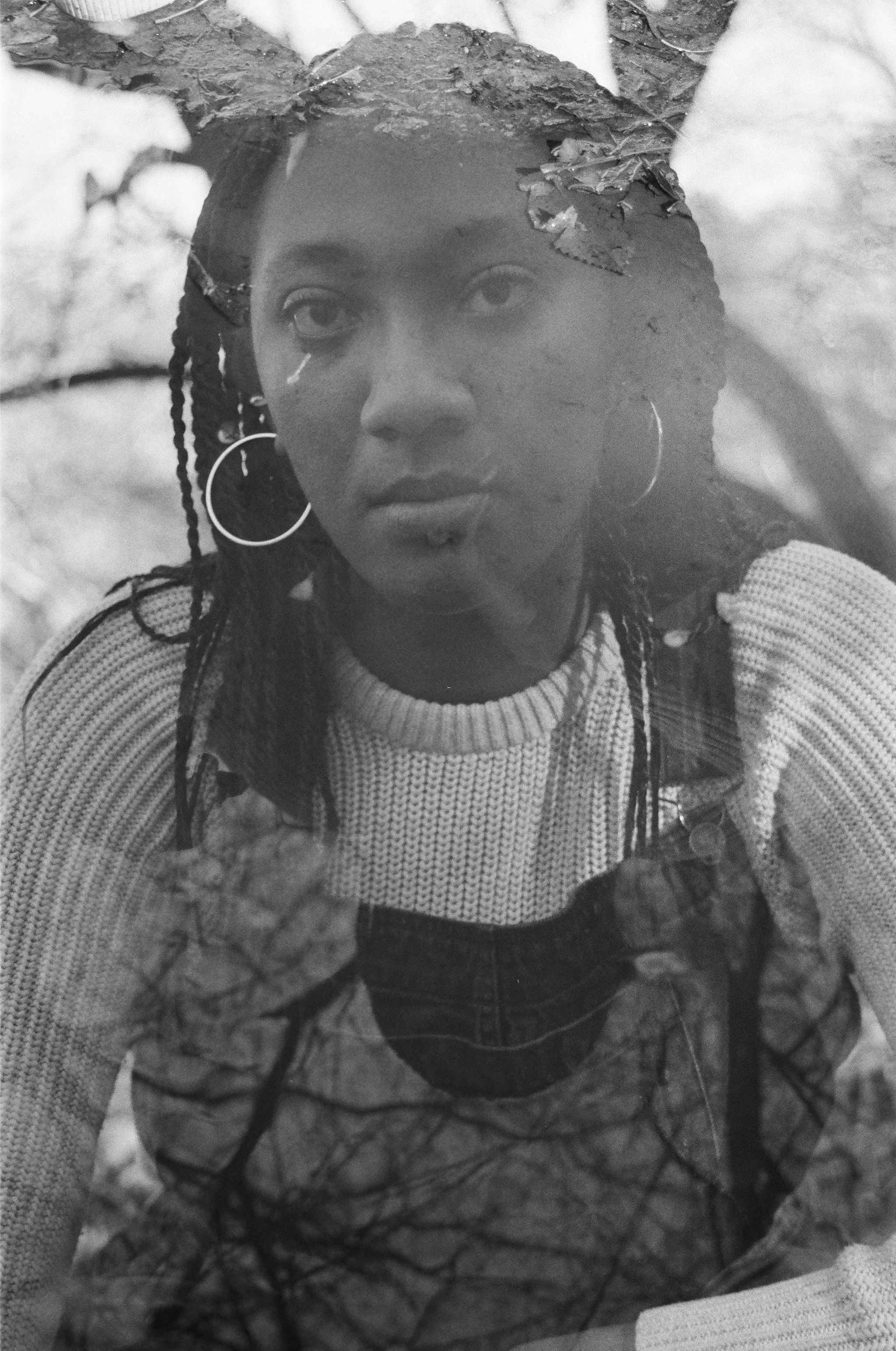

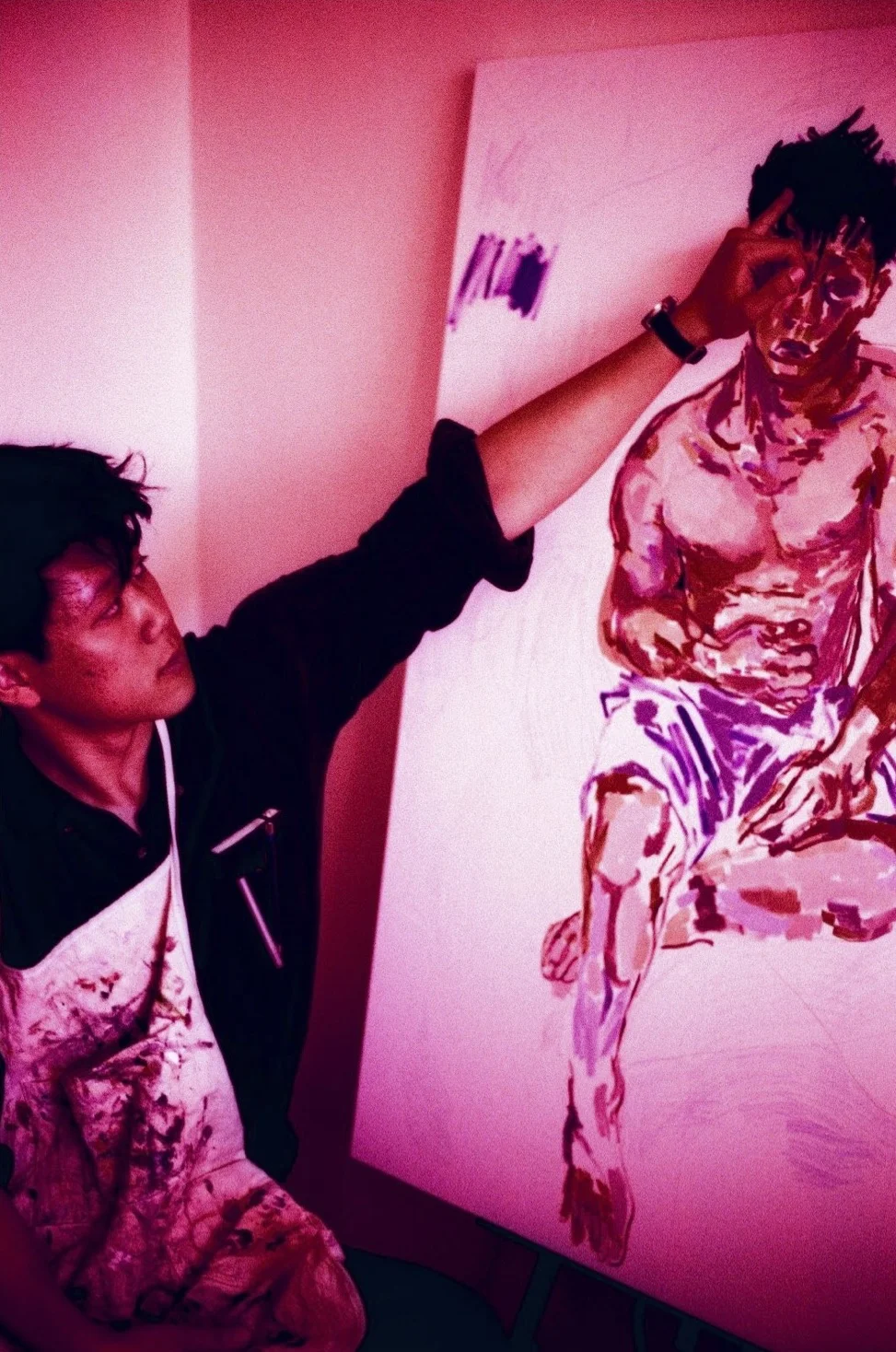

Photographed by Natalie Tischler

In conversation with Nigel Telman II

Mamadou Yattassaye has been a solo artist for a number of years but has recently set out to make a name for himself in New York along with our band soul for youth, a hip-hop/jazz band based out of Columbia. Through soul for youth I had the good fortune of meeting Mamadou and was recently able to sit down with him and talk about his evolution as an artist and his integration into the world of live music.

