Feature by Sahai John

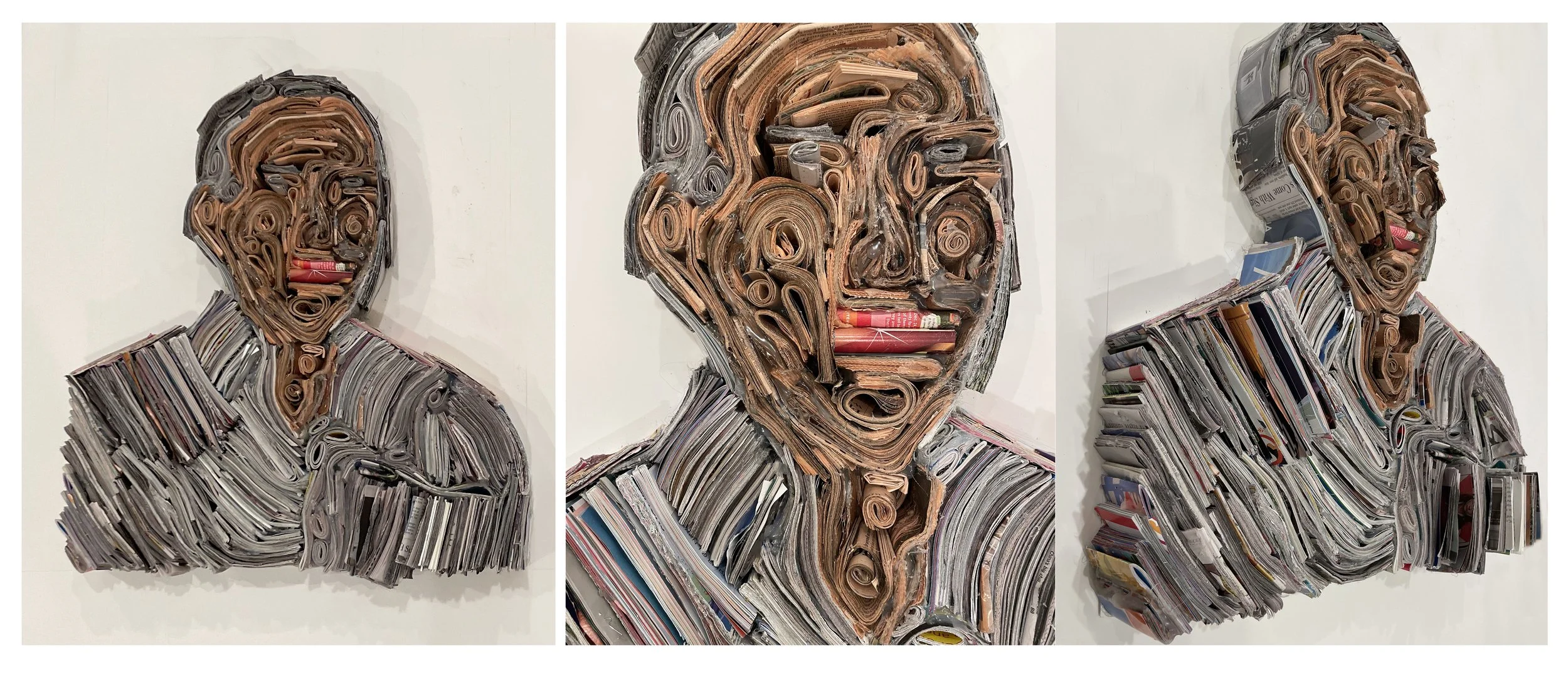

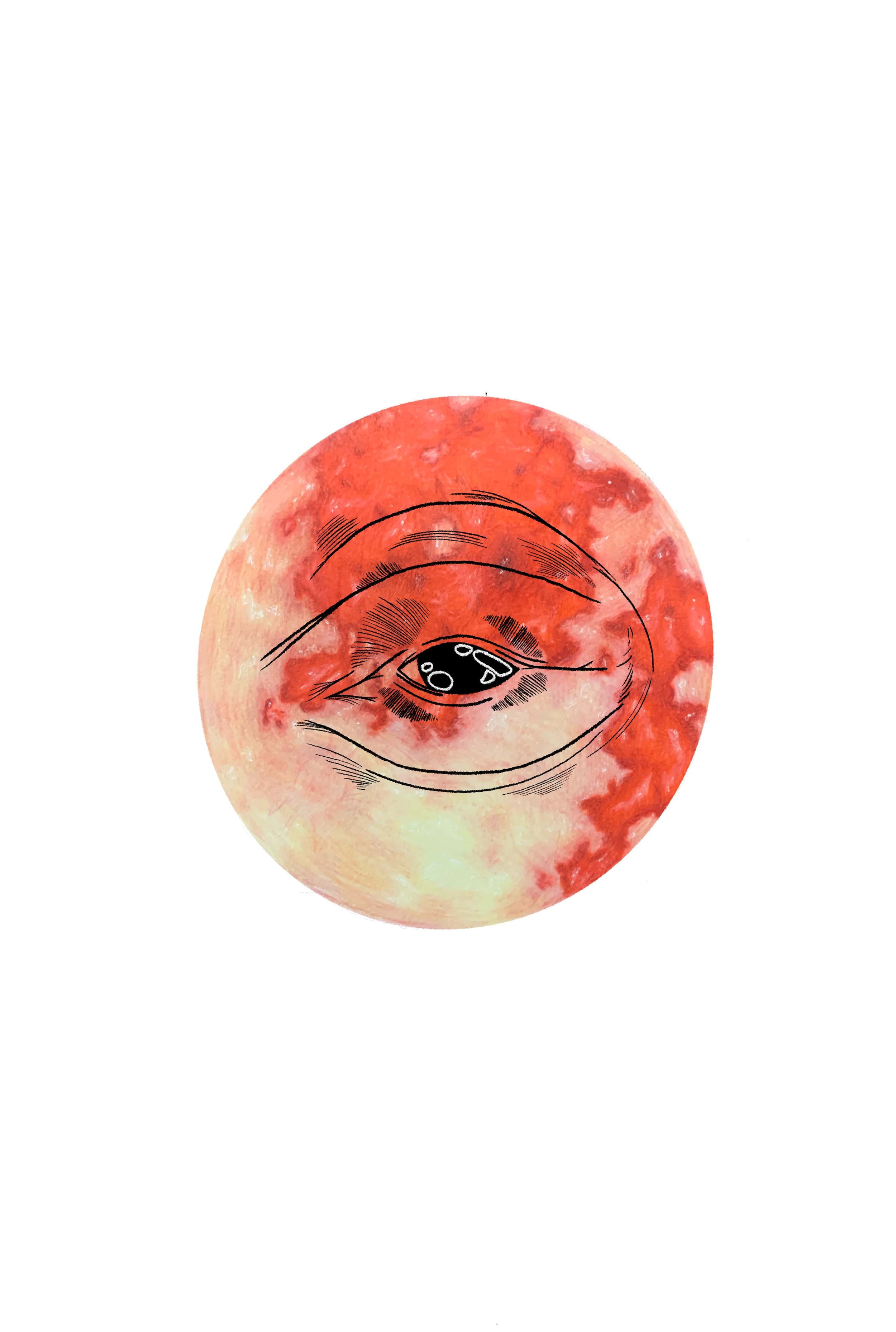

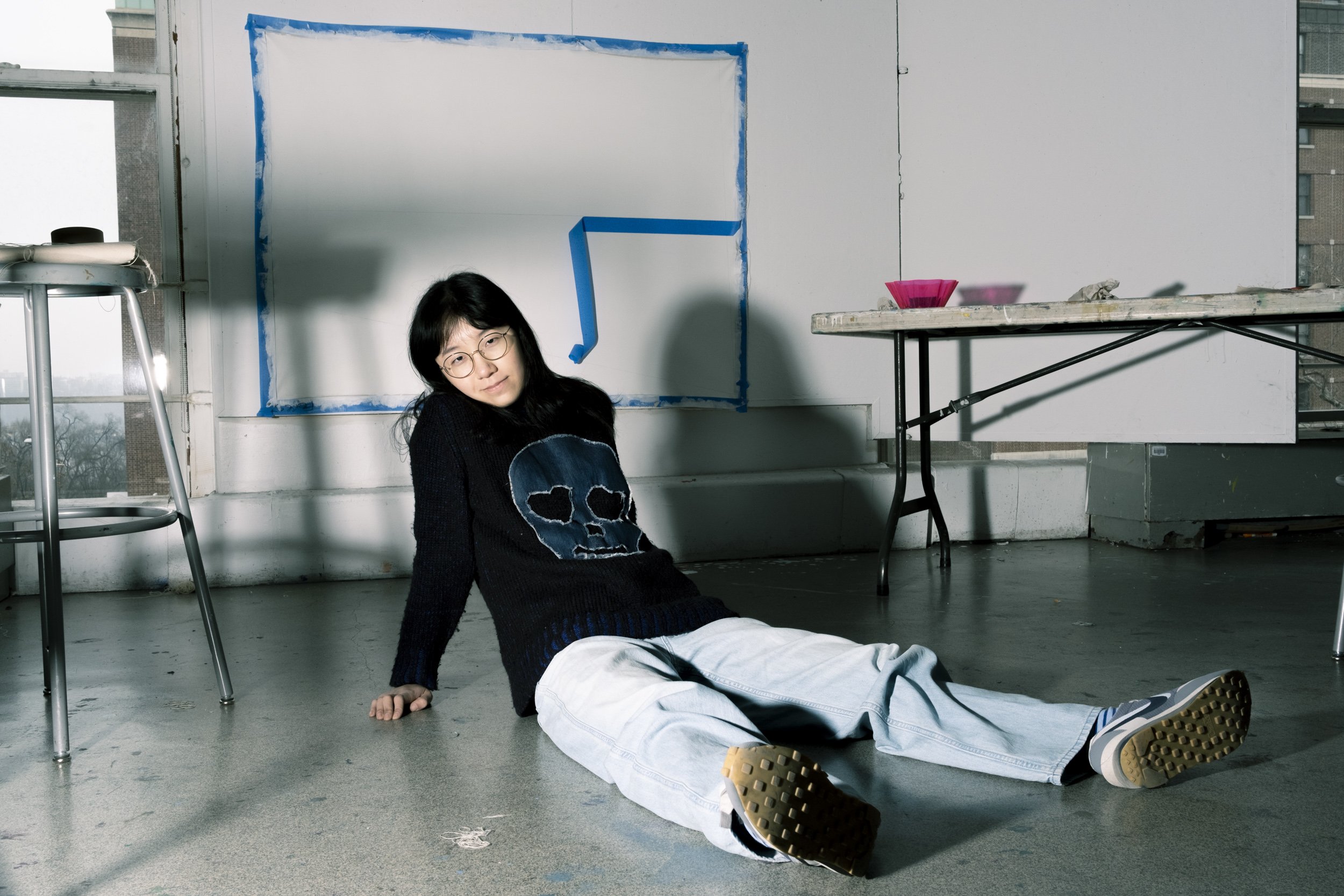

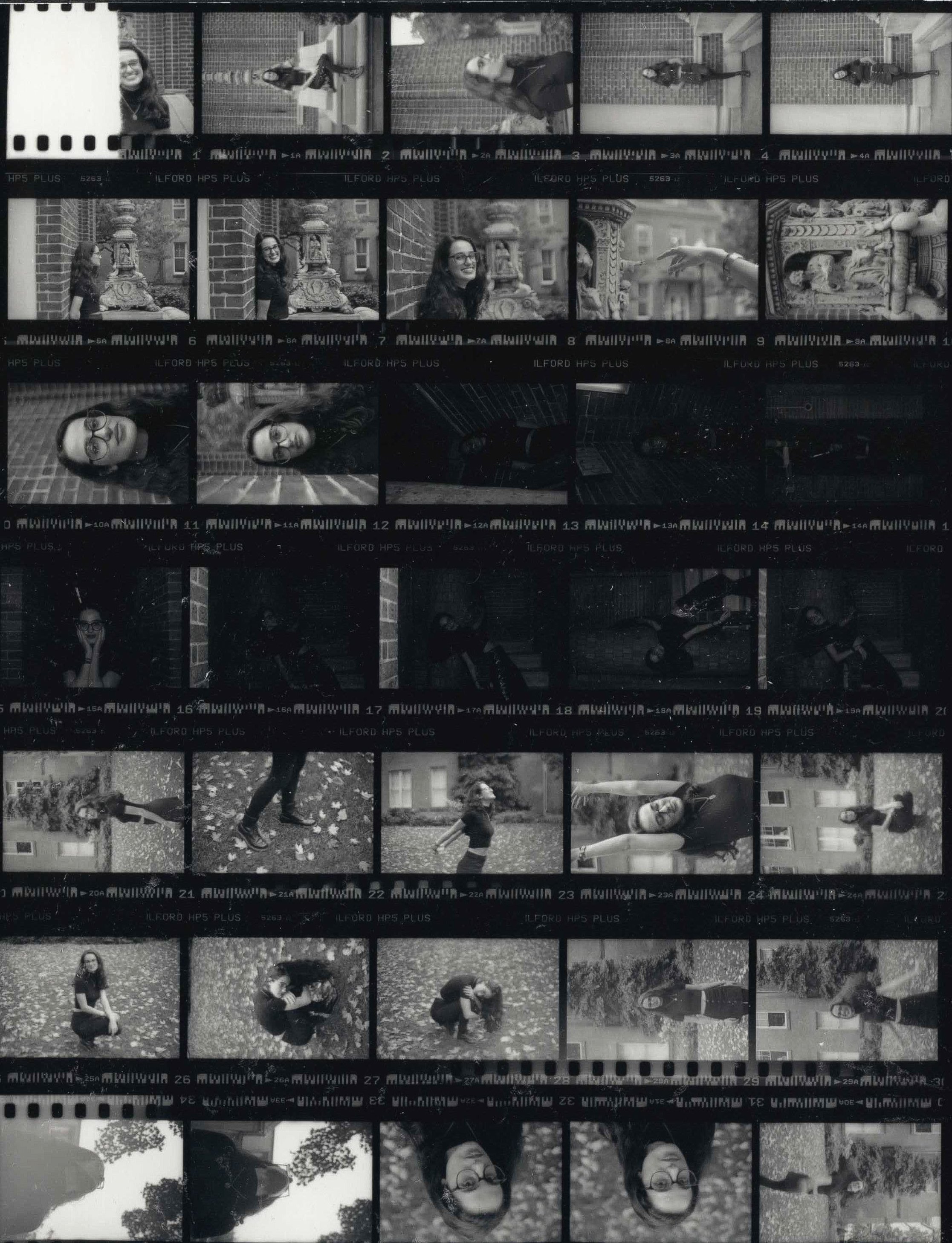

Photos by Norman Godinez, as part of their self portrait series: Normans, 2023

Norman Godinez is a senior in Columbia College majoring in English. He is a photographer and filmmaker from Miami. Norman’s work ranges from fashion photography and portraiture to short films and polaroids. He features modern photographs inspired by Baroque and surrealist artists such as Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Alphonse Mucha. Norman plays with narratives told by authors and artists he admires, telling new stories through his own work.

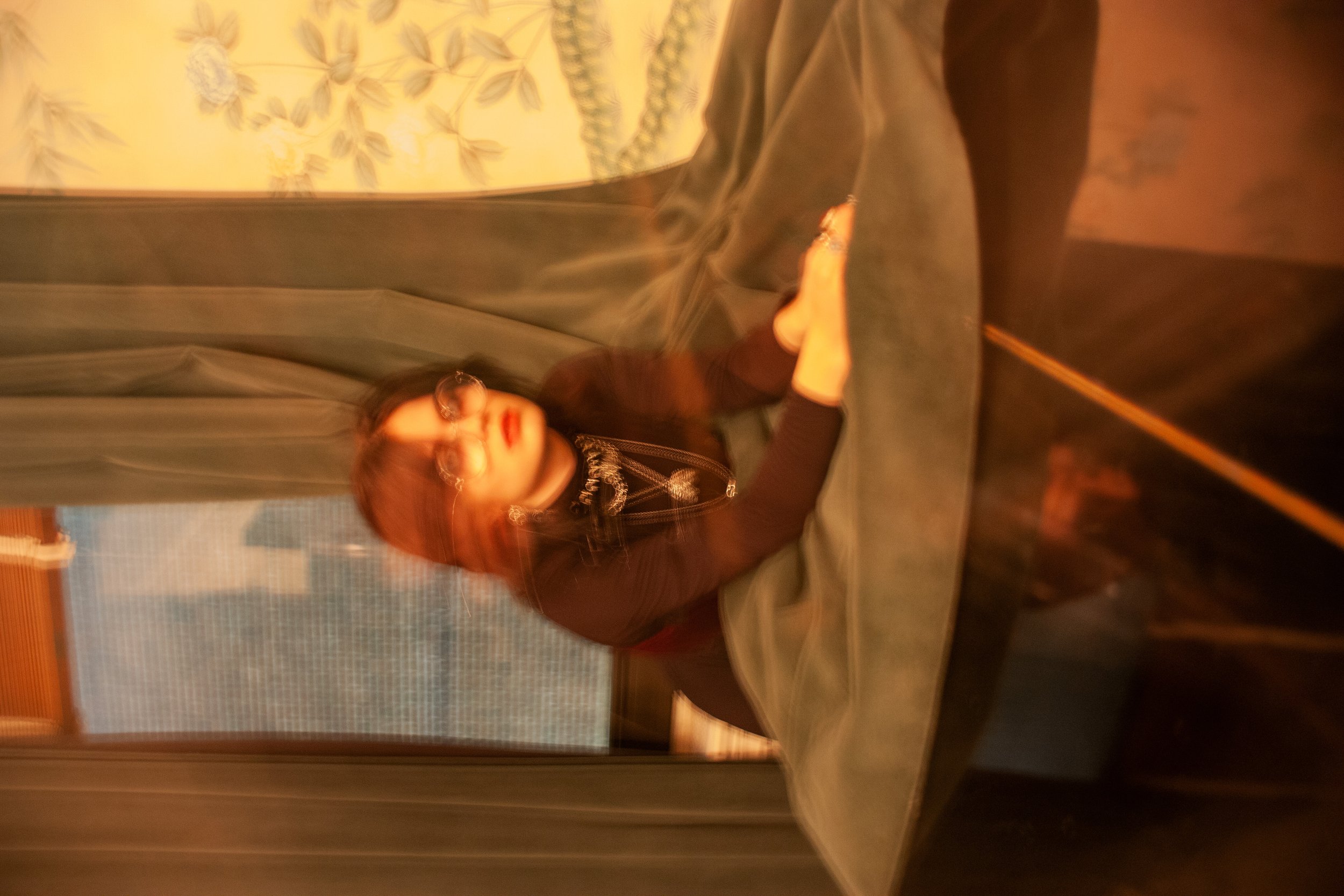

Norman and I met outside of Shake Shack before walking west to Riverside Park. We found a bench beneath the trees where, a year prior to our interview, early morning sunlight illuminated Norman’s elegantly dressed friend, Alexis, and the surrounding autumn foliage in a shot from his photo series, The Ecstasy of St. Theresa.

The Ecstasy of St. Theresa, 2022 (I)

Early in our interview, Norman told me that he likes to imagine entering different worlds with his work by encouraging the people he photographs to play a role in the Mucha, Bernini, and Mary Shelly inspired scenes that he builds in each shoot. And, as Norman sat beside me with a red silk scarf tied around his neck and tortoise shell spectacles tucked between the buttons of his black blazer, politely eating a red apple in the slightly overcast park, I couldn’t help but imagine that we, too, were in one of his constructed universes.

