Feature by Elena Sperry-Fromm

Photos by Grace Li

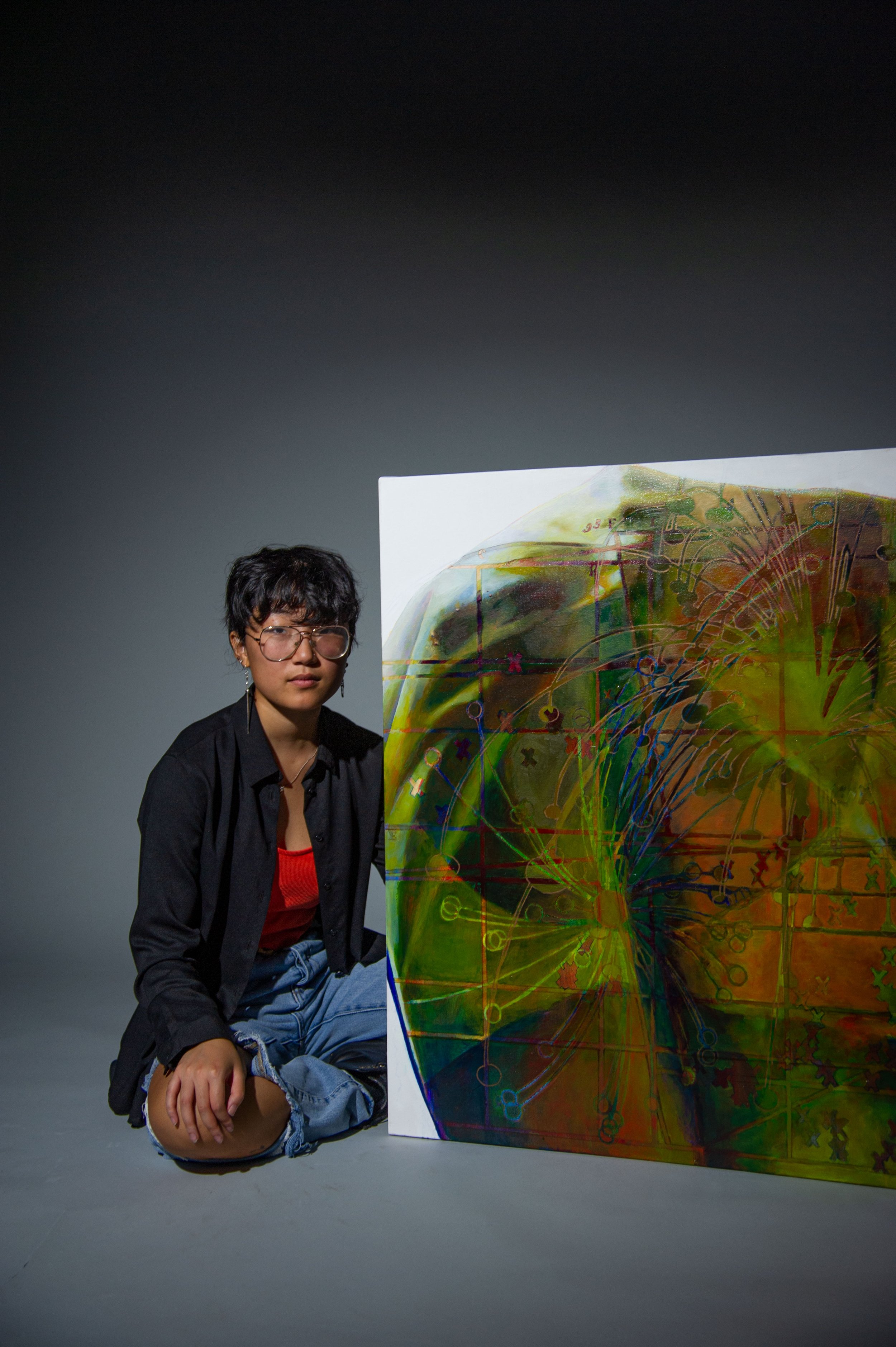

Lilly Jean Cao is a senior double majoring in the history and theory of architecture and visual arts at Columbia College. Primarily working with oil painting, their work combines found cartographies with abstractions of the body, resulting in body landscapes that are embedded with socio-historical meanings.