NT - Alright, sitting down here with Mamadou, this is Nigel with Ratrock. Go ahead and introduce yourself for us!

MY - What’s good, my name is Mamadou Yattassaye. I’m 19 years old. I’m a sophomore at Columbia College studying creative writing with a pre-nursing track (that’s TBD though). I’m from Harlem, NY - but my family is from Mali in West Africa.

NT - Alright cool, cool. So what three words would you use to describe yourself? I’m curious. Now that you’re introducing yourself to us.

MY - Well I think for sure number one — humble. I’m not the biggest person to brag about what I be doing; I just keep my stuff on the low. I’d say spontaneous. I feel like I can be quiet but in the right setting I have fun, get a little lit. And the last word: just grateful. I’ve seen a lot, you know, and I think through it all just being able to know that I'm still breathing and that I’m still alive for a reason, I still wake up the next day for a reason.

NT - You’re grateful for the life that you’ve gotten to live, here in New York, here in Harlem.

MY - Absolutely.

NT - But also at Deerfield, right? The boarding school you went to for high school -- how did you get out there from Harlem?

MY - Basically, I was part of a program called KIPP when I was in middle school. That program was helping a lot of inner-city youth be better academically and socially. Y’know we were surrounded by a lot of paranoia, a lot of gang violence and all that stuff in Harlem. Basically, the mission of the program is to bring a lot of inner-city youth together and give them, like, a structured, scheduled system to prepare them for high school. There were a couple counselors over there that saw the potential in me and they wanted me to get out of New York and see, experience some new things. So they helped me apply for boarding school. I only applied to Deerfield [Academy], though, because I didn’t really know where else to apply to. So I only applied to Deerfield and by Allah I was able to get into the school.

NT - So you’re from this predominantly black, predominantly African area in Harlem and suddenly you’re taken out of that and put in the cornfields in Massachusetts. How did that affect your worldview?

MY - Whenever I be reflecting on my journey, those four years were definitely a big culture shock. I was in the middle of nowhere, seeing cows, trees and all that stuff. And just being an inner city youth I was like, “What the hell am I getting into?” I was mad young, too. 13. I think all of that took me by surprise: Like do I even fit in, am I even ready for this environment? But if it wasn’t for that environment, I wouldn’t be as open-minded as I am today, with all of the different cultures, sexual orientations, people from all over the world …

I didn’t know how to interact with them, because I was marginalized by my environment. [In Harlem] I only knew certain types of people and I only knew how to approach things in certain types of ways. I always had to be two steps ahead because of my paranoia. So coming from that environment of Harlem to going to an environment where all the people are free-flowing and from all these different places, it made me realize what life is. The world is so big, so large, and so complex -- and it’s not only defined by the environment that you grew up in. But I was blessed enough -- that’s why I say I’m grateful, cuz I was blessed enough to have the opportunity to get out. Not a lot of people have the opportunity to get out of their environment. They don’t have the resources.

NT - And so ... just a quick background question, how long have you been writing poetry for?

MY- Seventh grade is when I started writing poetry. I had a teacher named Mr. Raysor who was in KIPP. He was my English teacher. Throughout that time he just had all these exercises bro where people could write creatively cuz he was a creative himself. So he was just pushing everybody. He pushed me, too. He was like, “Hey Mamadou, you should try writing; just write out some thoughts or whatever, and see what’s good.” So I just tried it, making it my own. Since then I’ve been writing poetry. Poetry is my first love. At first it was just, like, putting my thoughts on paper and then I started crafting it and they just became poems.

NT - So from 7th grade, when you first started writing poetry, did you ever notice a distinct change in your writing alongside your scenery change?

