Feature by Yao Lin

Photos by Maeve Cunningham

Gokul is a junior in CC majoring in Philosophy. They are a visual artist and a poet. They describe their art as a process of “harnessing and interjecting the forces of chaos onto the page.” Gokul’s art is heavily influenced by Islamic art, abstract art, and electronic and jazz music.

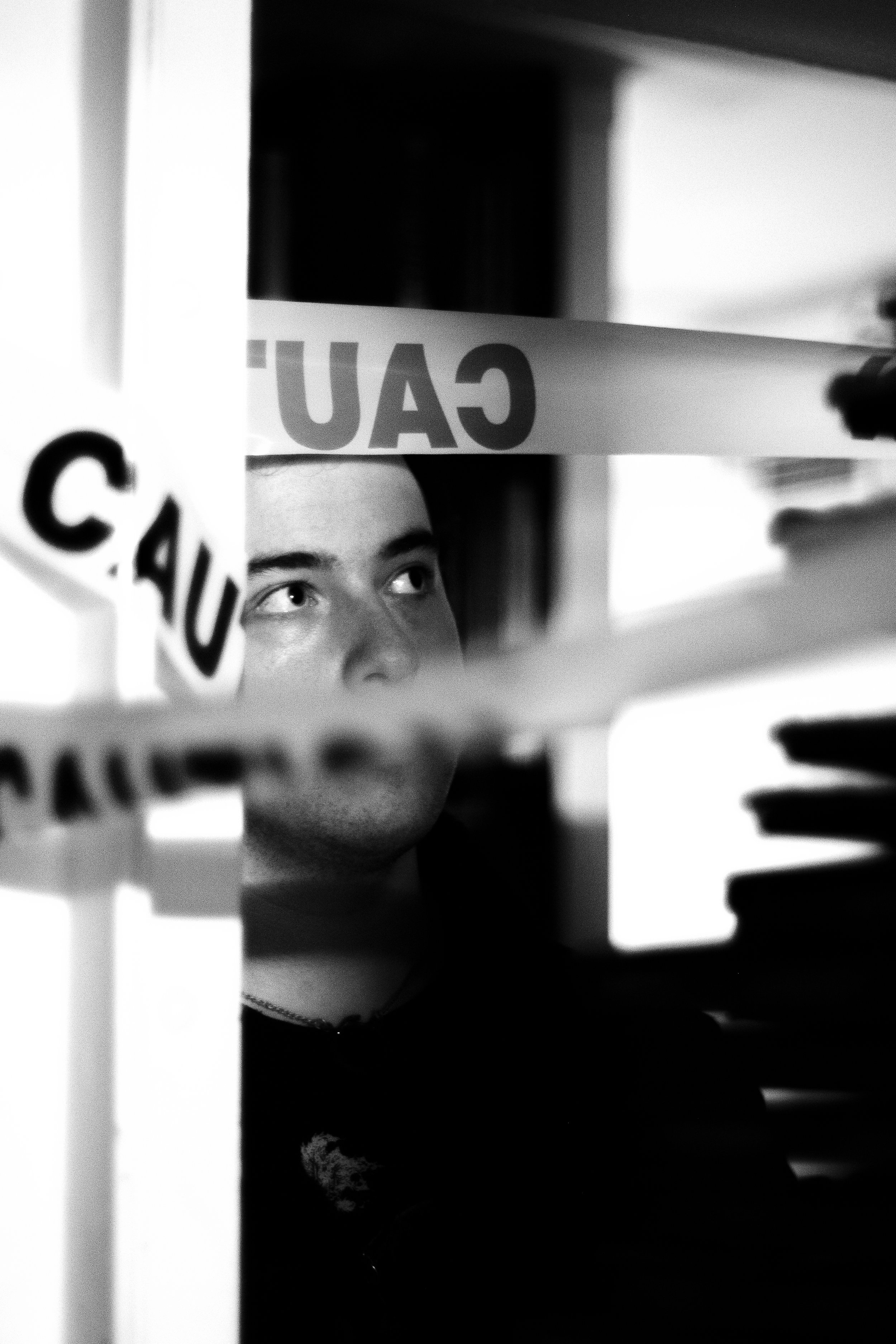

Entering 3R of Potluck House, visitors of the Special Interest Community cannot help but be wonderstruck by a wall full of collages, drawings and nicknacks hanging on the wall. There are photos of friends and family members, posters politely taken from elsewhere for demonstrative sarcastic purposes (an “avoid binge drinking” sign, for instance), and many pieces of drawings on black and white sketchbook papers. These drawings, varied in size and color, are the creation of Gokul Venkatachalam, a Potluck member, a junior in CC majoring in Philosophy, and a good friend of mine.

