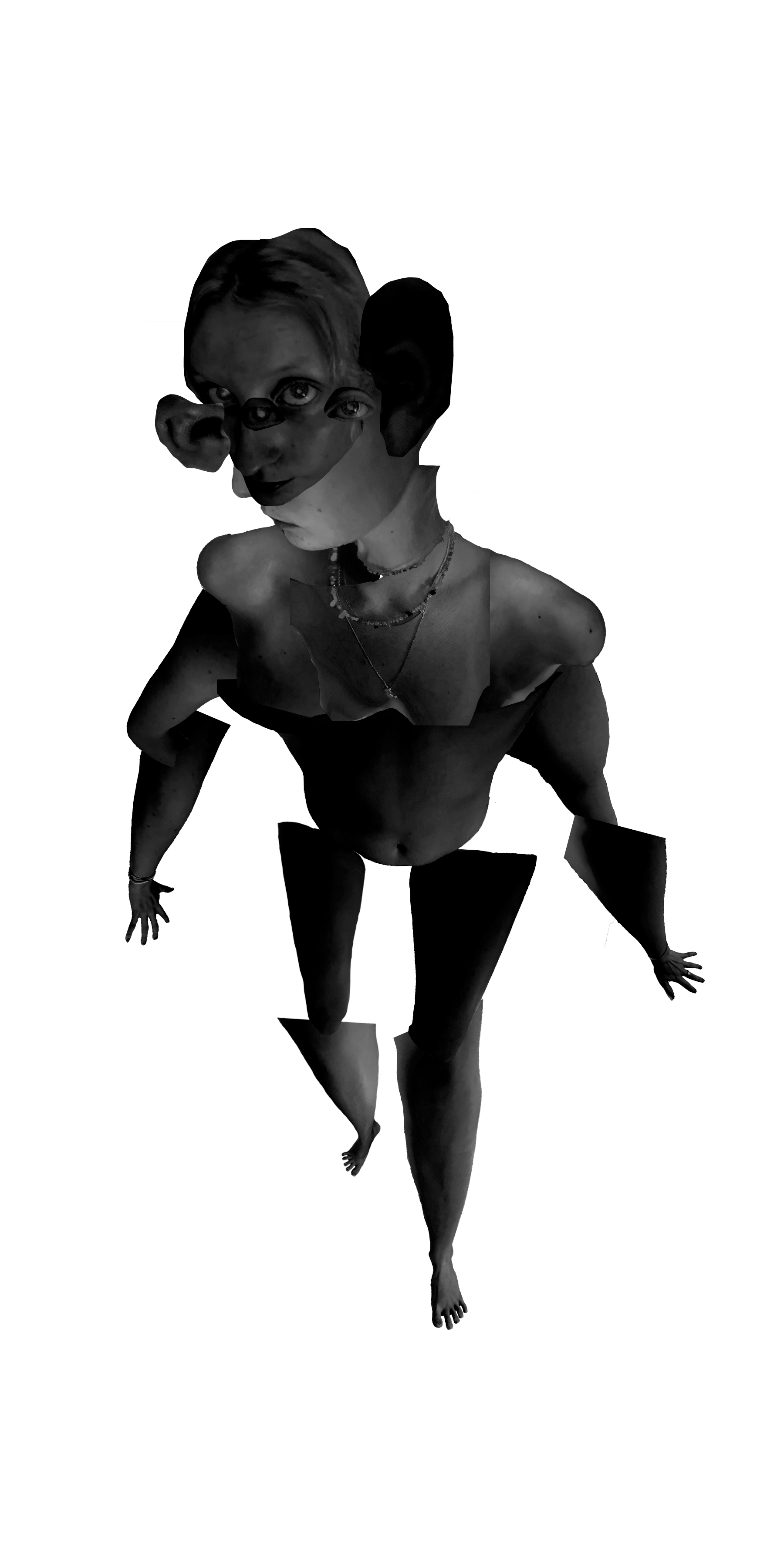

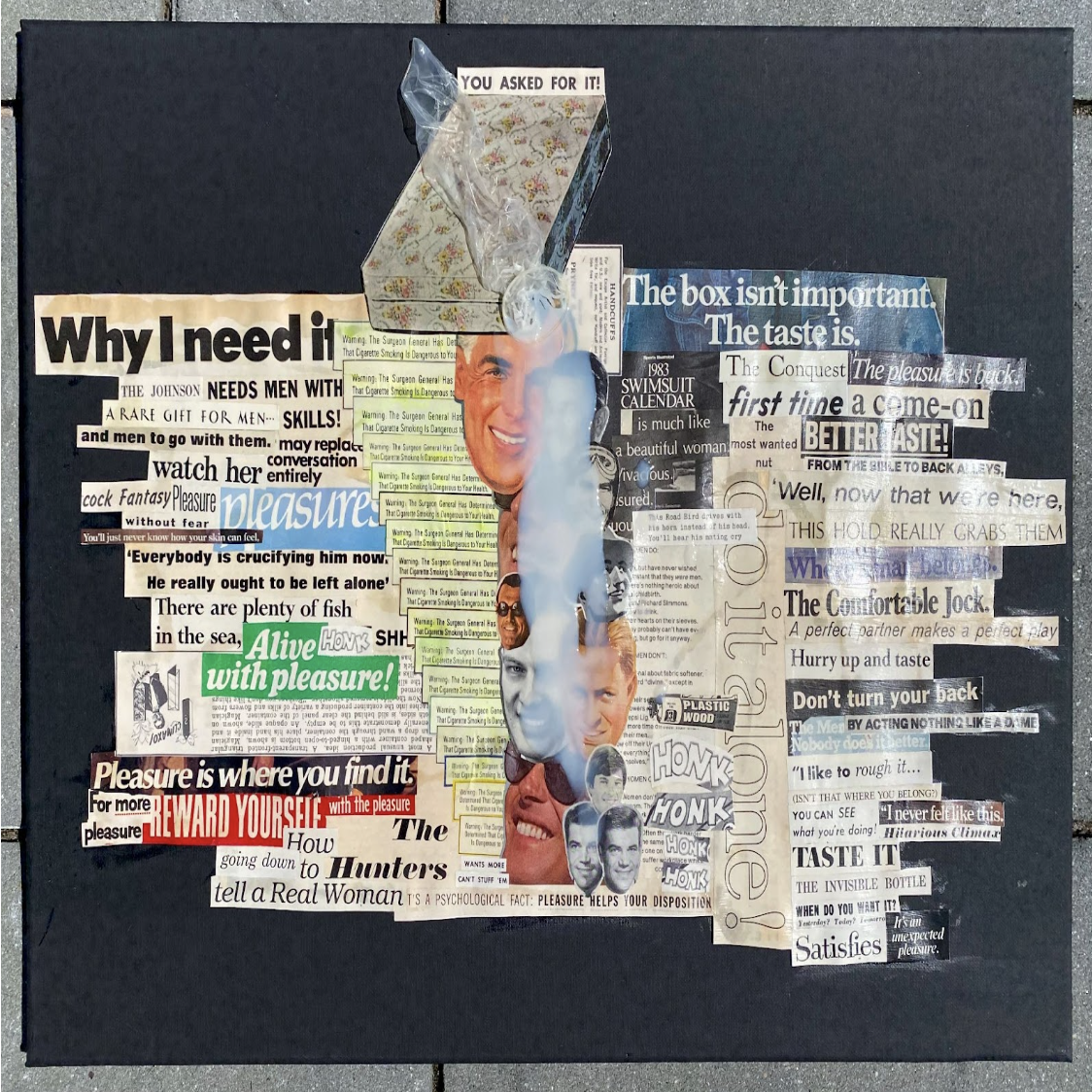

PK– The pictures that I take reflect a relationship between me and the subject which changes based on our closeness and familiarity to one another. In one picture, I captured a friend of mine. We were experiencing a moment of solitude and a feeling of aloneness. We were forming different parts of our identity but weren’t quite sure how to express that. We collaborated on this concept of turning aloneness into something physical. I did a photoshoot about body positivity—that series depended a lot on what I spoke about with my subject. I ended up having an interview process with the subjects, discussing their opinions, their feelings, their insecurities. But I also have pictures where I don't even know the person— photographing someone with whom I have no relationship whatsoever. When I look at my pictures, I get a sense of when I am connected to my subjects and when I am not. In fact, when engaging with any sort of photography, it is very interesting to reflect on whether there is a sense of familiarity or personalization. As far as my identity influencing the picture, when I am photographing, it is very much coming from my perspective and what I want from that moment. I am in control of that, there is a lot of decision-making that goes into that—the framing of the picture, the structure of it, how I like to filter it. All those decisions reflect my perspective of them.