MY - I think what happened was the lens in which I was looking at the world was just sharpened and defined more, through being able to go to a school like Deerfield. Before I went to highschool I wasn’t really speaking. I had good ideas, but I just wasn’t able to articulate them the way I wanted to. So I was struggling with that - but I think that just going [to Deerfield] and being in that academic environment helped my learn to articulate my thoughts. [My writing] was still the same - there was some new imageries and experiences that I was writing about, but I was able to go back and write about old things. [My words] just got sharper. The strategies that I would use to convey my thoughts and experiences became more defined.

NT - So now, from the cornfields and cows of Massachusetts … Re-transplanting yourself into New York City but in a different space than you were before: Columbia University. I imagine a very similar student body to Deerfield in terms of the level of white people here.

MY - There’s mad boarding school kids here.

NT - Boarding school kids definitely come here. But basically, your old neighborhood Harlem - did you see any change in your writing from your move back to Harlem?

MY - I feel like my writing is always evolving, just every day. I feel like it be little things too that just, like, spark a change in the way I see things y’know? A conversation, a song lyric… So I don’t think my change to Columbia has been a big difference, y’know what I’m saying? In terms of my experiences, though, it is different, like, going to a school like Columbia but being from Harlem. My image of Harlem is totally different from what this is.

NT - Right, like this is definitely not the traditional Harlem area.

MY - No absolutely not. It’s a totally different bubble. The people here are just so… it’s like they’re within their [own] bubble. It’s weird when I go back home to be like “Bruh I just escaped, got out of a little alternate universe,” type shit, y’know? [But] I got my family, bruh. So above everybody else, above all the people, the core curriculum, I got my little sister, I got my mom, I have my dad, and I got my day one homies so it’s like ... no matter what bruh so I’m not really fazed by whatever this school be throwing at me.

NT - And so would you say your writing is sort of, like, a stream of consciousness from what you observe and what you perceive in the world and that kinda flows out when you’re writing or when you’re rapping?

MY - I mean yeah because I’m always inspired by, like, my environment. That’s what continues to make me write in different ways, write about different subject matter and the way in which I go about it, different perspectives. So I think that’s true. The environment and people I talk to influence the way I go about the specific pieces of writing I’m doing and in terms of style and language.

NT - Speaking of, what is your writing process? How do you sit down and decide what you’re going to pen on the page?

MY - I don’t know, my style is very spontaneous bro, because I can’t be forced to sit down and try to mash out a poem. I mean I probably could, but I wouldn’t be proud of it, y’know? It just happens where I experience something, or I hear something - either through a song or a lyric - or I’ll talk to somebody, or I’ll see something while I’m walking; and right there in that moment I’m sparked; and in the next 20 or 30 minutes, I’m just writing down everything, and it’s kinda like word vomit, just writing anything. And then once I got all my ideas and creative things out, now I try to format it and revise, revise, revise; make sure the way in which I wanna say things is precise. That’s how I be writing my poems. And it's similar with how I write my lyrics too, with rap. I have the same spark, have a certain subject matter in mind, just word vomit and then try to match that with the way I wanna say things, cut off words, revise. So I mean they go hand in hand in terms of my approach in lyrics for rapping and my poetry.

NT - When did you first get into rapping, actually? Because I know it wasn’t when you stepped foot on this campus.

MY - High school. I was just doin’ it for fun. I had my bro, Tarek [Deida, CC ‘19], he go to Columbia now too. Cuz I met him over there and I started rapping with him - he be rapping - so I just started rapping with him and trying it. It was whatever, it was just for fun bruh, and I wasn’t really good.

NT - Do you see the connection between hip hop and poetry? I know a lot of people do but there are also plenty of people who would say they’re two different things.

MY - I do. I mean I’m starting to get annoyed a little bit, bruh, people categorizing me as only a rapper. Cuz, like, I just started trying to rap, y’know? I was always a poet first. So I mean it’s cool, like it's whatever. Rap is an art form too, of course, but there’s a certain stigma with what rap is today. It kinda marginalizes people. It’s like “Oh if you’re a rapper you sound like this,” or whatever. I don’t know, I always like to tell people first that although I do rap I’m still trying to figure out how to be better because I’m a poet bro, you feel me?

