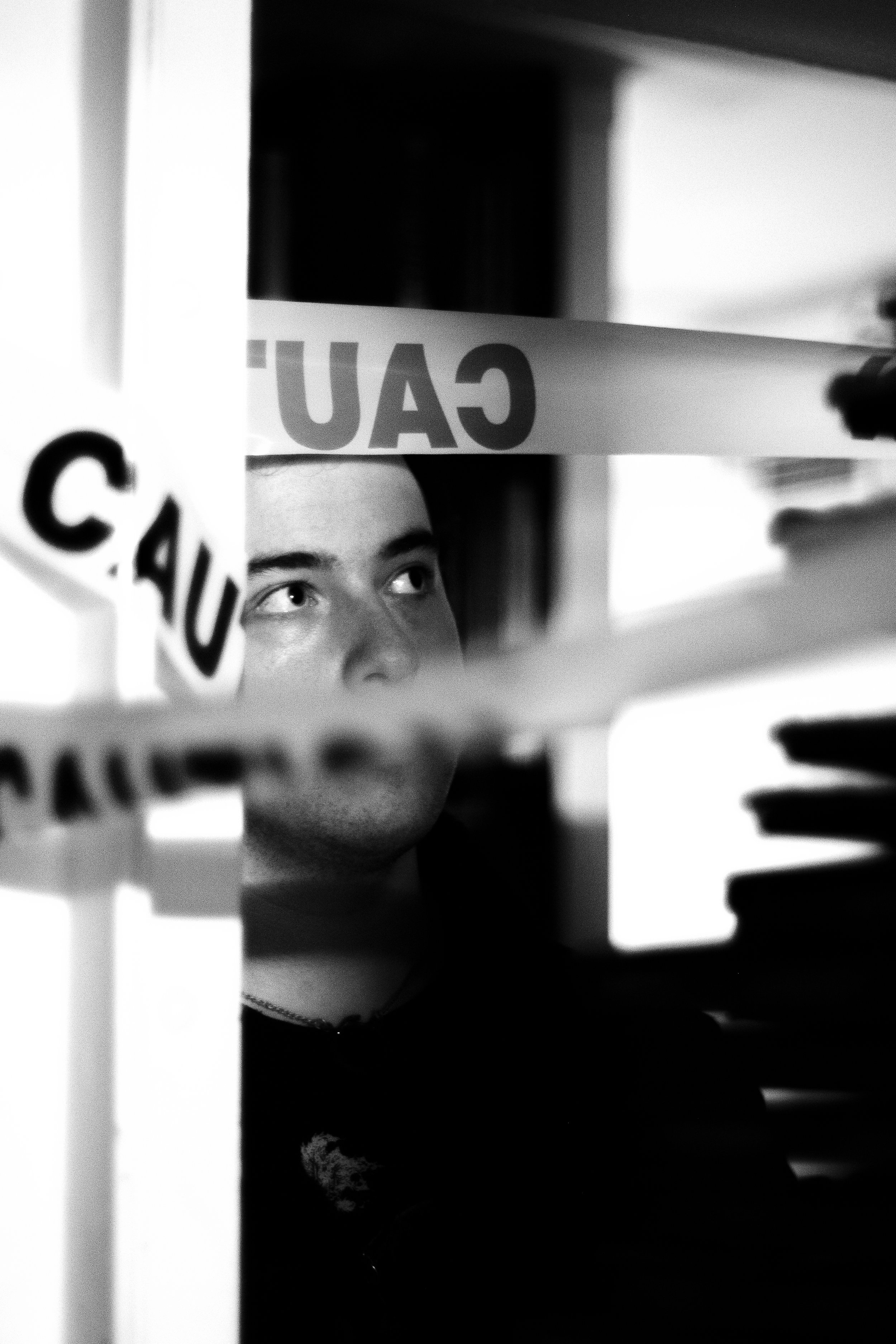

Photographs by Santiago Peuser

Interview by Morgan Becker

Introduce yourself, and your art.

My name is Calvin Liang. I am a senior in Columbia College, majoring in architecture, also studying sustainable development and civil engineering. Most of my art is architectural photography and some portraiture photography, which is done both digitally and on thirty-five millimeter film. I also do sculptural work and casting, which is tied into the architectural work that I do.

Are there specific facets of your identity that you consider essential, or particularly influential, in your work?