MT–Place and the construction of place are central themes in your photographs. How does the experience of being a resident of New Delhi influence how your identity gets communicated in your photographs?

PK- I have a big attachment to the city that I'm from. Towards my later high school years, I got attached to the idea of displaying everyday people in Delhi. Especially cities in India– it’s easy to take for granted the people and services around you. Being a developing country, the informality of it all inhibits you from appreciating certain parts of daily life. I got very attached to the stories that created Delhi—and back then it came from a need for political activism. Hindu nationalism is a current issue in India. When I was photographing, there were major controversies surrounding the government renaming monuments or highlighting monuments that were made by Hindu People. This meant letting go of a major part of history or framing it as the work of “invaders''. My work was very much in response to that rhetoric. The idea of colonialism is very different to the Mughal rulers—they settled here, colonizers did not. For me, it was very important to highlight that in a way that I could. My photography takes on various approaches, so I don’t have one singular ideology behind it. It evolves as it goes and I enjoy that as well—I don’t want it to be a specific thing, I want it to be fluid.

MT– Would you say then that your work revolves around the constant process of defining and redefining space?

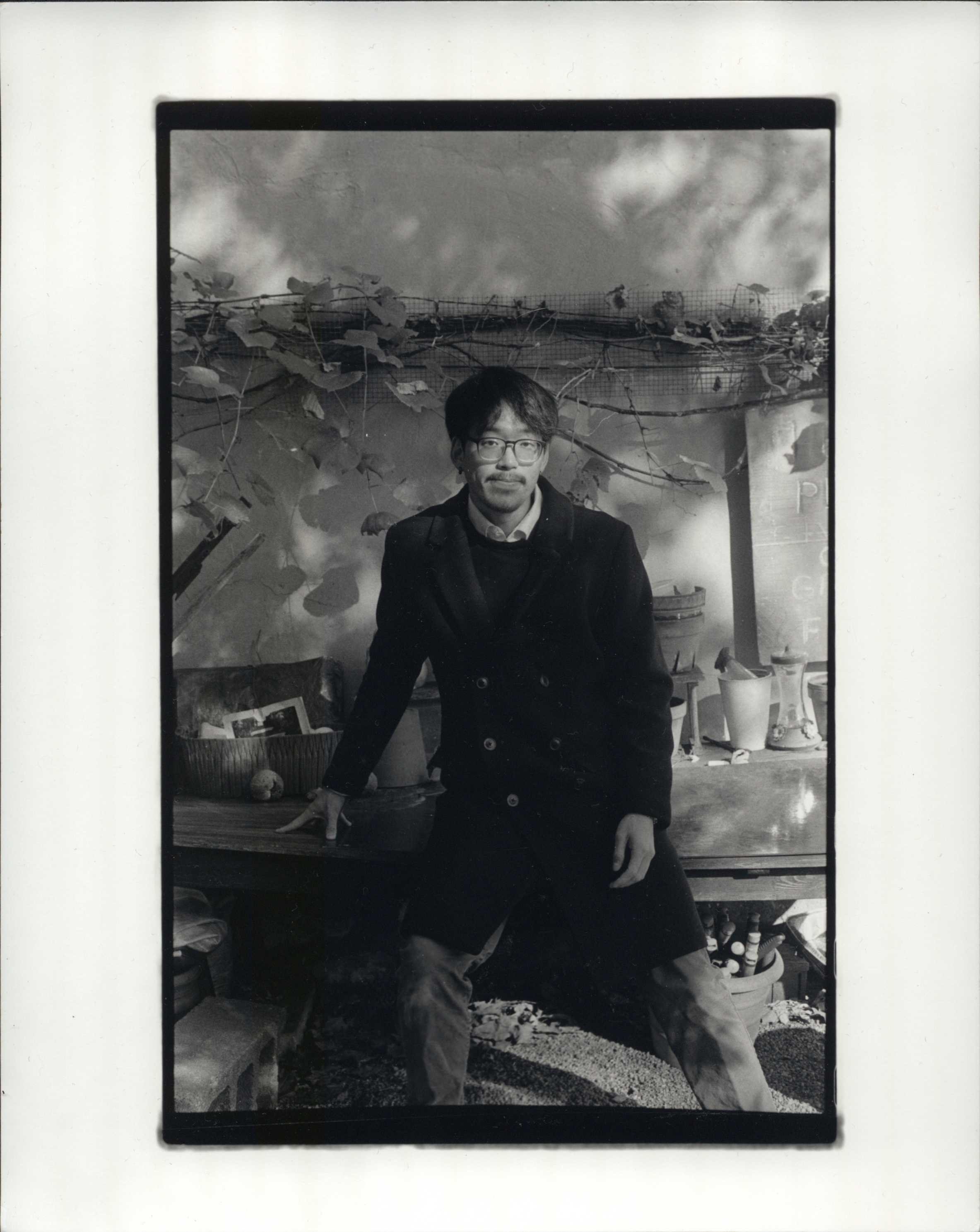

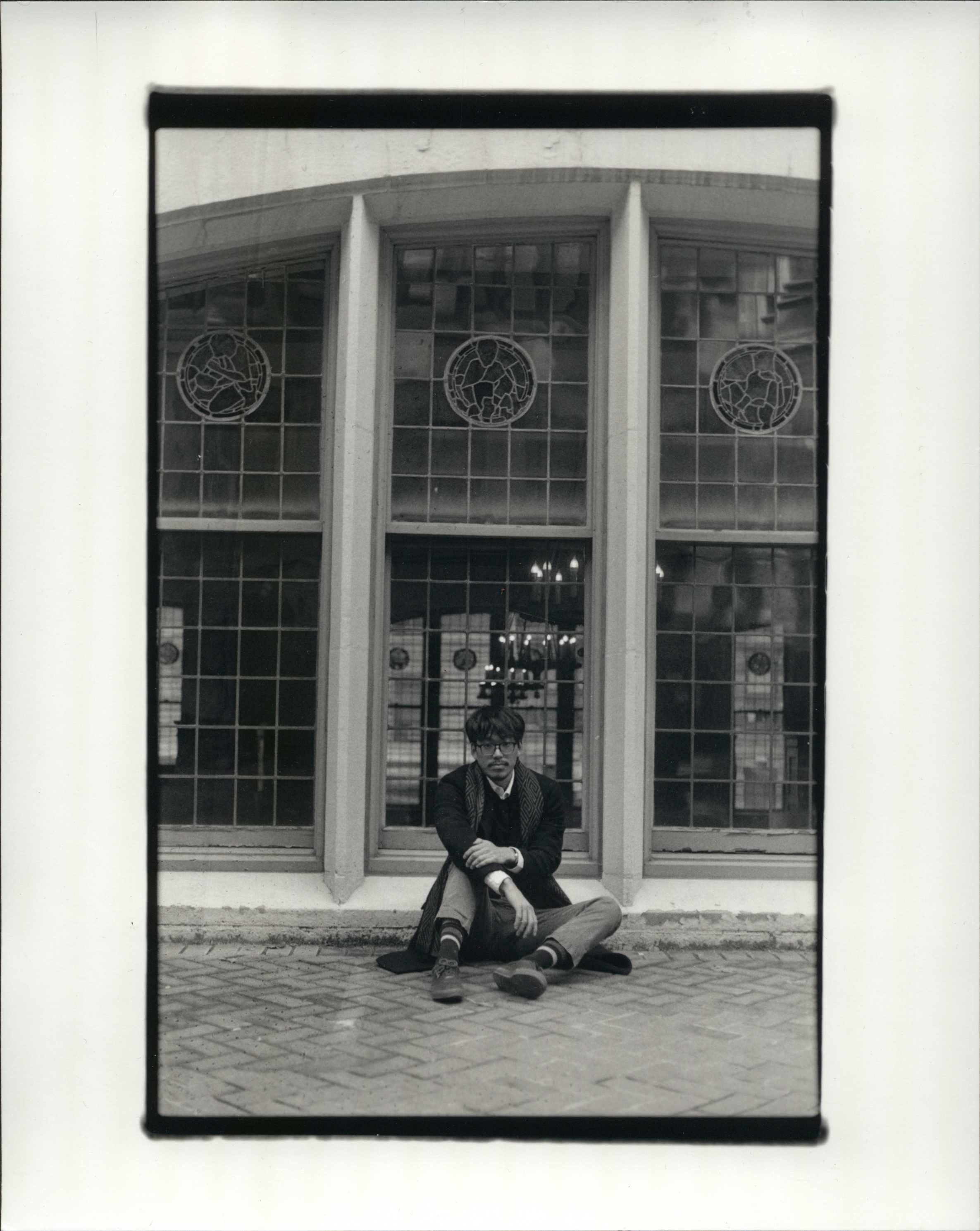

PV– For me, It's taking a space that I'm very familiar with and either reclaiming that space for myself or reclaiming an identity I have, like being a Delhiite… or a prospective New Yorker. It’s taking that space and doing something to make it feel different to me; I try to rediscover something about that space that could either send out a message or highlight something that went unnoticed