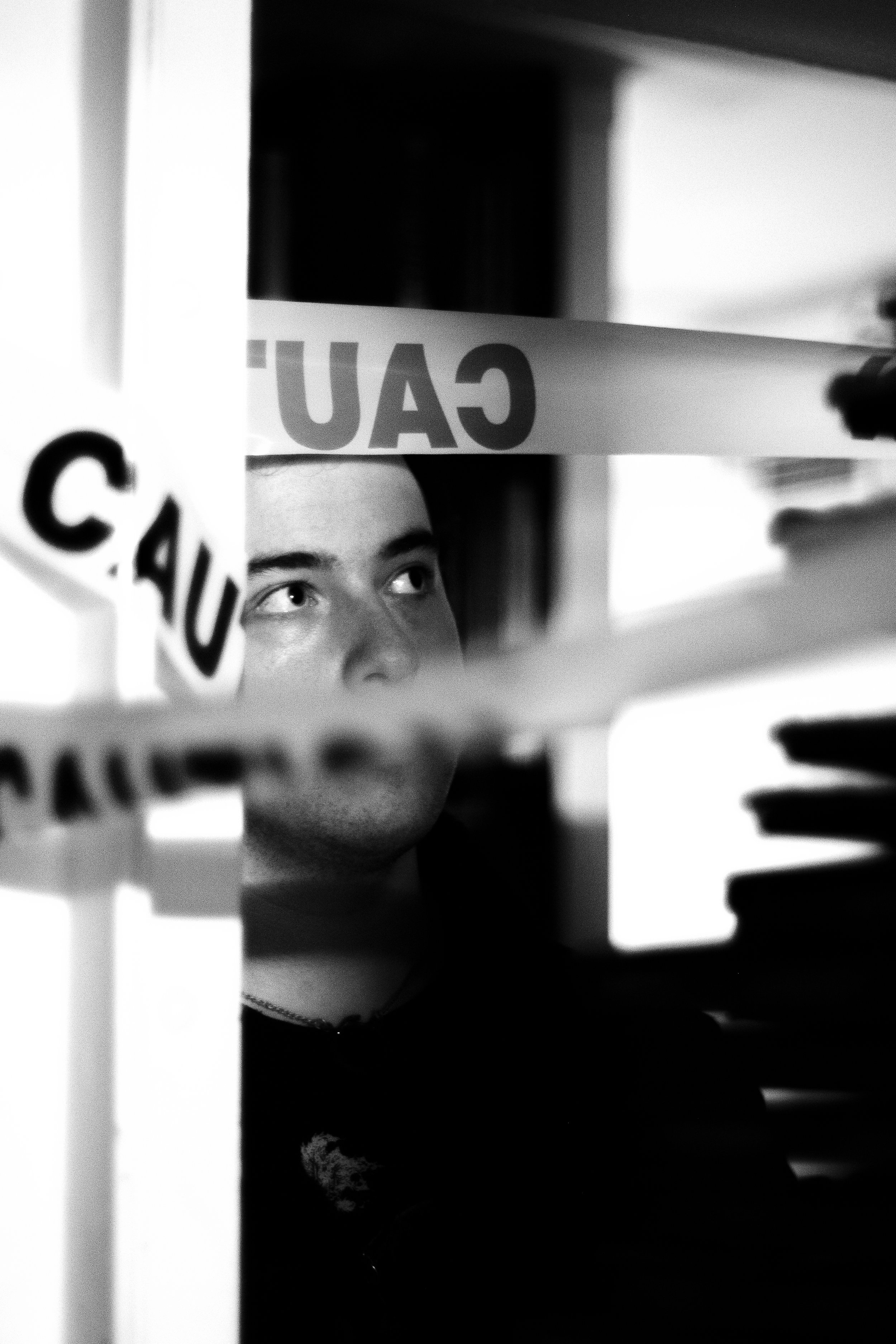

Taelor Scott in conversation with Yosan Alemu

Photographs by Cameron Downey

Taelor Scott is a senior at Barnard College, studying anthropology. Her artistic focus centers on photography, film, and visual arts more generally as they relate to culture and its respective production.

YA: What is your photo making process like? What feelings do you get when looking at an image?

TS: That's [a] good one. I think that I started making photos, or rather, the reason why I wanted to start making photos is because I would see images and would think to myself, “This needs to be captured.” But also, I would see these same images, and felt as if something was missing, as if other images and stories were missing. There are a lot of people who I live around who I didn’t see represented in photography that I admired. And it occurred to me, that if I wasn’t going to see these images created by others, I would have to start making photos myself. What else was I to do?

I started by taking obnoxious pictures of my family all of the time—taking and taking and taking pictures. In retrospect, despite my early picture-taking habits being fairly annoying and in-your-face, taking pictures of people I cared about, like my family, helped me develop a sense of caring and intimacy when taking pictures of strangers, or people I have hardly talked to. It’s really quite hard to take a picture of someone [you don’t know] and portray it as if they are someone you deeply care about; and capturing that sweet spot of care, of loving someone without knowing them, has become so integral to my work now. Every time I take a picture I want [to] also create a story for that subject in the frame.

YA: Combing back to your last note on creating a story for every subject you capture; what is the narrative you are trying to tell? Is it a humanizing process?

TS: Storytelling has been one of my biggest interests since I was very small, and I found that I could combine my passions with visual art, like drawing (but it didn’t take me long to figure out that I could not draw for the life of me). With photo work, the camera, for me, helped me capture and create images that were always stuck in my head. Using the camera has been an ongoing learning process, and I really admire the discipline that comes with it. There is always so much more to learn. I don’t know everything there is to know about digital photography, or analog, or large format. I rather enjoy my position as a student of photography, because I always get to be learning, improving, and changing.

