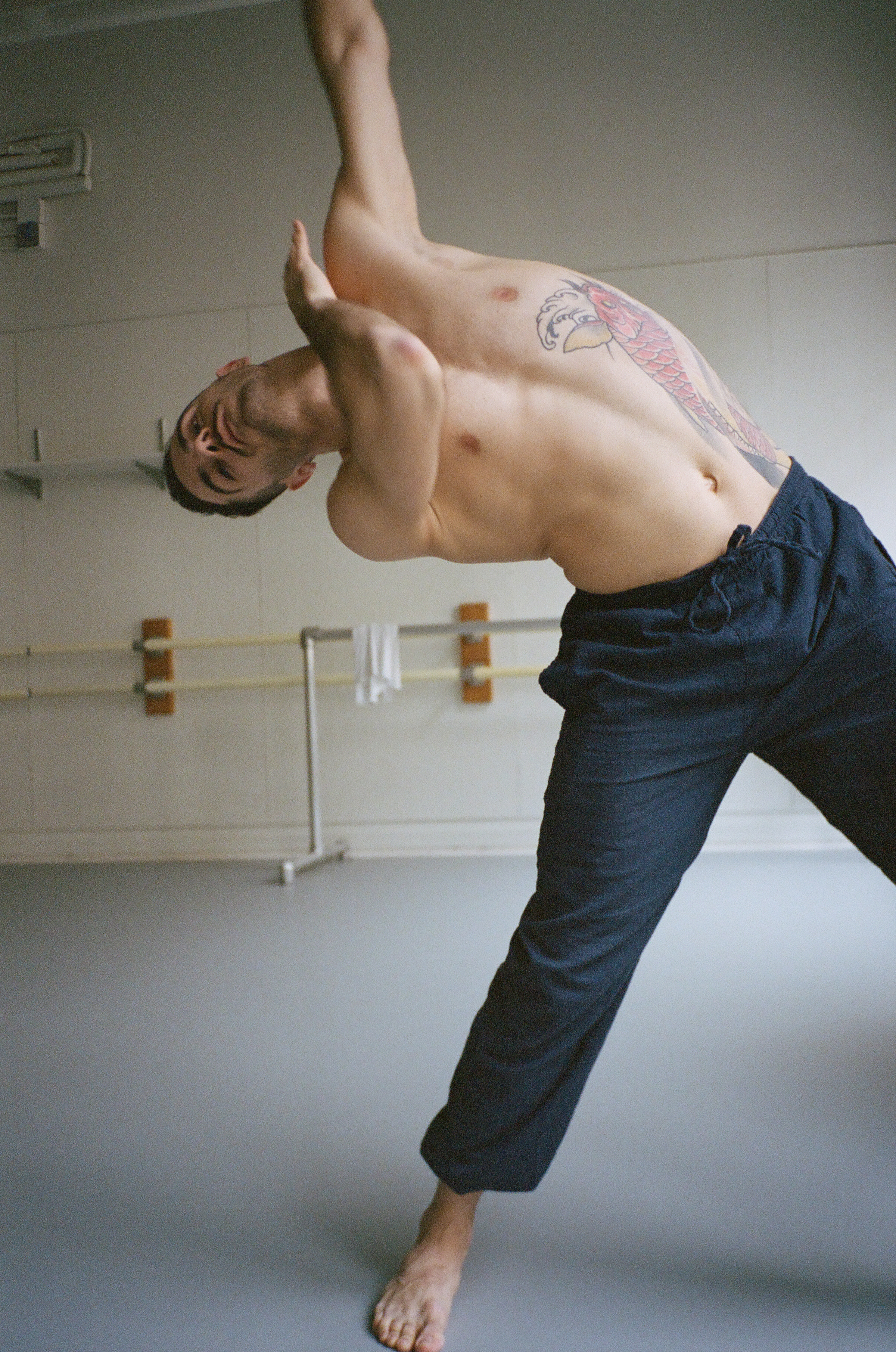

Photographed by Natalie Tischler

Interviewed by Zoe Sottile

Hi! Can you introduce yourself?

I’m Kosta Karakashyan. I am a senior in CC majoring in Dance, and I’m from Bulgaria. I’m half-Bulgarian, half-Armenian. I’ve been dancing since I was five.

What made you want to pursue dance?

When I was five, I had a girlfriend in kindergarten, and she was going to start dance lessons. My parents signed me up because of her, and then she never made it to the first class. But I went, and I liked it, so I stayed.

When I was in high school, I got an offer to join Dancing with the Stars in Vietnam as one of the pro dancers. I was 18 and had no clue what I was doing. I was the youngest ever pro on the show there. We had to work with a team to pick the music and choreograph and work with the lighting designer and that’s when I started liking this whole production side of [dance]. And now I’m not done with performing, but I’m more interested in creating something on stage that other people with more virtuosic bodies can express.

What was the first piece of art that really inspired you?

The thing that I respond most to is books and reading and storytelling. A lot of the dance work I do now is more narrative-based. Of course, I loved Harry Potter like everyone. I think I was the same age as Harry Potter when the books were coming out. There was this contest -- I made a clay dementor, and I sent it in, and I won a free book. That’s one of the first things I made. I was maybe 13.

What are some artists or creators that inspire you?

In terms of film, I love Baz Luhrmann. He has a reputation that he meddles in every department of his productions, and it produces a very clear visual style in his work.

Is that similar to how you work?