In terms of my family, I was always kind of the oddball in the sense that I was doing my own thing, and they had a very different mentality. I’ve always looked at things differently than a lot of my peers growing up. I’m from Arizona, from a pretty conservative high school and town. I think that growing up with that kind of cookie-cutter community, and my weekly routine being so mundane, I tried to find some way to let my inner expression speak for itself.

Tell me about some of your inspirations. Who introduced you to art, and who pushes you to continue today?

My family background is not so artistic. My parents both work in very much the STEM, science fields, but from a very early age I had a creative side. Whether that was in a school art class or music class, I always tried to find a way to have some form of self-expression, that was never really within the stereotypically ‘academic’ fields. So I was always kind of looking for ways to express myself. And that is kind of what’s continued to inspire me till now: is finding an outlet for creativity outside of my academic responsibilities.

Photograph by Calvin Liang

What has influenced your gravitation toward architecture as an art form?

My inspiration for architecture actually came from a lot of traveling that I did. I’m a fencer, and I fence for Columbia. But before college, I was competing for the US team, and it took me to a lot of interesting places around the world; going to Asia, South America, and Europe, and seeing all these different buildings and different ways of living that were so foreign to me—both in a literal sense and a metaphorical sense. Seeing how those communities operated, how those cultures operated, was the first push for me to think about expressing my artistic tastes in this kind of practical construction that is architecture. And the dialogue between art and architecture is something that I’m always working with in my artistic and academic work.

Would you say there’s one place that has influenced you most in terms of architecture?

I think Japan was the big place [of influence] for me. I have family there, but I never really thought about Japanese architecture until I started studying it as a discipline. I ended up working in Japan last summer at an architectural firm and realized that its architecture manifests itself in so many different ways. It literally has completely re-informed how their social lives work, and how they operate, both on an infrastructure level and on a socio-familial level. You see Japanese architects kind of going in the same direction of taking architecture, not necessarily as an academic discipline, but as more of an artistic discipline—expressing artistic moves or going for radical interpretations of what space can be.

What’s your creative process like? Do you know what a piece might end up looking like before you begin?

Whenever I do architecture photography, I’m always thinking about detail. It’s not too often that I try to take a picture of the whole building on its own, or a whole scene on its own. A lot of times the focus is on either some material detail, or lighting detail, or architectural form that I find in a structure or building that makes you think. And that always is something that I strive to do. I want people to really think about the spaces that we occupy. Similar to sculptural work and casting where I don’t necessarily have a direction, it’s a lot about trying to create new language with materials, for example. Whether that means making something solid, like concrete, or wood, look fluid; or making something fluid, like water, feel solid. But I never have like, a hard idea in my mind.

How much planning goes into the architectural projects that require more technical attention?

In that ‘academic’ work, there’s a very formal process that always ends up happening. Whether that’s going through actual structural diagramming, or thinking about basic logistics that are fundamental to any architectural project. A lot of times, especially in more conceptual architectural work, you don’t actually have to think too much about that structural detailing. It’s actually more about your creative expression and developing your concept. And that closely ties into what we call ‘visual arts,’ where it’s a lot more self-expression, or trying to express some kind of idea through form. Those questions of technicality get answered later on [in the process].

Do you have an audience in mind when you work? If yes, does it ever change?

In architecture, there’s always an audience, whether it’s a client or someone else I’m designing for. In terms of photography or sculpture, my content is for everyone. It’s a lot about showing people a side of architecture, or a side of their daily lives even, that they may not notice at first glance—or making them think about the relationships that exist in our daily lives that we take for granted.

Photograph by Calvin Liang

You say you want to make people think in new ways. Do you have an example of a piece you’ve done that embodies that desire?

A lot of the photography that I’ve done, particularly in Japan and the West Coast of the United States, was about discovering the substitutions for things that occur in nature with [a] man-made structure. Whether hills were being replaced by circular buildings, or in the case of a place I visited in San Francisco, where the beach was replaced by this sloped concrete sidewalk that sloped into the water [with] the waves crashing on it; I took a picture of it, just to take a picture of the wave. But when I looked back at it later, it became a picture of a beach, the sand replaced by concrete. These relationships between man made materials and natural materials were some things that I tried to highlight when I went back to the West Coast over the last two breaks.

Do you find yourself working with certain materials more than others? Are there any that you see a big future with in architecture?

