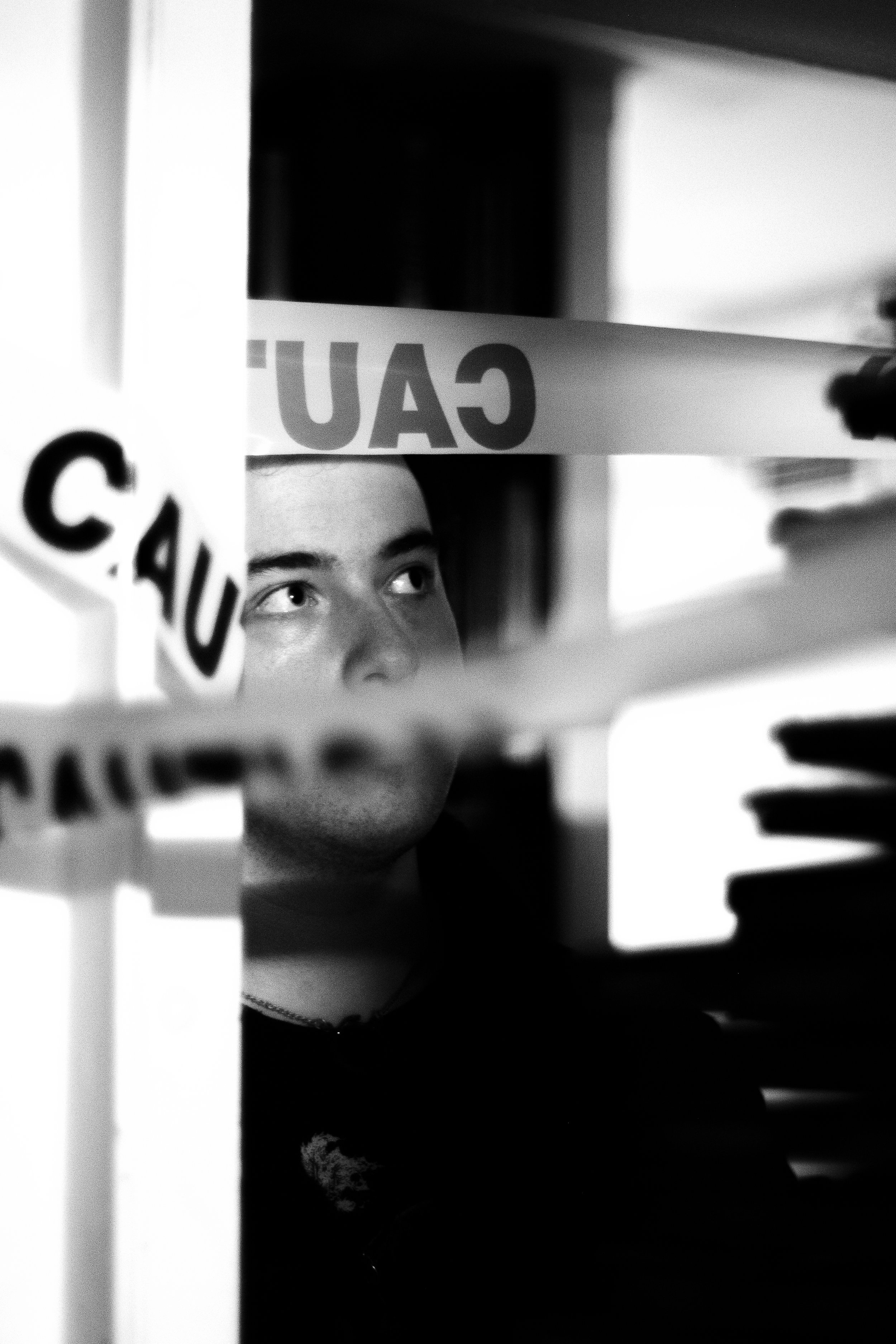

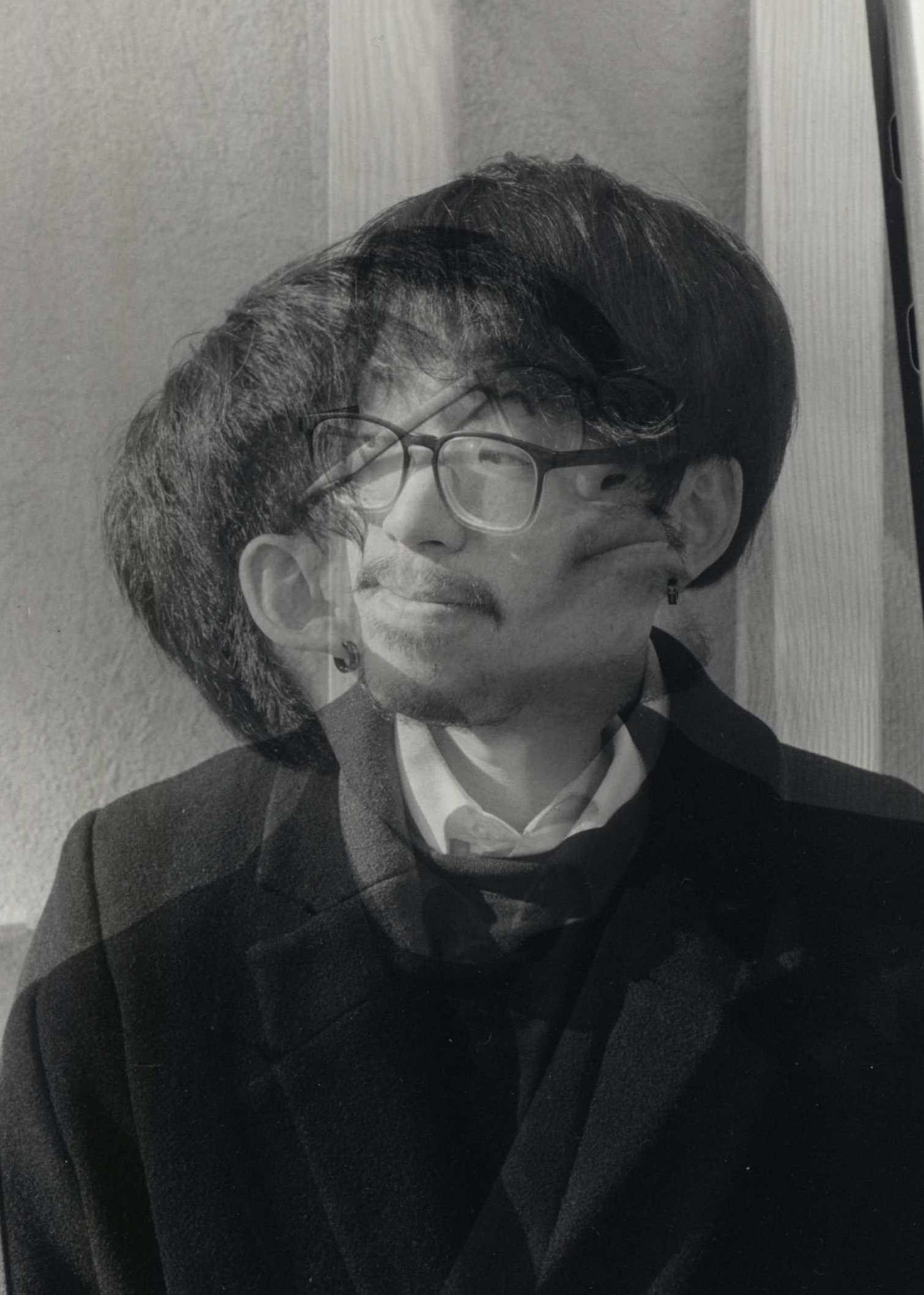

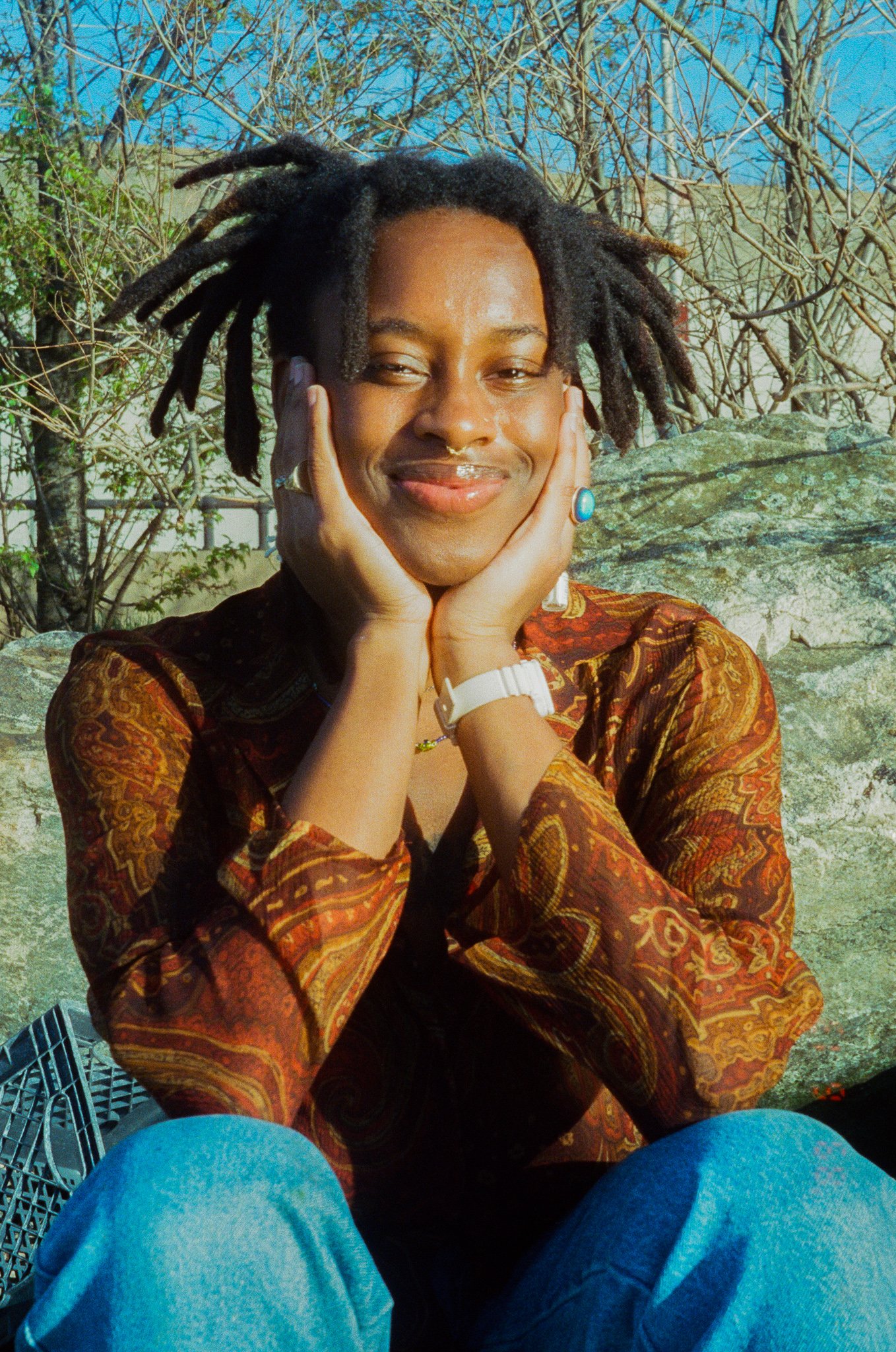

Feature by Claire Killian

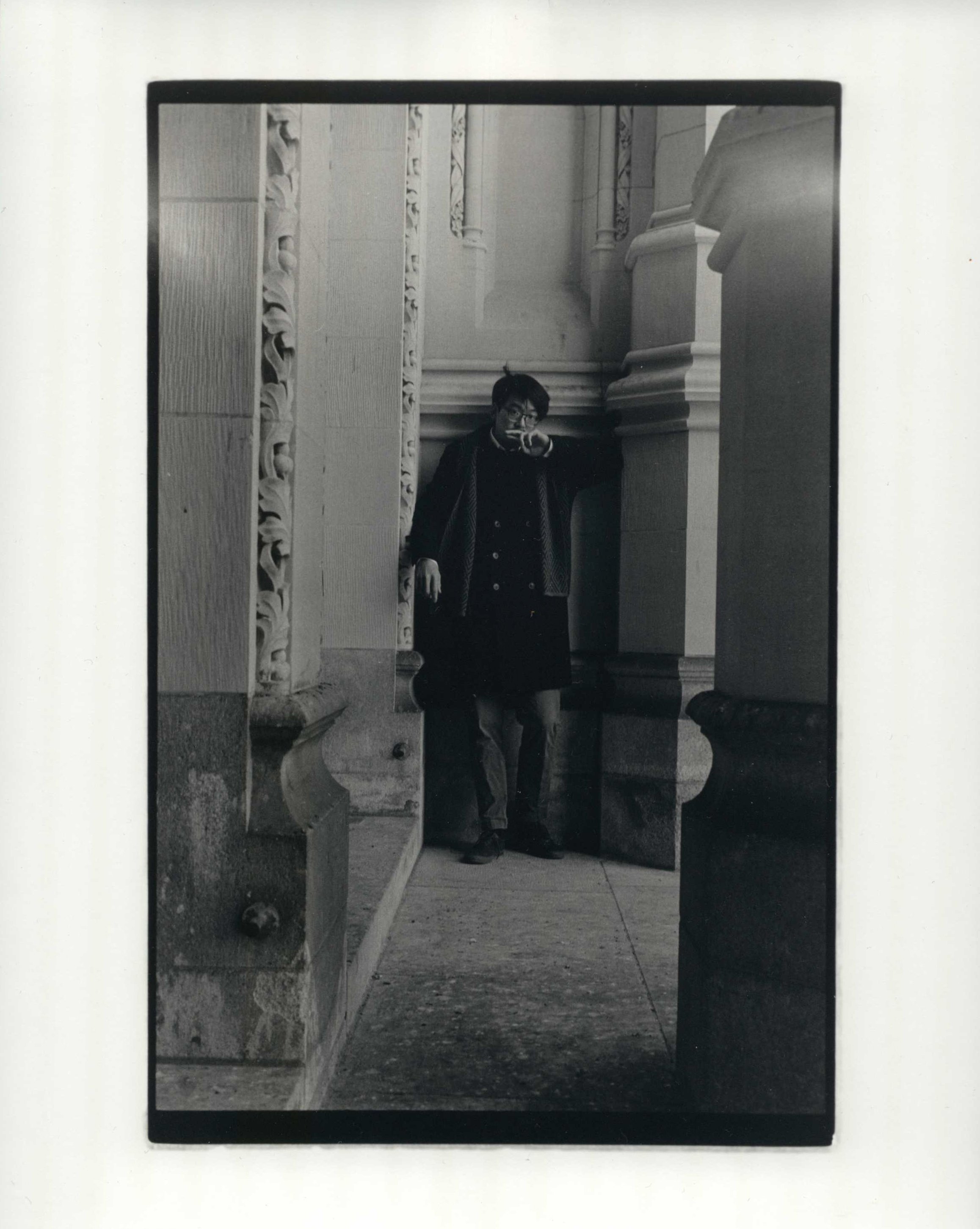

Photo by Haley Cao

You say that you didn't really start identifying as an artist until recently, you considered yourself more of an engineer. With that transition, you talk about there being an overlap between the two. Can you speak to the dynamic between those two identities?

