Feature by Julia Tolda

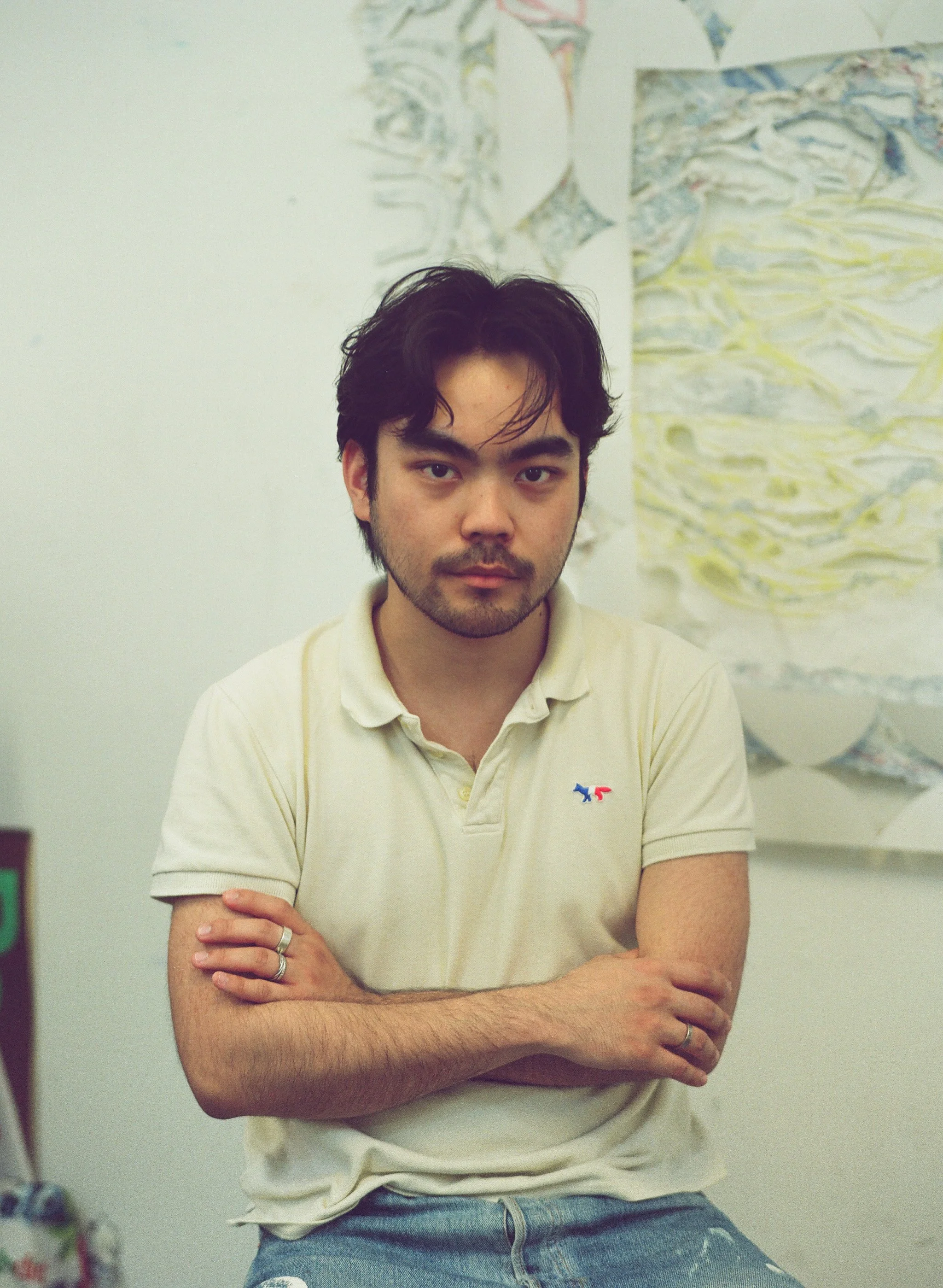

Photos by Amelia Fay

Seiji Murakami’s studio has a folding ladder he rescued from the street. Before the interview began, he placed it between our chairs and asked me to set my phone on it. It’s the perfect spot to record both our voices. This is my first taste of Murakami’s impressive eye for detail, his tendency to look for and find beauty anywhere, and his intuition. As we talk, this becomes clearer and clearer.

Born and raised in Tribeca, senior English and visual arts major Seiji Murakami wanted to stay in his hometown. In our conversation, he beamed that “it all worked out.” Originally at CMU studying art, he transferred to Columbia College for “an experience that felt more informed by other disciplines.” Over the last four years, Murakami noted how all his classes, even those not explicitly related to visual arts, fed into his work.

But Murakami’s love for art began in childhood with his interest in origami. Now Murakami sees how “playing with paper,” and “folding all the time” were formative to his development as an artist. To him, it is obvious: his current work has evolved from and into the after-school activity.

Geometric tessellations were, and still are, his favorite things to make. Repeating fractal patterns permeate his mind, even though he is “not technically folding anymore”. Murakami recounted a piece he had made recently. Working on the floor, cutting and pasting paper together, he intuitively found himself making a hydrangea inspired by Shuzo Fujimoto’s silhouette. “It was against my will,” he added, “almost like it made itself.”

