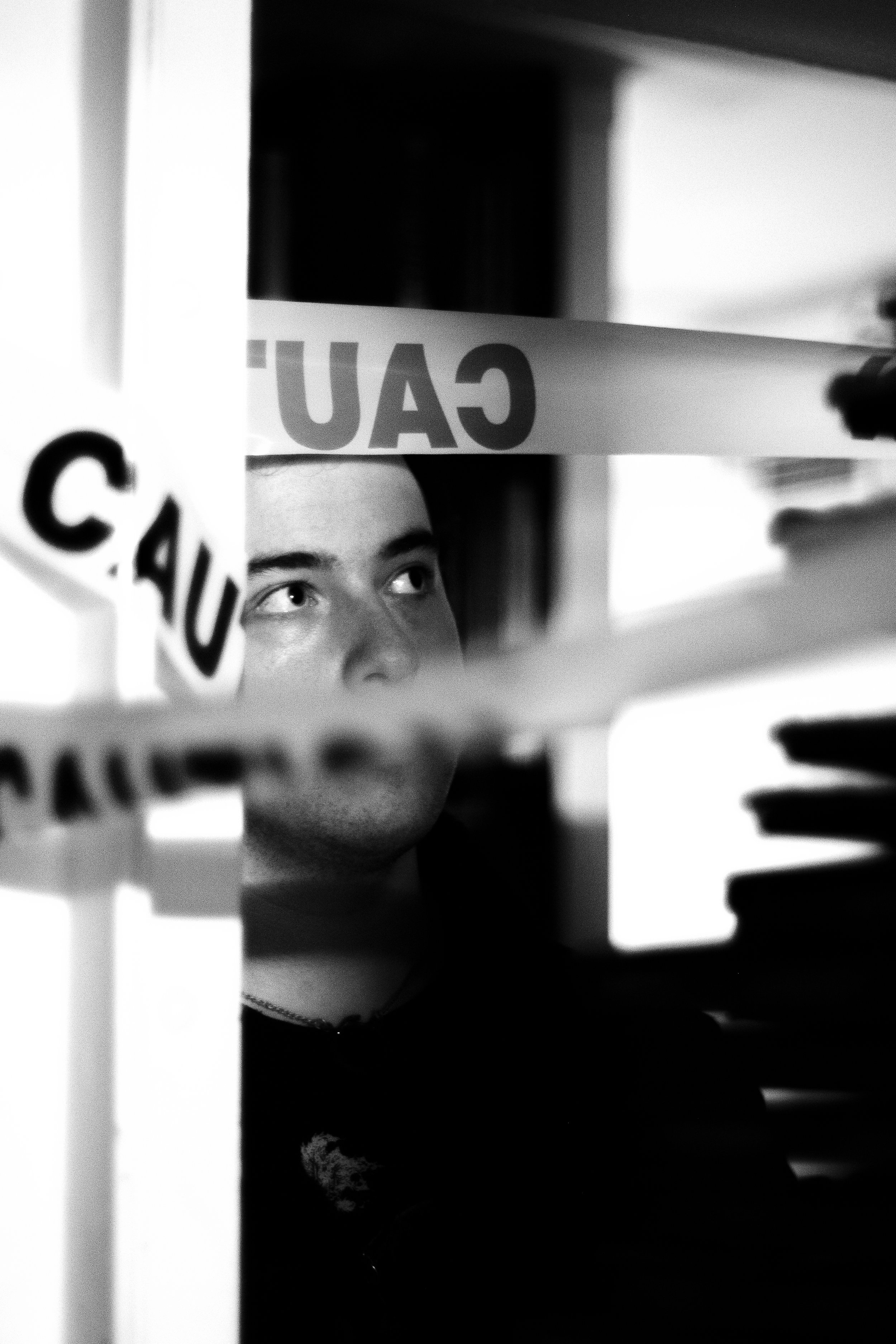

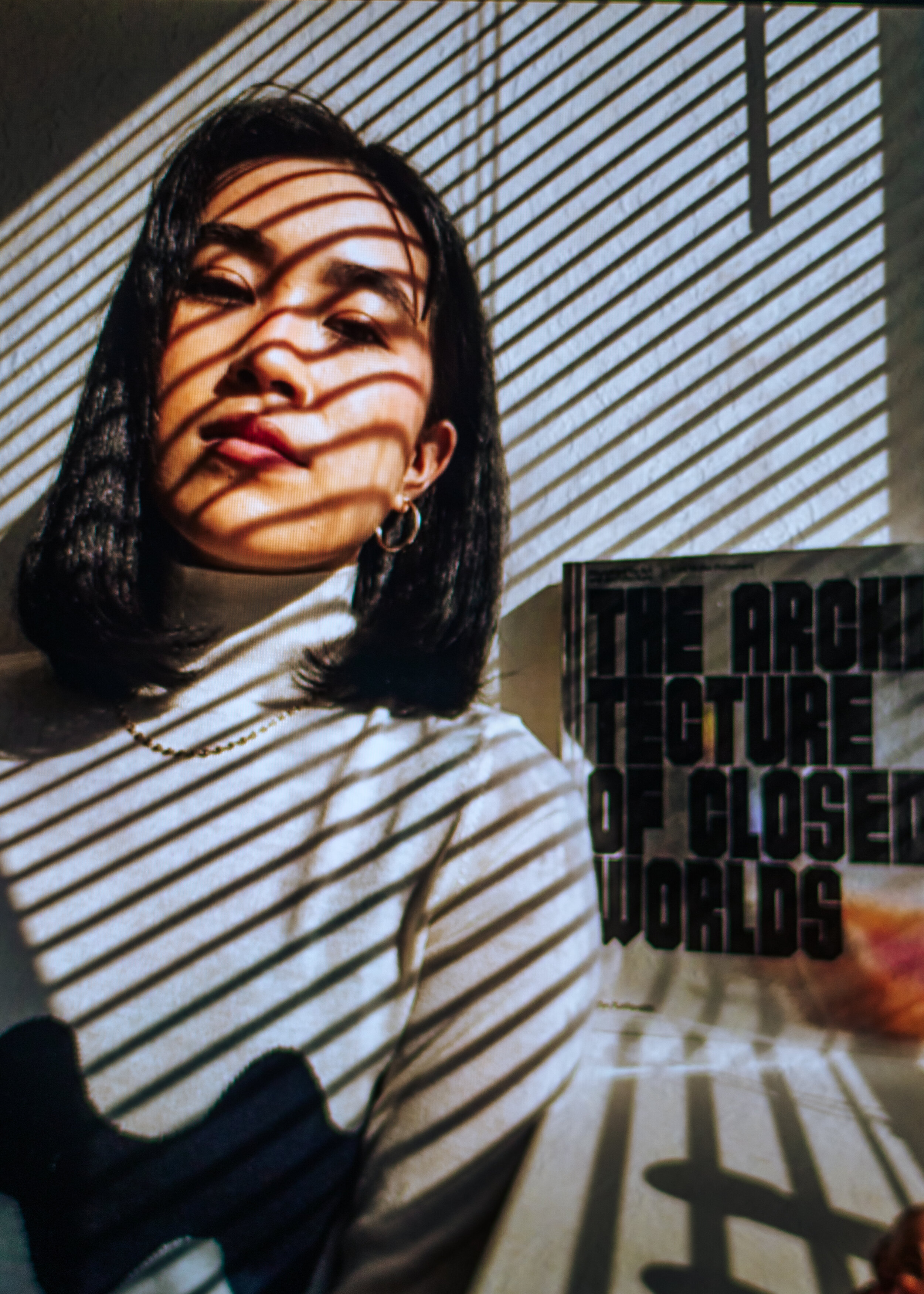

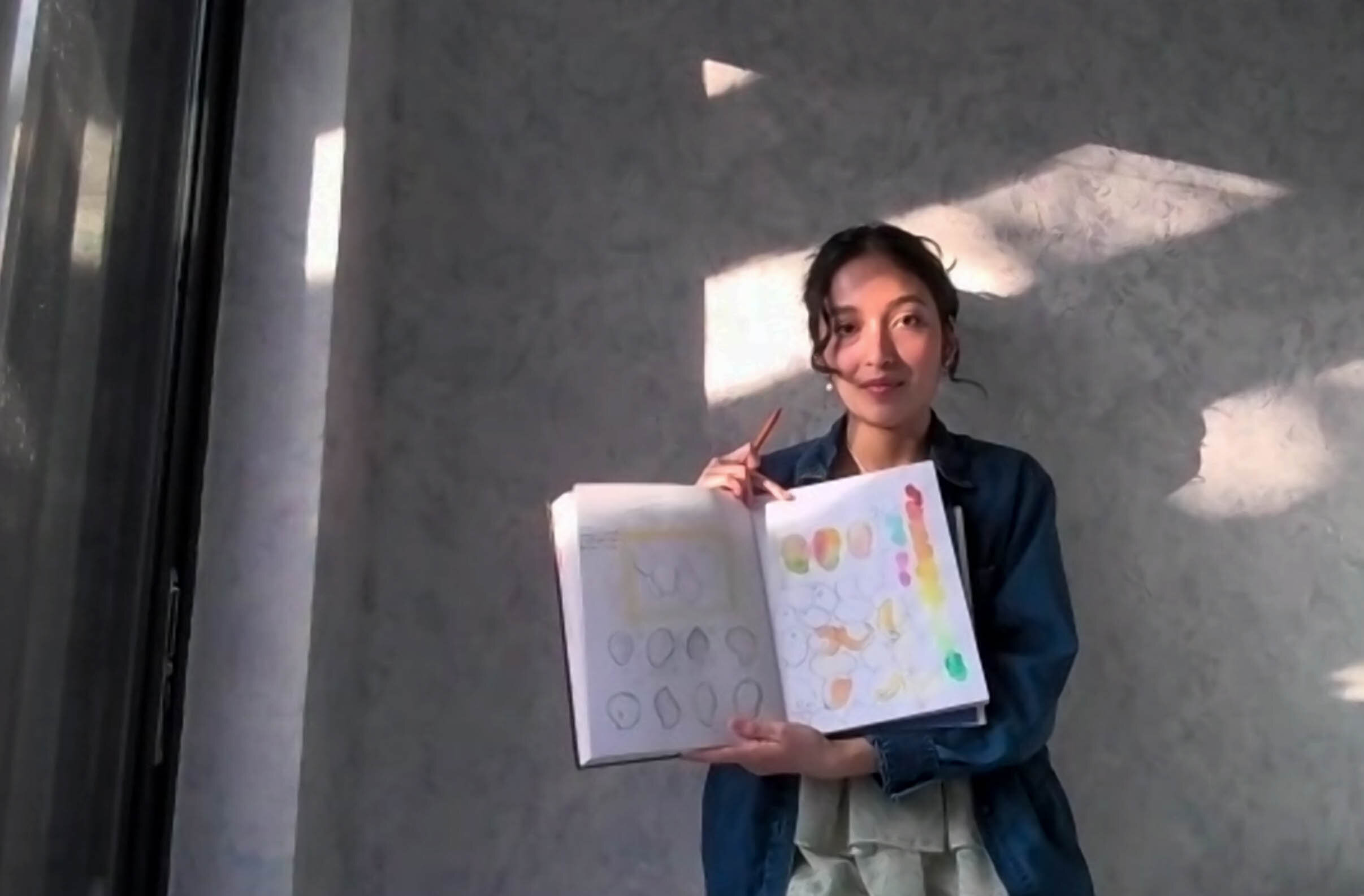

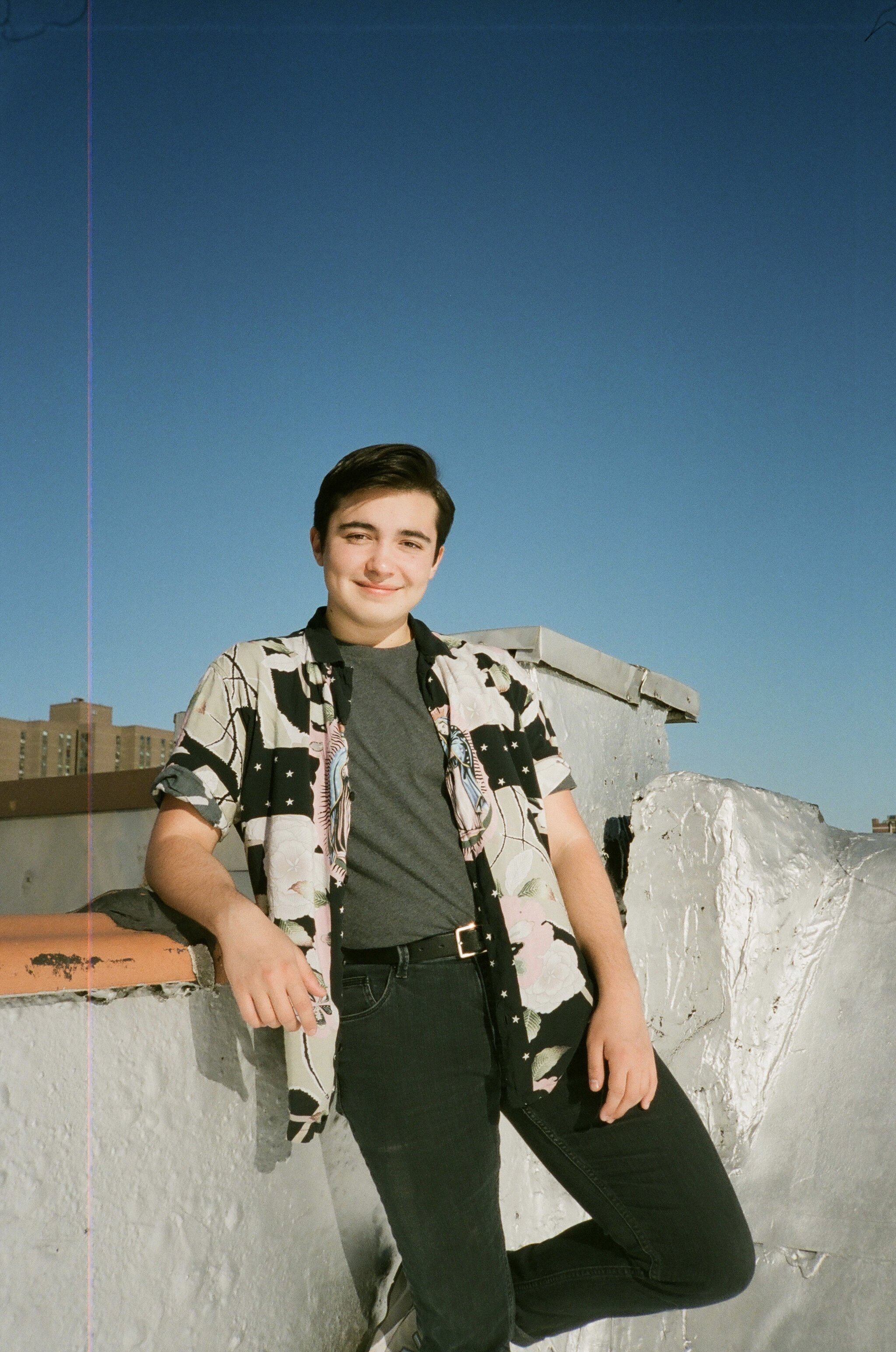

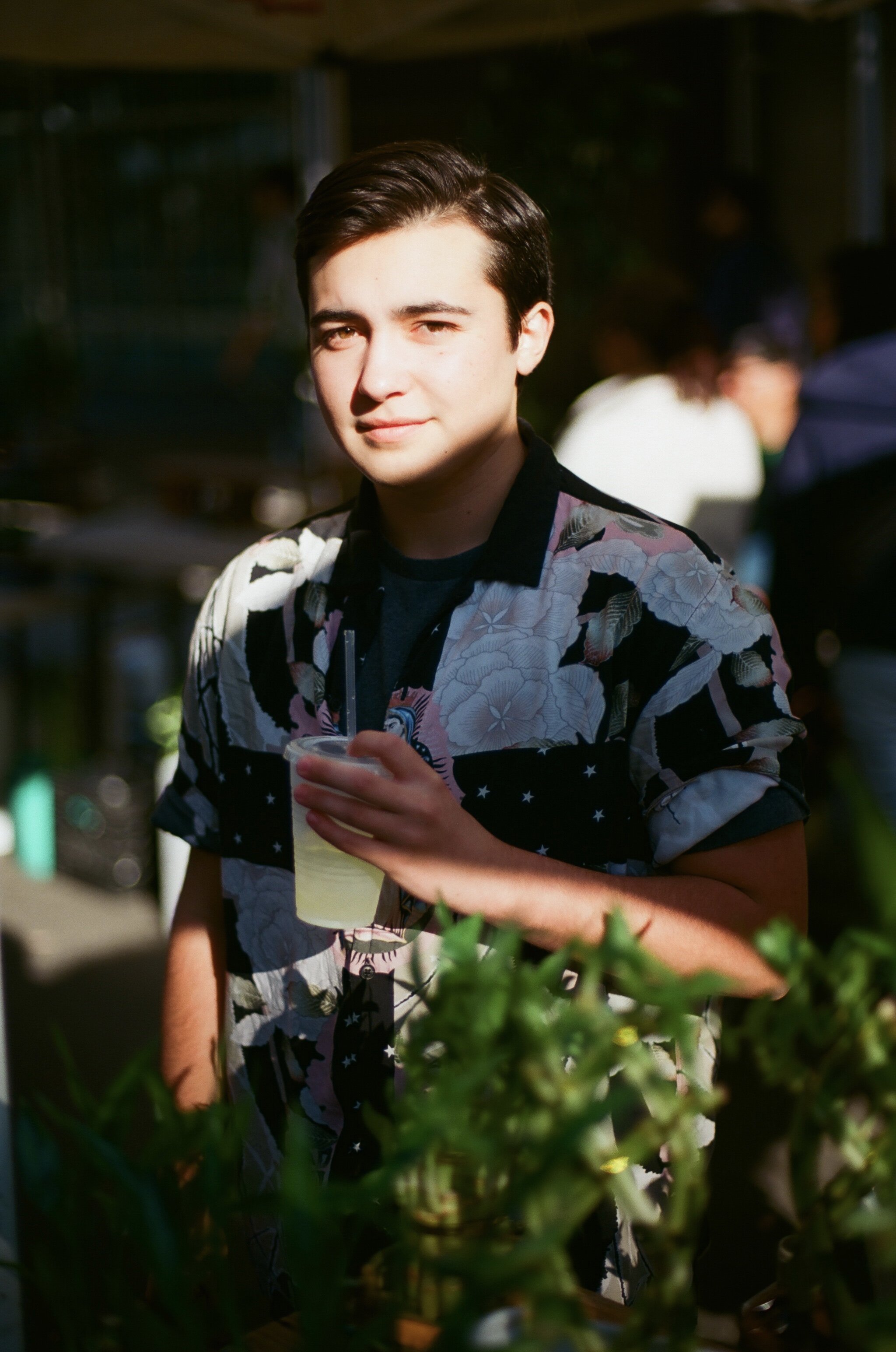

Interview by Isabella Rafky

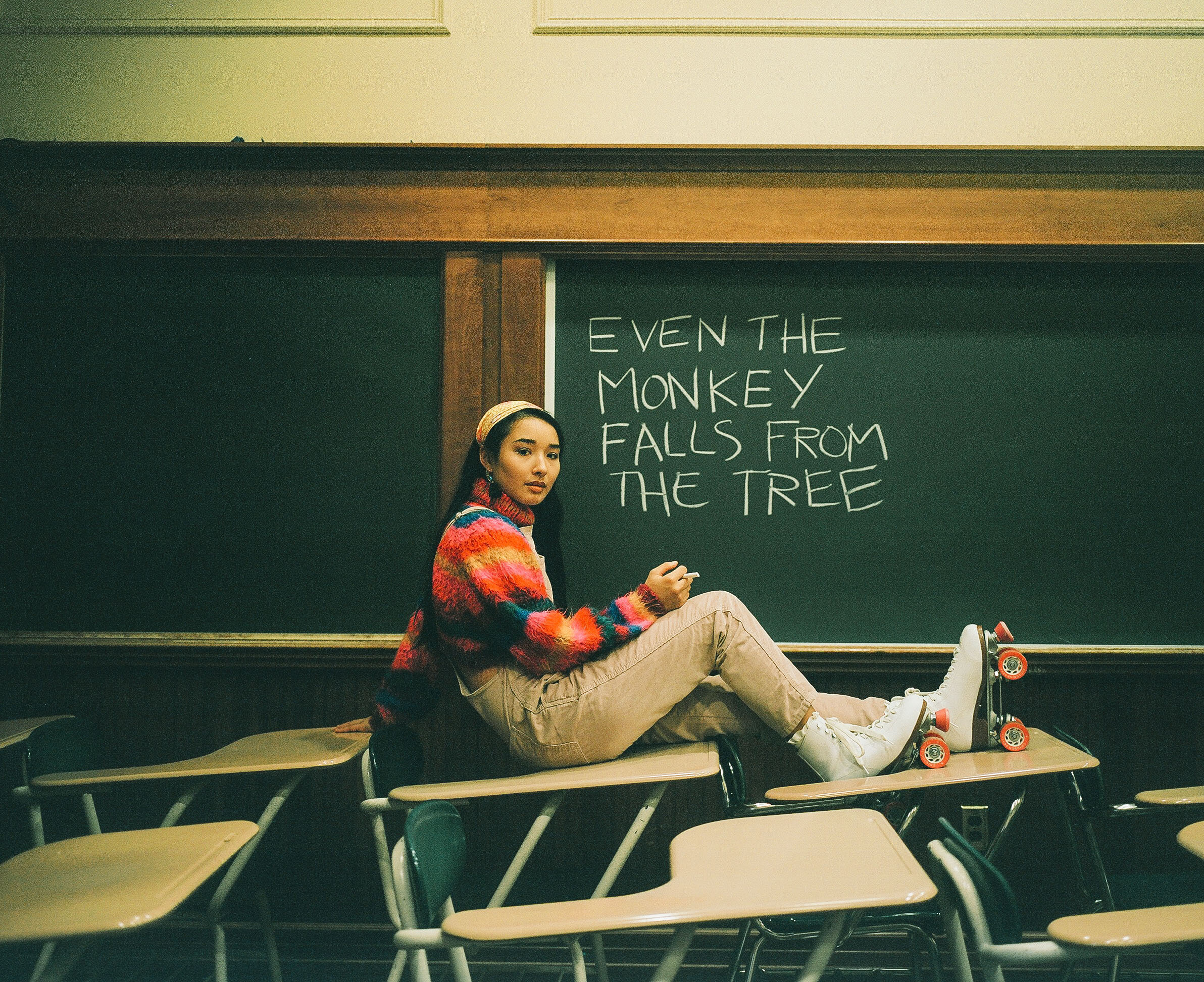

Photos by Rommel Nunez

Can you tell me a little bit about yourself?