YA: Student of photography, rather than photographer—I like that. And so, when you create images, how do you want people to feel or react when viewing them? Is there an affective response to your work that you're trying to capture? Are you trying to create a dialogue with your visual work?

TS: When I’m taking a picture of someone, it usually involves a sort of conversation between me and them, because in that conversation I’m trying to find a little piece of them that I can capture within the inner workings of the image. In taking a good image of someone, you do end up capturing a little piece of them. And even if you’re taking pictures that don’t involve people, you still have to work to create or find that moment that makes the image feel special, makes the photographer, subject, and viewer feel close and connected.

For me, when I’m sitting down, selecting and editing my shots, I am always consciously choosing the photos that display the humanity of the people within them. So that, even if I don’t necessarily know the person in the photo, I still feel like I do know them, am connected to them by this simple photograph.

YA: Do you ever create images that will intentionally make the viewer feel uneasy or uncomfortable?

TS: You know, I’ve actually been thinking a lot about uneasiness and of the different registers of response that are created in an image. I always try to keep the audience in mind when I’m making photos, but I think my next project will solely be about the audience. How can I make them feel certain things, react in a certain way?

Right now, the project I’m working on deals with me finding all of the boys I’ve had crushes on since I was four years old. Basically, I find them, and we tell each other our experiences of love and infatuation. So with this project, I’m not concerned with the audience, but rather, I’m concerned with myself and the subjects. In a way, this project is asking myself and the subject to get uncomfortable and uneasy. I really do think there is something amazing in trying to understand someone’s discomfort, and trying to capture those moments. It’s like being disoriented from yourself in order to really understand or comprehend the image or moment at all.

YA: You’ve mentioned finding instances that matter to you most, or instances that can be developed to have meaning. Who are your biggest inspirations when it comes to photography and what are you inspired by?

TS: My Biggest inspiration—so much packed in that. Helen Levitt, Gordon Parks, Roy DeCarava. Oh god, DeCarava. There was this copy of “the sweet flypaper of life” that I first saw in a bookstore, and I was completely speechless. I also feel as if the youth art community here in New York can be very exclusive at times, and I’m really appreciative that I’ve been able to find some older mentors who have taught me quite literally everything I know, especially artistic integrity.

For instance, Patrice Helmer graduated from the MFA program here, in photography, and she has taught me so much. Knowing people like you, or are around your age in close proximity is so meaningful when it comes to tending to your craft. And even more so, knowing and being influenced by people that are close to you, in my opinion, makes making art all the better.

Like right now, I’m really interested by the notion of girlhood, of my own girlhood, and of others around me. Flushing out this interest has brought be back to my days as a sixteen and seventeen year old where everything around me felt impossible and possible all at once—typical teen angst. But I so clearly remember being that anxious and awkward teenager, and having the camera be a direct extension of how I could see and make sense of the world.

I’m also working with the Black Motherhood Project, and in our work, I’ve really been confronted by the idea that as black girls you are either being looked at, or you are being ignored, [or] made to be invisible. And for me, when I’m shooting, I am always trying to find the moments where I can make these black girls feel seen, not necessarily being looked at, but seen.

YA: This is a great segway into the next question. I’ve noticed that a lot of your work deals with moments of intimacy and care, of liminality, space and instances of waiting. What do they mean to you? Why are they important to you and your work?

TS: I actually have a good answer for this one. The spaces of liminality and waiting are two concepts that have become very important to me, because I used to see them as somewhere I was trying to get to. I didn’t like being in moments of waiting or spaces of insecurity and unknowing, of things not being at the right time. But the spaces of liminality and waiting is where the living and the inspiration for living comes from. That when you’re at an impasse: you really have to appreciate being stuck; or maybe not appreciate, but come to terms with that stuckness as a means of understanding and living through being stuck.

YA: So perhaps in the acknowledging of being stuck and in impasse, that can create for the potentiality to move, to escape?

TS: Maybe. But also, I think that even when you are in an impasse, you are still moving. That your thinking and imagining can become a form of movement. It might be slow, but you’re still moving!

YA: Still moving while being stuck reminds me of Lauren Berlant’s understanding of the precarious present, and her own theorizations of impasse. Does your academic background in anthropology influence your work? Do you think of photography and imaging as an academic practice?

TS: I’ve actually written my thesis about a combination of photography and anthropology, and I think the starting point for my interest in taking pictures is related to my interest in the ethnographic, in that I talk to my subjects a lot even when I don’t know them very well. To me, when I’m taking someone’s picture, it’s like creating a mini ethnography.

And I do think I look at photographs somewhat academically because academics has really influenced my desire to be hyper-ethical in the work that I produce; because at the end of the day, if you’re only making images that benefit you at the expense of someone or something, that is simply wrong, and very cheap. Also, the idea of radical sameness is very important to me and my photographs, of trying to capture the moments that are universal.

YA: Radical sameness as opposed to radical difference?

TS: Yes. Radical sameness in that I’m always trying to capture moments that are universal, where people can connect to my images, even if they do not know who I am, or who the subject is.

YA: So you’re graduating! How was the Columbia/Barnard art scene experience? Would you change anything, would you have wanted things to be different?

TS: So Controversial! Well, I do have a lot of thoughts. I would say I am grateful for Columbia’s darkroom—it’s incredible. I’m also grateful for learning and refining my photography practice at Columbia. I’m very much convinced every sixth grader should learn how to process and make photos, because it requires so much patience. When you’re in the darkroom developing your images, any small mishap and an image can totally be ruined, so patience and care are essential to the work being done. And at the end, the image, and all of the labor that was done in achieving it, becomes so meaningful.

YA: Every sixth grader! Okay, last question. Give me three words you want for the future, or the world, or even new worlds to look like. Just three words.

TS: Contextualized, illuminated, and responsible.