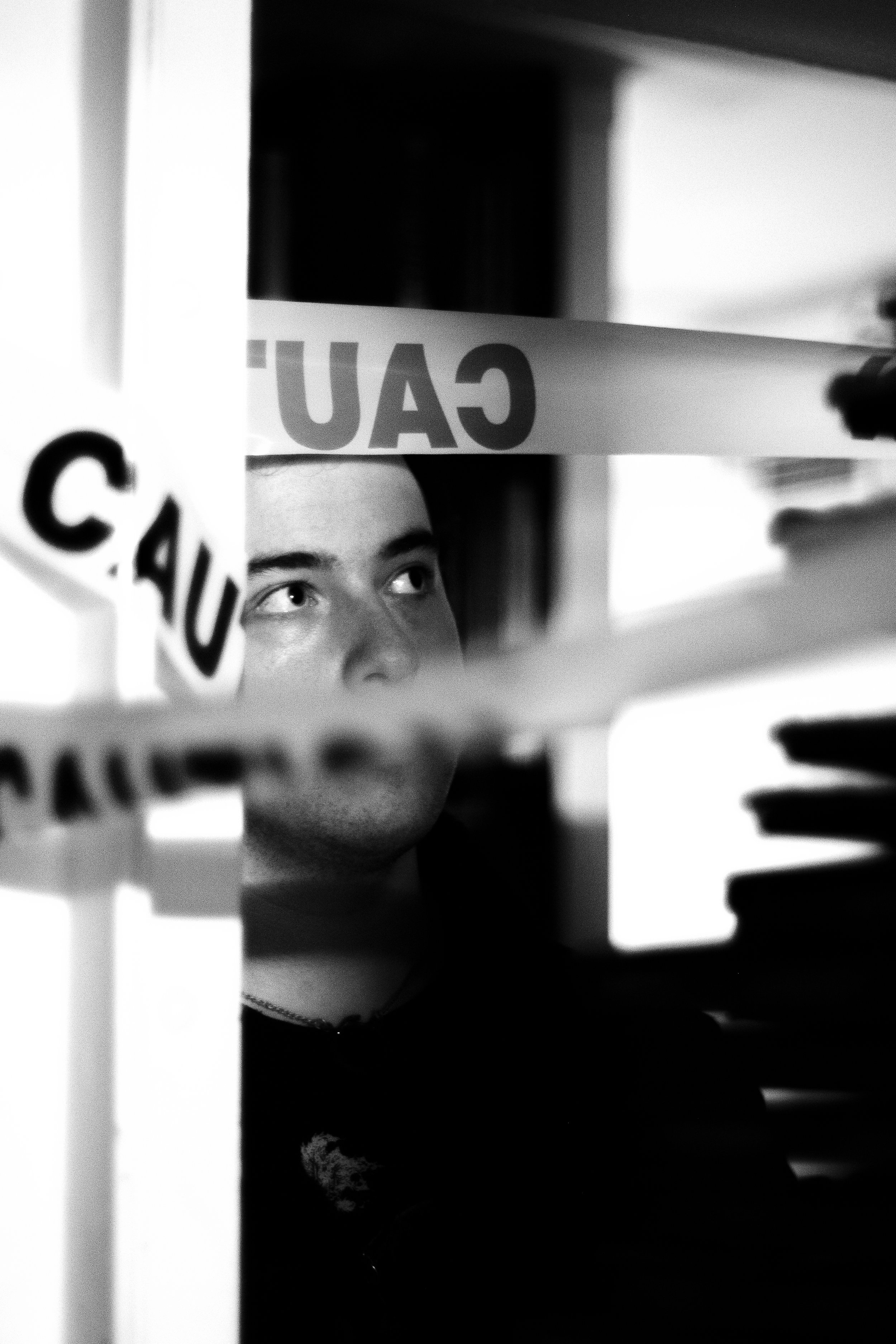

Photographed by Maya Hertz

Interviewed by Isabella Rafky

First, tell me a little bit about yourself.

My name is Amy Gong Liu. I am a senior in Columbia College majoring in Human Rights, English, and Asian American Studies. I write poetry, lyric prose, and essays on the Sino-American diasporic experience, translation between Mandarin and English, love, longing and loss.