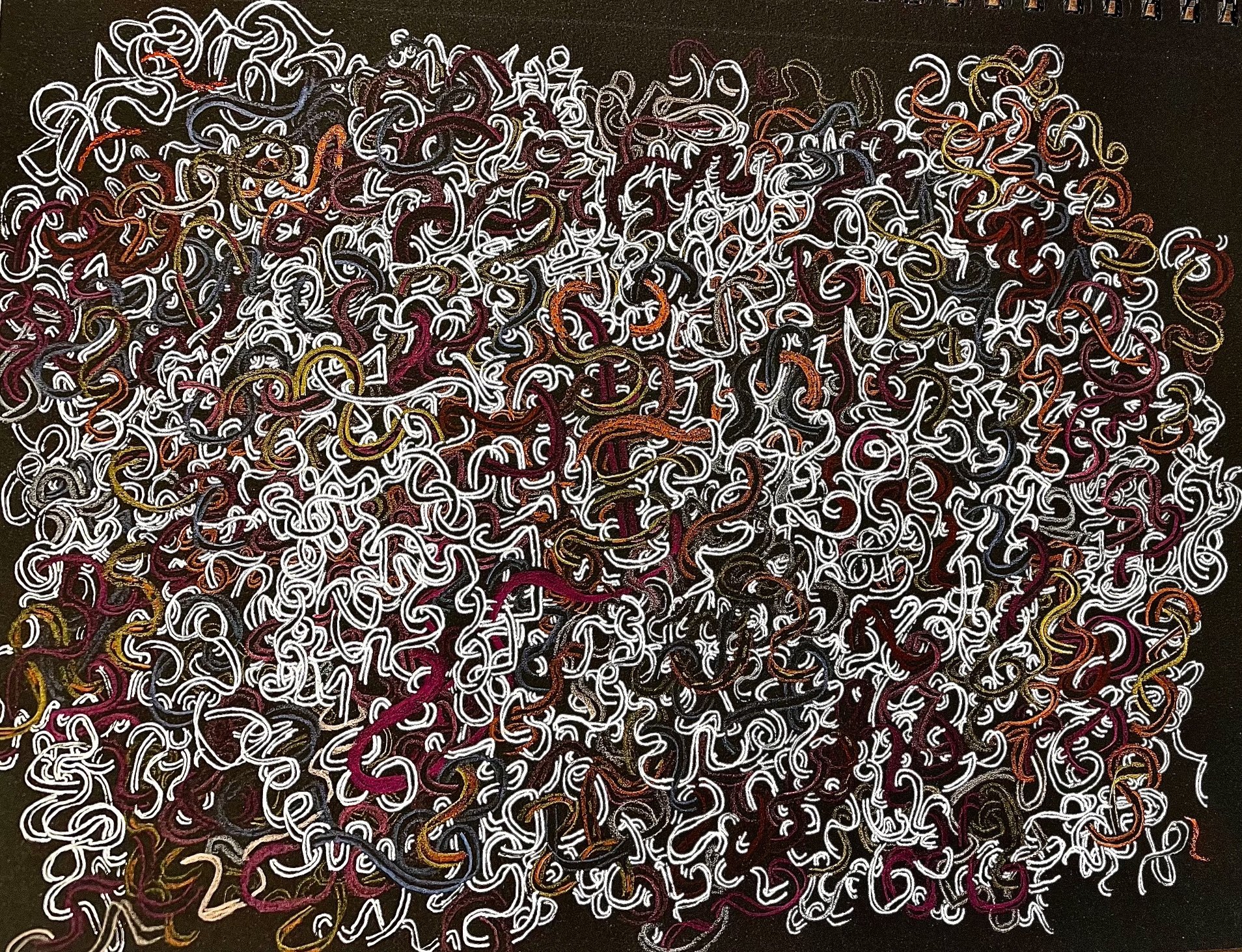

The decorations on the wall have slowly grown in size since the fall semester. Divided by a dinner table, the left side of the wall gradually became an enormous work of collage that documents the laid-back creative endeavors and daily lives of Potluck. Over spring break, Gokul and I decorated the second half of the wall, consisting of mostly their artworks. What I love the most among these pieces of work is a duo of drawings that I happened to put side by side. There is an accidental asymmetry: while one work is vertical, the other is horizontal. Such asymmetry is connected by their shared theme. Both of them resemble mountains, yet underneath the drawings’ loose representation of mountains, which at first sight seems to be a deluge of geometric shapes, is the core of Gokul’s work: it’s both non-representational and representational, both orderly and chaotic. Gokul’s work is a visual paradox that makes its audience’s gaze and thoughts linger.

To Gokul, their work to some extent is a vessel through which the stochastic and random makeup of our universe is manifested. Chaos and order are coterminous, and their way of drawing is a method to such paradoxical madness that we see in reality. When one looks at Gokul’s art, one sees unexpectedly realistic representations out of the clusters and compositions of geometric shapes. “It's really interesting that something can resemble something so continuous and compact—very real just out of an assemblage of scribbles or triangles, or tubes and knots,” Gokul says. The random aspects of Gokul’s art are in fact coupled with a lot of intentional choices of form. In their practice, they limit themselves when producing the geometric forms, while always trying to employ negative space and be precise in the types of marks they make. Sometimes, they pursue erratic, even mistaken forms of drawing. For Gokul, these artistic choices represent a very cognitive aspect of art: “This cognitive aspect of art, I think, is often underlooked when people think about art. Being more of a process artist, and being more of a conceptual type of artist forces me to think about my artistic choices in certain types of ways. And I think my philosophical background lends itself to that.”