What does your process look like?

I begin with an idea of something general that I want to focus on. My most recent piece, Self Portrait, Pathological is interested in the pathologizing of the Asian body. It takes an abstracted, close up photograph of my back and imposes related cartographies. There are maps of wet markets, COVID diagrams, old scientific racist diagrams of the skull. I start by painting the body with gestural strokes to create texture. Then I layer one color over that and cover it with tape. I trace a cartography onto the tape, and use an exacto knife to cut out the lines. Then I repeat that several more times with new color layers so that each color intersects and peeks through the subtractive cartographies. This subtractive method works best visually and conceptually as I want to leave that space open for the obliqueness of abstraction. The visual effect resonates with history as nonlinear, as something where all points are interacting with one another. So far I have only been painting my own body, and expanding to depict models is difficult because of the violence of the process. When I work, I’m taping the canvas over, tracing onto it and then cutting out the tape, so it feels like cutting out someone's skin because that’s ultimately what I’m representing. That adds another dimension to the work which resonates with ideas of violence and transformation. [1]

Self Portrait (Pathological)

How does that relate to the dynamics of a map and these intersections of spaces and ideas?

I'm interested in the history of cartography and its relationship to colonialism and scientific techno-rationalist justifications of domination. Cartography is a means to control space and implicitly control bodies. My practice tries to work through those histories by complicating the cartographic form, and by making it more abstract. I extend this by embedding it in the body and considering the way that the body has historically been treated and exploited as a form of space.

One of the most insidious things about modern mapmaking is that it presents itself as perfectly neutral, scientific, and rational. Particularly with early maps that naturalize the colonial project, like maps depicting early colonial settlements as small encampments within a sea of white space representing empty land, which implicitly erases the people who were already there. I try to problematize that by extracting it from its ability to be representative of certain things in totality.

Rhizome Set Drawings

With one of my pieces, Rhizome Set of Drawings, I drew from three different maps. One was an English colonial map of Shanghai, there was a Japanese map of China from one of the Sino-Japanese wars, and the third was a Chinese map of Tibet. All of these are related specifically to ideas of domination and control, but I wanted to complicate that by demonstrating the complexity of the history of China. I’m trying to dig through the nuances of that history by embracing the contradictions of the different directions of control and domination, and through viewing the map as a mechanism and ideology of control.

In the past several decades, there's been a shift in critical theory from historicism towards spatial thinking. Part of the reason for that shift is understanding the ways that social forces, particularly capitalism, are constitutive of spatial organizations globally. This turn to geography is interesting because much of the rhetoric of colonialism is constructed through depicting certain cultures, races, and ethnicities as historically backward. Space as a response to this tendency to historicize is a way of demonstrating that it's ridiculous to portray a people that are existing with you simultaneously as historically older. That space has a lot of liberatory potential.

What does it mean to take something intimate and specific like the body and transpose it into a broader geohistorical context?

I want to problematize the idea that bodies are personal or individual. The way that we treat our bodies and the way that we see other bodies is socially constructed. This relates to the idea of queerness and non binary-ness, and ideas of gender more generally. People often underestimate how the ways that we treat our body are responsive to the way that gender is constructed, or the way that identity is constructed in society. It's not just trans people who alter their bodies in some ways, people do it all the time for medical reasons or aesthetic reasons. I'm interested in the way that skin and surface and body is an expression of social ideas, historical ideas, or a result of them or response to them.