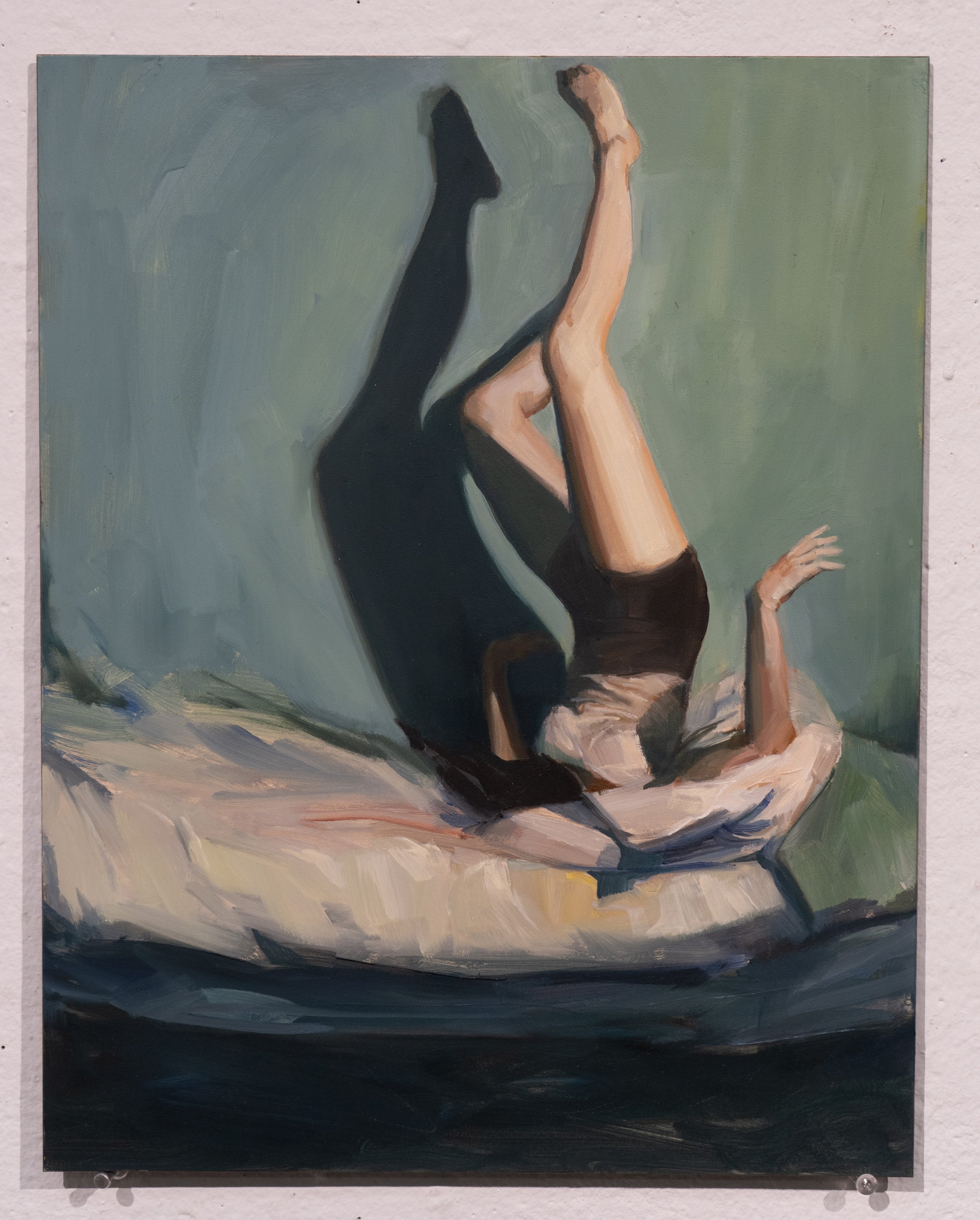

Norman enjoys collaborating with his subjects to create these dreamy portraits. “I like for my subjects to have a good narrative in their heads, even if it's not the point of this photograph, even if they're not playing the character that I'm giving them, I still want them to have a character to play.” Norman tells me that he either gives the people he photographs a story or inspiration to follow or he’ll give them explicit directions on where to look and position their bodies throughout the process, conducting his shoots like a film director putting on a production. Either way, he explains, “every time we go into a scene it's almost like an action. That language has always helped me to connect with people that I shoot. Everybody that I've taken pictures of, we come out of the project a lot closer together.”

Mucha-inspired Lilies, 2023

Norman took me through his creative process by describing the experience of shooting his friend Alexis for The Ecstasy of St. Theresa. “I knew that I wanted to shoot Alexis. That was it. And I remember that Alexis wears a lot of white monochromatic clothing and has a very distinct style. A lot of those pieces are Alexis's clothing and they were inspired by an Alexander McQueen fashion show where there was this kind of heavenly rain happening. That's how I decided to connect it to Bernini’s Ecstasy of St. Teresa. And then I shot it somewhere over here [in riverside] at like 7 AM.”

The Ecstasy of St. Theresa, 2022 (II)

Norman’s earliest memories of exploring photography are from when he was nine years old and took photos on his first camera of his dog who he wrapped in a pink fuzzy blanket like a one-shoulder dress. His skills have since evolved and he now plays with the language of fashion photography while maintaining his own sense of style and humor. Norman hopes to expand his creativity in photography by incorporating themes of nature into his photographs. He explains, “I like nature a lot. I love how powerful and overpowering it can be. I like that a lot of fashion photography has been of pretty people and pretty nature, but I would love to show, in the language of fashion photography, people in crazy environments that might be a little dangerous, like tundras and deserts, to show a little bit of how disconnected we are from the environment.”