before, or at least something that went unnoticed by me and others. A lot of it is how I am processing spaces, people interacting with these spaces, and most importantly what it could mean to people who are in those spaces. You don’t realize how much value a space or an object has until you see someone interacting with it in front of your eyes or frozen on the screen. It gives you a perspective of valuing things that may otherwise go unvalued or unnoticed.

MT– I like how you describe actively witnessing people interacting with these spaces as a part of how you relate to them. Would it be accurate to say that you are looking at these spaces as processes rather than as physical realities?

PK– Especially when exploring identity, the beauty of photography is that you get a sense of someone’s background or where they are coming from. I really enjoy exploring that, especially with backgrounds unlike mine– spaces that are unfamiliar, also those that are familiar. Seeing a person in everyday spaces that they use gives you a window into their life– it speaks to their background, and their identity. Especially today, it’s so important to find a lens through which you gain a little bit of understanding of someone else's identity. I think recognizing that diversity in experience, and making it both comfortable and interesting to look at is something that interests me.

MT– Your work has a very clear frame while also being playful and spontaneous – you include serendipitous occurrences like a beautiful streak of light, or an unexpected movement. Do you embrace randomness?

PK— Definitely. I am visiting places and taking photos randomly— It's always fate. The moment is not planned, but I am controlling how I experience it, how I view it, and how I can make others view it is exciting to me. I love spontaneity, it gives me flexibility to try new things and be whimsical. It makes me grow a lot as a photographer to not have a set idea of things and to recognize that sometimes