NT - Where do you see yourself in terms of other rappers, other artists? How would you put your work in comparison to people like Kendrick Lamar, Drake, y’know, Lil Pump, Kanye West?

MY - I think in terms of style the person I’m very inspired by is Noname. Cuz she’s a poet first too, and you can literally see it in her songs or whatever. So I think right now, like a Noname. A little bit of Saba - that whole Chicago collective I think I really resonate with.

NT - I feel a lot of Chicago from you.

MY - I’ve been telling people, I’m a Harlem kid but I’ve never been the stereotypical type of New York dude, you know? I’ve always been the quiet, reserved, observant type of kid so I didn’t really catch on to all the gritty. I mean I can get gritty with my verses if I really wanted to but the trend which I do is very reflective, very calm, laid back. I feel like whatever I write has to be a representation of who I am. I’m a laid back, observant, like to have fun type of dude.

NT - Authenticity is very important to you, yeah?

MY - Absolute- that’s first. That’s major, to be authentic. Cuz that’s all you got bruh, to be yourself.

NT - What would you say your top five hip hop albums are?

[after much deliberation]

MY - I gotta put “All Eyez on Me” by Tupac first … I gotta put “To Pimp a Butterfly” up there … probably, like, “Beats, Rhymes and Life” by A Tribe Called Quest. I just love that album. That’s three so far. Yeah this is definitely not top 5; these are just albums that I listen to. “Telefone” by Noname bruh. Yeah that’s an album I bump.

NT - That is a potent album. The replayability of that album is ridiculous. You can listen to it 10 different times and hear something different each time.

MY - She’s probably one of my biggest inspirations right now in terms of, like, the way in which she attacks her music. Saba too.

NY - You’re like a student of them too -- you study them, right?

MY - I study that shit bro, I be studying Noname lyrics. I be reading on Genius, y’know, seeing how she’s doing her flow, her subject matter, crazy … I’m tryna think … I mean “Care For Me” too … Alright so all in all bro those are the five albums I’m listening to right now but that is not [my top 5 of all time] - that’s my disclaimer. “All Eyez On Me,” “Beats, Rhymes and Life,” “To Pimp a Butterfly,” “Telefone,” “Care For Me.” That’s all the albums I’m listening to right now, that don’t mean they top five of all time. I listen to too much music bruh.

NT - Alright, so let’s pivot a little bit and talk about performance. Is it accurate to say you’re more of a spoken word artist rather than purely written?

MY - Yeah! I’m trying to be more spoken word because before I had a big problem with trying to share my work. Just being able to be comfortable. But I think now I’m starting to evolve into more of a spoken word artist.

NT - Oh so when you were writing you weren’t thinking about how you were gonna say it.

MY - Right because it’s a big thing to be able to write and perform because, like, some people are just great writers and aren’t able to perform. For me I thought that was me. And that’s something I’m still working on. I’m still tryna be better and evolve.

NT - So as, like, a spoken word artist, how do you approach performance? How would you prepare for a show somewhere?

MY - I don’t even know. I remember Robert [Lotreck, drummer and fellow soul for youth member] asked me that the other day: He be like “oh how do you prepare to perform?” I was just like I don’t know bro. I just kinda mentally run through it, and then just like [perform]. I like to gesture too and look at people.

NT - Do you see some growth as an artist and as a writer based on your time in the band [soul for youth]?

MY - Yeah I think being more confident in my lyrics and how I express myself through them, and really holding a connection with my lyrics even more. I always held a connection, obviously through writing; but when I perform it too, I’m saying those words, I’m reciting those words, and it feels even closer. So I think I’ve evolved in that, and just being able to perform for big crowds and stuff because I was not used to that.