(Untitled), 2023

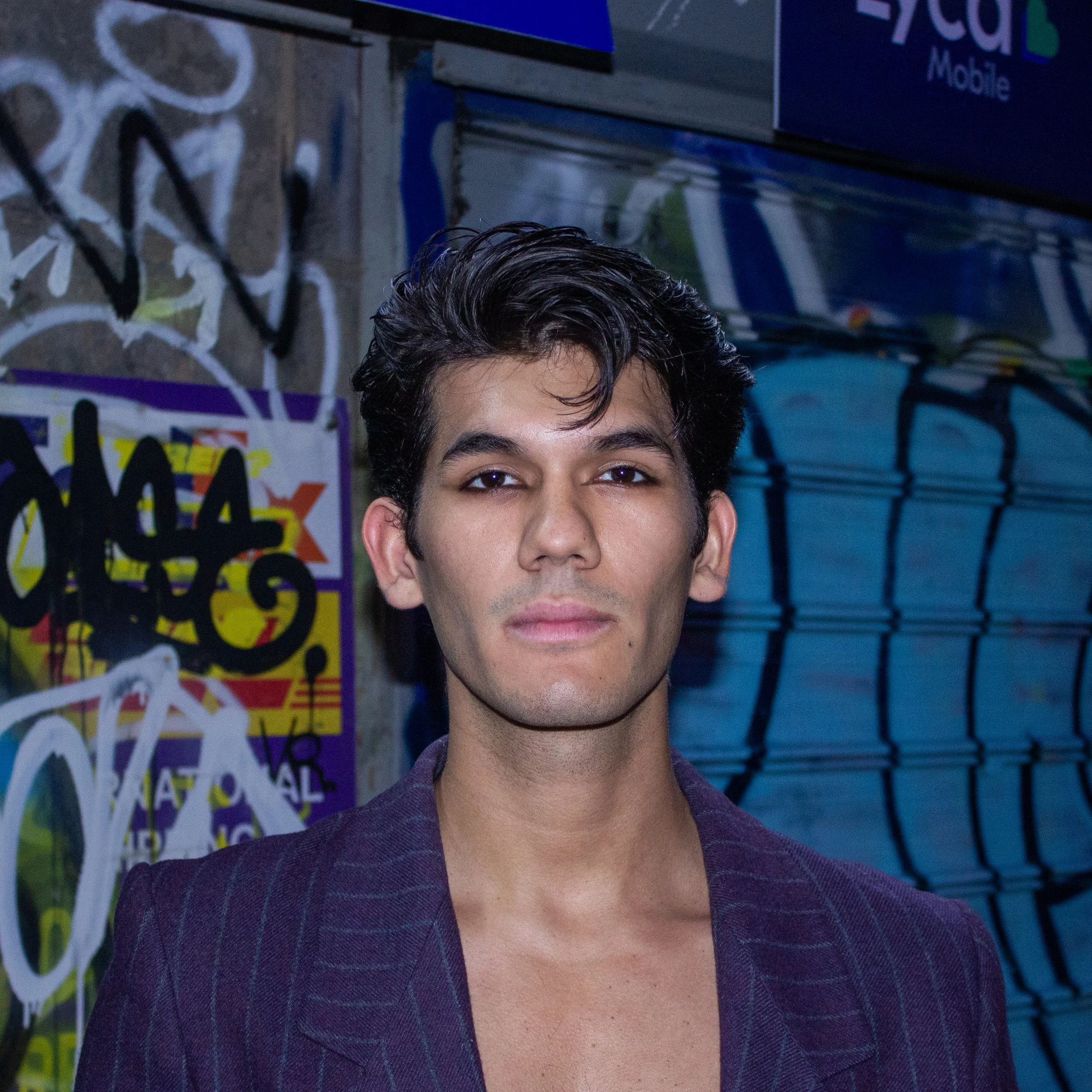

Norman described this process of incorporating fashion photography into his work while adding his own aesthetic and meaning as he talked about photographing a friend he met in Paris for his Paris Editorial series. He explained, “I wanted to play with the language of fashion photography. To me, that meant maneuvering through a day in Paris in a really annoying, ‘fashion way.’” Norman played with this language by photographing iconic locations in Paris. He took photos at the Tuileries Garden, the Pont Alexandre III bridge, and the Bouquinistes. “Two or three months ago, during summer, I saw this Richard Avedon show,” Norman told me. “A lot of his fashion photographs were at the exact spots that I photographed, and I had never seen them before. But it was like we both understood the weight of those iconic locations. And I know Richard Avedon might have wanted to use them in a way that was not ironic, but I kind of wanted to poke a little bit of fun.”

Paris Editorial, 2023

Paris Editorial, 2023

Although he takes his work and their subject matters very seriously, Norman includes subtle bits of humor throughout many of his series. This is one of the more playful aspects of Norman’s Alas commercial. “Just thinking, this can be funny, and giving myself the permission to look at the commercial as if it is funny, brings out a lot in it. It's so supernatural,” he says. Norman enjoys exploring the language of advertisement. He’s interested in the way that commercials use elaborate lighting, settings, and costumes to depict a moment that doesn’t exist but is being given to the audience as if it does and is just part of an ordinary day in someone’s life. Making sure that his own commercial was not as disconnected, however, was important to Norman. “The commercial connected art in a lot of different ways, especially really human emotions like laughter, humanity, humor, as opposed to a very elevated, almost detached way, which happens sometimes,” says Norman.