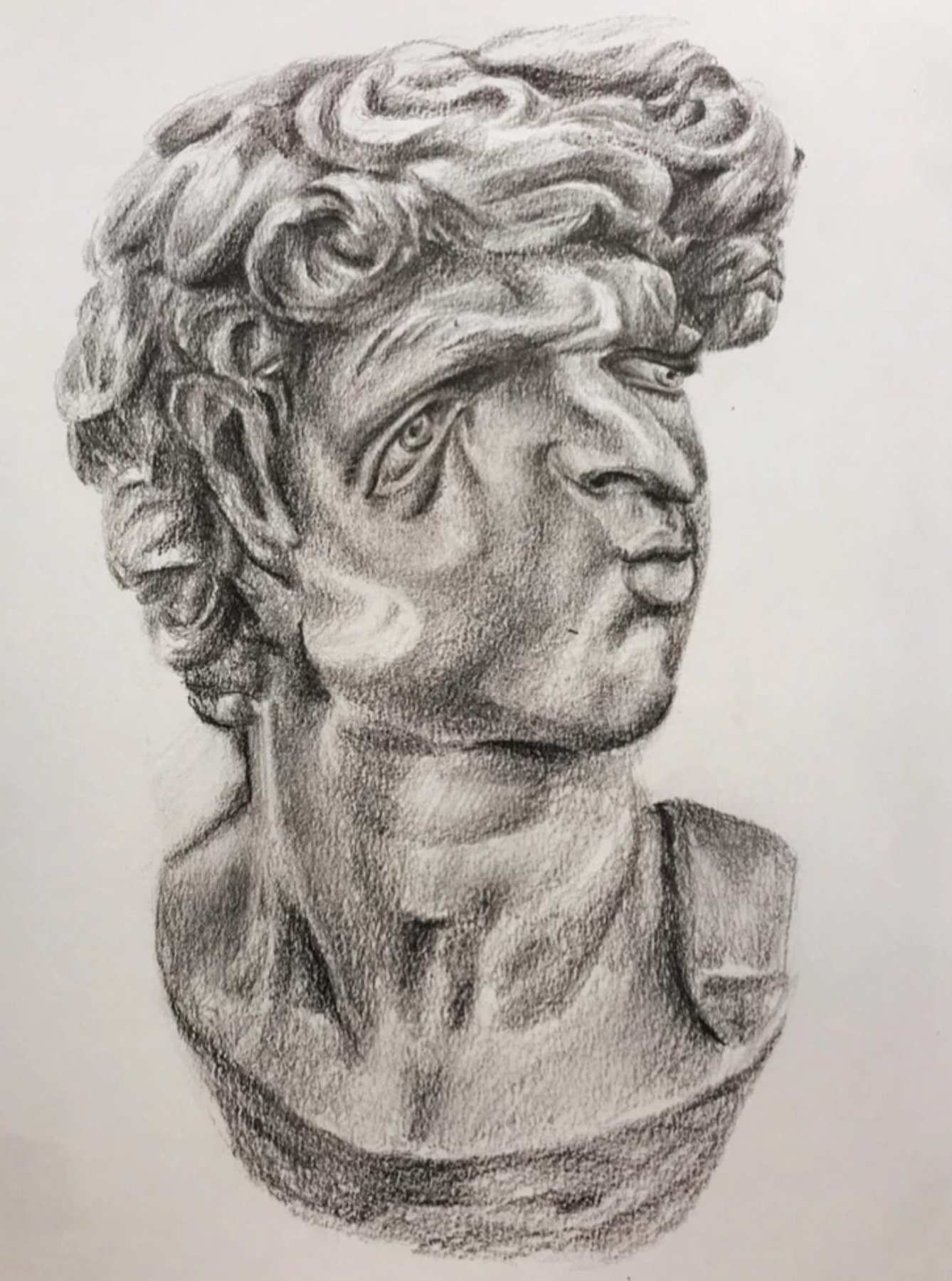

To be honest, I didn't really even consider myself an engineer for a while, because I was still very much seeking to understand the mechanisms behind whatever we're building. But that aspect of building is what drew me to engineering in the first place. That is what really falls into art as well. What took me so long to consider myself an artist/fall into the process of making art was the process of making, I never really felt like I was creating something new. And because I was so into photography, for a while, it felt like I was capturing something instead of positing into existence, but there's an overlap in my eyes, because a lot of the process is just making something exist. It's like, this is something that is observable, it's something that is a feeling, it's something that is something that is an idea. How can we actually construct it and show it and share it?

In addition to art and engineering, there's a third component to your work - you're in an acapella group! Music factors into what you do very heavily. How does that add to the dichotomy between art and engineering?

Music has been there for me since day one. Growing up I didn't really have artists in the family. My mom was a literature professor, and my dad does engineering work. They're immigrants, so they never really assimilated with American pop culture, but pop culture was what drew us together. Music, movies, all that stuff was what drew conversations between all of us, which, going back to music, was something that was unspoken but it could be spoken, just a way of creating fluid conversation for us. For me, music has been that through-line where it can both be nonverbal and a verbal expression of how we're feeling. That honestly ends up being a lot of the motivation behind a lot of my work. A lot of my drawings are made by listening to something and I'm trying to process exactly what's going on. But it manifests in a visual way. Photography wise, I started using cameras, because I was going to concerts and taking photos for artists. Slowly I realized that it was detracting from the experience. So eventually I was like, ‘let me put it away.’ But it's how I trained my eye in a live setting. As for a capella right now, I've been in it for all of college so far, and it's just been a huge community for me. It has also constantly embedded me in this acoustic world of singing with my friends. That feeling of blending is really powerful, but has also shown me the power of our own voices and expressing what's going on.