NT - Right and it seems like you’re getting into the flow of it a little more. At the Rockwood Music Hall [http://rockwoodmusichall.com] concert you were doing a very good job of audience interaction and just being with the band in general. I feel like last year all the way to now you have grown, in performance, to become more a part of the band as opposed to just a frontman. Now you have Robert stopping on certain things for emphasis. You queue us: you queued me to start the bassline a few times. I feel like now the connection between you and the band is like, less separated. It’s coming together.

NT - So, not counting soul for youth performances, where have you performed?

MY - I’ve performed at a little event at my school called Koch Friday Night and I performed at this writers conference, my poem. That conference was the first time I read my whole poem out. The writers conference was in Vermont at Middlebury College, so I was over there.

NT - How’d you get involved with that writers conference?

MY - Oh my english teacher helped me apply. There were a lot of writers from the New England area and we was just looking. That was a different experience too, bruh. It was like three days but that shit was crazy.

NT - How was that by the way? Do you think that affected your writing as well?

MY - A little bit because it made me more confident.

NT - So confidence is a big key to how you write?

MY - Yeah. That conference was a little thing that motivated me. Because I was sharing with people outside of my high school at the time and I was still in the process of being comfortable with that. I remember after I read my poem they were taking pictures of the page. They were passing it out for selected regions to read. And there are still some people I talk to from that program that be asking me about my writing.

NT - So now that you’re in college, I’m curious, you talk about being a poet, talk about being a rapper… how would you squarely define yourself?

MY - I would say poet but also just an artist. I don’t know I’m just always trying to continue to evolve as an artist.

NT - You’re a product of your environment and your environment is so varied you can’t be defined by one thing.

MY - Right, so I feel like I consider myself just an artist now.

NT - Speaking of your environment, you’ve made a few comments about your childhood environment informing a lot of the content of your writing. You talked a little bit earlier about the paranoia you felt growing up, do you think that was a product of the Harlem environment?

MY - Yeah I think, yeah… you know a lot of kids, bruh, they don’t have outlets to express things. There’s a lot of mental health problems in these environments, you know what I’m saying? There’s a lot of concerns of PTSD; somebody’s seen somebody that they loved, loved ones getting killed shit like that. So I think that PTSD and paranoia and all of that stuff -- and other things like schizophrenia and just health disorders bruh there’s not a lot of outlets for people like that in these environments and there’s not a lot of awareness in these environments too.

That’s why I say I’m grateful because I had a teacher and I had a program like KIPP to at least give me some of the resources to help me on my track in terms of finding myself and what I want to become outside of my pre-existing environment. So I think whenever I write, I try to stress in some way that paranoia, but also that growth too. I’m tryna evolve, I’m tryna be better. It’s not perfect because sometimes I can revert to that, that paranoia and those moments. But it’s all in the growth, y’know, it’s all in the evolution, who I wanna become as a person.

Writing has definitely been that way of allowing me to narrow it down to what I should be becoming. I mean it’s cliché, but I consider everything I do to be poetry in motion so the grotesque and the beautiful has a certain cohesion. The way I believe in things, bruh, God, Allah, wouldn’t put bad stuff or good stuff for no reason. There’s no reason why there’s a bad or there’s a good thing without a purpose. Everything has its intention. There’s a beauty with that y’know? So I don’t regret anything that has happened to me. I mean obviously there’s been times, but when I reflect and been more mature - I’m blessed to be able to experience the bad and the good. It’s shaped who I am as a person, you know? I wouldn’t be who I am without all of those experiences.

NT - What do you hope audience members get from seeing you rap, seeing you perform your poetry etc.? Is there something you wish to impart on them?

MY - I mean I just hope they hear my perspective and, if anything, it sparks a new perspective. That with the words and stuff that I’m saying - I mean obviously you can’t fully get into somebody’s world but you can have a preview or a sneak peek into my mind or the things I’ve gone through. And if I can at least have sparked a change in somebody’s mind then I’ll know that I’ve done something with my writing, you know? To make people think a little bit differently, that’ll have been an accomplishment for me. I think that’d be my intention: for people to really listen, hear the words and just think about things a little different and consider their own perspectives in comparison to my perspective and just in general. And just grow. I’m growing, I want people to grow with me too.