What is the Sino-American Diaspora?

The term refers to several different waves of human migration and settling from China. My work focuses mainly on my parents who left Beijing when they were in their twenties and came over to the United States. It’s also about growing up first-gen and only knowing family as my younger sister, mom, and dad—and dealing with the kind of longing for family outside of immediate parenthood. I would see kids with grandparents, aunts, or uncles growing up, and would wonder what that kind of familiarity felt like.

Tell me about how you write and when you started writing.

I’ve always been writing poetry and prose. When I was younger I did so under the guise of anonymity and submitted a lot of pieces to different publications under pseudonyms because I was too afraid to bridge the distance between artist and artistry. I stored most of it in this semi-private blog that only close friends had the URL to, and in it, I rarely mentioned names. Publishing my work and connecting its symbolism to identity or personhood or even my name is only something I recently started doing, but something I absolutely want to run with in the future.

How young were you when you first started getting published? What inspired the pseudonyms?

I think I was in elementary school. It was a class assignment, so we all had to do it, but the story I wrote won an award. There was even a cash prize. My teacher slipped the money into my backpack and said something like: “Don’t tell anyone.” I carried that home; both the money and the symbolism of having words out there crystallized in a form of permanence, but also her words, warning me not to “tell anyone about this.”

So I kept writing, but I kept the writer behind the writing secret. There was a lot of desire to break free from whatever cultural rigidity I was trying to denounce in myself. I think as a child I had this ideation towards whiteness and any kind of assimilatory behavior, and what I was doing behind these pseudonyms and my work was trying to break away from myself.

In your artist statement, you write “my words seek to constellate stories of remaining.” What does remaining mean to you?

I think of it mostly in the context of place. Of people who leave established things, places, families, cultures, or people behind in the hopes of creating or finding something new. Often, when that process of migration occurs, people that either in the place that they left or the self that they left, that there’s something that still hasn’t been filled—and whatever that is is passed on through children and through generations. The kind of melancholy that lingers that is what I'm trying to explore in words. Remaining is something that remains in me, but also remained before, in parents, and what and who came before them.

“Storefront Windows” by Amy Gong Liu

I remember in your poetry you speak about your grandmother and that communication between the both of you…

I definitely write a lot about her. I’ve met her twice in my life, and both of those interactions provide all of the memories and images that I have pulled from when I’m writing. I find that even when I’m writing about immediate family, a lot of it I have to rely on something close to imagination. Not much is known to me about them, and part of the writing process borderlines into the fictional, simply because it’s the only option I have.

In describing your work as almost fiction, was there any semblance of magic growing up? You also talk about the disjointment of religion growing up, so how does that all come together?

Maybe magic isn’t the most specific term. I’m thinking more in terms of fantasy in coming back to this aspect of longing. I write not necessarily to find answers, but to find the questions around these answers. It’s why I think spirituality and religion really tie into a lot of my writing. I come back to memories of specific Buddhist practices done only for ritual; it was never explained to me why I went to the altar and said mantras. Now that I’ve returned, fifteen or sixteen years later, I discover that now, maybe I want to—and my writing is a way of reinventing and restorifying that memory into something with actual meaning.

What is one of the main things that is passed on through you and that you show through your work?

I’ve written a lot of poems and prose about the freedom behind movement, and a lot of this comes from stories I’ve been told about foot binding, and of using ribbons to wrap or control the women in my family. Writing about it helps me to explore the symbolism between physical and emotional staticity, and the trauma of femininity/feminine desire to move still limits me in some way today.

How have you engaged with Mandarin and English in your personal life? How does it come through in your work?

It’s become, as a writer and as a person, the biggest question for me to answer. I tell people that I have a mechanical fluency in English in that I can speak it, that my hands and head know exactly how to work with it. But as I have started writing more about Mandarin and family and culture, I find that English just isn’t enough to be able to capture whatever I’m trying to put on the page. There’s a heart fluency, almost, that I have in Mandarin, that English will never reach. Mandarin exists in something like blood or form or poetics in me. Even in the things that are unsaid.

