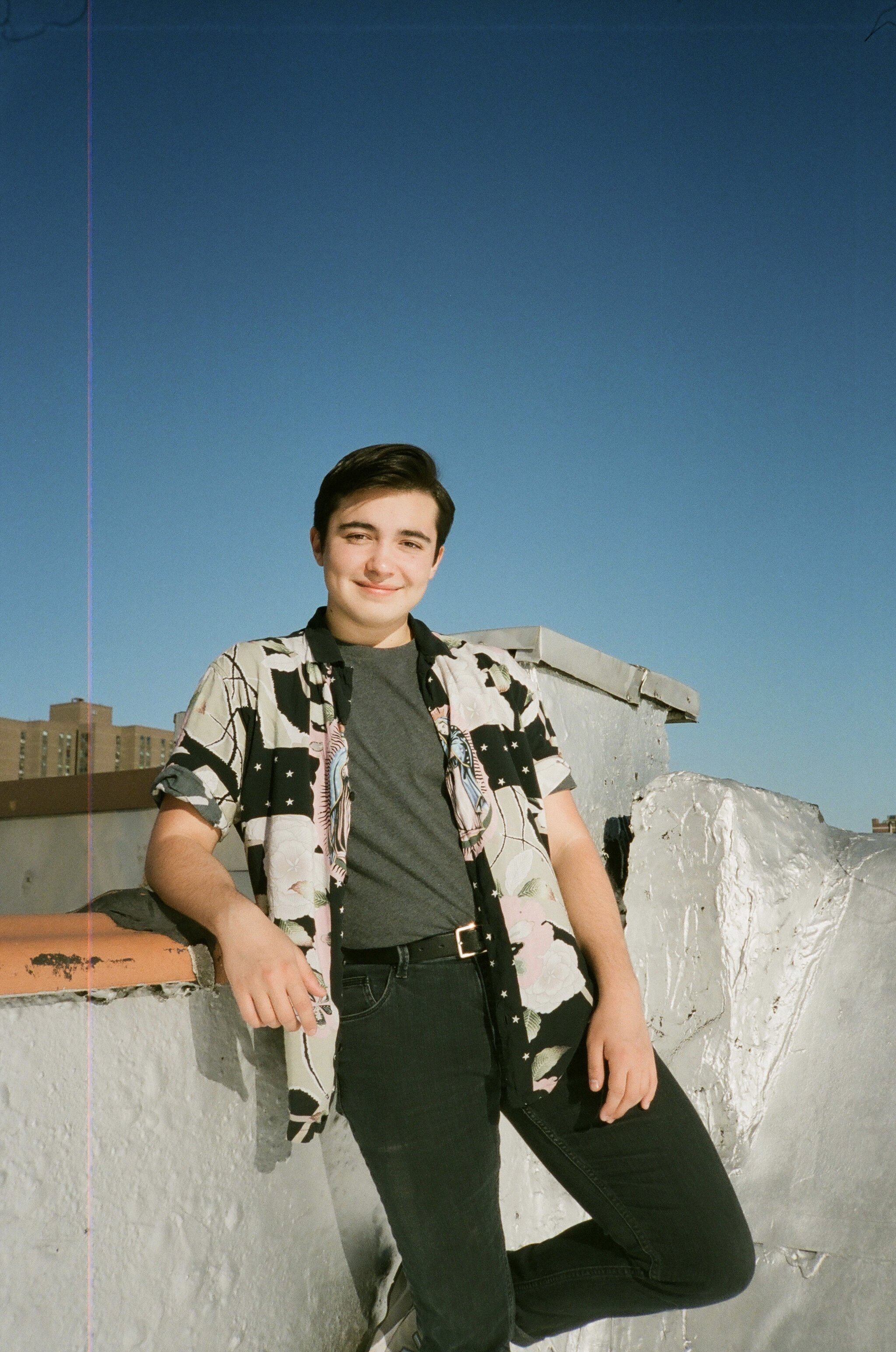

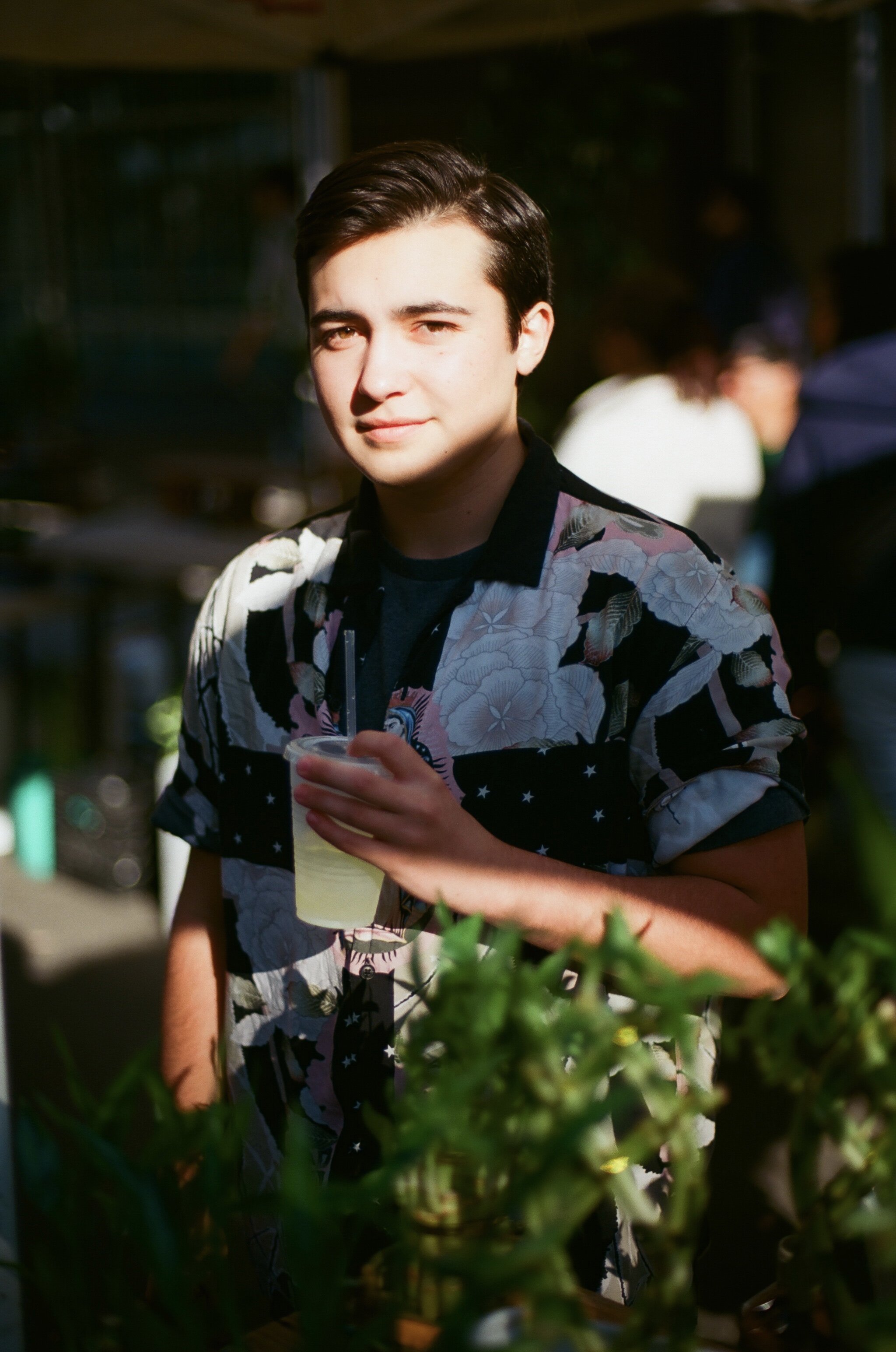

Interviewed by Yosan Alemu

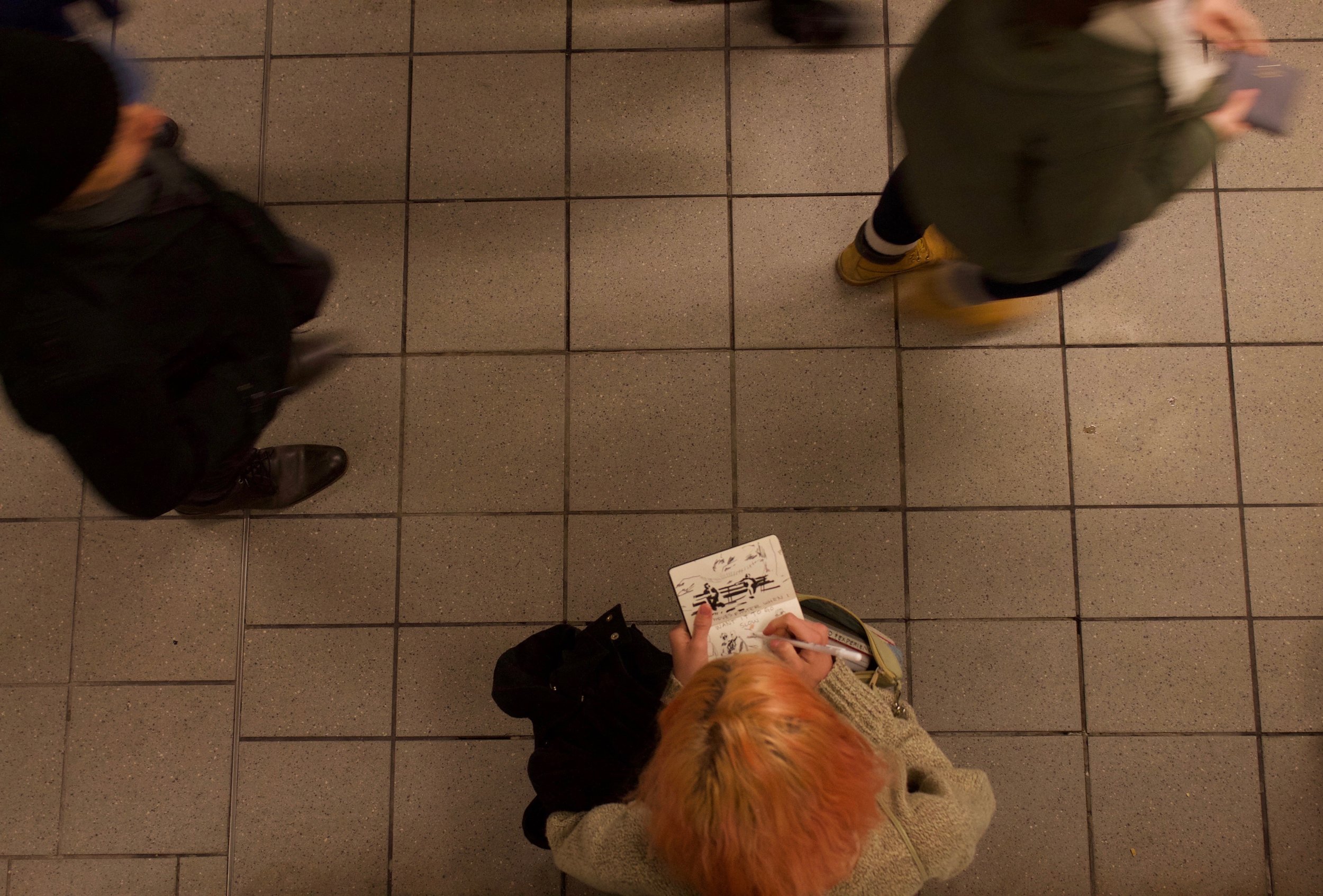

Photographs by Caitlyn Stachura

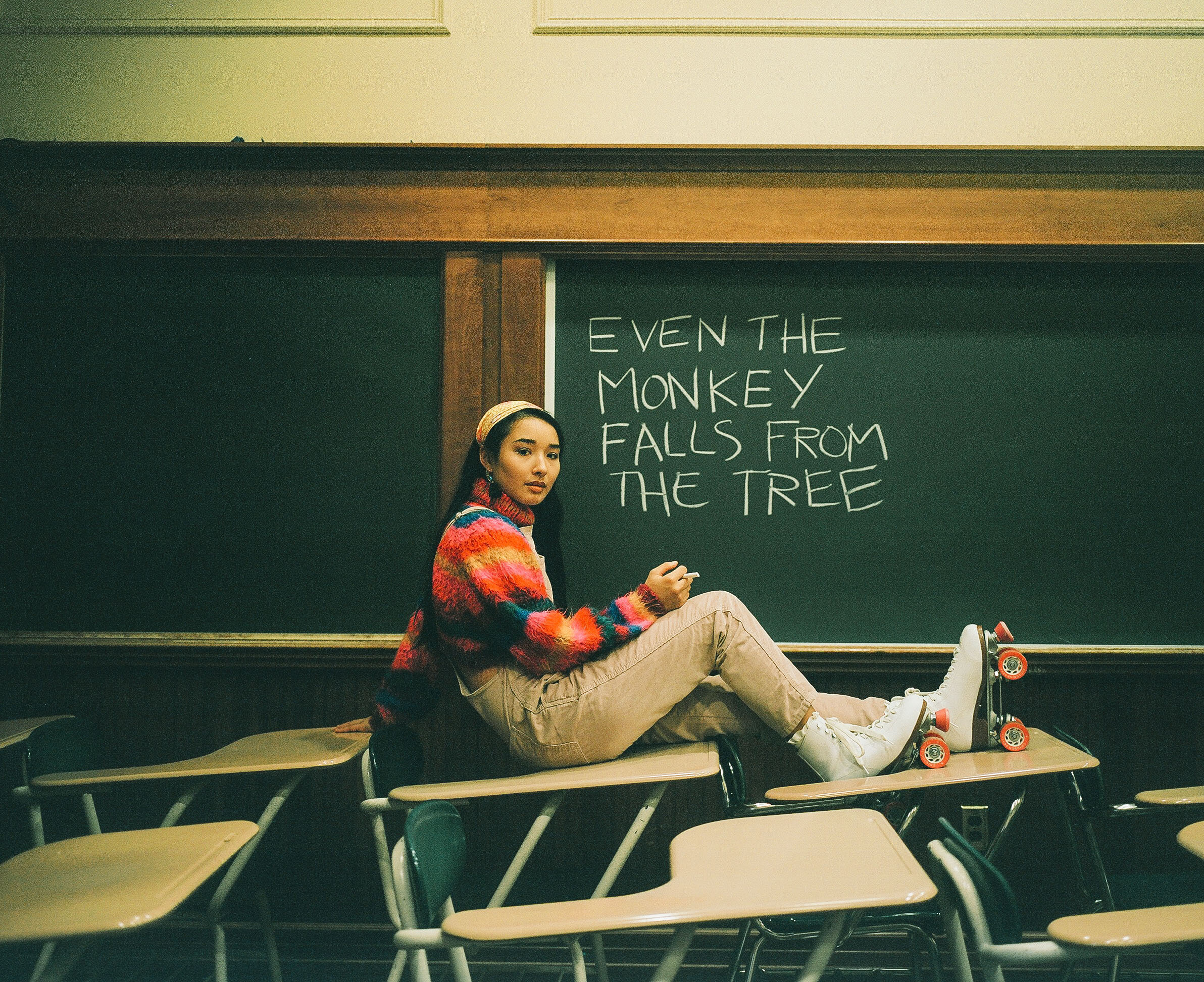

Amber Chong is a junior at Barnard College studying sociology and education in the Urban Teaching Program.

What is the ceramic process like? What's your favorite part of the process, if you do have one?