moments will just not work— the not so great pictures that I have taken are also a part of that process. Photography is a fun thing for me and I hope that is reflected in my photos. I am not very serious— I enjoy the randomness and the challenge that comes with it – I ask myself: can I make a good picture out of this, can I capture this in an interesting way? Randomness gives me that freedom to explore, and it adds to the naturalism of it, the idea that this moment is true.

MT– Speaking of embracing the intrinsic elements of each environment, how has moving to New York influenced your photographic style?

In New York, I have been intrigued by capturing contrasts through spaces. For instance, I find Riverside Park fascinating because it is in such deep contrast with its surrounding environment. Photography allows me to get to know the city… feel closer to it. For instance, I did a photoshoot in Queens, and it allowed me to explore a different part of New York that I am not as used to. In the space that I looked at in Queens, it was a very different feel from Manhattan or the Financial district… I would love to get more time to explore the city with my camera and try to learn more about each space. Doing that enhances my experience of New York– it’s my way of processing and appreciating these new spaces.

MT – We keep circling back to this idea of processing or reckoning with different spaces. Would you say that photography allows you to practice gratitude towards people, spaces, and places?

PK– Photography brings me an immediate sense of awareness for the things around me. Through photography, I am able to recognize things, and feel closer to them whether it be people in that space, the space in itself, objects, or things that I find intrinsically unique about that space. That’s what it is for me… it is an enhancement of the experience and a way in which I exercise gratitude for the ordinary– whether it be to a space or a person that I happen to connect to…