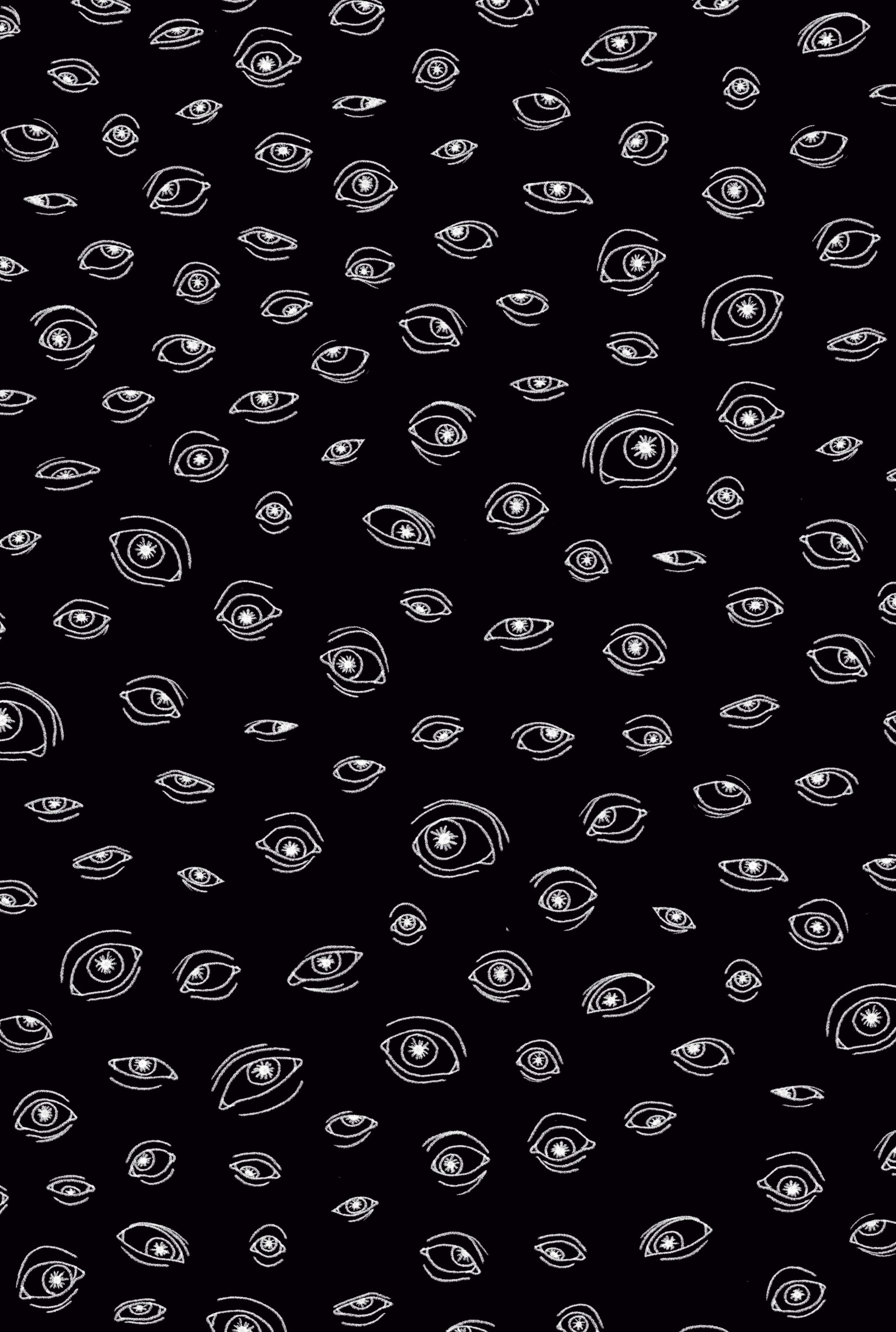

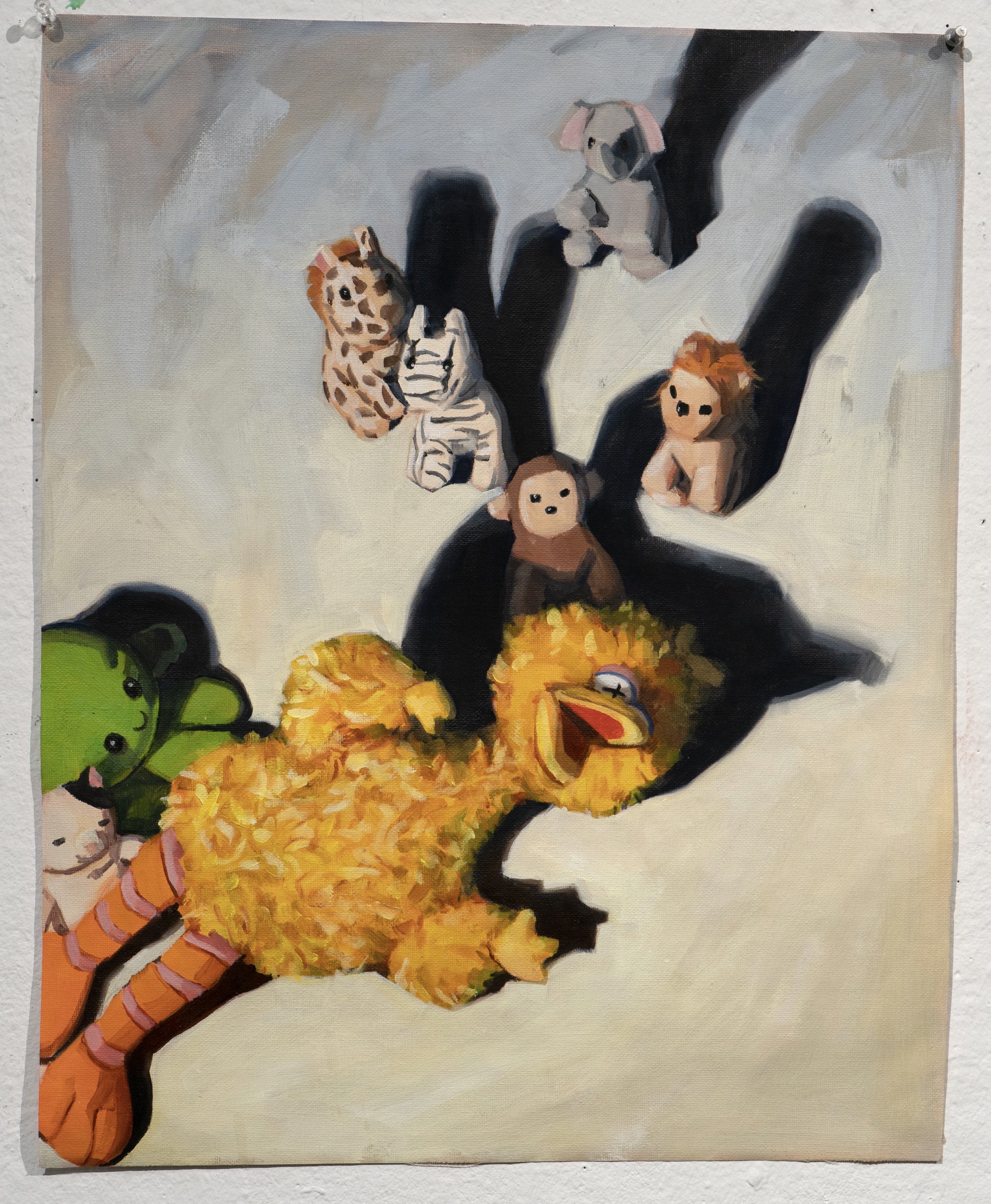

Throughout his work, Norman weaves multiple themes by playing with movement and nature in his photographs. “Maybe, in these contrasting black and white ones, It's eaten up a little bit, but it's still there. In one of those, my subject is hugging the shadow of a tree and then the Paris Editorial has this movement where he's eating an apple. So there are all these nature motifs that I really love, and I think that's what translates as dreamy.”