Yeah, I like to give my collaborators a lot of freedom but then at the end I want to shape the edges of everything so it fits the story we’re going for. There’s an Israeli choreographer that I’m super obsessed with right now. Her name is Sharon Eyal and she makes these really alien, weird, sensual, sexy, tortured movements. I just did a review of one of her pieces. I like a lot of disparate elements from different people. I think nothing is original. So I like to draw inspiration from a lot of old things and a lot of new things. Music is always a big inspiration. I like a lot of classical composers like Erik Satie.

Can you speak about the senior thesis you’re working on?

It’s a solo, but I ended up involving a lot of people. Allison Costa and I are the inaugural student artists-in-residence at the Movement Lab at Barnard. I’m using the space to develop the thesis. I want to make a piece that’s about the anxiety and the stress that we collectively face on campus, because I think dance is a good medium for sticking it into the audience’s heart a little more than just reading about it. You can feel it more when you see something visceral on stage. Movement-wise, it’s a contemporary flamenco fusion. I’m working with the flamenco professor at Barnard, Melinda Marquez. Guy DeLancey, the technical director of the Movement Lab and LaJuné, the current artist-in-residence are working with me on creating lighting that responds to my heartbeat in real time on stage. I am working with Antoine Assayas, a composer from France who I met on Instagram, and I’m trying to get another costume person -- it has all these moving parts.

Why does stress culture figure so prominently in your work?

Last semester I was reflecting and thinking about my art practice, and I realized that everything I’ve made or everything I’m planning to make revolves around anxiety. I realized this is clearly getting to me and I need to externalize it in some way. So I choreographed a piece for the Columbia Ballet Collaborative about four friends who are there for each other, but then get whisked away in their own problems. One of them has a breakdown. It jolts the others out of their own things to come together and lift her up. I think there’s a power to acknowledging [anxiety] and reclaiming it and being okay with knowing how that feels instead of trying to convince yourself that everything is fine. Of course Columbia as an institution needs to do a lot more, but the things we can control are our reactions; I’m interested in making things that give back some agency to people.

How is dance different from other media, like film and writing, that you work in?

The most important thing about a dance is a title, because that’s the one place where you can guide the audience. It’s always overlooked. I think context is really important. When I approach making art, I don’t necessarily like to be vague or confusing just for the sake of it. I like art that will take you with it so that it doesn’t exclude the audience. Dance is already a little bit underappreciated, and I think it’s because people feel scared that they don’t “get” it. You can do service to your audience and present it in a way that’s understandable.

One of your interdisciplinary projects is the music video for “Drips” by Acrilics, in which you worked both as a choreographer, director, and editor. How did that project come to be?

The way that video came to be was quite random. A friend of mine -- who I haven’t talked to in years -- randomly reached out to me and said, ‘I saw you’re directing things; do you want to make a music video for me and my friend?’ And I said, ‘yeah, sure.’ It was the Sunday before finals. I grabbed all of my class’s dance majors. It was very last minute. I found the director of photography, Xuelong Mu. I’d never worked with him, but he was down. We rented a camera, we found a makeup artist, I went to H&M at Times Square. I always style people from there because it’s open till 1 am. So I went at midnight the night before, got a bunch of clothes, and then we just made everything happen on the set. We had six hours in Diana. It was something out of nothing. The girls were so good. I had prompts or ideas for them but they improvised everything on set and they looked great.

How do you navigate between dance films like that project and live performances?

For me, if I use film for a project, it’s usually because I want it to be more shareable with people. I think film is good for sending a message or making something that serves a specific purpose.

For stage I work really collaboratively. I want to make sure that everyone who’s going to be performing it feels really comfortable with the material and that they feel invested in it. If it’s film I control a little bit more. I have a clear vision in my head; it’s more detail-oriented in a way.

You also created a film about the LGBTQ+ persecution in Chechnya, “Waiting for Color”. What inspired that piece?

I remember when news first started coming out about the situation in Chechnya, it was so horrible and I wanted to do something about it. So I joined the activist group here in NY, Voices for Chechnya, but I also wanted to make something that confronts people with the situation. It’s based on these 33 anonymous stories of people who were tortured and then released. It’s from a report published by the Russian LGBT Network. [The film has] gotten a pretty amazing reach. In the U.S. it was featured by GLAAD and by Conde Nast. Now I’m presenting it at Short Waves, a festival in Poland, in March. I did a presentation in my home country [Bulgaria], which is still pretty homophobic, but surprisingly the media was really into it. I ended up doing seven interviews in five days. Sadly, it’s still relevant: now, there’s a new wave of violence. I think now my next projects are going to be in that social realm as well.

How does it feel to speak to such a large platform?

It feels like the more and more I talk about it the more energized I get. It’s a really tough topic. Now when I watch the film I feel so distant from it. I can’t believe I actually made that. I edited it and have watched it so many times that I can’t objectively look at it anymore. I just know it’s out there. It’s not necessarily easy to talk about, but I know that publicity brings awareness to the situation. I’m thankful to be able to bring more light to what’s going on there and hopefully it helps in some way.

What is your experience like as a “working artist”?

My plans now after graduation are to move back to Europe, where there’s a lot more state funding [for art]. In New York it’s really disheartening to see successful people who already have a career still barely scraping together budgets and things. It’s a really sad reality. I don’t like that the expectation that you should love your art so much that you should have a shitty lifestyle to do it. Of course, it’s not easy everywhere. But there are places that are more accepting and more supportive.