Close

The philosopher Elizabeth Grosz in her book Architecture from the Outside writes about the idea that, “all the effects of depth, of interiority, of the inside, all the effects of consciousness (and the unconscious), can be thought in terms of corporeal surfaces, in terms of the rotations, convolutions, inflections, and torsions of the body itself” As for my own project, I would extend that to include both interiority and sociality. The surface of your body can be an expression of something, but I don't necessarily find it to be an expression of individuality. I find it to be an expression of historical realities. This relates to another quote from Jack Halberstam in A Queer Time and Place that’s really important to me, it’s written on my studio wall, “What constitutes the alternative now is […] a technotopic vision of space and flesh in a process of mutual mutation […] for some postmodern artists, the creation of new bodies in an aesthetic realm offers a way to begin adapting to life after the death of the subject.” I understand the death of the subject as a recognition that the formerly individual or universal subject is really formed out of differentiated but intertwined socio-historical realities (and therefore cannot be understood as either individual or universal, or even really as a subject). My creation of “new bodies” by amplifying “corporeal surfaces” and embedding them with maps and diagrams, is an attempt to picture this different understanding of personhood.

What is that relationship like between interiority and abstraction?

My project and my ideas are indebted to the work of Julie Mehretu. In my work, and in Mehretu’s work, the relationship between representation and abstraction is tenuous, because we're drawing from concrete references and transforming them in ways that turn them more abstract. Abstraction allows you to represent something without being tied to signification. You can start with something concrete and then create an abstraction out of it that keeps the original referent as a haunting of the abstract result. That opens up this nebulousness that’s not doing anything didactic but that is still attending to socio-historical issues. The obliqueness of art interests me and that obliqueness is necessarily tied to the exploration of gender as not being this concrete reference, but an exploration of the way we relate to the dictates of society. The experimentation with representation is also the experimentation with how I relate to my own body, how I relate to history, and how I relate to sociality. Typically, I am depicting my own body, so by abstracting it, freeing it from the ways that the body is typically seen in the media, or the way that I'm taught to conceive of my body as an AFAB (assigned female at birth) person. By exploring the creases and the folds and the hills, I'm allowing the body to be something that it's not allowed to be elsewhere. Elsewhere it's tied to gender, tied to expression; here, it can just be what it is.

Self Portrait (Archaeological)

In your work, how do bodies and their significance fit into both a wider historical context and a particular ascribed group identity?

The way that contemporary artists of color have to deal with identity politics is difficult because at this point, representing a minority group is profitable. So artists who aren't trying to profit from it, who are just creating work that they care about, are being exploited by the identity politics machine. Art becomes constrained by the expectations of your personal identity. Julie Mehretu, to me, is interesting because she's achieved the anonymity of a straight white male artist, even though she's a black lesbian, female artist, and it's in part through abstraction and the refusal to represent a legible understanding of what blackness looks like for her. Instead she's portraying these abstract ideas of urban spaces and architectural spaces which are touching on the problems of identity and of history and of culture. That can’t be reduced to just what her identity is.

Skin I

Within the Asian-American community in particular, I think people are really drawn to symbols, images or cultural artifacts that we view as essential signifiers of a culture we’ve been separated from, but which are really surface-level expressions of an extremely complicated history. My parents are Chinese, but I was born here and I was raised very much detached from my ethnic and cultural context. I grew up in a predominantly Asian suburb, so many people around me have the same experience. I went to an Asian studio in high school, where many artists were trying to make art about their personal experiences by drawing from cultural artifacts that they consider to be representative of China, but really it was food items or stereotypical representations. I understand that too: I have a dragon tattoo and there's this desire to be part of our culture because we've been so separated from it, yet because we lack this understanding about it, we reach out to these surface expressions. Other queer Asian artists who went to Columbia, like Oscar yi Hou and Amanda Ba, deal with these legible symbols of Chinese culture in a way that’s really valuable, I think. Oscar specifically draws on these symbols in a highly self-conscious way and even highlights the disconnect between his inability to read or write Mandarin and his using it as an aesthetic sign. The way that my work tries to do it is more in the way of Julie Mehretu, which is to explore these ideas abstractly and to make my identity less immediately legible even as it is important to my practice. I’m finding a connection to my background through history, rather than objects or images.

You can find Lilly’s work on their instagram @ljeancao