Feature by Alex Avgust

Photos by Gabi Levy

“Queer, feminist, post-internet, new media, lens based, collage, social media, attention economy, mental health. All the buzzwords.” Em Sieler tells me these are the terms they used to describe their work during a class exercise. I met Em in their cozy apartment one late evening, and after commiserating about the hectic nature of being an art student at Columbia, we started talking about the central tensions in their work. Their photography inquires into online spaces and social media, exploring the interactions between the individual and their digital presence. Their work is particularly concerned with the role they themself play in the attention economy as an artist and an image maker.

Em creates with the awareness that most images are made for advertising purposes. “Ever since the pandemic, I’ve spent all this time on social media being bombarded with ads,” they say, describing the way they noticed commercial images selling and conflating products with identity. As consumers, we are continuously prompted to reexamine what we are wearing and what sort of people we are in the same breath, something not even counter-culture is free from: “Nozw there is the idea of being a queer Brooklyn raver person, there is influencers for that and there is brands trying to align themselves with you and be like ‘wear this brand of underwear because you’re a cool Brooklyn person.’ ” In this whirlpool of visual commodification, they base their image-making practice on the notion that “Images are not just objective, they are not just there. They are selling something to us, so I want to be conscious of what I am producing.”

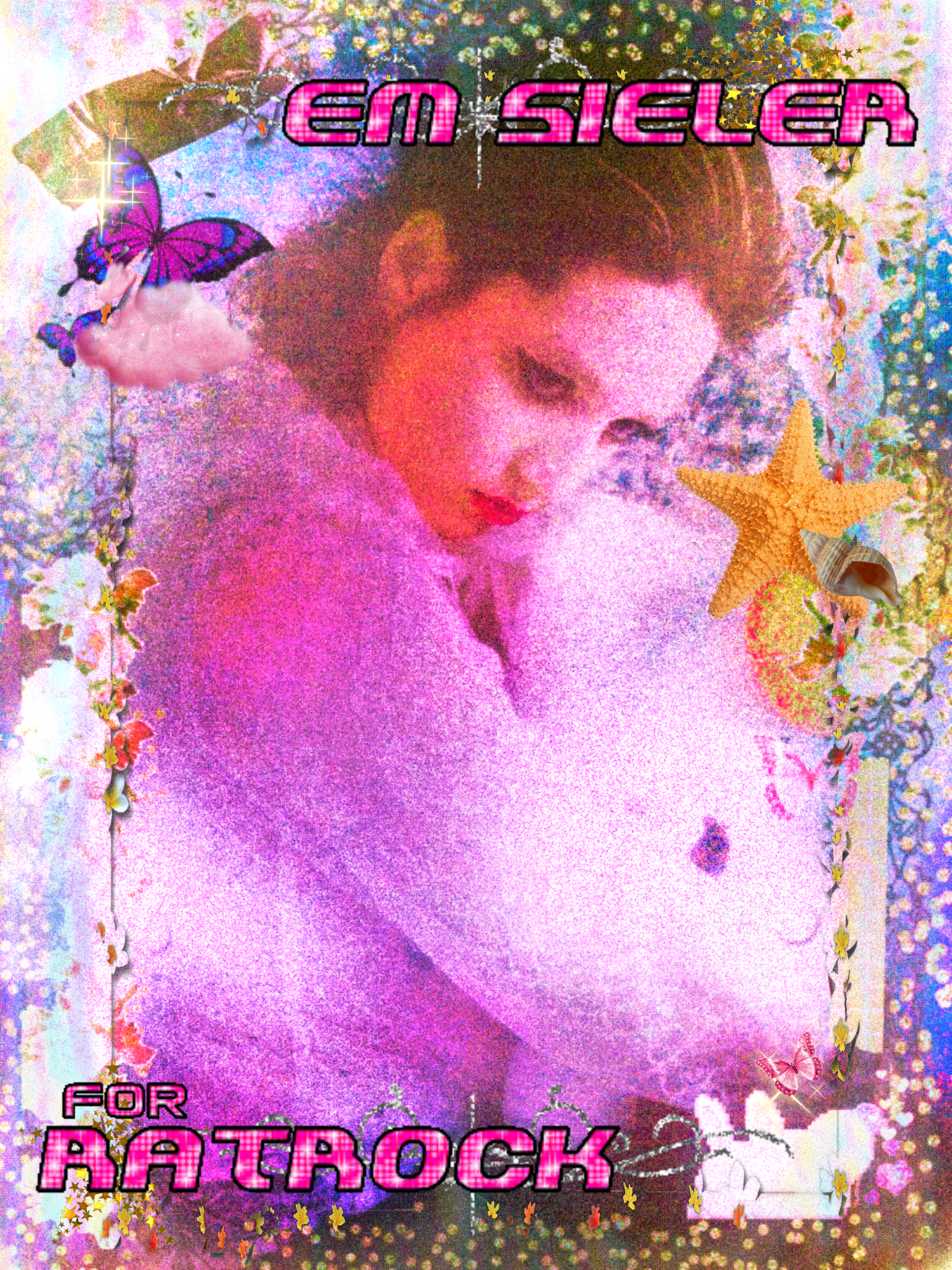

Much of Em’s work utilizes themself as a subject, tapping into the themes of self-image, self-portraiture and self-reproduction. “I would like to control the way my image is shown and consumed,” Em tells me, opening up about the way they have experienced their images being circulated and sexualized without their consent. “My body and sexuality sometimes feel out of my control, especially when I am in public. It’s something that people feel free to comment on,” Em pauses, “for some god-damn reason.”