My latest project is a series of essays about the gaps of translation between Mandarin and English, and the loss of meaning in intimate spaces, specifically between me and my mother. I’m trying to capture the difficulties of growing up and never being able to speak the same language as your own family, and the things that get lost along the way. The realization that I’ve come to, and the realization that the book is coming to, is that whatever language you’re working in—Mandarin, English, whatever—language is only the best option we have to translate emotion and experience. We all know that there are things that we see or feel, though, that no words will ever be able to capture.

“Storefront Windows” by Amy Gong Liu

How does the effect of language come through in your poetry?

Poetry is a chance to suspend or intimate rather than to say something directly. I like working with it because it can capture so much stillness. I can say something in English in it and mean something in Mandarin. That’s the beauty of it.

Did you read poetry before you started writing?

Not as much as I’m reading it now. Part of the beauty in sinking so deeply into writing poetry is that I’m reading a lot more of it. Specifically, poetry written by other Asian American authors. I’m also making an effort to read poetry in translation from Chinese poets like Bei Dao and the other Misty Poets. I love the different kinds of form they work with, and doing this kind of translation work myself, reading and comparing, has been really great in shaping my own work.

Do you like to write within a form of poetry? Do you see a difference between writing within boundaries and writing without?

I used to love working in prose because it was fundamentally about structure. I was afraid, I think, of how open ended poetry could be. But one of the things that I’ve been trying to play around with is mixing different forms in a singular poem: I’m working on something right now, dedicated to my father, that’s written in free verse, and has a section that’s a list, and has a section with a Google search history, and more. I’m just trying to see how they gel.

How does that reflect in the paralleling between your usage of Mandarin and English in your work?

It’s a sense of reclamation in a way: instead of trying to make something familiar to me, I’m simply sharing my own defamiliarization with everyone else. I’m sharing what it’s like to always be jarred in my own body and with my own work, to not be able to be familiar in one language but to use another. That experience of self, the simultaneously confused author and product, is something that I’m trying to understand.

Tell me about your senior project in Chinatown.

I’m working with the Center for Ethnicity and Race Studies on a photojournalism project about Manhattan's Chinatown. It’s called “Storefront Windows,” and it’s form of documentary reporting where I take pictures of semi-reflective window surfaces as an attempt visually trace Manhattan Chinatown’s history of commercialization from the 1950s until now. Instead of a story about show and tell, it’s more of a story about show and sell. It’s a look at the politics of display—who and what are we showing for whom? What are we saying about the commodification and development of land, its residents, and tourists passing through?

So, you do photography, poetry, and essays? Are those the big three for you?

Yeah, and I also make music. I grew up playing piano and I am self taught on guitar; it’s nice to have a break from words sometimes. I’ve been getting back into basic jazz composition and am trying to write from my chromesthesia. Basically if I hear a pitch on the chromatic scale I have a mental and almost visual association with a specific color. The coolest thing about this is once I hear a song I’m able to remember its visual colors and recreate or transpose it onto a piano. Sometimes I’ll listen to a song and translate it out to a visual format, or to try and write words to it.

How are photojournalism and poetry different? How do they feel similar?

I think they’re much more similar than they are different. When I think of a picture and a poem, I think for both to be good, they have to be first and foremost self-aware. Self-aware of their own limitations, of the fact that they are both two-dimensional. Good photography, good writing, good poetry—it does something with its self-awareness, tries to take it and move something or someone outside of the image or text. It transports itself outside of its own limitations.

How does it feel to be a senior? What are your creative outlets on campus?

(Laughs) It's very scary. It’s filled with a lot of uncertainty; not just with the immediate future, but in the far future too. Part of the magic of this semester though, since I’m graduating this December, has been sinking into the communities of artists that I’ve found on this campus and spending time with the people in my life who are also creators. It’s a bittersweet thing to recognize that the community I’ve found through Columbia won’t be the same again, but it’s pushing me to take advantage of it while I have it now.

How has your work changed over the years?

And another question that’s related to this would probably be “how is it going to change in the coming years?” too. To both: I’m actually not too sure yet. Since writing is one of those things that develops and matures alongside you, I wonder if what I’m putting out now may be written in the same way in the future but read differently. I don’t have access to a lot of what I wrote when I was younger, but if I were to go back and read it now I’m sure I’d understand it differently. The same probably goes, in ten years or so, to understand whatever I’m writing now.