Throughout all my work, wood has been the most pervasive. And that’s just because, over generations and cultures, everyone has used wood as a form of housing or as a form of construction. I think there is a reason for that. I think it has a lot to do with the fact that it comes from the Earth and that it can go back into the Earth; whereas, with concrete or metal, there isn’t that same longevity. It doesn’t have a positive impact on the environment. Now I think people are trying to find ways that we can push the use of wood. In the artistic sense, thinking about how we can express something like a wooden house in a way that is inspiring, that isn’t boring—that’s the challenge that we’re faced with now.

What are the merits of sculpture and architecture over two-dimensional arts, like photography or drawing? Or vice-versa.

Architecture, for me, is art that’s trying to solve a problem. With other [artistic] mediums, I don’t believe that problem-solving is necessarily the goal. I can posit questions, or bring attention to details, but I don’t necessarily have to have a solution. I think the beauty of art is that you get people to think about issues, or even just things that exist in their natural state. Different issues and different problems have different mediums. I don’t necessarily have a bias over material or representation. It does come kind of case-by-case for me, really. My sculptures are mostly castings, or types of ‘outside-of-a-scale’ studies of construction. So the result of that is they answer very abstract thoughts, or attempt to resolve very abstract notions or concepts. And so I don’t see myself ever really working with a sculpture that would just be the ‘solution.’ For me, that would be kind of antithetical to my thought process.

Would you consider architecture to be representative sculpture?

You’ve hit it on the head. Architecture is the final product—the final model that’s a cumulation of these sculptures and castings and material studies and fabrications that you do. It's the summation of all those questions you’ve asked. Architecture is always toeing the line of art and science, academic and artistic, and that’s what I think is really beautiful about incorporating art into the process.

What constitutes a successful photograph?

A successful photograph isn’t just taking a photo of an object. I think there should always be something that you’re trying to bring attention to that takes more that, maybe, a quick glance. That might mean that you have to circle back to the photo in a week, or a day, even. What I want a photograph to do is bring attention—or even evoke a feeling. That doesn’t have to be super serious, but even just getting people to be like, “Oh, that’s really cool.” Bringing [up] an emotion, basically, should be the goal of a photograph.

When you say ‘circle back,’ do you mean that you can come back to a photo and realize that it evokes something? Or do you know prior to taking it that it’s going to have a desired effect?

I think the former is what I was going for. That’s a very technical thing that I’m not the authority to speak on; but for me, what’s great about photographs is that you have a slice of time that you’ve frozen there. And you might be able to circle back and say, “On this day, the light that filtered through this window was super beautiful;” but when you took it, maybe you weren’t focused on that, maybe you were focused on something completely different. And what’s nice about photographs is that you get to look back on moments and really think about what that day was like. It’s a lot of reflection, and I think that is the beauty of it.

Outside of the visual arts community, what are some of your biggest influences?

In general, having a separate space within architecture has been really interesting and eye-opening for me, to think about what kinds of questions I ask. That mainly stems from first coming here, and not really knowing what I was going to do and doing photography and sculptural art without really any direction. The great thing about Barnard’s architecture department is that all the other students are also working in other disciplines. The richness of that is you get to draw from their walks of life, and see how they’ve interpreted types of architecture. From that, you can circle back to other constructs and notions. That’s definitely a community that I treasure a lot. Also, music has always played a role in terms of evoking a feeling that I want to emulate in my work. Figuring out where the music starts in something visual or tangible is a fun thing to play around with.

Are you working on anything currently?

Currently, I am working on a small, independent architectural project [in] which my friends and I have decided to let loose of the reigns of convention. We’re designing houses for extreme situations, like, what does a house for just two cats look like? Or, how do we fit three generations of family in a forty foot by twenty foot New York apartment? It’s just pushing the extreme questions of architecture [so] that people would be like, “Oh, that’ll never happen.” But the reality is that sometimes these are cases that exist. It’s this exquisite corpse of absurd questions that people don’t think about when we think about the space that we live in. That’s kind of the move that I’m always trying to go for.

Photograph by Calvin Liang

Anything else that you’d like to add? Closing remarks?

If students are interested in submitting architectural work, or commentary on architecture, the Columbia Barnard Architecture Society does do a publication at the end of the year that they can submit to. And that’s at bcarchitecturesociety@gmail.com. Other than that, people can find me on Instagram.