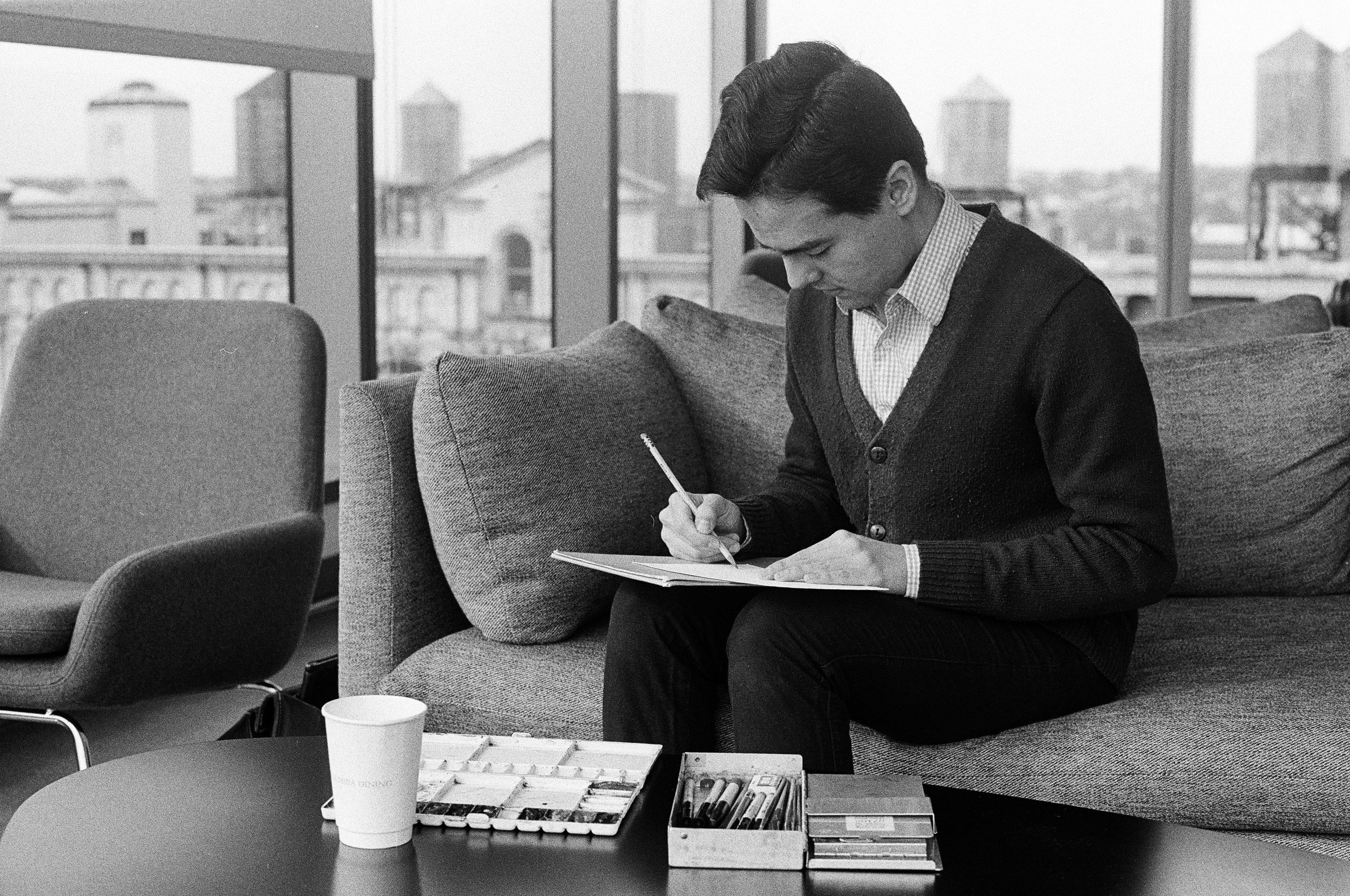

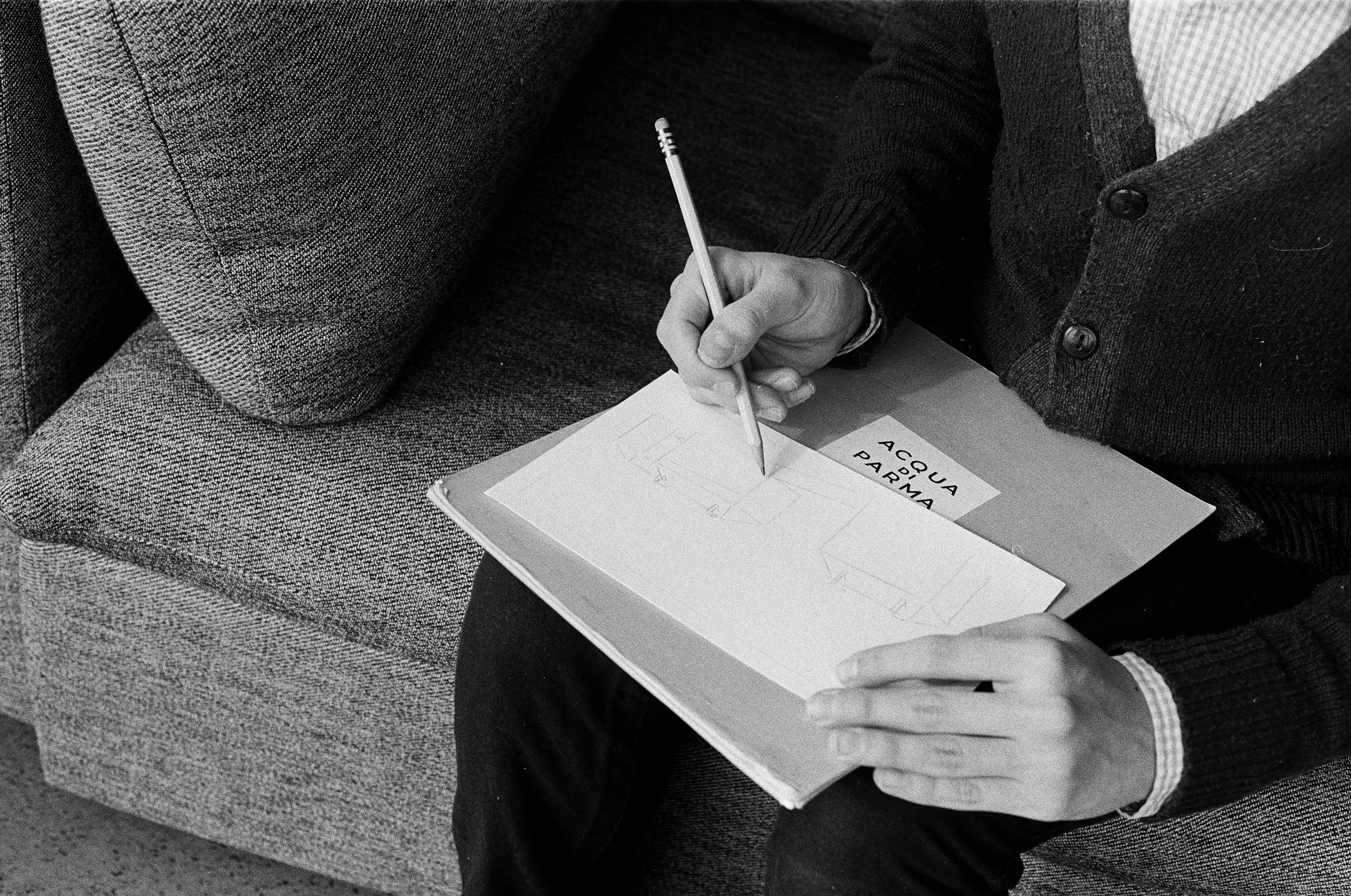

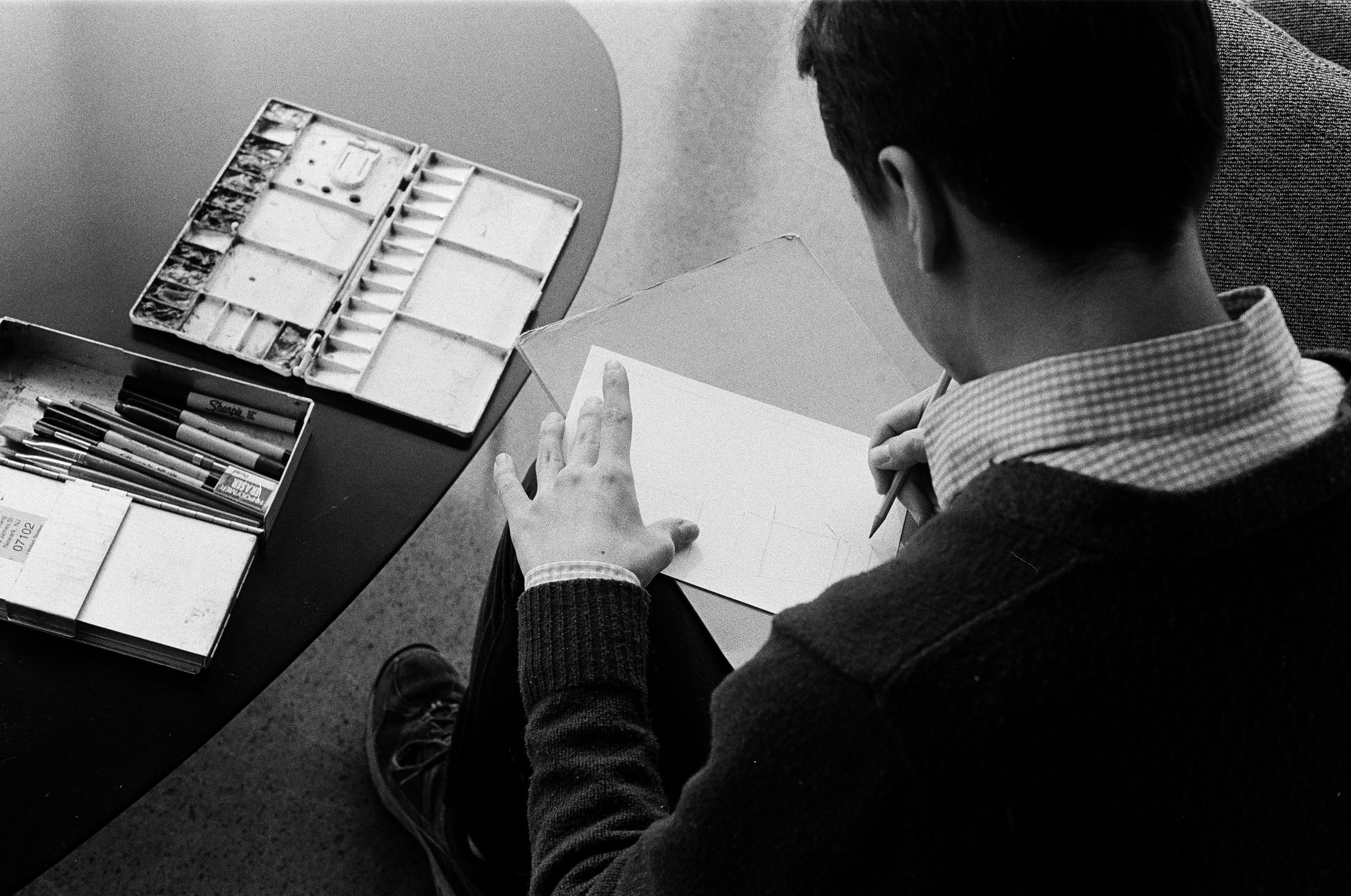

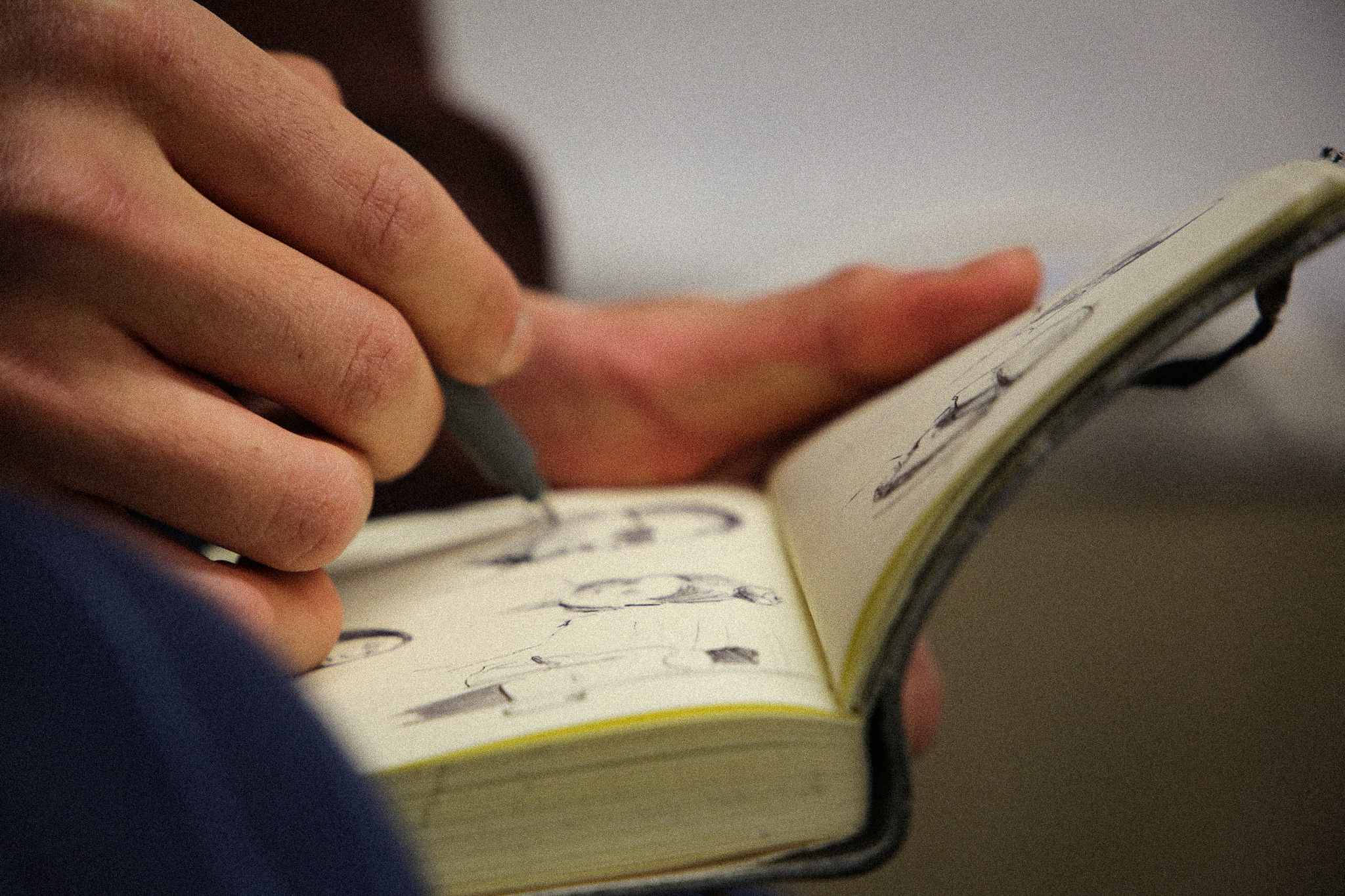

What is the process like? Well, I usually start out by sketching the general shape that I want to make, and then you decide how much clay you need for that. You wedge it—the clay—and get all the air bubbles out of it. And I make a lot of stuff on the wheel. So I'll smush the clay onto the wheel and get it centered. See, you want [the clay] at the very center of the wheel so that your piece will be symmetrical. This part usually takes the most time to learn, and the most time to get it actually there on the center. After, you sort of just pull the clay around into the shape you want while still being mindful of the center. Also, a lot of my pieces have hand-built attachments, so I build those separately and kind of pop them onto the piece. Then the piece goes through the bisque kiln. It gets fired until the clay hardens, and then I glaze it! I really like the glazing process, because there's a little bit of unpredictability with it—and I make a lot of the glazes because I work at the studio, and part of the job is to mix [them]. It's become really exciting now that I understand the chemistry behind it. So after I glaze it, I put it into the glaze fire and just kind of hope for the best!