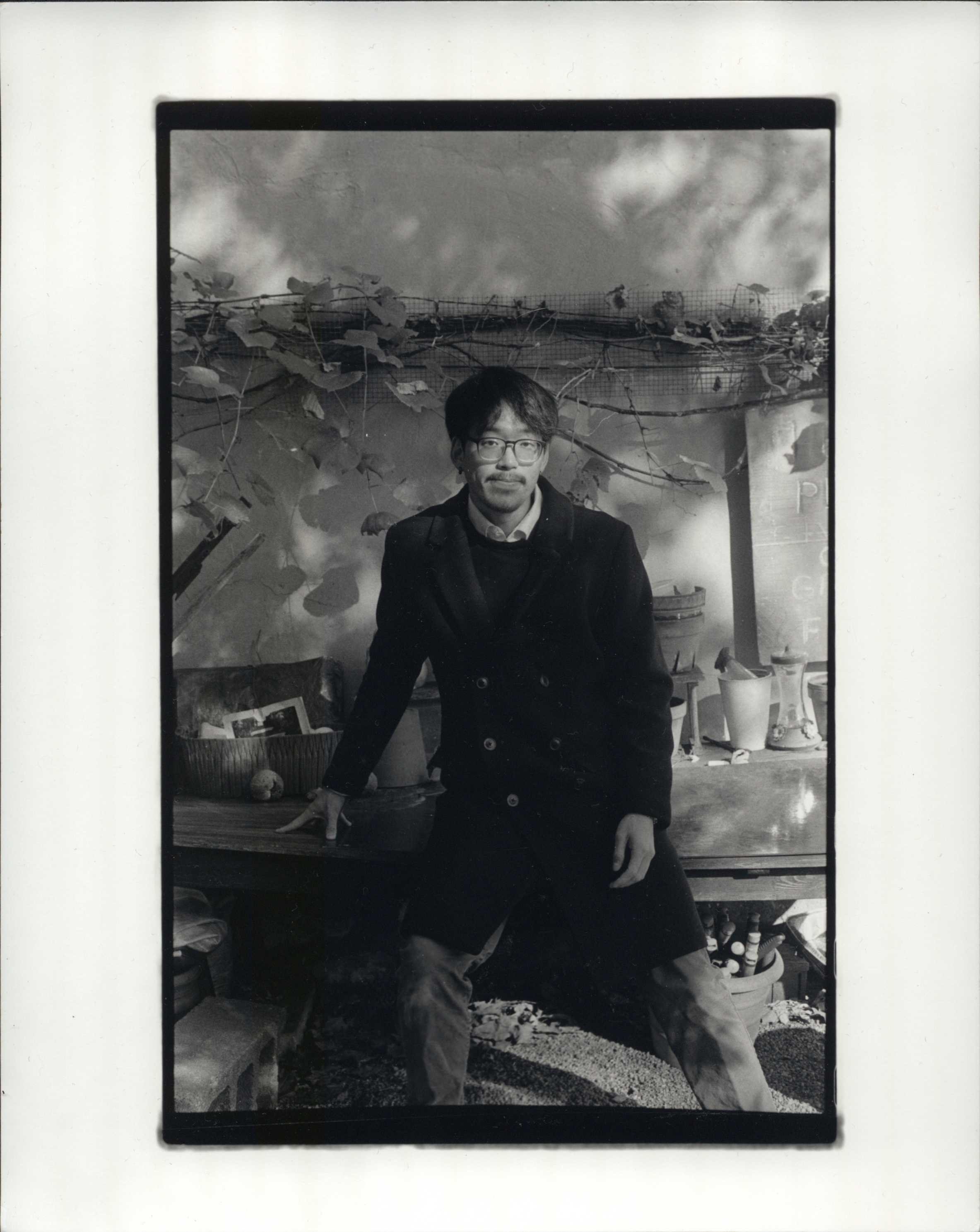

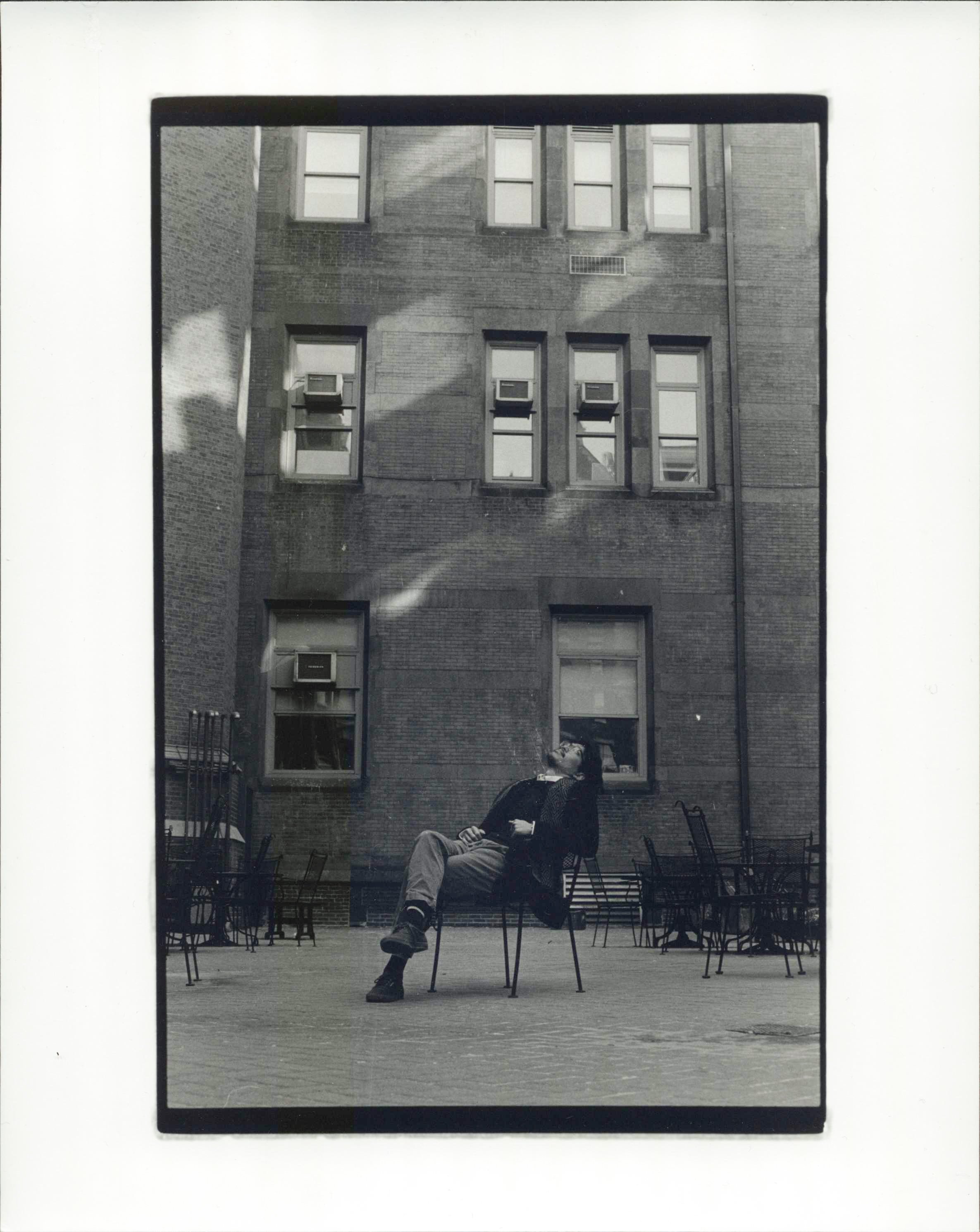

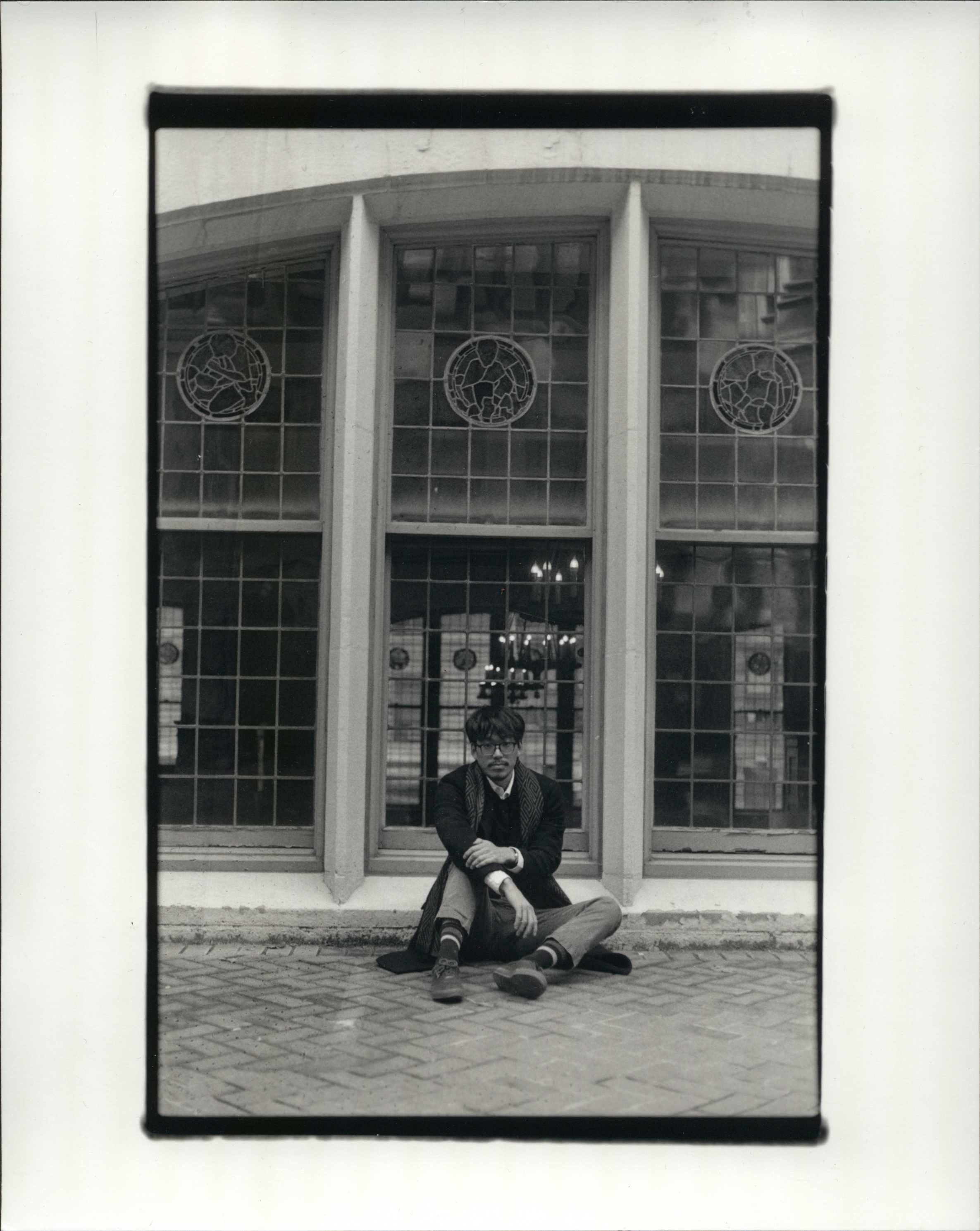

When you have a camera in your hands, and you're in any sort of environment, whether it's a concert, or you're out for a walk, what is the catalyst that makes you lift the camera up to take a picture? What are you looking for at that moment?

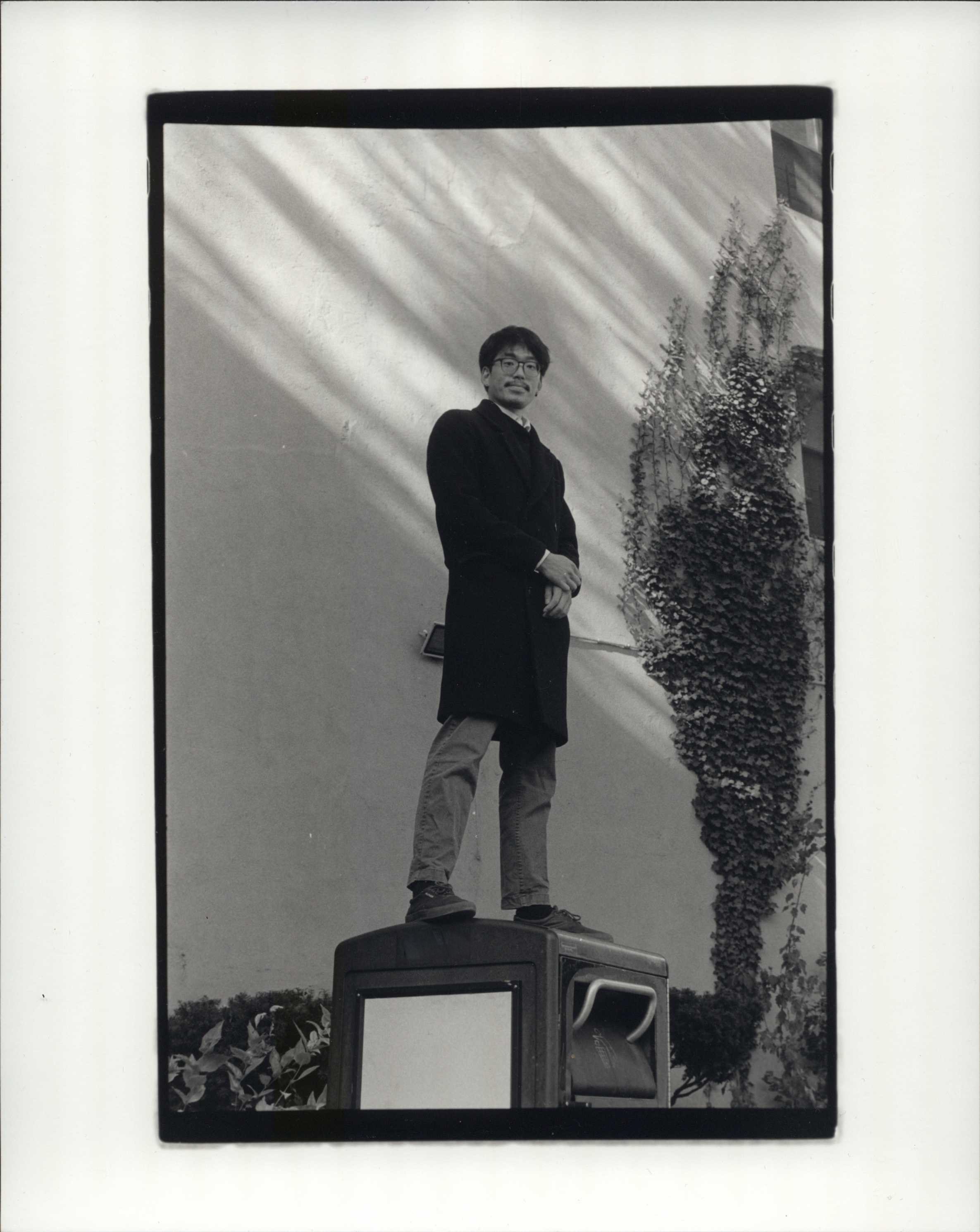

For me, it's not really conscious. It's a very knee-jerk reaction, where I see something that kind of sticks and I need it to stick, so I pick up a camera and go for it.That style changes a lot depending on what type of camera I'm using. I'm sure all of us were like this, but growing up with phones, the first camera I ever picked up was an iPod Touch, and that's how I got started. Moving into college, I got really into film, and film felt a little bit more intentional because it was like, ‘I only have 20 shots and I'm here with my friends, and I brought my camera with me so I'm gonna take a few pictures here and there.’ It's definitely a feeling of capturing a moment for me - we're so caught up in the flow of everything that photography, for me, is like taking a step back and thinking ‘alright, this is a little scene or a little frame of my life movie that I'm trying to capture.’

You talk about using a ton of different mediums. Obviously there's photography, and then within photography, there's film, there's iPod cameras, there's everything. However, you also write about VR simulations and music visualizers. What are those?

Those were interests that came to me during COVID. We couldn't go to concerts, movie theaters were shut down, and I had always looked forward to those little, real-time environments. In those places I always felt like, ‘I'm sitting in a room. I'm listening to music. I'm watching a movie.’ I felt very present in those spaces. I tried to look into ways of replicating that in a remote setting, and that ended up falling into virtual reality and music visualizers. V.R. was actually pretty embedded in a research project that I've been working on since freshman year. It's been a four-phase study, where every year we take in hundreds of people who come into the lab and play a video game. It was actually a simulation of Apollo 13, where three different people are trying to get back to Earth in time because their spaceship’s dismantling. They each control a different part of the spaceship and they have to coordinate. I've been running that experiment, and I built the