Their work is about “controlling how my image is put out… and not letting somebody else take me and make something of me. I’ll sexualize myself before someone else can do it, and I’ll do it in a way I wanna do it!”

Love

Em is also interested in helping others reclaim their image in a way that feels comfortable and affirming. “I’m happy to be the queer, female-whatever photographer, cause there are a lot of creepy ass male photographers out there” they explain. Em expresses a tension between their own vision and commercial projects in this regard, balancing between the way things are “supposed to look” and what they wish to portray and evoke.

When they are not taking self portraits, they mostly collaborate with friends: “Before COVID, I was mostly going out with friends, dressing up, and taking pictures of them just doing whatever crazy stuff that we did. And you know, just being young and depressed.” Em describes. They want their work to portray a sense of intimacy, rather than appear staged or manufactured as they are also thinking about photography as a means to construct one’s identity on social media. “The whole thing of ‘this is my image on social media, I’m doing great’: I didn’t want it to be like that, I wanted it to be real—whatever that meant. A lot of me and my friends were dealing with mental illness at the time. As we still are; as many people are.” Authenticity is integral both to Em’s self-portraiture as well as their collaborative projects, their work connecting to its audience through the quotidian intimacy it evokes. It’s easy to image one’s self as simply another one of their friends, tagging along just outside the frame.

When preparing for shoots, Em focuses on grounding themself in the emotions the work is capturing. “Getting into the body and out of the brain, as an anxious, mentally ill person, is important to me. That’s the place where I can get into my art the most and not think about it. It’s a release, that’s when it feels the most real.” They center both their art and themselves in the moment, prioritizing active––as well as physical––participation, stepping away from compulsive forethought. “I’m participating in the moment, not really thinking about what I’m going to do, what I’m going to say, what this is going to say but I’m just being in the moment with the person that I have a relationship with.” Em’s work heavily emphasizes the proximity between photographer and subject, giving the product an incredibly intimate tone. They describe their process as very intuitive, as they largely work on short term projects and rarely revisit them: “I feel anxious to just go back and be like ‘Is it done yet? Is it done yet?’ So I’ll just kind of make something in one sitting.”

One of their important influences is Araki Nobuyoshi, a contemporary Japanese photographer, known for his juxtaposition of eroticism and bondage within a fine art context. “It’s just naked pictures, a lot of naked pictures,” they chuckle as they show me a book of his works. They were drawn to the quotidian nature of nudity depicted, in contrast with the religious and mythic nudity usually occupying museum spaces. Araki’s work made them ask questions such as “Why do we consider certain stuff porn and other stuff beautiful and art?” They are looking to embody the same stylistic features, while sparing the exploitative and voyeuristic aspects of Nobuyoshi’s work which come with the gendered dynamic of a man making images of nude women. They are also drawn to the work of John Yuyi, especially her depiction of the relationship between the self and technology, as well as her satirization of the idea of an online personal brand. Nan Goldin is another one of their favorites, especially the authentic feel with which she approaches themes of sex and gender. “I like how she shows people who are real people, who are struggling and who are not perfect, who are not the Dalai Lama or whatever. They are just her friends.” Other influences include A. L. Steiner, an eco-feminist lesbian artist, as well as Dido Moriama, whose repertoire has a quotidian, documentary aesthetic present in much of Em’s work as well.