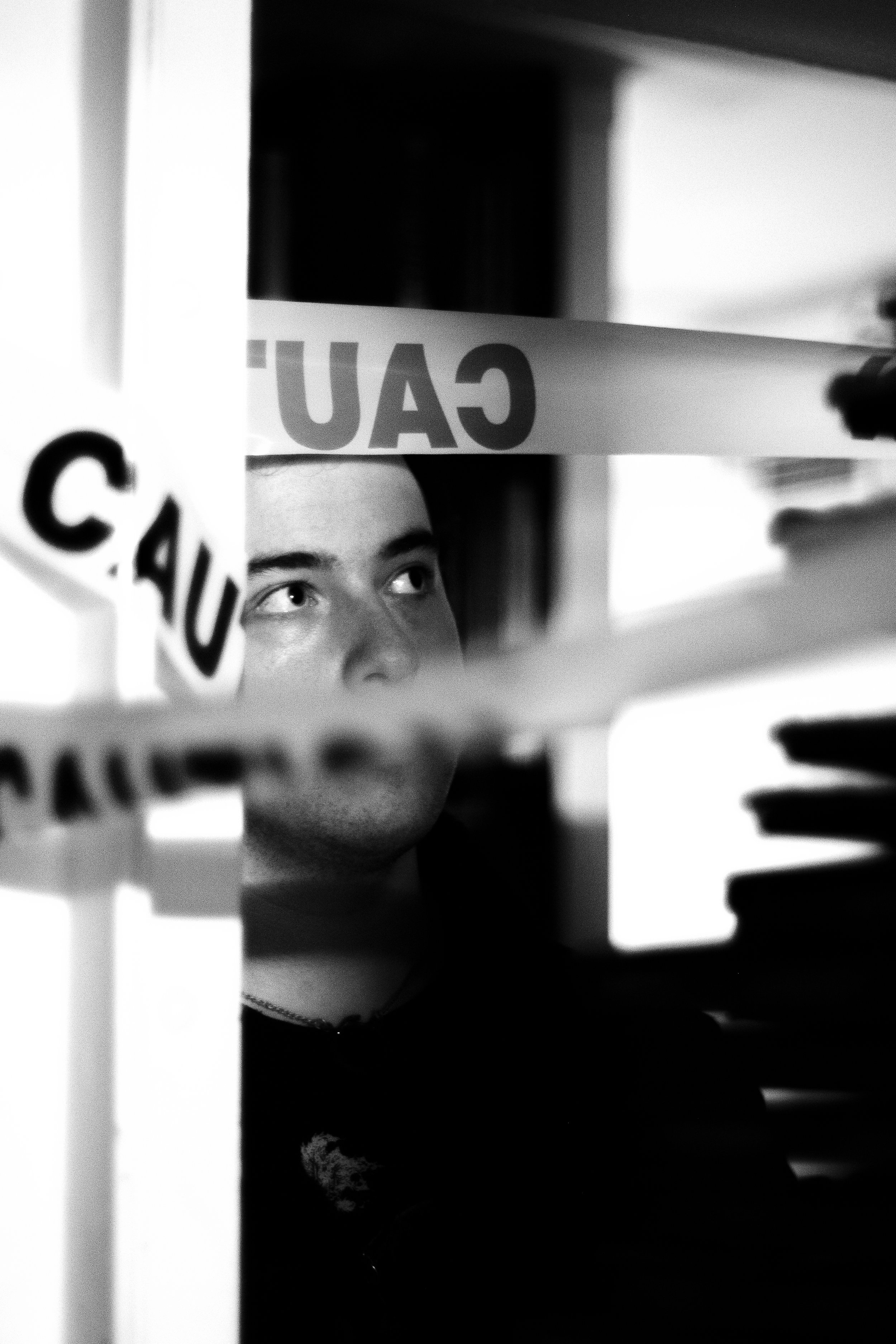

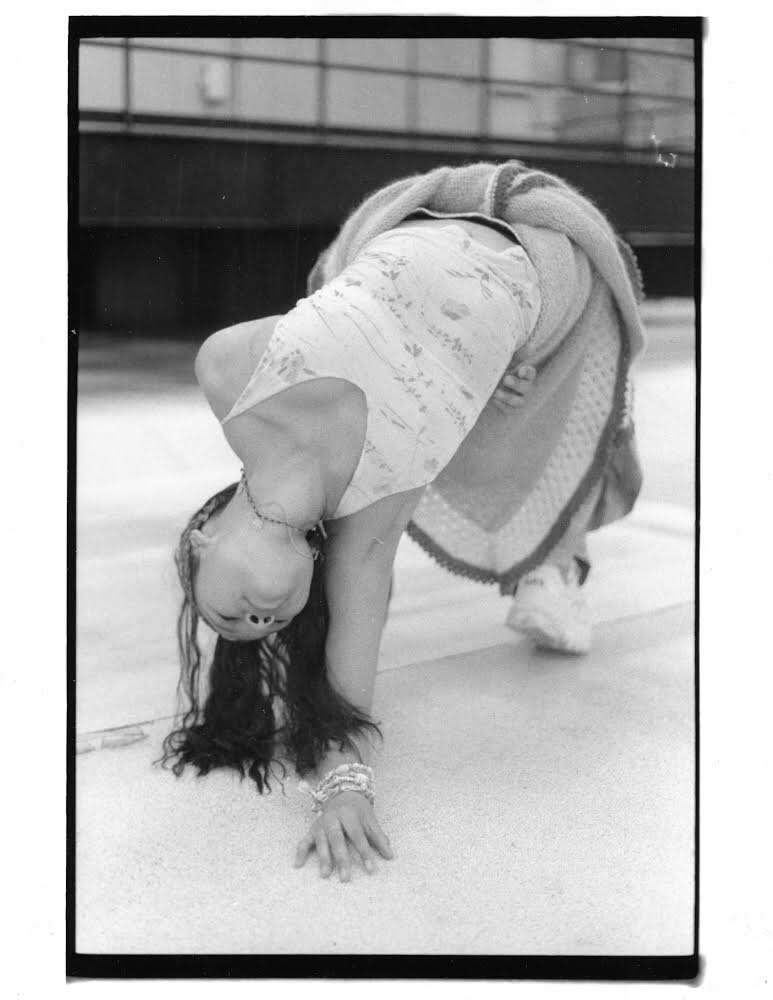

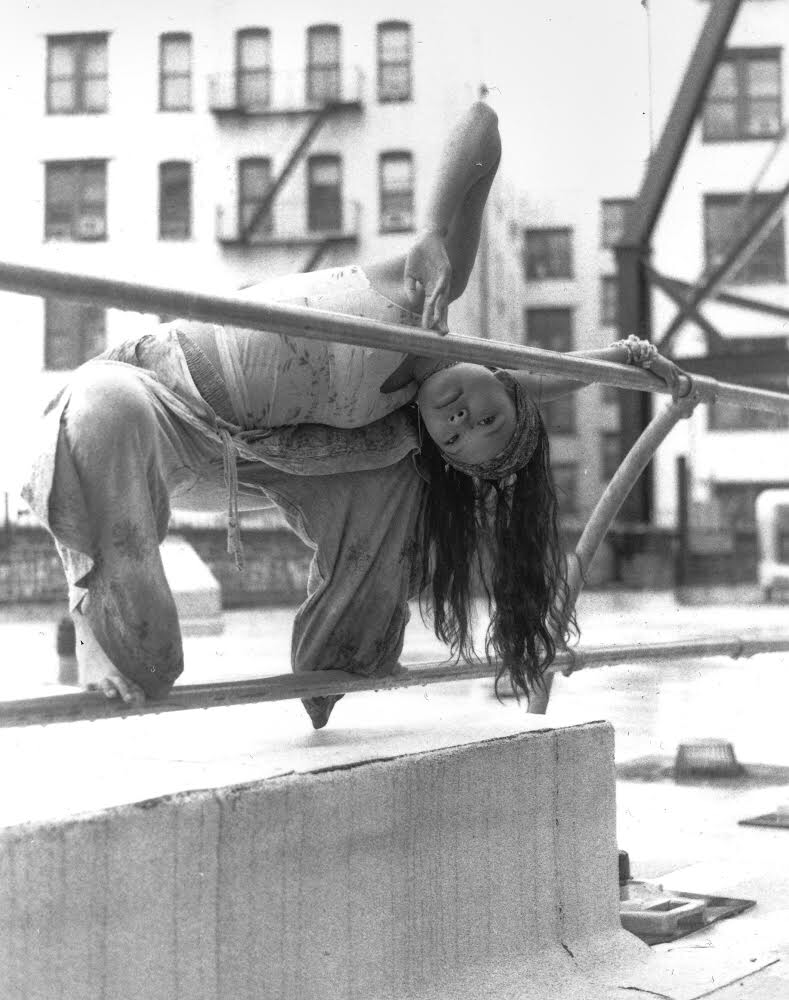

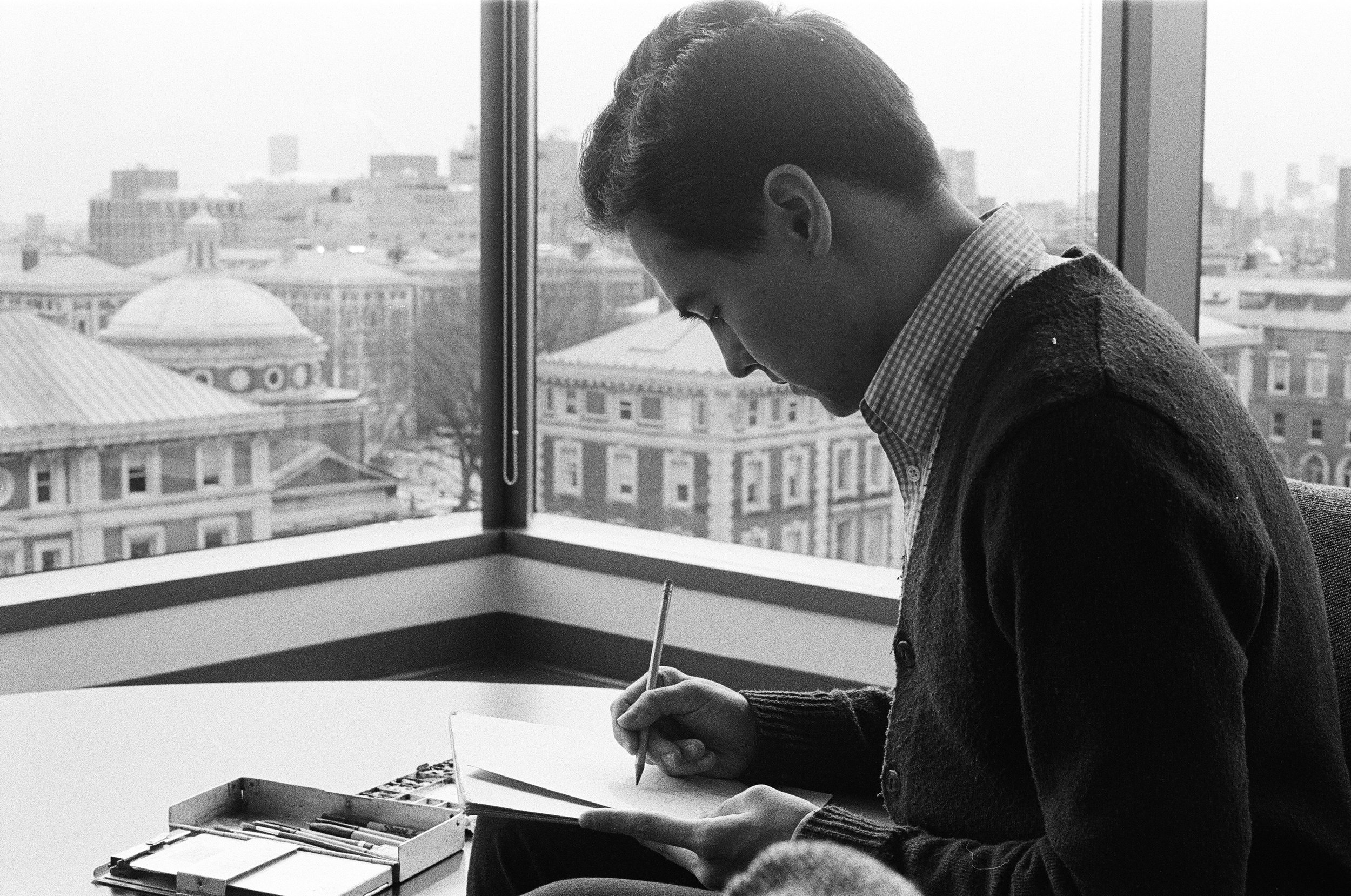

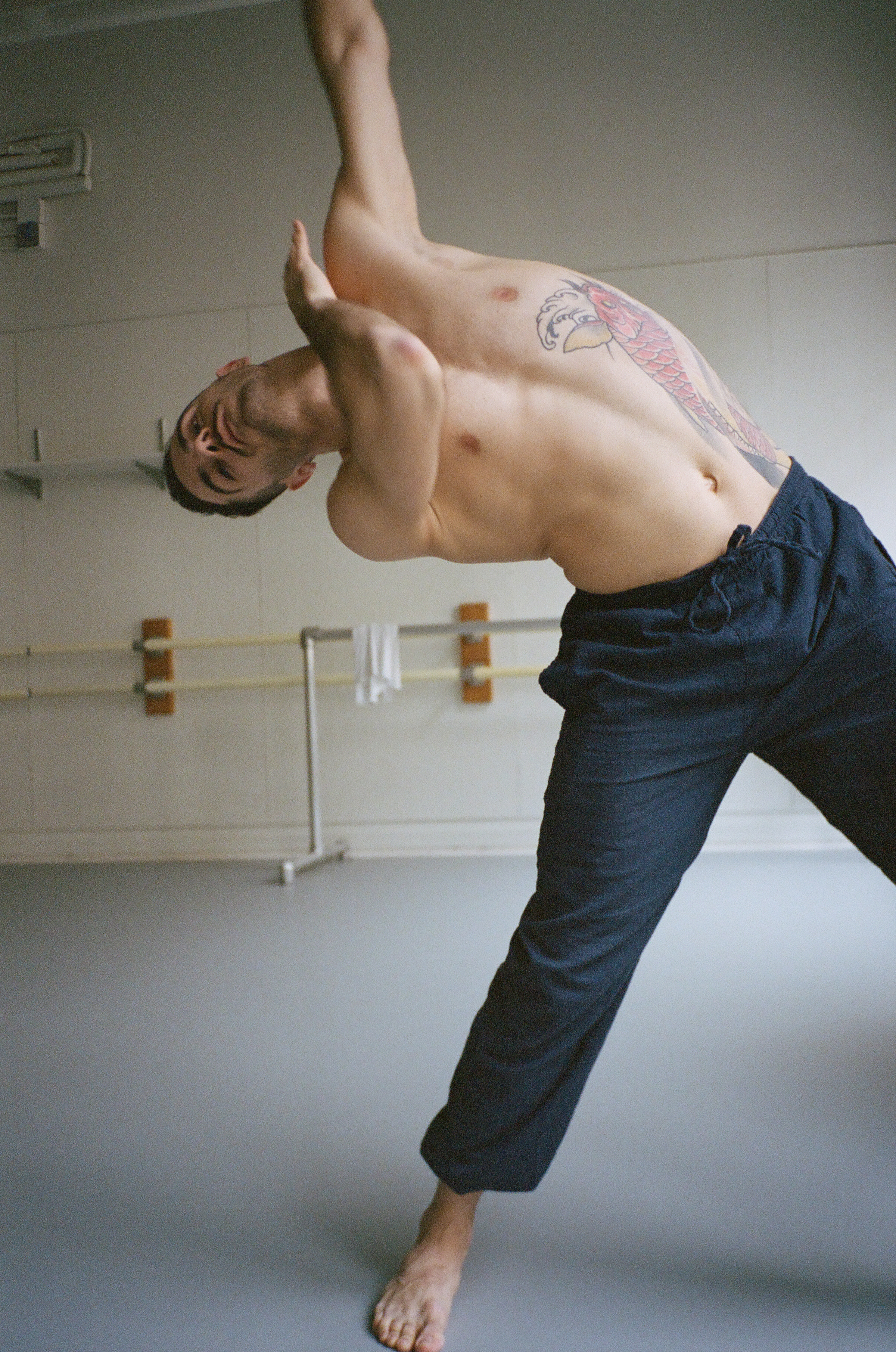