environment to simulate it. It gave me a lens for digital architecture. There's so much talk about the Metaverse these days, and how it's going to reshape how we work with each other, and how we interact with environments - that environment is entirely constructed in virtual space. It's man made, but it's also electronic, and it doesn't feel necessarily authentic, but it's supposed to. What drove me was this question of, ‘how can we create those spaces that feel real even though they’re virtual?’ Then with music visualizer, literally through all of middle school and high school I would just go to concerts all the time. I was really big into EDM and electronic music. A lot of the artists that I saw would put on live shows and they'd be out there with synthesizers and their keyboards, but in the background there would be a huge light show. It was so beautiful, and it added so much to the musical experience, that I spent a lot of time learning how to code visualizers and worked with some friends on designing interfaces with them. It’s definitely an interest of mine.

Just listening to you talk, it sounds like space and community is so central to what you do, whether it’s talking about going to a concert and wanting to capture a moment, or being in a space and seeing this amazing light show, going on or even just trying to construct a virtual space. When someone interacts with a piece of art that you've made, if they're looking at it or they're literally experiencing it, what sort of experience do you want them to have? Do you want them to come away with anything? Do you want them to feel any particular way?

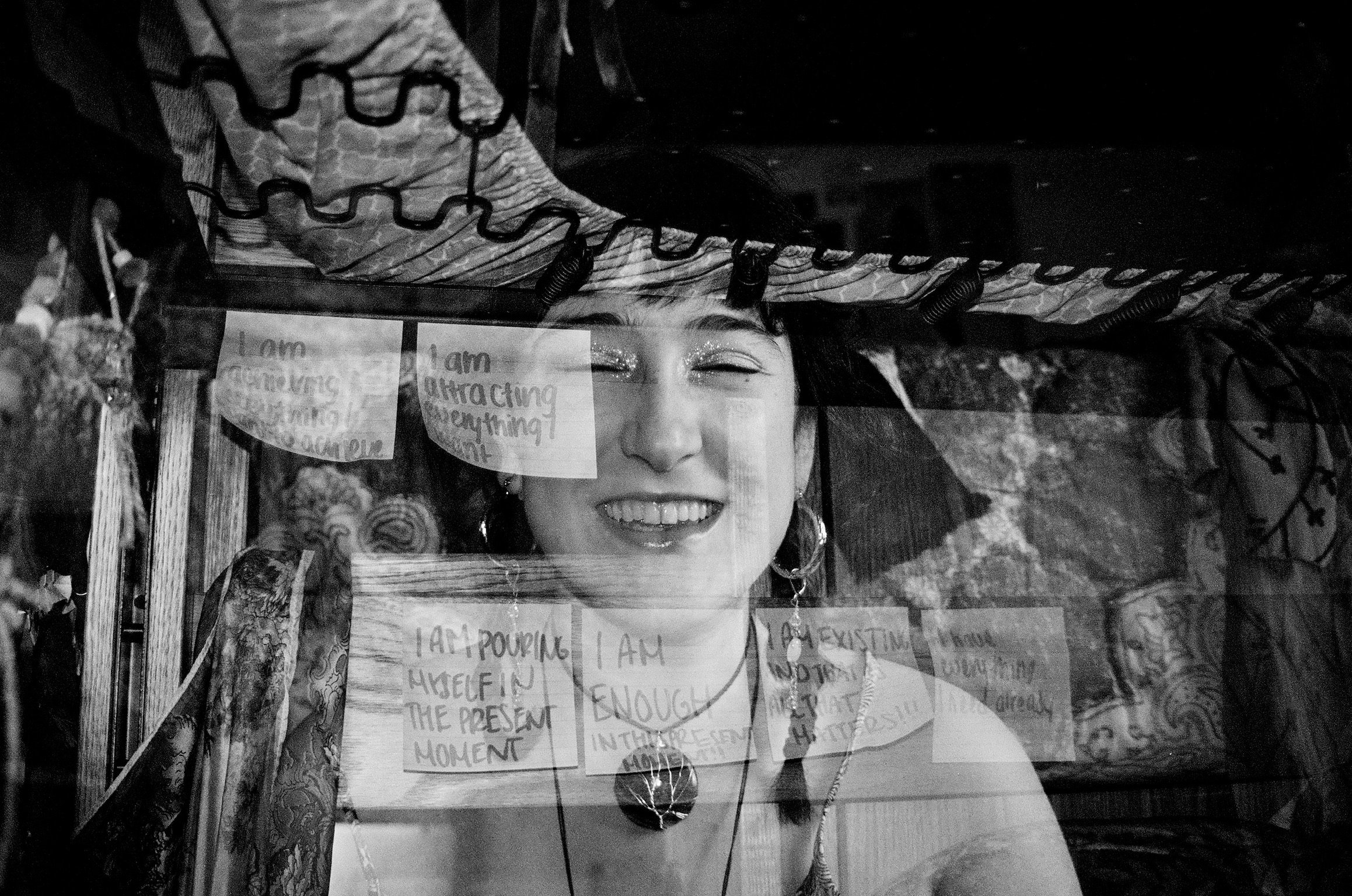

What made me fall in love with concerts and those shared spaces was that feeling of communal empathy, the feeling of, ‘I'm a part of a group of people that are all immersing ourselves in what this feels like, and running with it and flowing with it.’ One big piece of what I would look for in someone trying to experience my art, per se, would be perspective - what do you see in this work? And yourself? And what is being reciprocated? What might you see in an artist's work when you're doing that? Because we go to concerts, and we hear people sing deeply personal things, and you resonate with them. We flow, and we dance, and we sing along. It's them sharing and us sharing back, it's a constant transfer of energy and light. I would hope that by sharing our own works we also share insight, that level of mutual understanding or introspection.