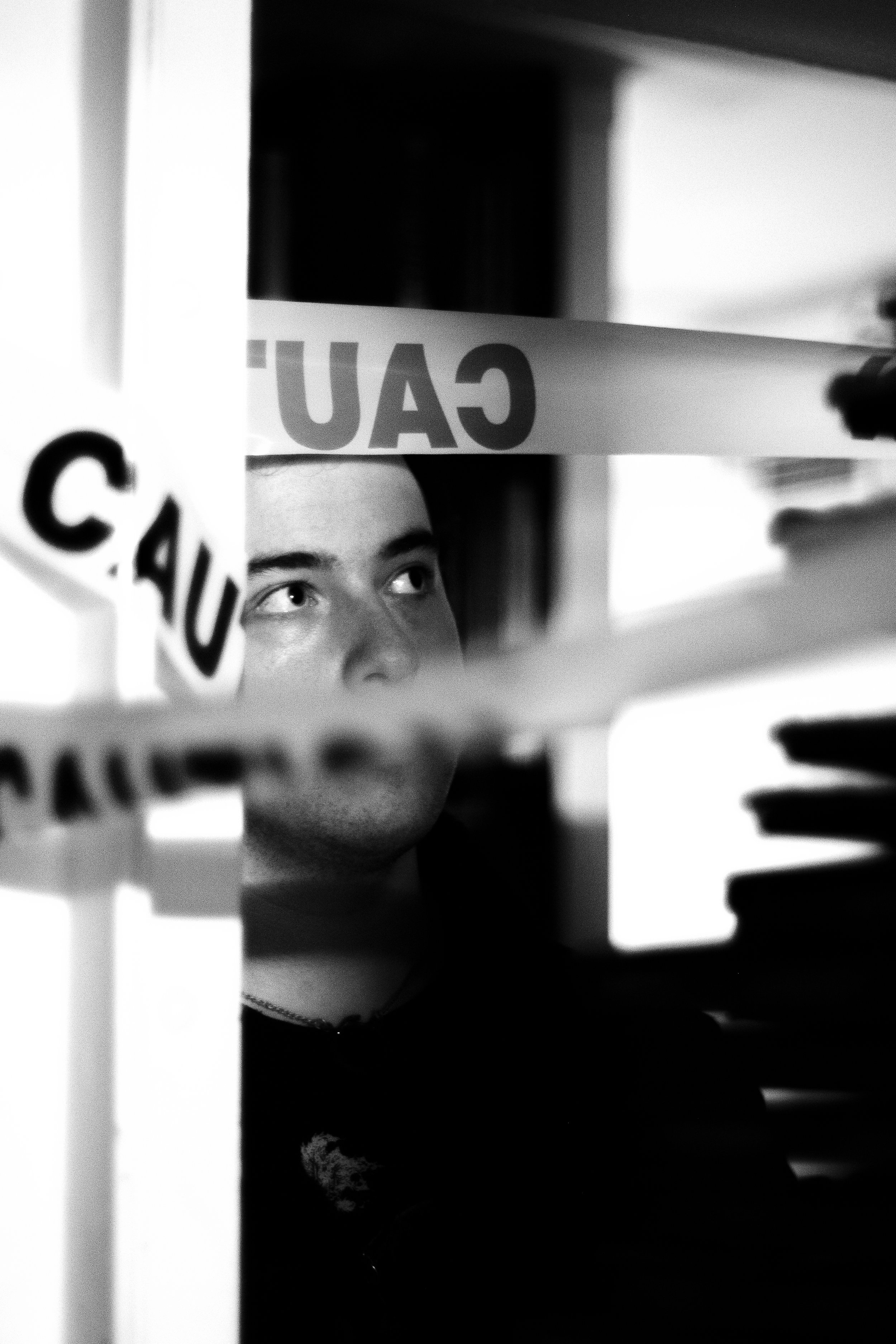

Self Portrait 2023, Shot 5

Through baroque and surrealist inspired settings and costumes, Norman photographs others and himself in these dream-like universes. “Some of my work is inspired directly by an artwork or an artist, and there's been a few times where I recreate them all together.”

Norman enjoys reimagining historic pieces of art while adding his own touch. In a photograph from Norman’s Couple Series, he takes a photo of himself and his boyfriend wrapped in a white sheer piece of fabric as they kiss. The photograph is modeled after the surrealist artist René Magritte’s The Lovers painting. His boyfriend is wearing a pink blazer, similar to the pink dress that the woman in the painting has on. “There's a conversation in that,” says Norman. “With other ones it's just like, ‘let's just do this, let's be in this world.’ So at first, it's about thinking of the aesthetic or the archetype, and then it's just about making it happen.”

Self Portrait 2023, Shot 4

Combining historical art with the present times interests Norman and is a recurring theme throughout his works. While Norman appreciates the freedom for self-expression in contemporary art, he believes that historical works still have a lot to offer in today’s art world. “A lot of contemporary art is trying so much to move forward that it's forgetting to include into conversation these really big pieces, and pieces that, as a student, I fixated on and admired so much. Bridging them with today's world is really exciting to me.”