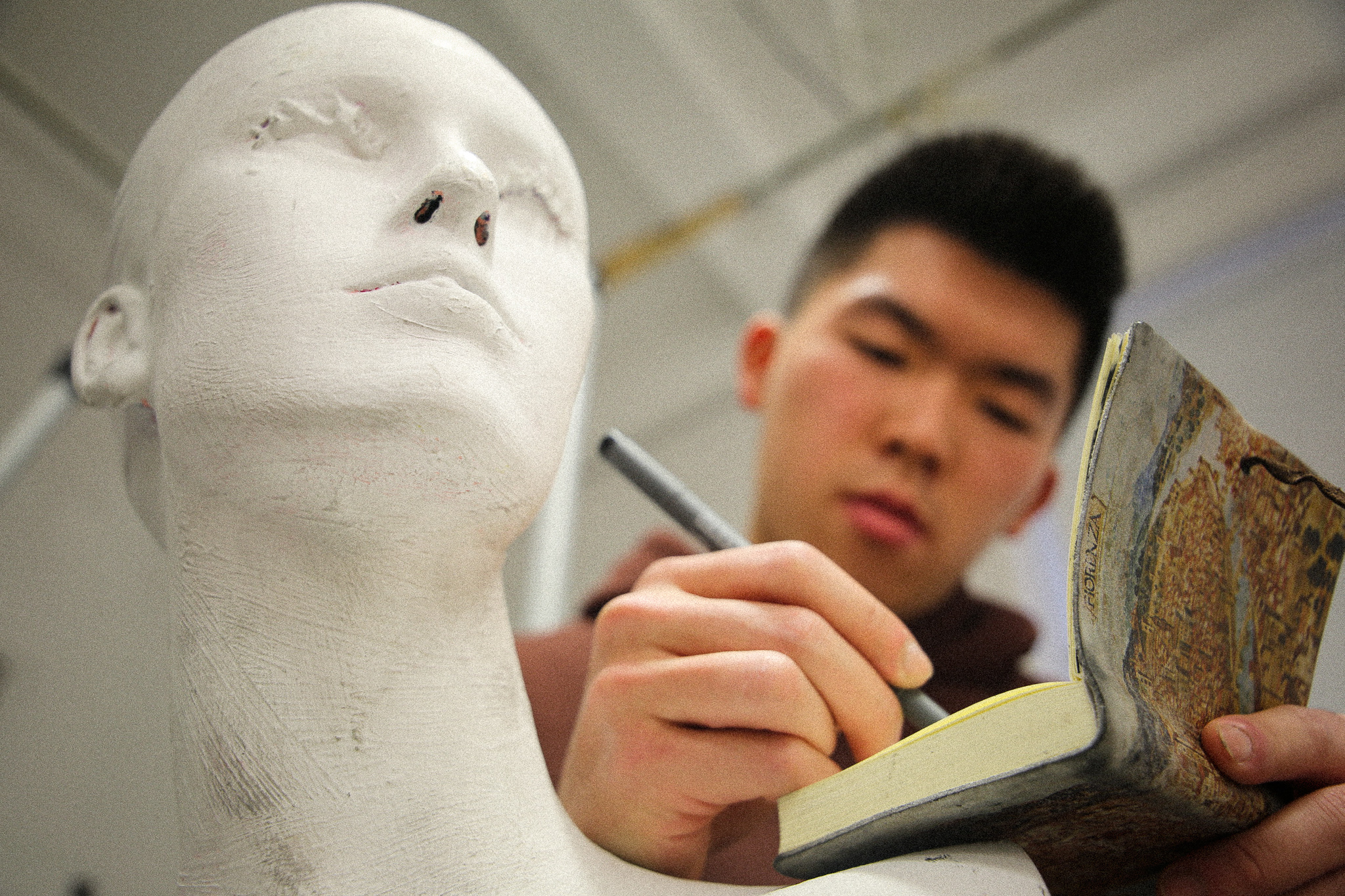

Can you explain the relationship between your hands and the clay? Compared to other mediums—like photo or like painting—there's obviously involvement with your body and your work.