Then, in middle and high school, the study of black and white film photography caught his eye. The realization he “could take pretty good photos and make work that interested [him], reflected [his] experience of the world” was the beginning of Murakami’s understanding of “what it meant to do art and be an artist.” It was this training that taught him “ways to look, to think about what kind of shapes there are in the world, how the camera flattens them, and the importance of light in making and showing work”.

Today Murakami’s interests have expanded to include writing, printmaking, sculpture, and collage. In our conversation, he indicated connections between the mediums. Photography and printmaking, share a relationship to the negative image. Origami propels paper from two-dimensional planes to three-dimensional objects.

As an example, he showed me “Mumur”. It is a large, intricately designed sheet of paper hanging from the wall, something of a cross between a sculpture, a painting, and a collage. From behind the piece, there was a red glow, which Murakami chalks up to its “relationship to the wall”. The sheet is flat, but its reflection on the wall creates depth. And the perception of the piece is reliant on light, much like a photograph.

Murakami’s main interest right now is on how his works can speak to each other, creating an amorphous web of responses and meaning. In their showing together, how is it that the pieces can complicate one another? Pointing at the works displayed around the studio, Murakami went on: “How does this gesture get expanded into another? Or how do the twirls of the fabric complicate the worm paper? How does all that respond to this trim?”

When asked about the connections between art and writing, Murakami talked of the utility he found in this relationship. As he searches for inspiration, Murakami will not only photograph interesting textures but also write about them. Or, as he thinks of a piece, instead of sketching he will write. “You can see it over there,” he tells me, pointing out a stretch of wall completely covered in yellow post-its. Writing is the fastest way Murakami understands his process. “Sometimes the most important thing is just getting something you are thinking down on paper really quickly, and getting that worm out of your head. I’m usually describing the next process or describing the technique. I write to think, to connect my multitude of ideas into a web.”

While writing has not found its way into the work yet, Murakami is interested in trying it out. But that has not been fleshed out, and doesn’t feel intentional at the moment. “I’m thinking of including the post-its of the process back into the work,” he said, “Rewarding the viewer by bringing them closer, letting the words I’ve written act like a lovely treat.”

At Columbia, Murakami felt encouraged to explore his interest in English, mostly because he found reading all different kinds of texts to help form his work.

Anne Carson’s Nox for example, “is all about how the fragmentary arrives to us, and how we have to be satisfied with the information we receive. But she also writes about translation, and the multitude of possibilities. Language is a metaphor for our perspective, every word is a metaphor in some way.”

And Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein influenced his approach to art-making, almost like putting together distant objects into a body. Murakami laughed, “I don't want to say that I'm ‘making the monster,’ but I think there's certainly a fascination with the magic of when these pieces come together, which you didn’t know could be linked, re-made into some larger whole.”

The classical meaning of grotesque came up then, the art style which includes natural, human, and animal forms together. Murakami mentioned specifically the grossness in the works he enjoys, and his fascination with the bodily, the fluid, and the icky. I was reminded of the concept of the “monstrous,” as in, that which cannot be shown, cannot be explained. Murakami agreed. To him, the monstrous is not only linked to Shelley’s monster, but he also thinks of it as a queer body. “I don’t make work that needs to be explained as queer work,” he stated, “it just is.” He recommended the article “My Words to Victor Frankenstein above the Village of Chamounix,” by Susan Stryker, as an example of this link.

As the artist is brimming with ideas, so is the studio brimming with materials. To Murakami, the work doesn’t seem to start or end, the days flow from one to the next. He will set up a tarp and his stock, “which looks like trash but is not”. Then he will pull out sheets, shape, cut, and rearrange as he goes. Working on the floor allows him to shift the work completely, from vertical to horizontal and vice versa.

Back to Shelley, Murakami mentions the “self-generated momentum” in his studio. “A lot of my old work that I didn’t like ends up making its way back into the new pieces. I cut it up, reshape, and repaste it. It gets processed, digested.” While he feels a kind of hesitancy in pasting, pouring, or tearing things up, Murakami sees how these choices are mediated and influenced by him. And that is how the “value added to [the work] is mine, it will always be linked to me in some way”. The fear of overworking a piece is real, but it excites him. “If something is overworked, I know I can pull it off, cut it up, process it, and reincorporate it.”

Murakami is currently inspired by “the micro and macro, at the same time, on the same medium or the same matrix.” Paper as a craft practice, as a medium of collaboration. Entropy formed patterns found in walks, the slow-motion fight between elements, “the flowing of order, from being brought in to dying out, repeatedly”. NASA archives of cosmic images, and cellular images he observed in Columbia labs.

Reflecting on his years at university, Murakami mentioned how the artists he met at Columbia, at CMU, and outside campus showed him “the value added to any work is you”. “The most important thing,” he shared with me, “is doing what works for you, and believing in what you are making.”

Post-grad, Murakami is excited about not knowing what things he will create, and to try and make art outside the school context. He will be traveling to Japan for a year to make paper, as a Mortimer Hay Brandeis Traveling fellow where he also hopes to train in other mediums like metalwork. “I am excited by processes, and techniques that I don’t know yet and to see how they will change my work.”