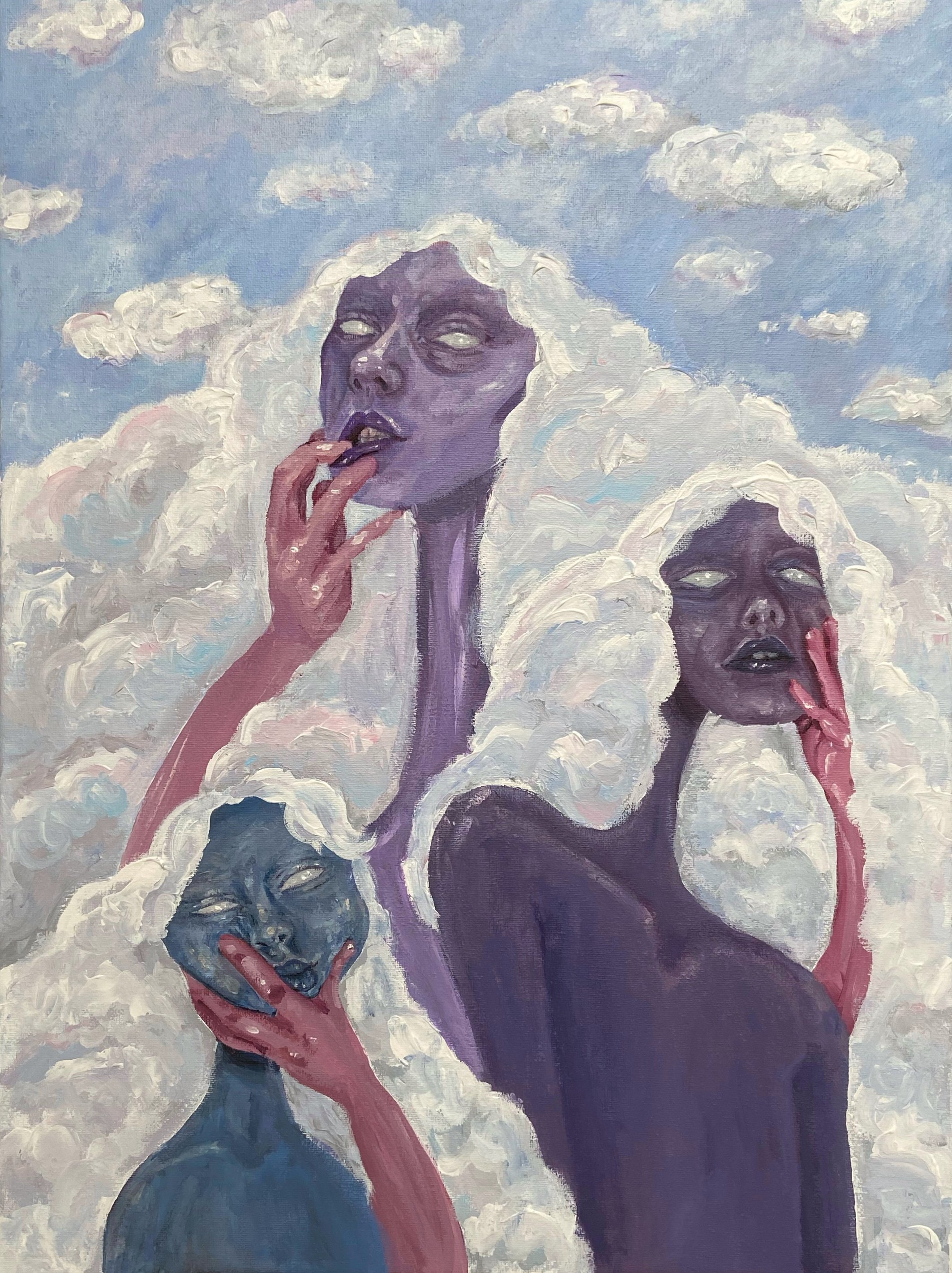

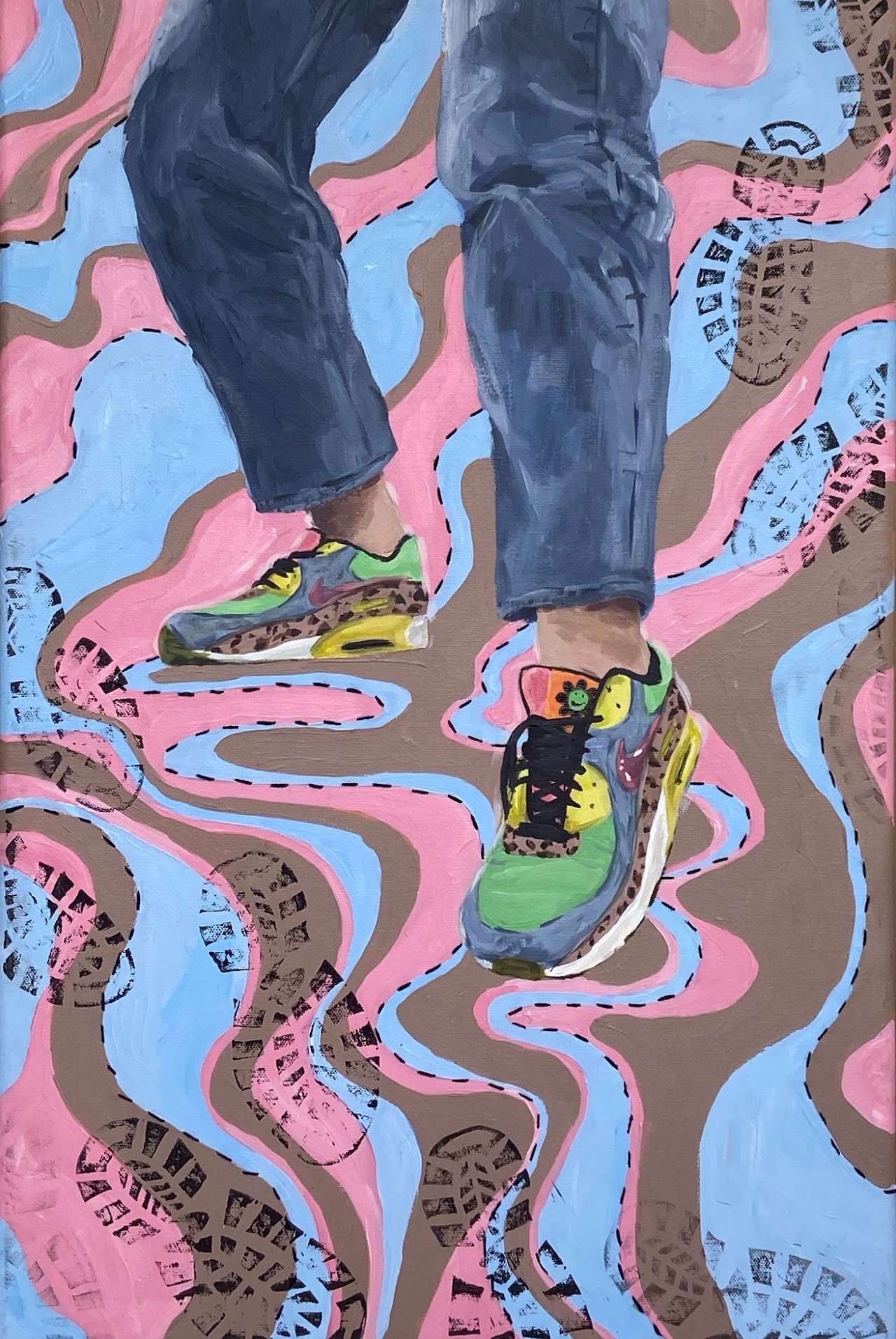

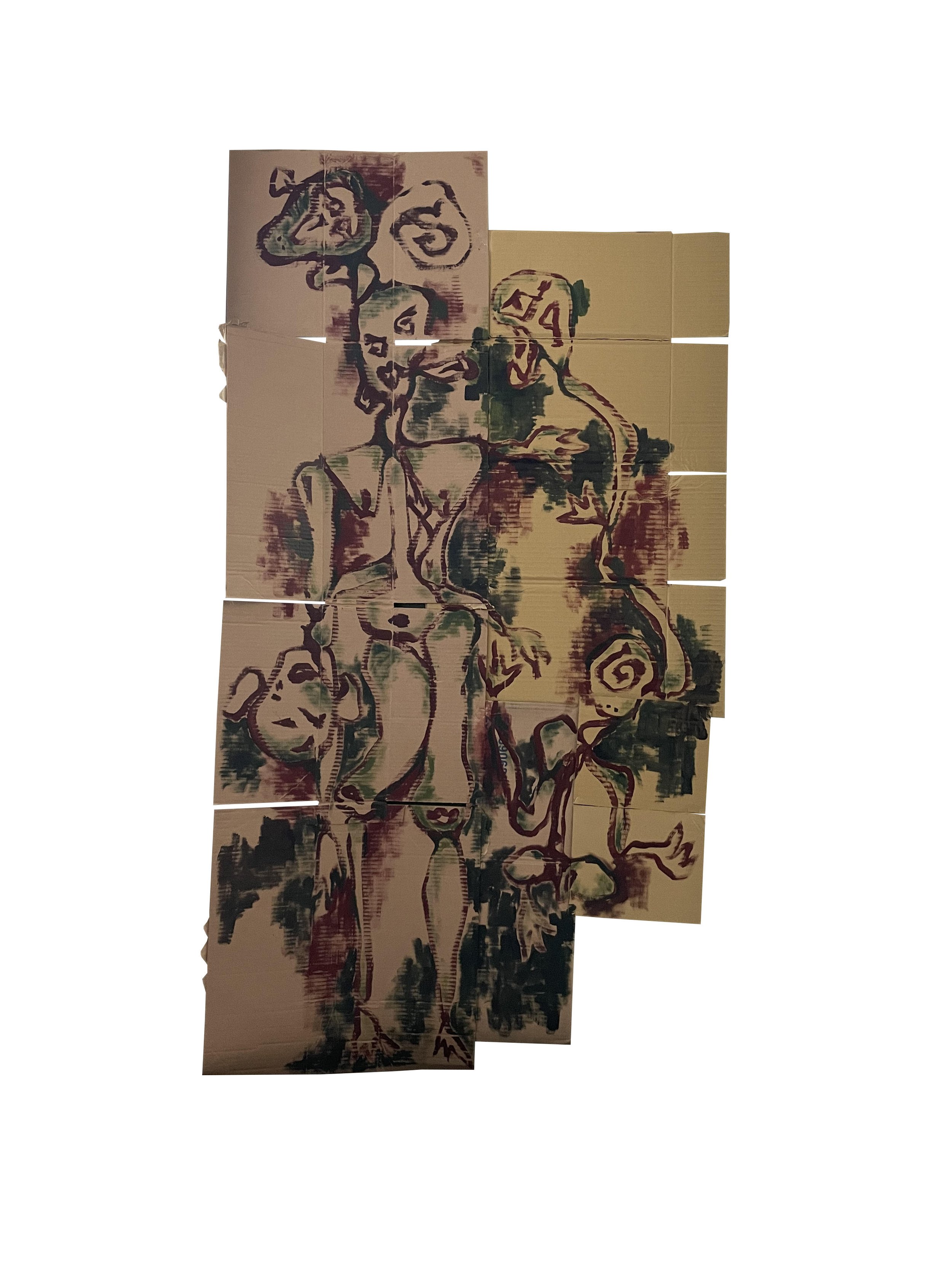

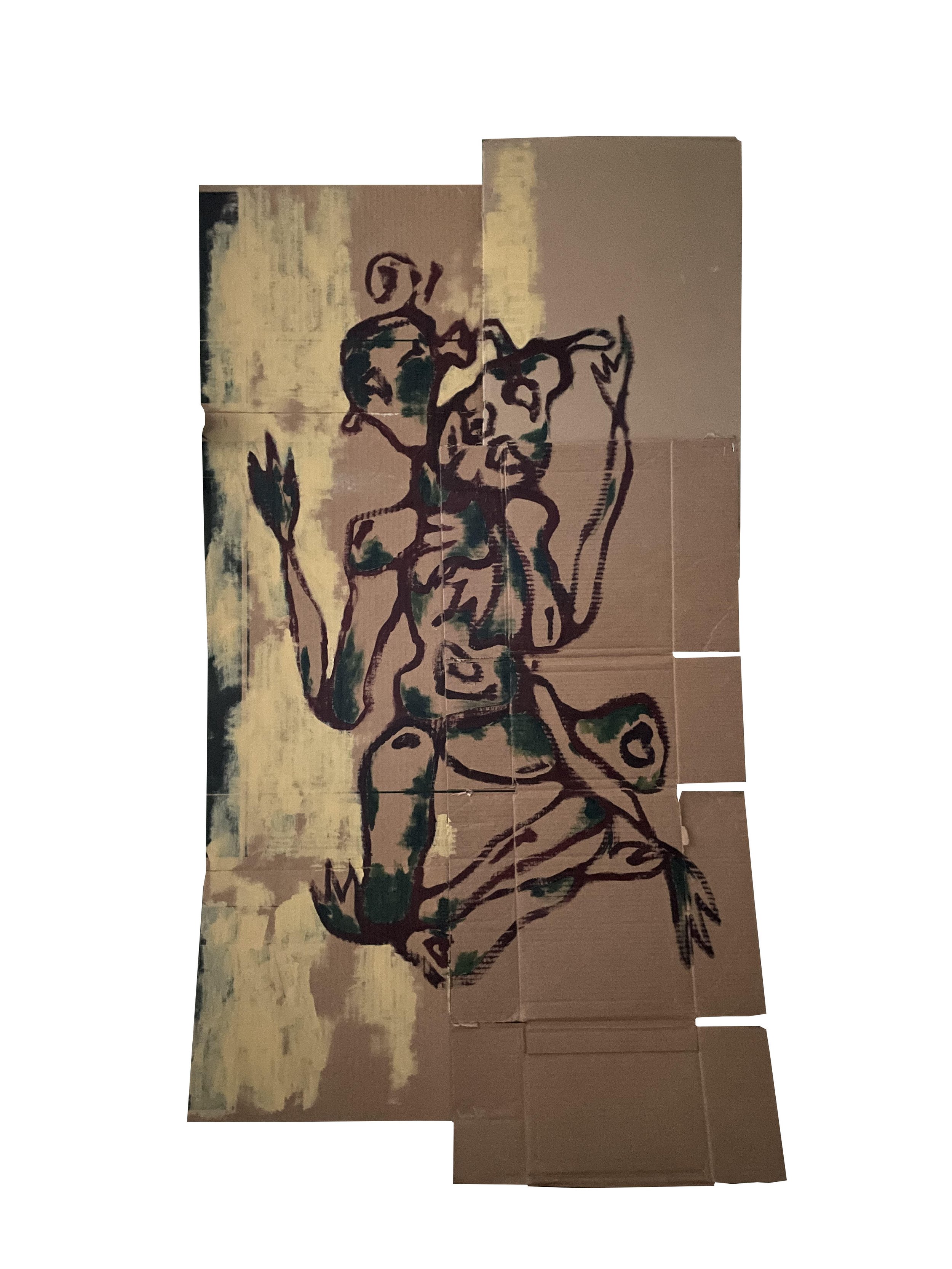

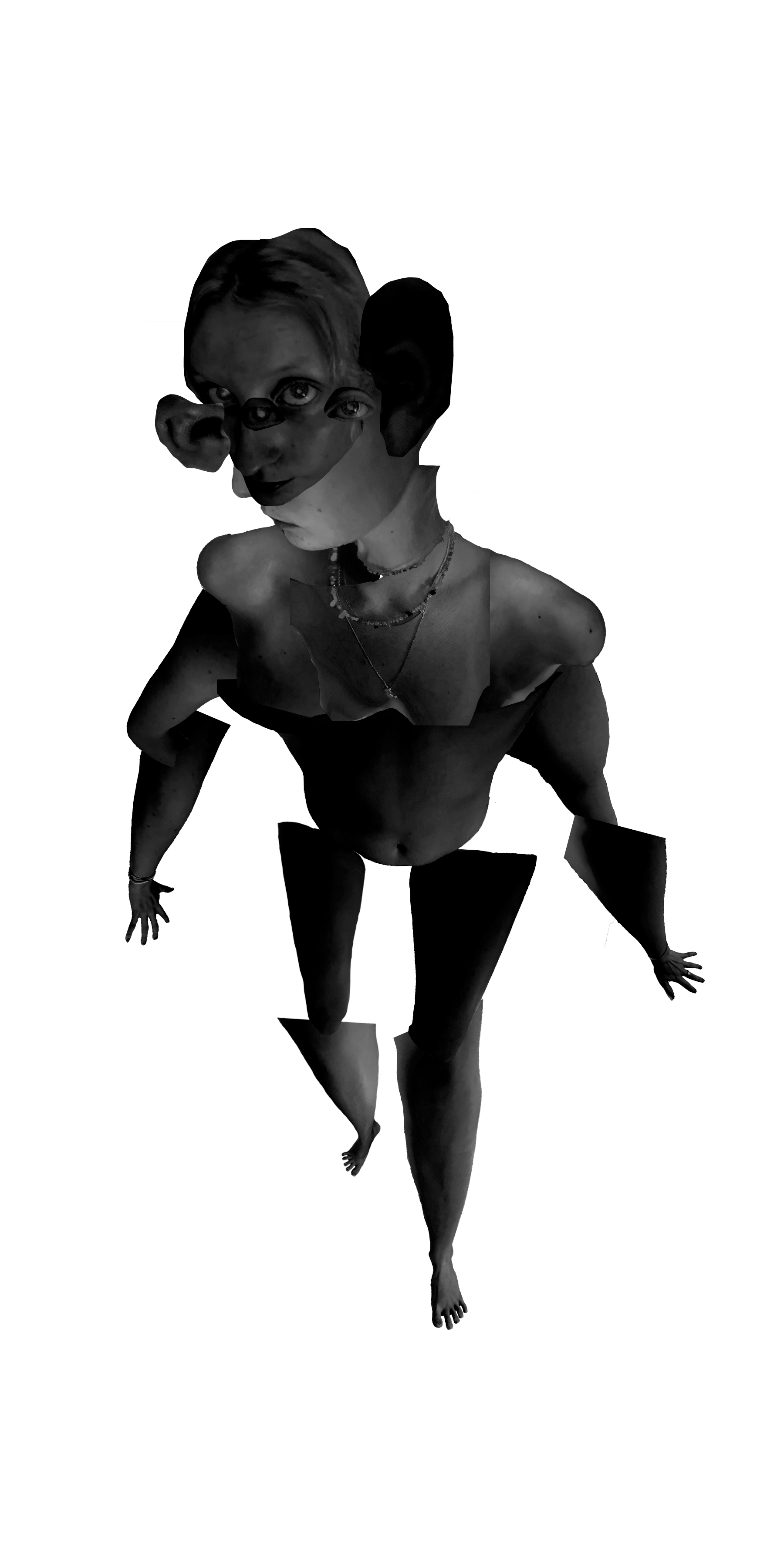

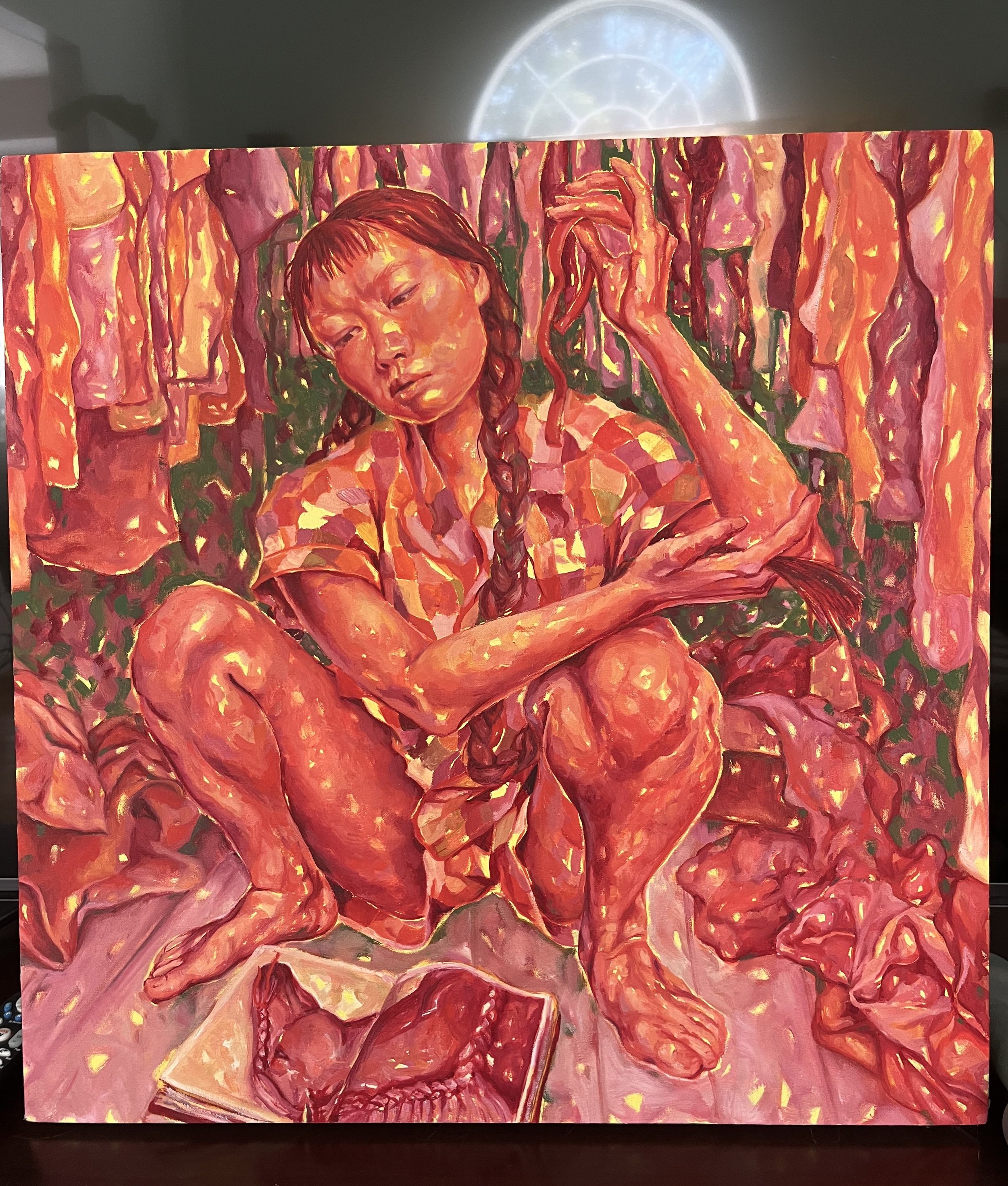

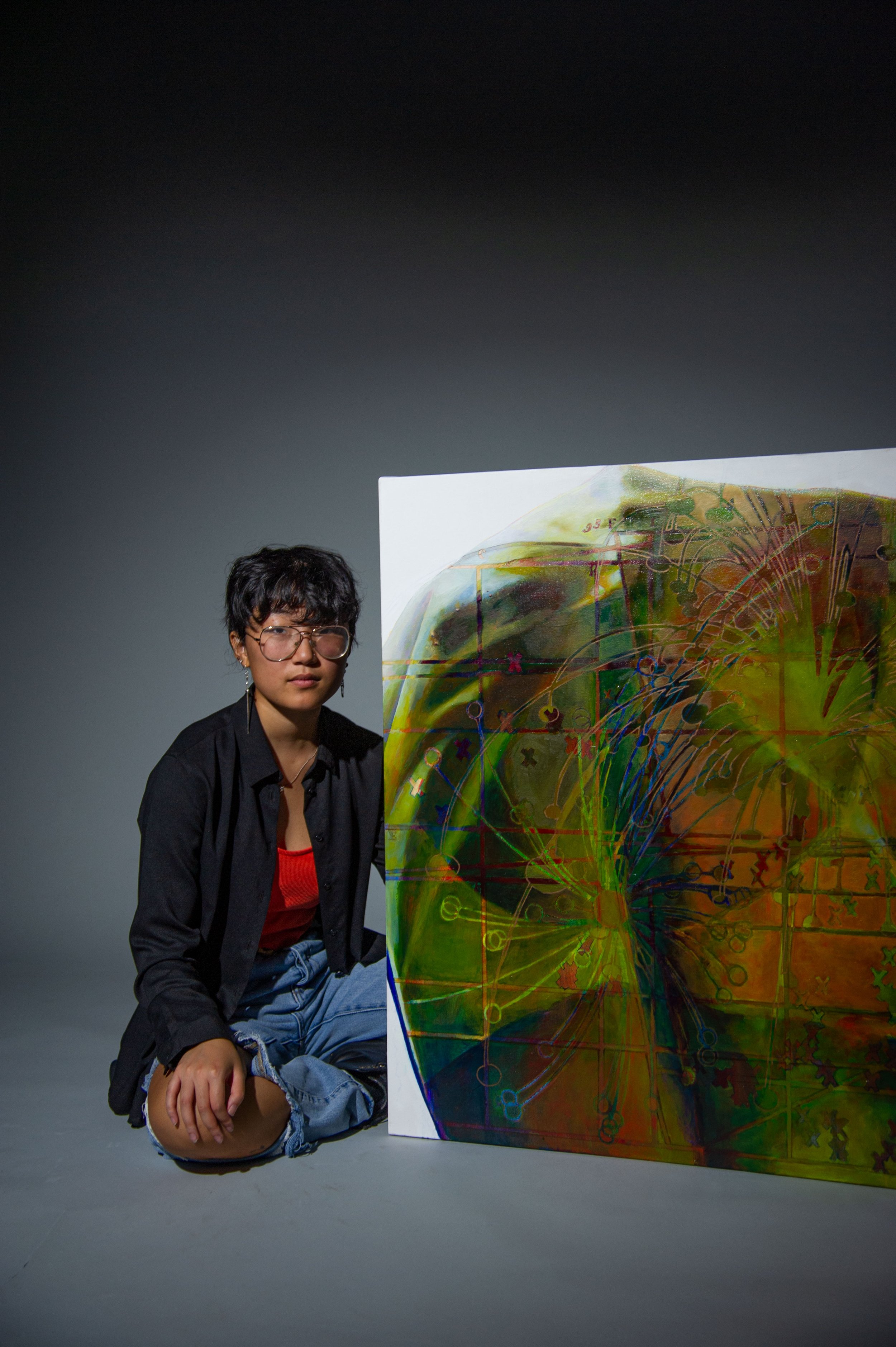

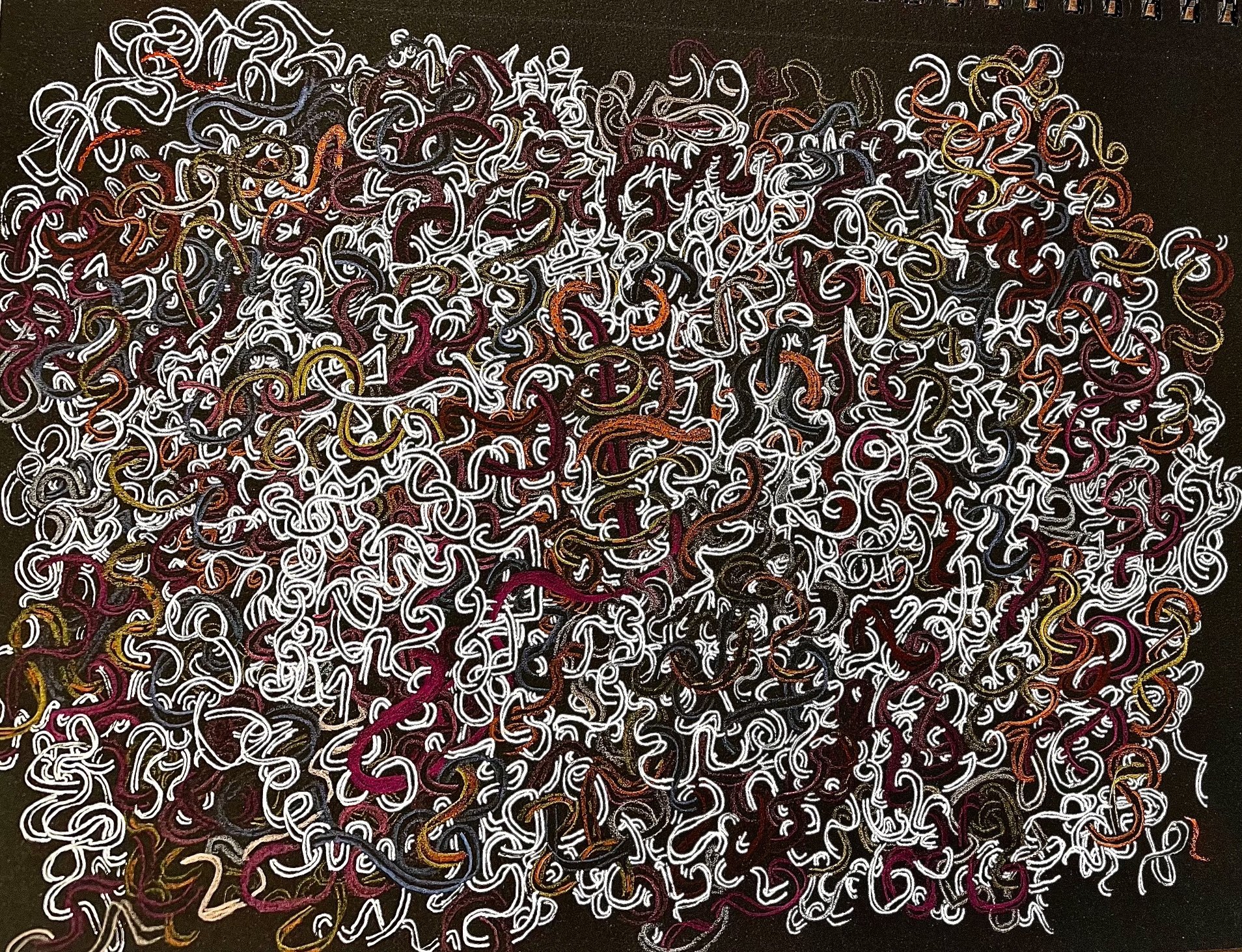

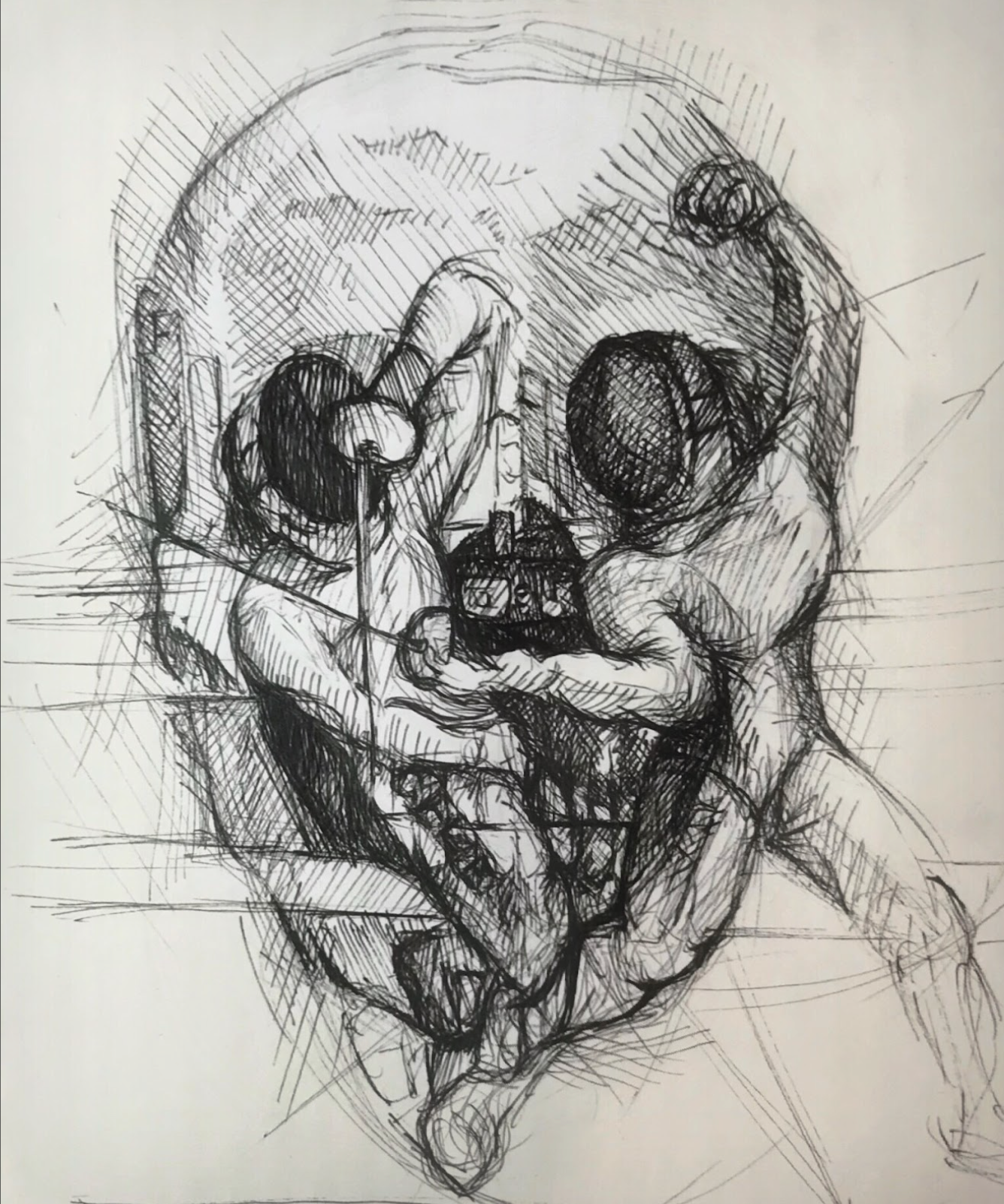

Your work is predominantly digital, it’s largely based in engineering, and so much of it is about the give and take between people in those high energy spaces, like a concert. Then there's one set of pieces that are so much more analog, that are cerebral and introspective, and more focused on you. Those are the doodles! I'm really curious to hear from you about them, because, at least to me, they're so different conceptually from all of your other work.