I think your hands, in a lot of ways, are like the most powerful [part] of this medium. When you're throwing, when you're at the wheel, it's nice that it requires your absolute focus. It's nice that it makes you really present. You know, if your hands slip, the whole thing can flop over or get smushed. So you have to be very conscious about every microscopic hand movement, because the tiniest little bit of pressure could change the entire shape. It makes you really self-aware of your body in relation to the clay, and in relation to everything around you.

I really do like the idea of noticing, with absolute focus, your body, your hands, in relation to the clay and piece at work. When you're making your pieces, what do you have in mind in terms of style and inspiration?

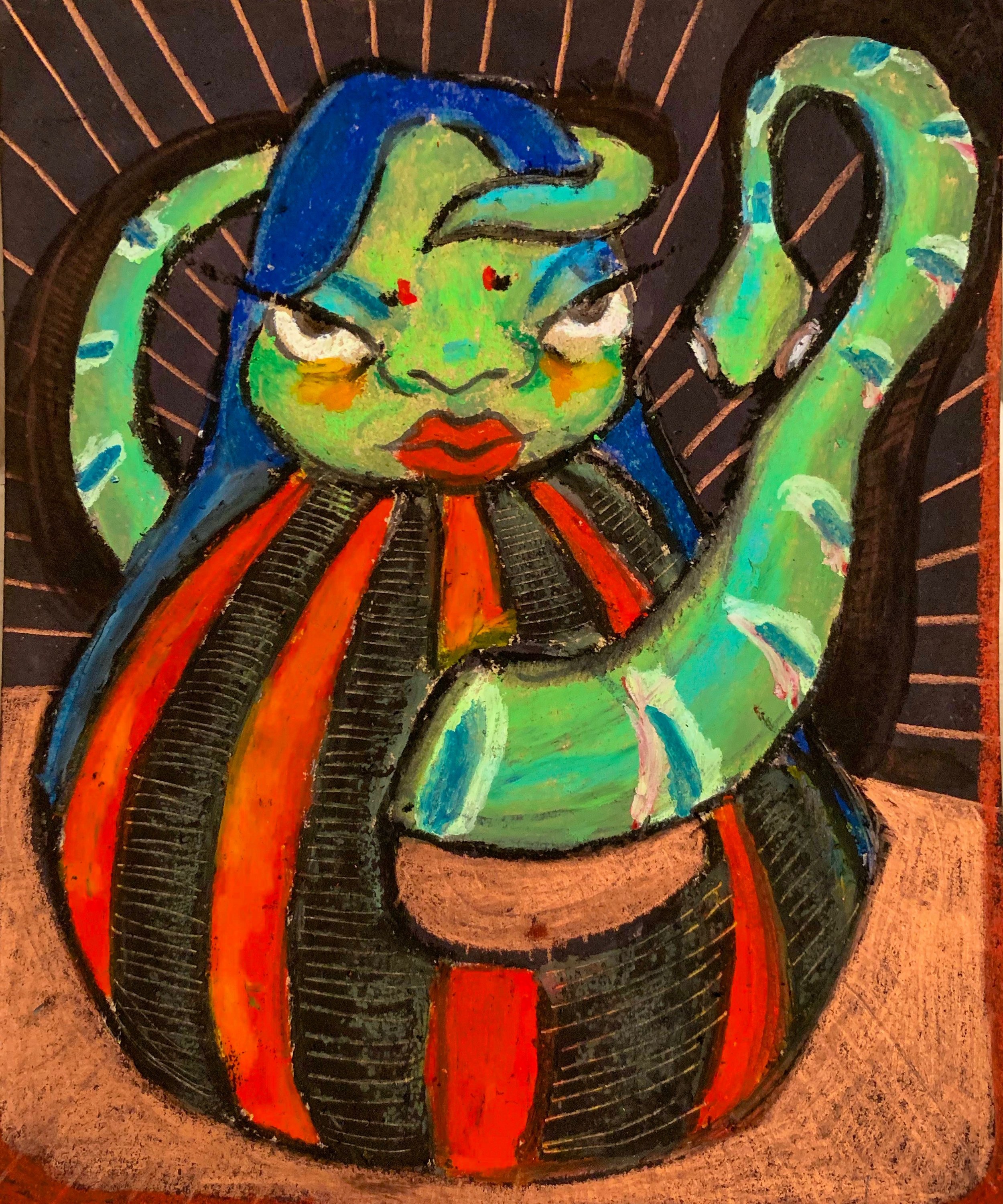

Working in ceramics brings out this childlike energy in me. It reminds me of days way back in art class—of just messing around but then creating something out of this frenzy. And I like to bring that childlike energy into the work. I like big, friendly looking forms, and a lot of really bright colors. A lot of vibrant glazes. When I'm making pieces, I like to think about what's going to make me happy, and what's going to make others happy. Whether it be sitting around the room, or used for meals—I really want to be able to use my pieces and to share them with others. For instance, I have an elephant teapot with flower designs that I love and use practically everyday.

What are you trying to convey to yourself and to those looking or using your work? Is there a story behind each piece?

A lot of the pieces I've been making lately—because I'm working at this studio near campus, where I also teach—have been made as examples or to show someone how to do something. So that's kind of exciting to me. I really enjoy working alongside people and using pieces as a tool for teaching. That's one of my favorite parts about the ceramics I'm doing right now, especially because I'm studying education. I like to use my art and the process as a way to possibly unlock new teaching methods, or to think more about hands-on learning. As for the story behind each piece, I think each piece just reminds me of the meticulous work that went [into it]. You can look at some of the handled pieces and you can see every carve, every line on the leaves—like on the teapot that I made. Or even think back to every single chemical you had to mix to get the right glaze mixture. It's just cool to look at a piece for which you have been so involved in the process. Everything from the glaze to the firing technique requires careful work. For example, some of the pieces that I do are roku, which means you take the piece out of the kiln when it's at the peak temperature, 1700 degrees. And the glaze is still molten. Then you put it in this trash can full of combustibles like leaves and newspapers, and you put your piece in the can and watch it burst into flames. When you take your piece out, it's got all of these weird markings from being exposed to the fire. So yes, I tend to look at my pieces and see the work, awareness, and the care that went into its making.

What's your favorite piece?

That's a good question. I have this one mug where the glaze just came out really unexpectedly. The interesting thing is when you combine glazes, you could have like a yellow and blue—and when you layer them together, instead of making green, the colors can make red just because the chemicals interact weirdly. That's one of the best parts for me, when you get this super random, unintentional color. On my mug I had a deep green, and this kind of reddish glaze over it. Where they met, there was this really bright turquoise color. So, it's just this mug with a huge turquoise spot at the bottom. And that's what I drink my coffee and tea out of every morning. That's my favorite—my green, red, turquoise spotted mug.

How has pottery and ceramics influenced your life? Everyday experiences?

I've been working with pottery and ceramics since high school. It's opened up a lot of job opportunities for me. Like this summer, I was teaching pottery in Washington State, and now I'm working at a studio. I would say these opportunities have really allowed me to see how my artistic interests and my education interests collide and collaborate with one another. More recently, they have really begun to inform each other. I feel like I'm learning a lot about teaching pottery that can be applied to other forms of teaching.

Absolutely! It's really interesting to see that translation. Could you give an example of where your art and teaching interact?