Although most of Gokul’s earlier works consist of black ink on white paper, Gokul has been experimenting with color recently. While they focus on exploring the textures of things that one might find strange or unsettling in their black and white drawings, vibrant colors enable them to express a wider range of feelings, from joy to morbid horror. Last semester, after seeing an etching with white ink on black canvas at the Met’s Surrealist Exhibition, Gokul started experimenting with white ink as well as metallic pens on black papers. They found themselves creating different effects with this different set of materials. For instance, the white-inked pen is less finer than the black-inked pens, therefore the lines created with it are thicker and fuller, making it possible for Gokul to work faster, try new styles quicker and experiment with their art daily.

Islamic art has been one of the most important inspirations for Gokul. As a freshman, Gokul visited the Met and was dumbfounded to find themselves immersed in a world of Islamic art. Staring up at the Islamic geometry, in various tapestries, textiles, architecture, and even on the ceiling of the exhibition, Gokul discovered in themselves a passion for nonrepresentational geometric art. Gokul also found inspiration in the Abstract Expressionist movement. Jackson Pollock, MC Escher and Paul Klee among others have been big influences on their work.

Other than visual arts, Gokul also found their passion and inspiration in other art forms: music and poetry. Alice Coltrane was one of the jazz artists Gokul listened to when they first got into drawing—they distinctly remembered that they were drawing inscribed triangles. A part of Gokul’s process is to listen to the various layers of music, and try to translate the various movements in between those layers—whether it be layers of percussion, layers of stringed instruments, or how Alice Coltrane moves her fingers on the harp. Gokul would translate the movements of the jazz artist’s musical gestures and put certain clusters on the page, or make some geometric shapes bigger than others to emphasize a broader sound. Although one might not look at Gokul’s art and immediately hear music or see the resemblance that it has with music, their drawings are an art of the act of translation of one type of aesthetic material into another type. In fact, a few of Gokul’s close friends are jazz musicians. Listening to them while they practice, Gokul would usually feel the tone and the mood, and try to express the tone and the mood through geometric translation in their drawings.

Poetry is another significant aspect of Gokul’s artistic endeavors. Along with their jazz musician friends, Gokul hosted a jazz and poetry listening party last month and performed several of their poems there. Gokul describes poetry as a process of producing a voice inside of us that we didn't know that we were even capable of. To them, this possession of the poetic voice also comes through reading other people's poetry. “When you are really, really listening to the vocal timbres of speech, it's like really, really looking closely at the way things appear to the eye. It can get to the point where you will find every object very alien and foreign,” Gokul explains. I find their understanding of poetry incredibly relevant to understanding their art. Like how they focus on controlling the geometric shapes that construct the basic foundation of their drawings, Gokul has always been imagistic and focused on the acoustics of speech when it comes to poetry. “To write poetry is to produce the sounds in your head of how people talk, and you're surprised by how full and rich those voices are that you hear in your head. Honestly, even more than the speech that you hear outside when you're on the street.” Steven Jonas and Russell Atkins have been two of Gokul’s favorite poets for a long time. Although Gokul has found them doing opposite things with language, they converge on the same musical aspect of language that Gokul enjoys about poetry.

Recently, Gokul has been carrying out a collective art project. They ask others to complete drawings with them in various settings, whether it be at a party or just a laid-back hang-out. “Art is inherently collaborative,” Gokul says, “even if it's ultimately a drawing on a page. Despite the isolated concept of me or the self, any individual’s artworks are still contingent on the various relationships that they have with the people around them. Artists are always part of a wave or a scene. Being transparent and conscious of the fact that there's a bigger thing outside of you that's responsible for your ability to produce art is very important to me.” Last semester, Gokul had other people complete a self-portrait that they had started on their own. “I wanted to really reflect the people in my life that I see myself tethered and grounded to. Because I do feel like my sense of self is dislocated, sometimes disembodied, but more importantly, spread out amongst the people that I interact with. I can't really conceive of myself in any other way. So even when I'm alone, the voices and feelings of others are always with me. I think that's reflected in my art.”

What Gokul said at the end of our conversation in reflection about art—not only drawings, but music, poetry and all forms of art—is particularly moving. “Art is a reflection or a translation, leading me to split my sense of reality. Maybe a lot of my involvement in the practice of art is just trying to resolve the chasm that I feel between how my thoughts, the feelings are in my head and in my body, and how it is like in the external world. Resolving that internal and external chasm has always been something that I've wanted to do. And I think art––drawing, poetry, listening to music––has helped me feel more comfortable in my body, more comfortable speaking, and more comfortable expressing myself. Sometimes there are just a lot of things that I can’t express through language that visual art allows me to do so. As a person who experiences a lot of very rich and nonverbal forms of thought—non-representational forms of thought—It's my goal as an artist to show why that kind of thought matters.”

Gokul’s work can be found at @surfaces.depths