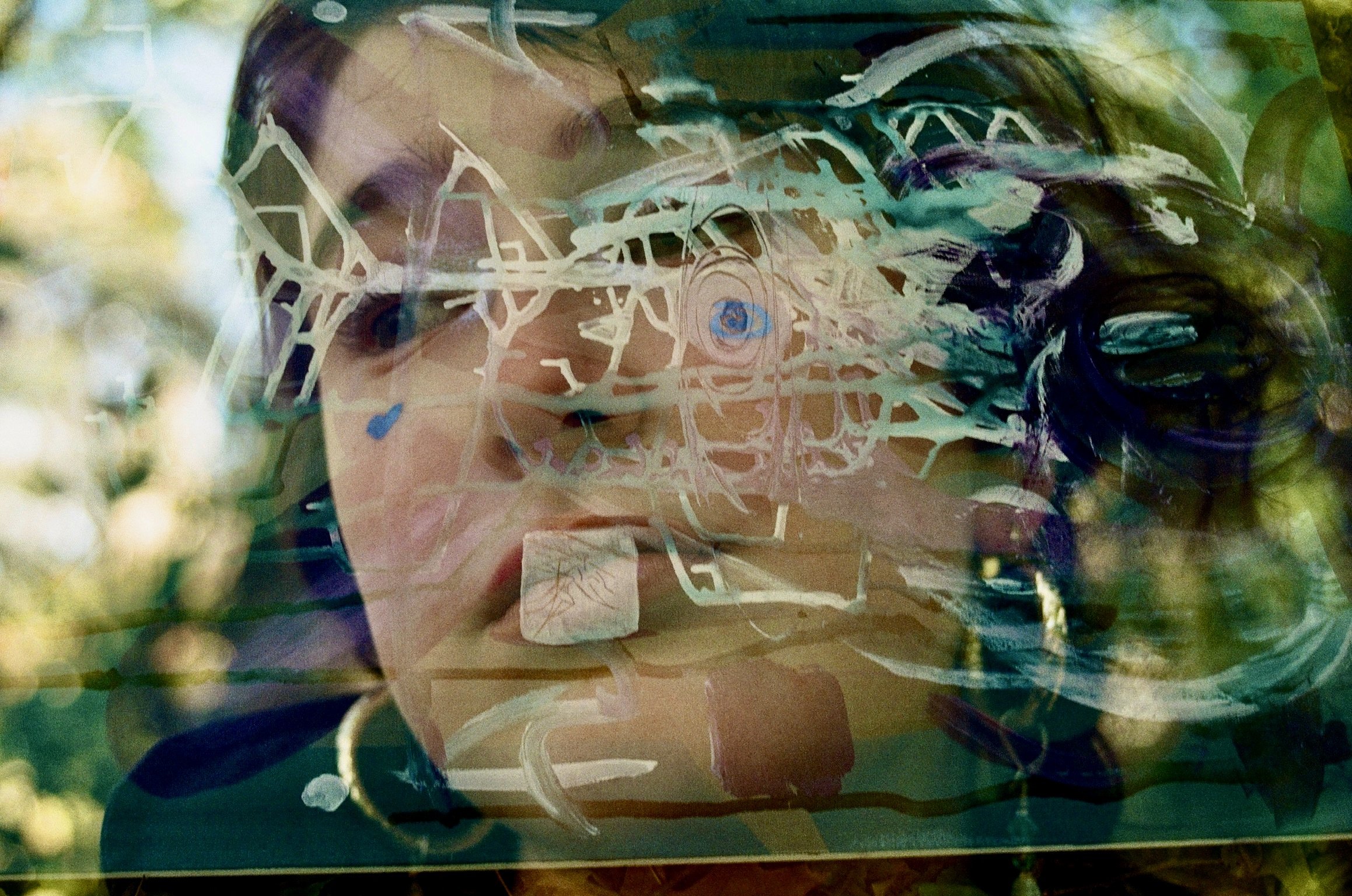

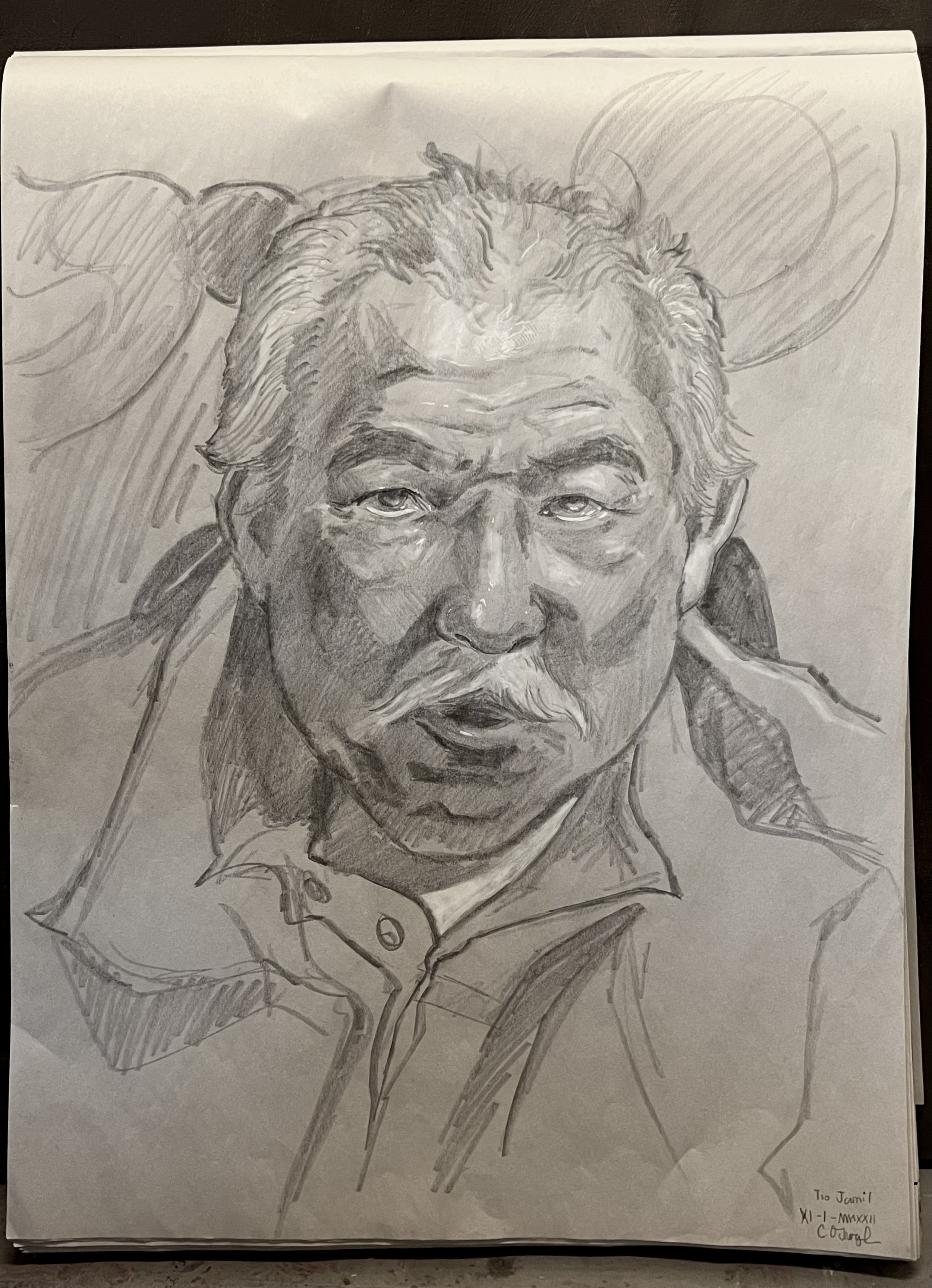

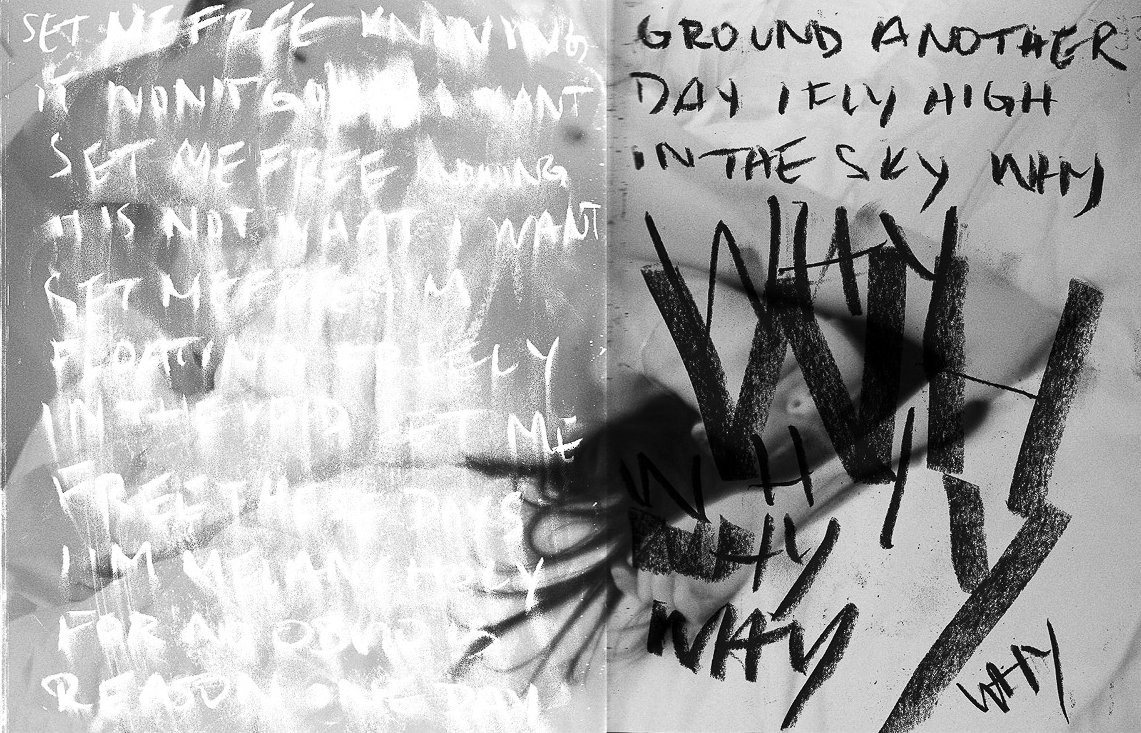

For the longest time, a lot of my work was trying to capture an environment. Photography is taking a picture of something moving in space and time. But for my doodles, it started with me just dozing off in class. For real! It was because of Zoom, to be honest, I would just be on my iPad and taking notes, but it's impossible to pay attention for that long. The doodles for me are a lot of real time processing. None of them really took more than an hour, even just five, ten, minutes sometimes. They're very fluid, and they're just about, ‘what am I observing right now? What am I feeling in real time?’ In some ways it's a little bit more introspective, as you said, because it's just me with a pen and paper, and nothing on this blank canvas is pointing me in any direction, but I'm hearing things. I have peripheral feelings that are still lingering, and it's like, ‘alright, how do we put it there?’ No one's grabbing the pencil and doing it with me. It really just is me at a desk, or laying on my bed, having fun.

Is that sort of experience very different from your creative process when you're doing something different, whether it's photography, constructing a digital space, working on a VR simulation or a synthesizer?

Generally my work focuses on creating something that involves other people. A lot of my photography involved me picking up a camera and taking a picture of something that I want to capture myself. Recently I've gotten really into portrait photography. The act of taking a picture of someone inherently calls for taking on their perspective, and seeing how they would want to look in this and considering what is the aesthetic that we're both vying for here? With simulations, it's a lot of ‘how might people interact with this environment.’ So it's like there's a level of collaboration that's called for when it's not just me with my one pencil and my iPad that I think drives a lot of, not necessarily a loss of introspection, but rather a sharing of it. With the doodles it really was just a brain fart. Whatever was in my head is falling into pieces.

Would you say that it's a certain element of humanity that gets in the way?

For sure. I’m thinking out loud here, but it reminds me of writing. I spent my entire life writing, especially poems. You have all these thoughts that are lingering, you have all these dreams, and all these feelings, and then you're writing them out, really touching on them. We're constantly thinking, but we can’t always be writing. There’s an element of filtering, thinking ‘what about your thoughts stick?’ What about this can be put into a contract? What do we even do with it once it’s written and done? With artists, like writers, there is this constant dilemma of writer's block. It's just like the feeling of, ‘I'm not at a point where I can share exactly what I'm saying.’ There will be a delay where I'm able to actually finally actualize my thoughts. It's definitely human to think, ‘I can't always be making, but I can be dreaming, and I can eventually make those things that I dream of.’

You keep referencing artists vaguely. Who would you say are your main artistic influences? Poets, musicians– I'm going to accept engineers as well.

Well, one huge influence for me growing up was this Irish musician artist who goes by EDEN. He just opened my eyes in a way that other artists hadn’t, they didn't blend between genres like he did. He was also my first exposure to Asians in mainstream media, and he was an incredible artist because, well, not only is his music awesome, but he's also heavily involved in every stage of his music production. He would often piece together videos out of photography that he had done. That was my first exposure to an artist that touches on everything that I was also touching on, like poetry, music, video. He was definitely a huge influence there. A lot of the influences I had came from growing up with social media - in a good way and a bad way. I was in seventh grade, on Tumblr, and just scrolling, and I would see crazy photography and crazy poetry. I don't necessarily know those usernames anymore, who wrote those pieces, but they stick with me in many ways. Instagram is also constantly just a visual stimulus.

This is like a complete non-sequitur, but I really did want to ask about being a robot for an entire summer. Performance art?