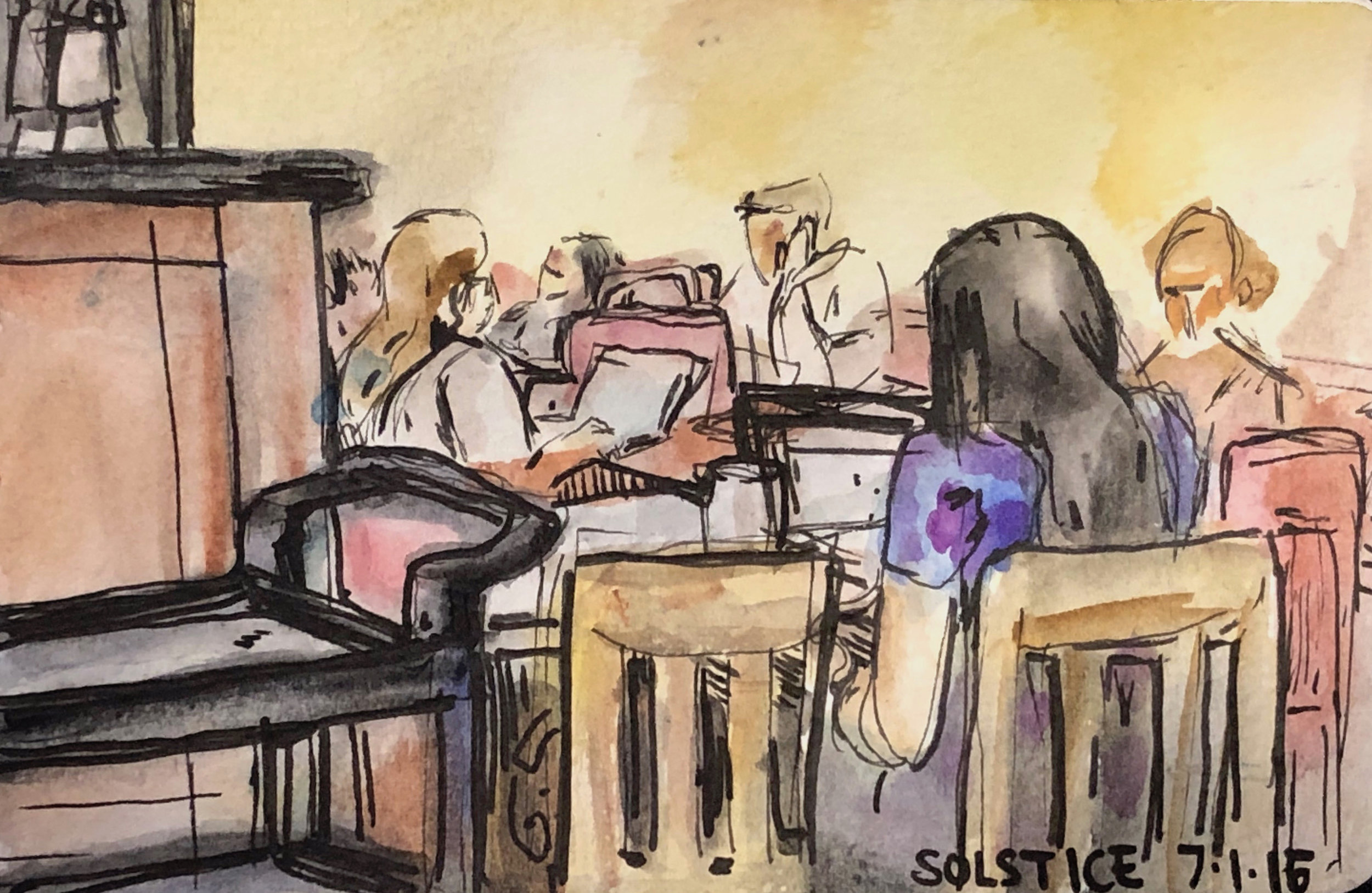

I teach the kids class at the studio, and some of them are very young. I'm learning that when you put this piece of clay in front of a child, they're not going to listen to anything that you have to say. All they're going to want to do is play [with] and squish the clay, and you really can't blame them. But that's part of the magic about the clay, you know? It's exciting to see sheer joy just because of a tiny piece of clay. I guess channeling that excitement about the task and clay at hand is something I feel like can apply to any arena of education, because you’re working with children and are helping them create something by the end of the class. And as I said earlier, creating a pottery piece is difficult, and requires careful attention to the work. It's amazing to see how the children's excitement for the clay is transformed to this sort of eager attention and focus.

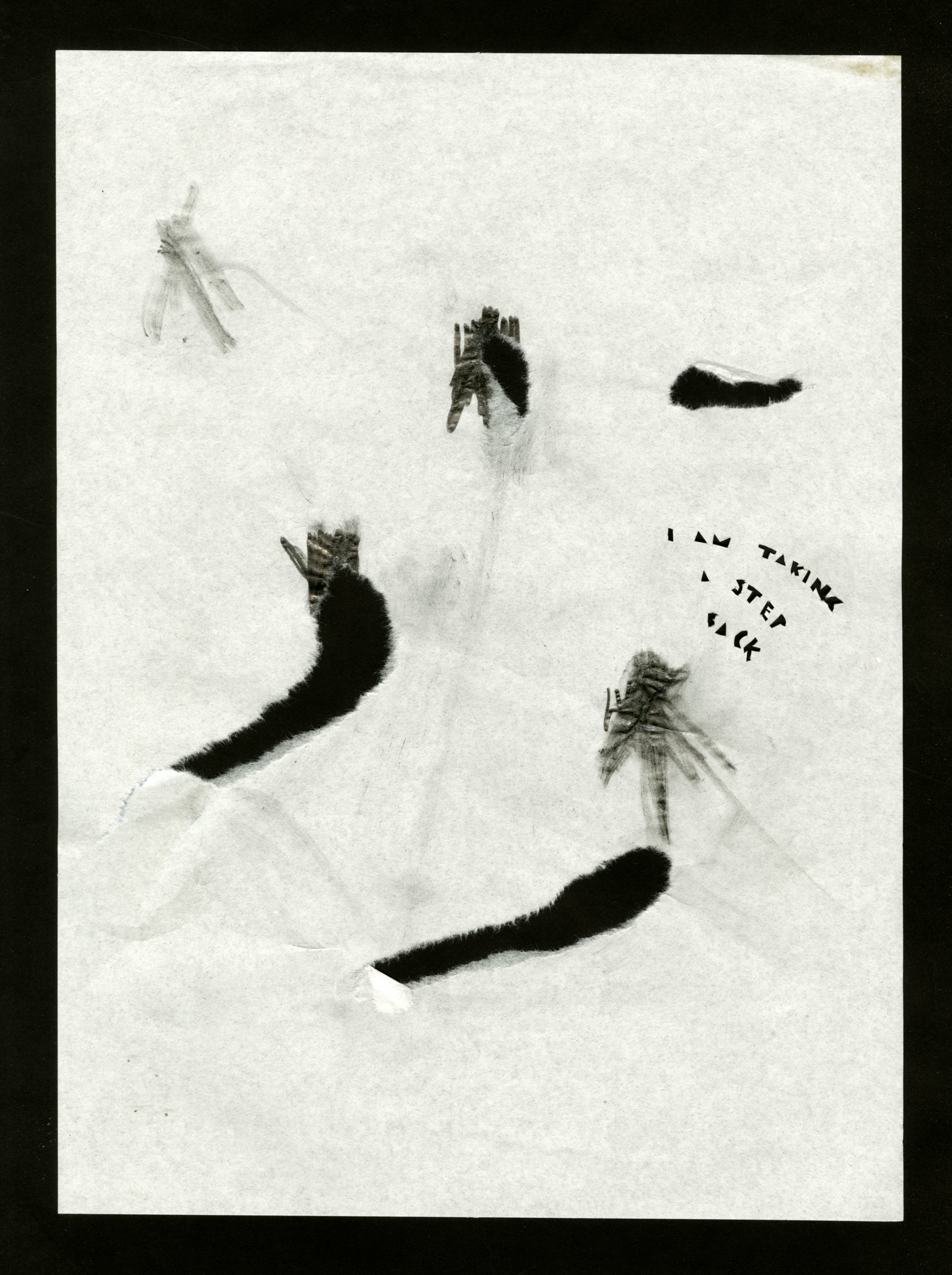

This idea of intimacy, whether it be your own work or teaching children, is integral to your process. Like you said, every step is important and has to be dealt with with awareness and attention. Could you elaborate more on the intimacy aspect?

Yes! Every step and every curve, every color that comes out in the blaze, every task you perform, every bit of work you put into your piece and its process, is an intimate kind of work. So at the end, I feel as if I become really tied to these pieces. Like it holds some part of myself. And especially in my case, I love using my pieces for the everyday. Being able to use and be in contact with your work further shows this intimacy. My pieces become part of my life. Intimacy lies there.

What was your favorite art class at Barnard or Columbia?

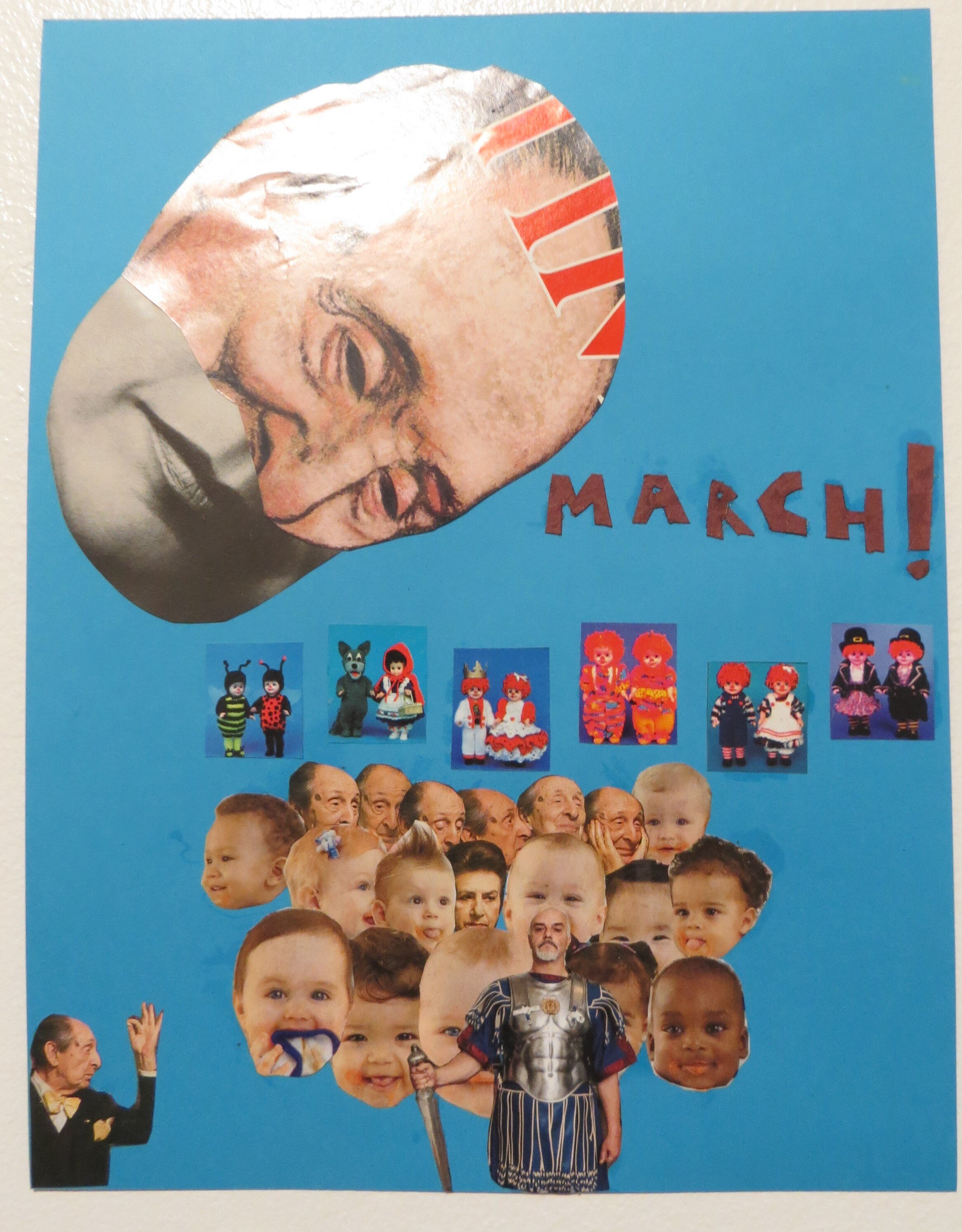

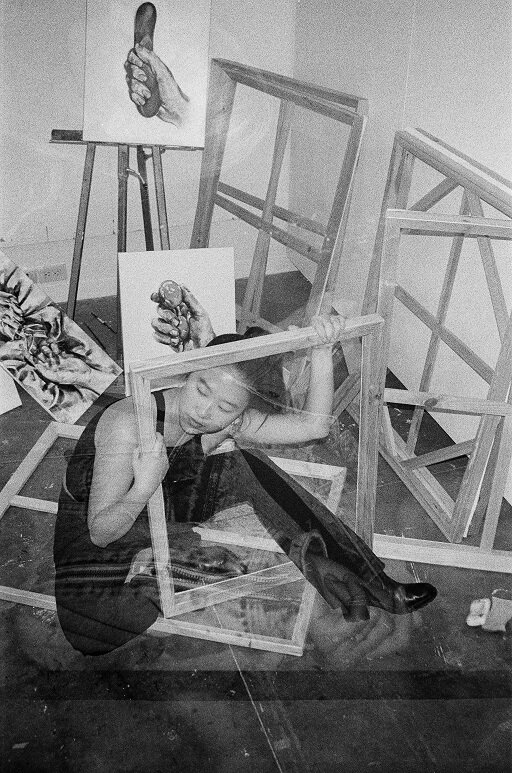

I've only taken one, actually, but I took Sculpture I freshman year with Kambui Olujimi and he was a really wonderful professor. I initially thought that we were going to be making little things out of clay, and that the class would be a sort of de-stressor. And it wasn't! It was one of the most stressful classes I've ever taken. We weren’t working with clay, we were working with metal. I literally learned how to weld!