Lolo

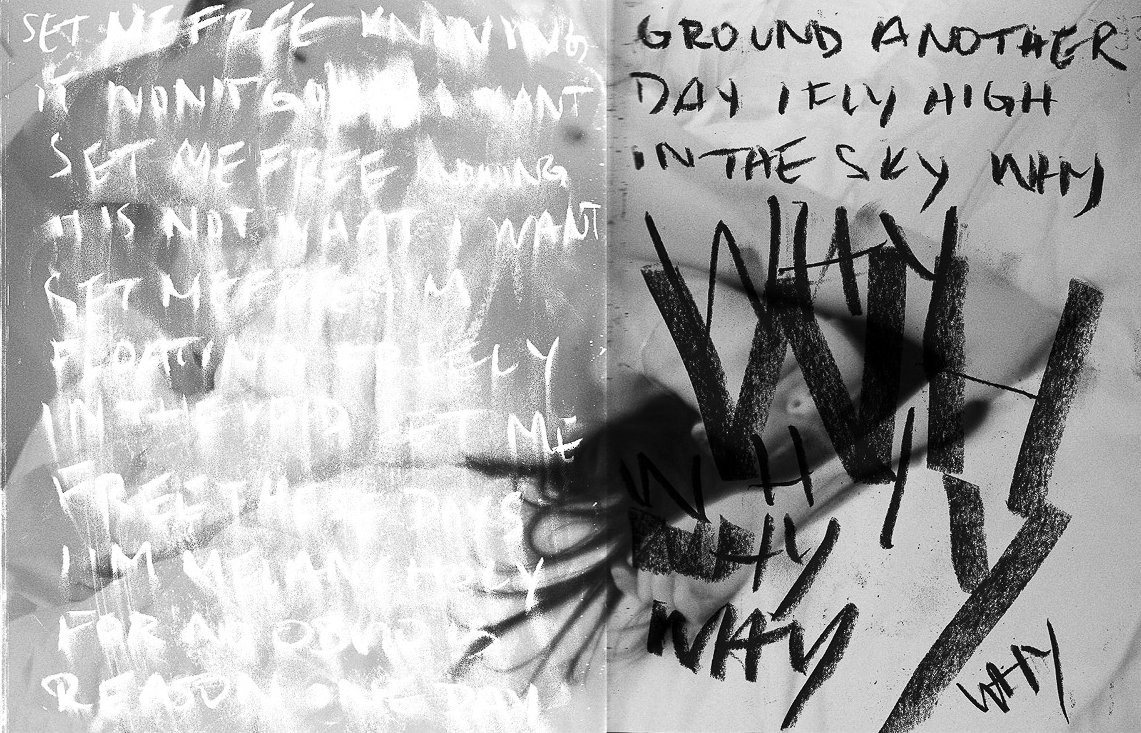

They see their work as deeply personal. “Feelings are very important, because they take up a lot of my headspace,” they tell me as I leaf through a book they constructed during the pandemic. The book is a portmanteau of charcoal writing, self portraits, candid images of environments, and fingerprints. There is a deeply intimate, almost confidential, feel in the book. It’s oddly physical, for a work that is entirely limited to the two dimensionality of its surface.

For Em, art requires a careful balance between interpretation and self-expression. They tell me about reading a quote from a studio conversation, claiming “If you need to be understood, you should go see a therapist.” Ultimately, they feel like “Art needs to say something, it says whatever is important to the person and that can be closer to home or further away. Mental health is a thing that happens to be close to home and Instagram is a thing that happens to be relatable to a lot of people.”

Their own relationship to social media has been a complicated one. In high school, they had aspirations of becoming a social media influencer as a way of connecting with others through shared interests. Growing up in a conservative college town, they felt lonely and isolated, seeing social media as a way of celebrating self-expression. As this was how they first gained interest in photography, they consider this experience an ultimately beneficial one. It allowed them to connect with people, share their work and get inspired. Yet it was also a source of anxiety. “I took a year off from school to care for my mental health, and people from home, even people from here too, would look at my Instagram and they’d be like ‘Oh my God, you must be having so much fun, you must be so happy, you look so amazing!’ And I was like literally I am miserable right now, I hate my life. It just kind of hit me that this shit is so fake.”

Despite its potential for authenticity and agency, social media also ended up being a place of fracture and misconstruction. Torn between being honest about their experience and leaning into the facade, they ultimately decided to tell the truth: “It made me mad that people would tell me not to say it, that it was embarrassing or shameful or that people would judge me or something. And I was like I’m working on my mental health and if people don’t like that I don’t really care about them, so. I will tell the truth.” Now, they see social media mostly as a business venture, maintaining it for networking and promotional purposes. They are grappling with the performativity of an artist’s online presence—the need to put forth an image of oneself as an artist while also remaining authentic to one’s own practice. “I am definitely aware of using social media to create some sort of cool artist image or whatever. I had a professor tell me I should keep up my social media presence, that’s how editors and galleries will find me. But I don’t like it, it still gives me a lot of stress and anxiety.”

Despite this increasing sense of commodification, their work expresses a belief in youth and the individual creator’s ability to construct a counter-narrative. They see the role of the artist as one of reclamation, as well as open communication. “I would like my art to be the thing that starts conversations. I feel like that’s so cliche, but if I could have anything, that’s what I would want. When I get messages saying ‘Your art made me have a conversation about mental health’ or ‘It really hit home’, that stuff is why I keep doing this,” they said. “Don’t we all hope that what we’re doing has a meaningful impact on people?”

While they may sometimes feel hopeless about the future and the increasing disconnection it holds, they also hold onto the hope that their art has meaning and resonance, making people reconsider their own engagement with social media and digital spaces, giving them a route towards imagining new possibilities of connection.

Currently they are drinking iced matcha lattes with almond milk, wearing partially transparent colorful outfits, and learning to screen print on mirrors. You can find more of Em’s work at: https://emsieler.com