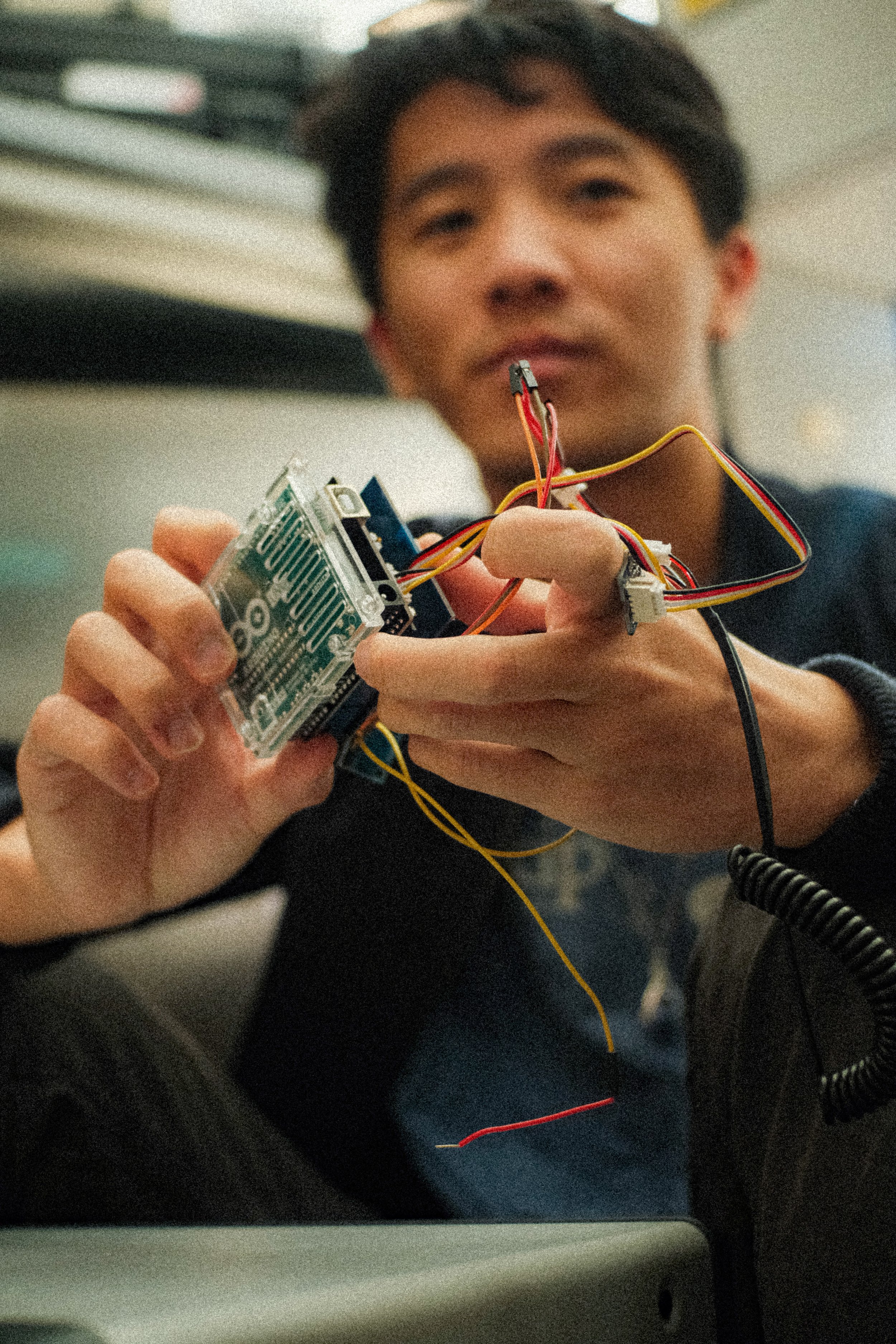

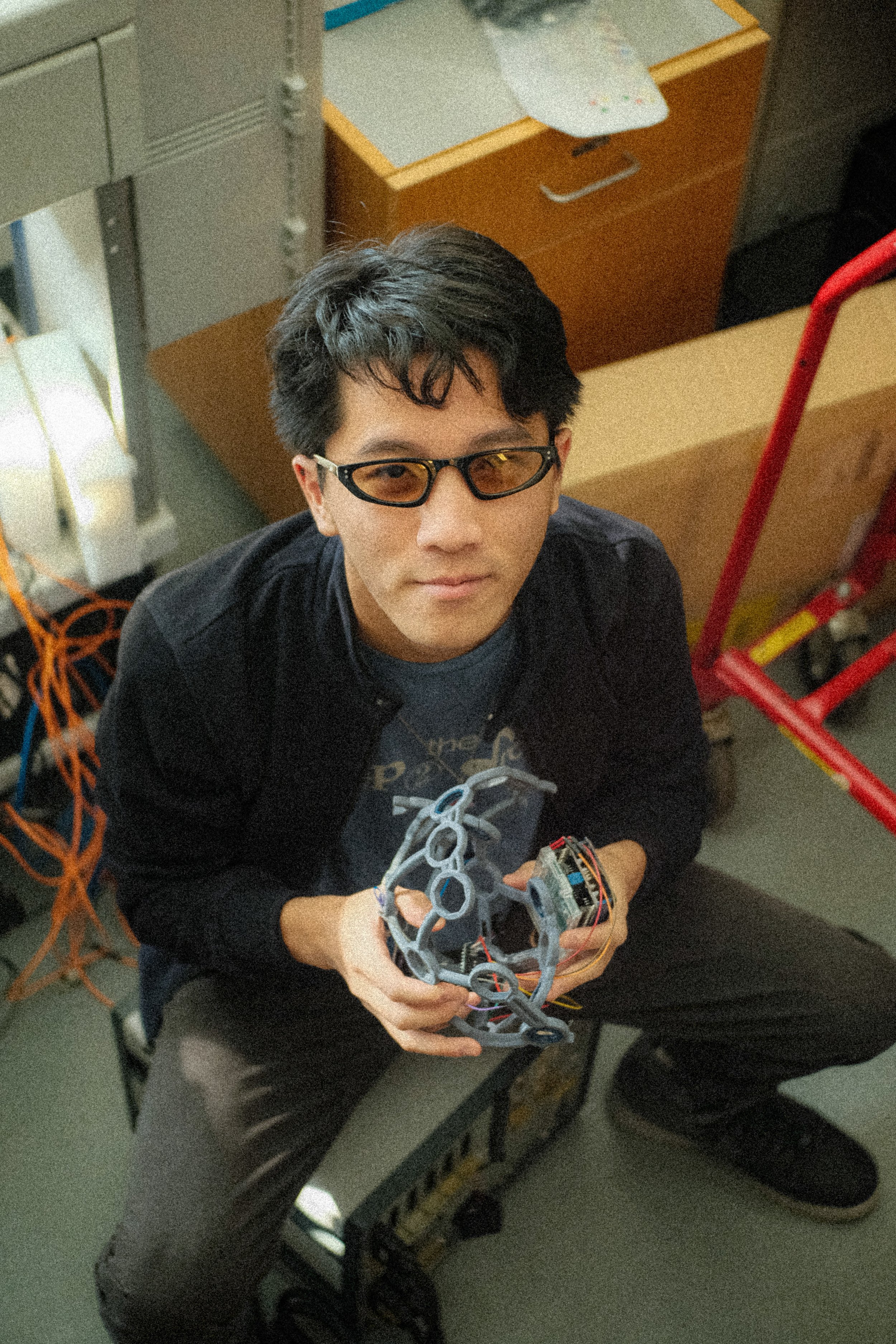

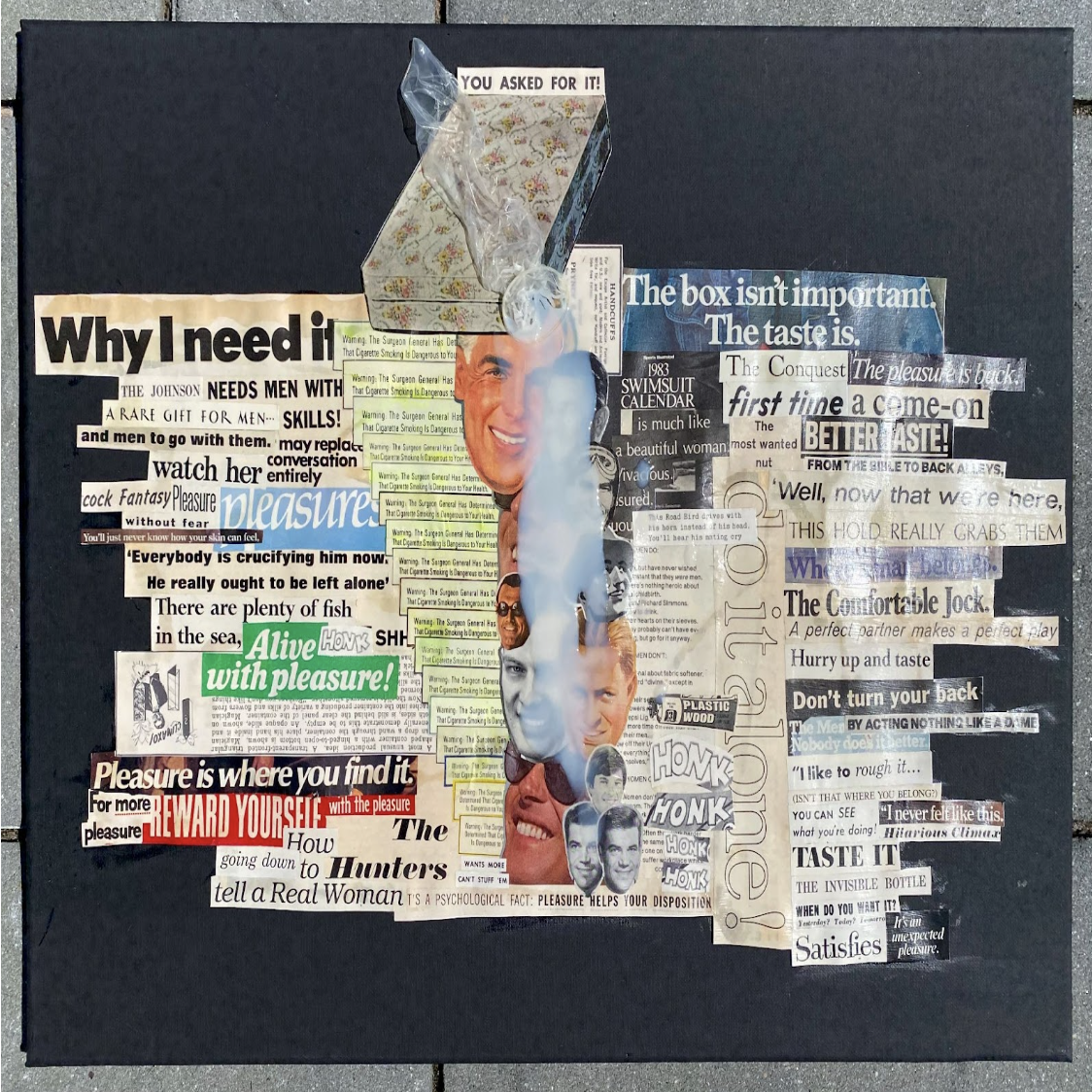

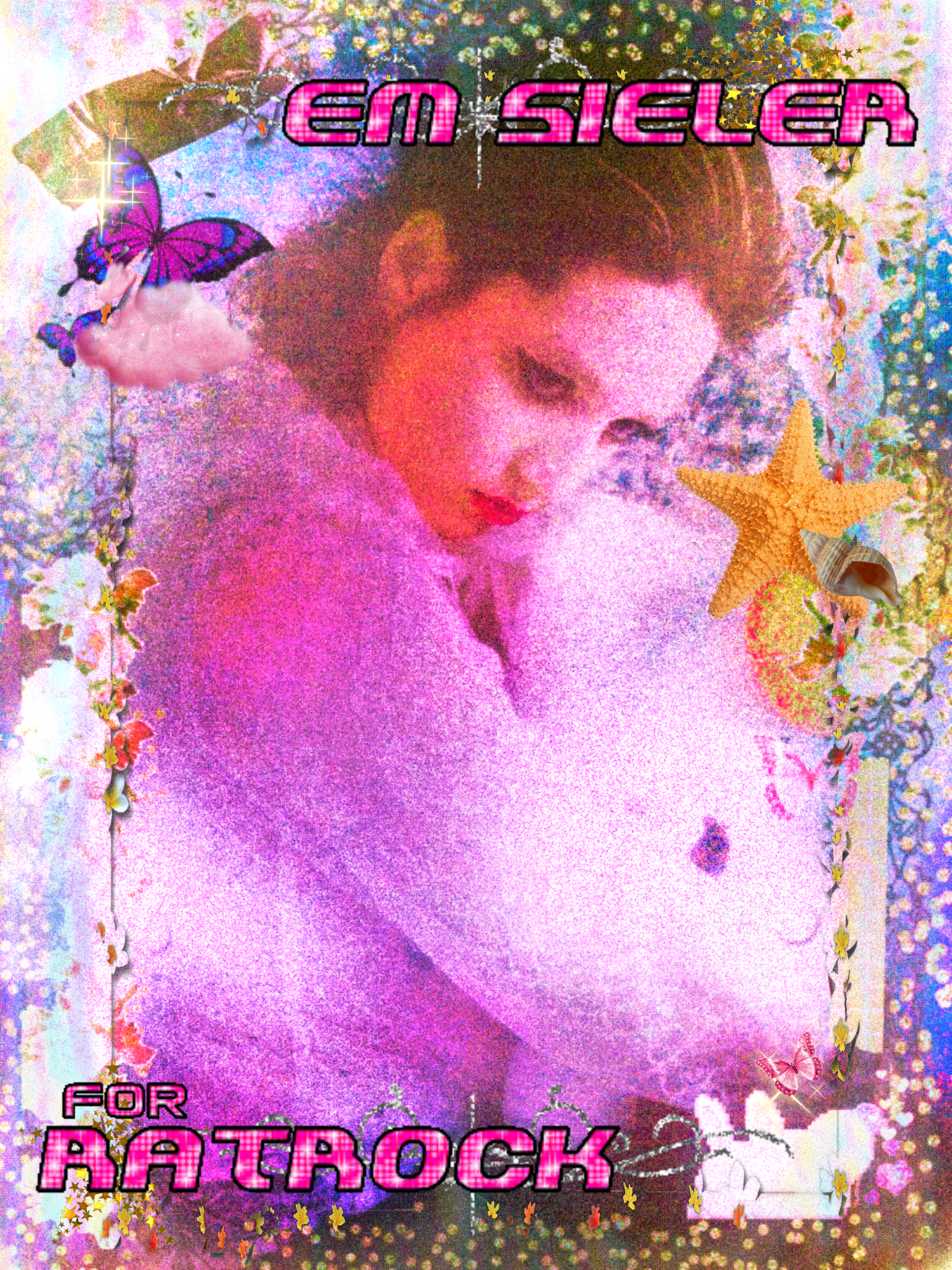

That was actually a part of the VR study. My freshman and sophomore year, we were just building it. We would measure people’s brain signals while they were in the simulation. Eventually my professor was like, ‘oh, we should make this about human-computer interaction,’ as a next step. We were like, ‘how?’ He said, ‘what if we had a GPS?’ He was talking about a self-driving vehicle, because that’s huge right now, so many people are looking into self-driving cars. So I tried programming and self-driving stuff, and it just went over my head. I was like, ‘I don't know if this is possible,’ there wasn't really a framework for that. Funnily enough, because we couldn't make the actual model, the professor was like, ‘okay, what if we faked it?’ There's actually a couple of experiments like this, they're called Wizard of Oz experiments. In the Wizard of Oz, they go through this crazy land, and they realize that someone's behind it all. So for this past summer, I was behind it all. I was pretending to be a GPS, and a self-driving car - like I was literally just sitting in a room while everyone else was in the VR simulator. I was controlling this product for the participants, and talking to them. In ways it definitely was performance art, because I had a vocoder, my voice sounded robotic. That happens a lot in concerts, especially in hyper-pop, a lot of voice translation in real time goes on. I was fully faking being a robot, which was draining in so many ways. I eventually found a balance because controlling this stuff only took one hand, so I kind of split my brain and split the screen on my monitor, and would make collages on the side. I literally would have my computer open because otherwise I would have gone crazy pretending to be a robot for eight hours a day. I was making collages, and also working on a wearable device at the time. I did most of the bulk of my creative work while I was pretending to be a robot, almost out of necessity, because otherwise I was just going to burn out.

Wow. I'm assuming that that has had an effect on your creative work?

Going back to the feeling of grounding, it was kind of grounding to have that monotonous, algorithmic thinking in the background. Meanwhile, my brain is always going to go loose, this happens when I'm studying for exams - it's hard to look at numbers all day. My head just travels. Last summer, I really felt that balance where it was like, ‘this is highly monotonous, robotic work, but it also opens my brain up to being able to tap into some creative process there.’ I wouldn't do it again, but it was definitely an interesting experience seeing how my left brain and right brain interacted. I felt that for the first time, that I have a creative side and I have a logical side that are hand in hand and informing each other, but also not overstepping.

Now, at the end of this wonderful four-year study, at the end of college, looking ahead to grad school, what do you see as the future for your creative practice?

I'm really trying to get into music, and on top of music, visual production. There's so many traditional practices in that field, but all of them could be disrupted by engineering. A lot of manual work that goes into video editing could be streamlined with more efficient technology. There are so many avenues of music production, video editing, and image processing that are possible because of emerging technology. We grew up with pretty shitty– pardon my French– Instagram filters. They look really corny! Nowadays, they can compliment things so well. I spent so long writing and training my eye and also training my ear, but I never was able to just fully make music or fully make music videos. That is the direction I want to go in. I also think that there's room for me to also look into how I can help sculpt future technology, which is admittedly a very wide goal. I don't really have the vision for it at the moment, but I'm still happy to see how it intersects with my engineering and see where things can fall in place.

I wanted to ask this just because you've been talking a lot about it - what are your favorite concerts that you've been to?

One big thing that I got into recently is these sort of garage artists working on modular synthesizers. Which are so analog, they literally look like circuits, and you plug things in, and because you're changing the flow of the current and the energy, the sound is completely different when you do that in real time.There's a huge community in New York, and especially in Brooklyn, where they rent out warehouses and throw these massive events, they’re basically raves. All the people making music have their own little room, but there's no doors, so the sound just travels. On top of the people who are making this music, there's visualizers, so there are people who are also coding in real time. Like I said, EDEN was another huge one. Because in his concerts, he would film things in real time, and then show what he was filming on the projector. There was an element of feedback and he would also record the crowd sometimes and then put it into a song in the future. I always thought that was a really giving way of interacting with an audience. There was another named Elohim, and she was huge on electronic music but also psychedelic visualizers. Her concerts were the first ones that I went to and was like, ‘whoa. I can feel what I'm hearing.’ A lot of this interfacing between music and images has actually kind of given me synesthesia, in the sense that I can now associate colors to sounds. That's part of the beauty of having some kind of visual element to music. This is why we have music videos. Even Spotify right now has those little GIFs on repeat while you listen. It definitely adds an element of storytelling to the music.

Is there anything that we haven't spoken about, or that I haven't brought up, that you want to talk about, or say?

I'm still trying to grapple with where art falls into narratives. Most recently, over the summer, I built this little wearable device that helped senior citizens track their mood and interact with what was basically a Tamagotchi. It would also share their recordings of what they're feeling with their families. There is space for creating technology that enhances or allows narrative. If there's one more thing I could say is that I didn't really include writing in my portfolio, because I wanted to kind of keep it audio/visual, but in the past, writing was definitely my first step into art. The feeling of reading and having storytelling embedded in me was how I even got my muscles to share. Growing up, a lot of what inspired me to even pursue art was the fact that I've written so many poems, and short stories that I wanted to become movies or songs and had to find a way to integrate them into something. Like I was saying, Spotify now has lyrics and the storytelling process, they're all just dimensions adding on one another, and they all go hand in hand. That's like a lot of what I've tried and will continue trying to explore.