Really? Oh my god!

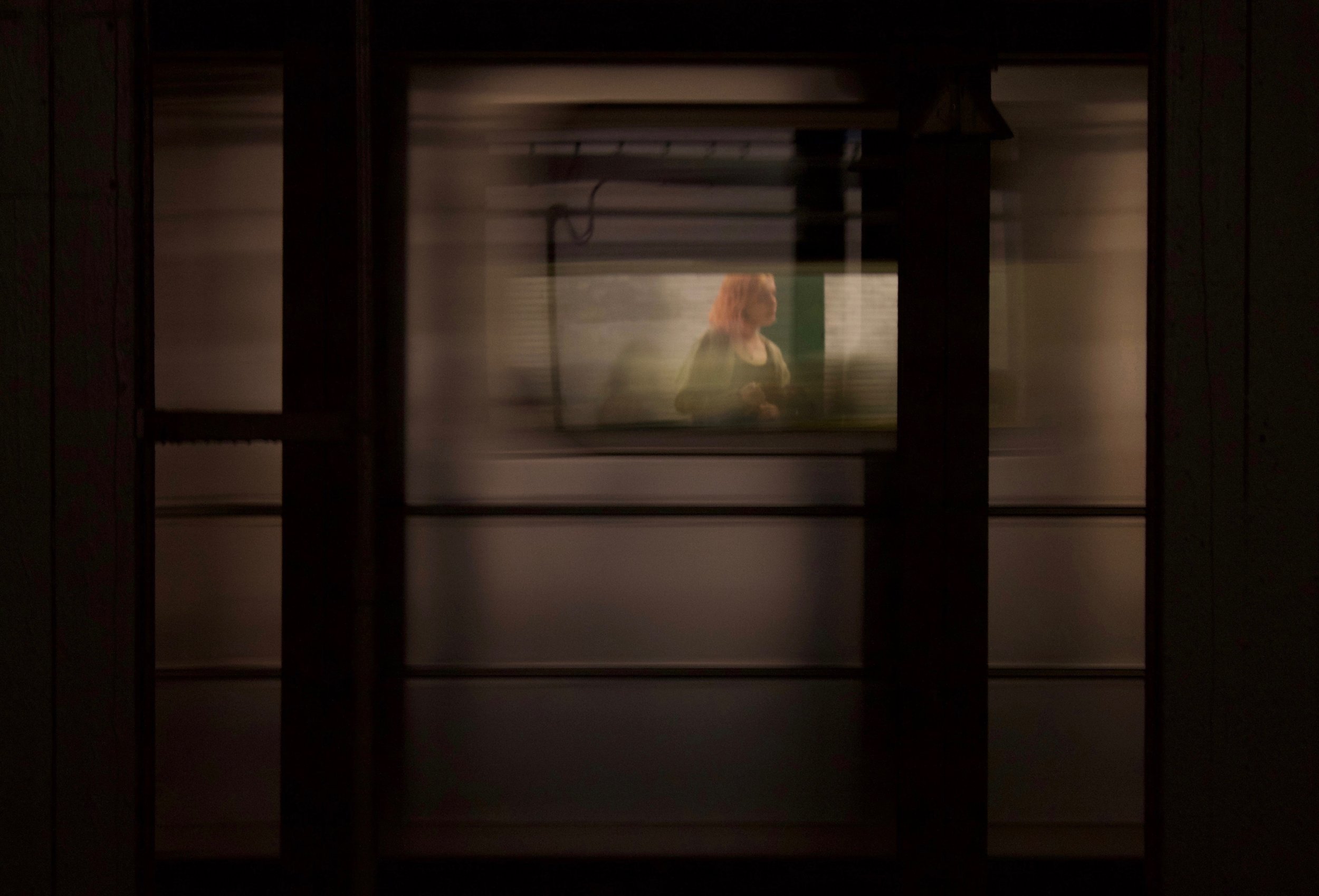

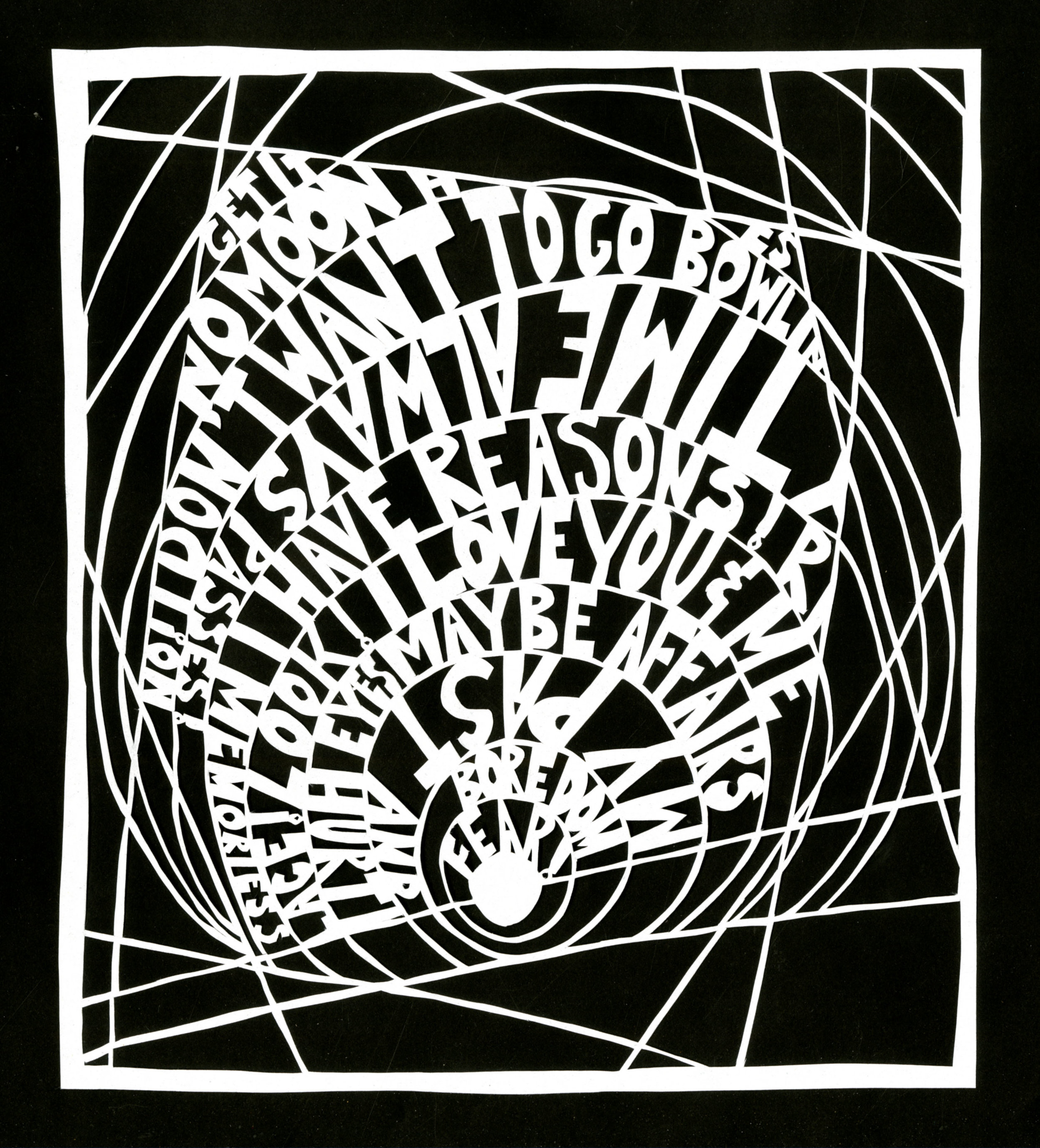

Yes, really! On the top floor of Prentis, they have these metal shops. You get these sheets of steel, your big mask, your plasma cutter, and you're just welding! Once for the class, I made this metal wall that had all of these windows that opened up. [For] some of the windows you'd be able to see through to the other side, while others had mirrors. If you saw one on the opposite side, it was like you were playing hide-and-seek, but sometimes you were only finding yourself. The assignment was to make a mask, and that wall was my mask. That class was so much more work than I thought it was going to be, but it was really worth it. It was fun and inspiring being surrounded by people that were also invested in making these really crazy structures and sculptures. Also, working with a professor who is doing art in the real world was amazing. It was such a fascinating class. I would take it again and again and again. To be completely honest, I think I spent more time working for that class than I have for any class since then.

What would be your ideal, dream piece? What would you make?

My ceramics teacher in high school, Bob, who wore Crocs and a kimono to class all of the time, always talked about this friend he had in Oregon who threw ceramic hot tubs that were completely massive. He said that his friend kept breaking his wrist—because when you're throwing that much clay, if you have your hand slightly at the wrong angle, it'll literally just snap. Which is crazy. Sometimes I dream about throwing or creating a piece that massive. Maybe I'll make a fountain, or just grand monuments, and place them in random locations. That would be a dream piece. A massive structure placed—gently, of course—in random places everywhere I go.