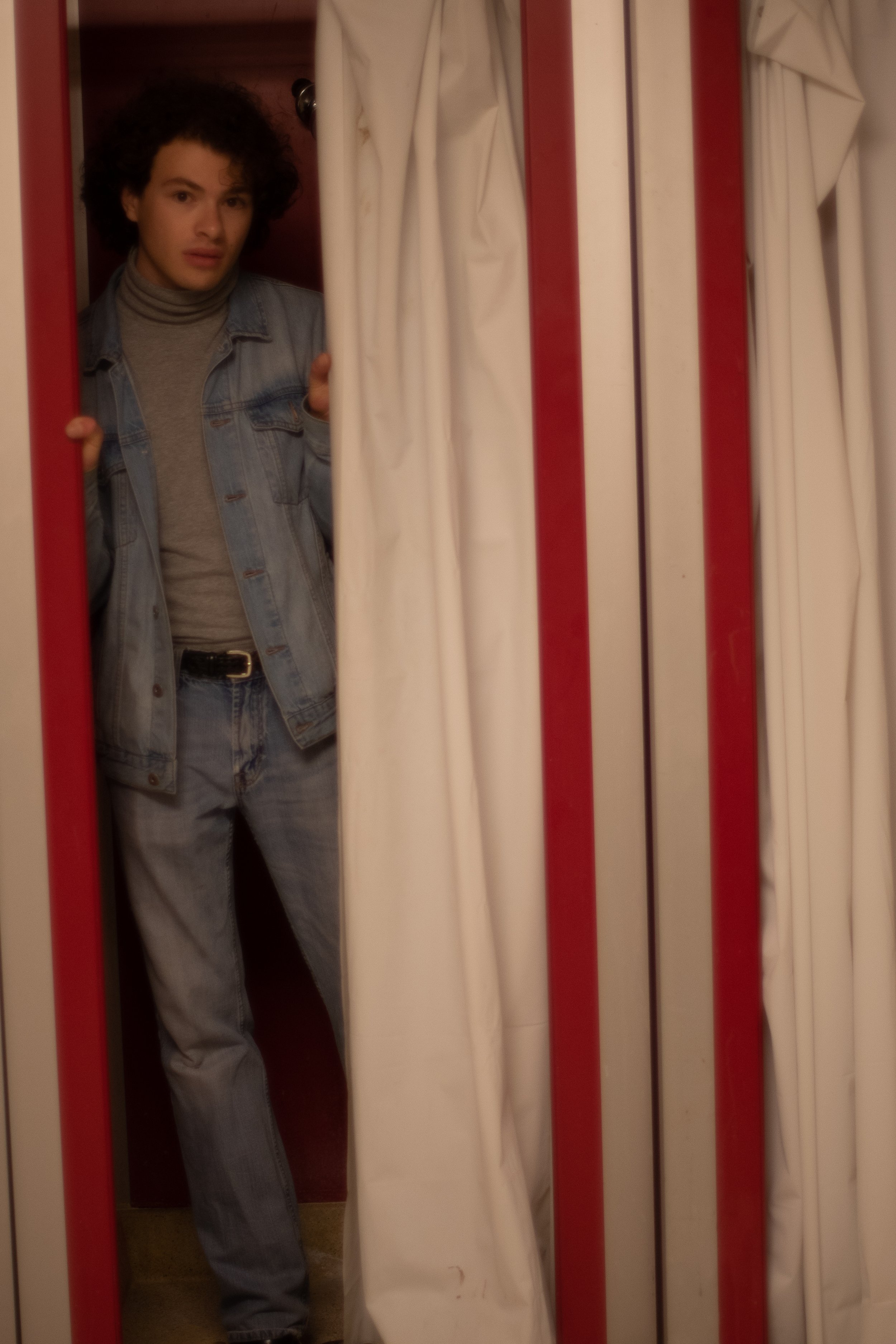

Norman enjoys revealing the inner actor or model inside of each of his friends and other subjects, and watching them transform into the characters that he assigns to them when he takes their photos. “I love seeing people, especially people that are not models or actors, really commit to their role and get a sense of being able to play. In my last film, my boyfriend was so anxious. He kept telling me, ‘you know, I'm not like an actor or anything like that’, so I fed him a lot of the narrative, which was inspired by Mary Shelley's Frankenstein. That was the kind of story that I was giving him; picturing that he's Frankenstein in this Gothic school, and he's already created the monster but it's lurking and he doesn't know where the monster is, it creates the sense of anxiety that at any moment, the monster could pass by. My boyfriend really committed to it. At one point he was almost panting, and I loved it. I love seeing people really commit to these fictitious characters and have fun doing so. I liked seeing them after they realized who they became or what they were embodying.”

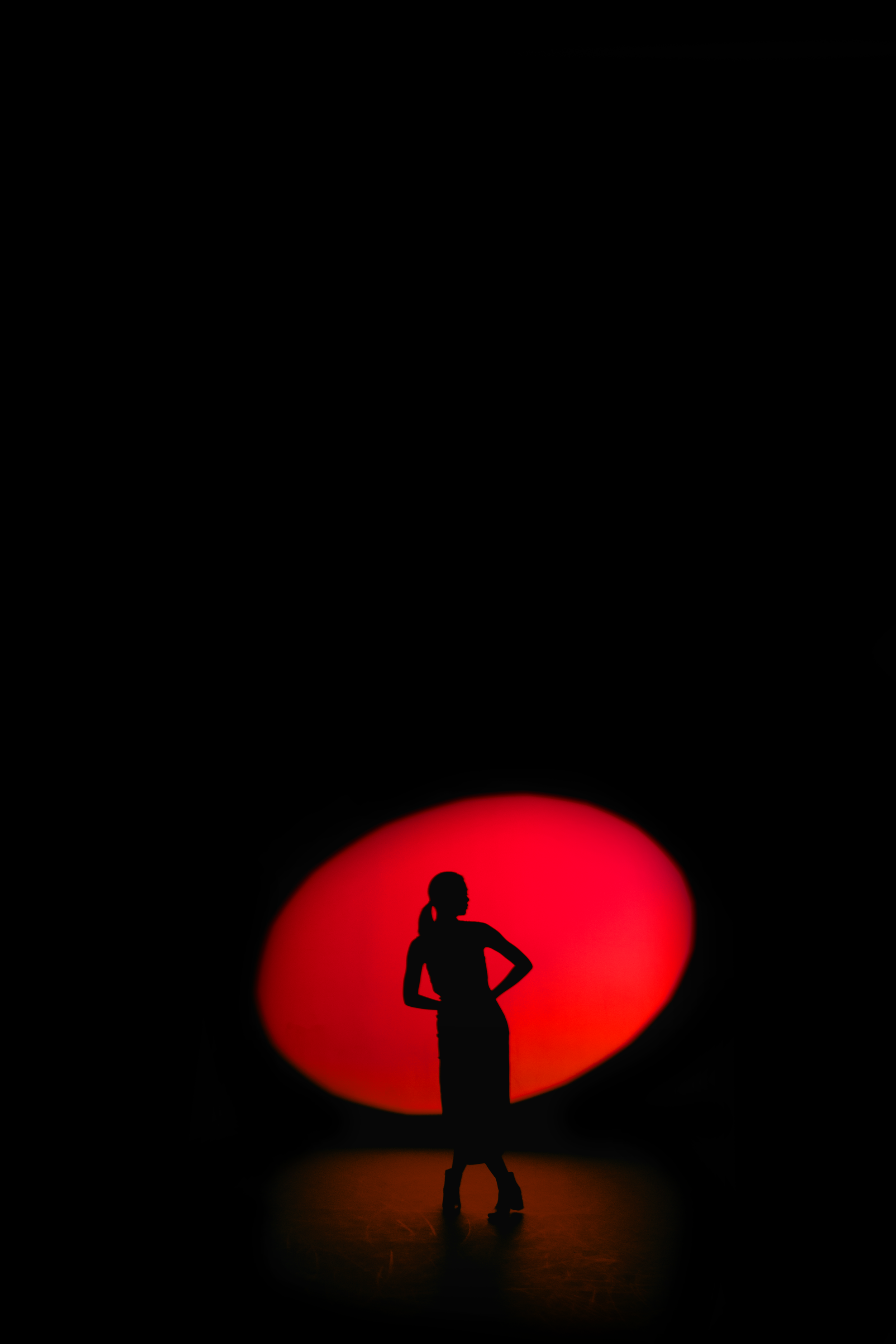

Chiaroscuro, 2021

People’s abilities to create their own worlds and decide how they’re going to present themselves in it sparks Norman’s love for the moment in history in which we live. Norman believes that people, and especially Columbia students, are no longer restricting themselves to binary ideals of the past and this inspires his work. “I'm just inspired by radical people,” Norman tells me. When he first got to Columbia, Norman focused on spending as much time off-campus as he could to try and explore more of New York, but this year, he’s come to appreciate the community and the people on Columbia’s campus. “The kids are cool!” Norman explains. “I'm excited by people doing their own thing and what it looks like today, which is very different. Seeing people lean into their own is really exciting to me. This includes gender, sexuality, self expression. I think gender is a big one, but also just personal aesthetic. I've seen people dress in 70s mod to class for no reason, which I really enjoy.”

Self Portrait 2023, Shot 2

In addition to the narrative driven worlds and Baroque inspired scenes that he captures in his photographs, Norman enjoys taking polaroids to capture day-to-day moments. “The reason I love polaroids so much is because I give myself a limit. If I go out with my polaroid it usually has only eight photographs. Sometimes I choose not to bring any more film. So when I’m going on a weekend trip or a week trip I only have eight photographs.” This allows Norman to focus more on waiting for the right moment to present itself, instead of trying to make something happen.

Photography has been and remains Norman’s primary medium. “I just like photography,” he tells me. “I like how it can be meta. There's this series that I’ve been thinking of doing where I would take my own portraits, shooting myself in different time periods. Today, everything is photography, and everything is a digital image. I think that there's a lot of conversation in that, a lot of ways to be really meta about it, which I would love to get into.”

Normans, 2023

You can find more of Norman’s work: @normin_norman and Norman’s portfolio.