Okay. I am 22 years old. I am originally from St. Louis, Missouri. Kind of random, but it’s a fun place to be and I feel that I’ve gotten to appreciate it more and more the longer I’ve spent away from home. I’m an only child, which is kinda good and bad; I wish I had a sibling, but at the same time I love my parents. I studied architecture, I’m a senior, but I also do a bunch of random design projects in my personal time. Oh! and I’m a dancer. I feel like I’ve kind of neglected that because of the pandemic. But yeah, I’m also a dancer.

When did you know you wanted to practice architecture?

My first exposure to it was when I was in 6th grade. So I was like, 12 years old or something. I feel like that’s kind of the natural path for kids who like both math and art, and I was a really big math and art kid. So, one of my teachers recommended that I look into architecture, but as a 12 year old there’s really not much you can do at that time. But then, the summer after my sophomore year of high school, I did this architecture camp at Washington University in St. Louis. This was while I was in high school, I was going into my senior year and it was like a sustainability and architecture high school program. It was so stressful, but I ended up loving it. Like that type of weird stress that’s like drawing lines constantly until like 2 in the morning. So I figured that I liked that after doing that little summer camp. And then yeah, in 2016 I did a program for high school kids also. It was really my only career choice, I’ve always kinda known that I wanted to go into architecture.

So, what inspires you in your work currently?

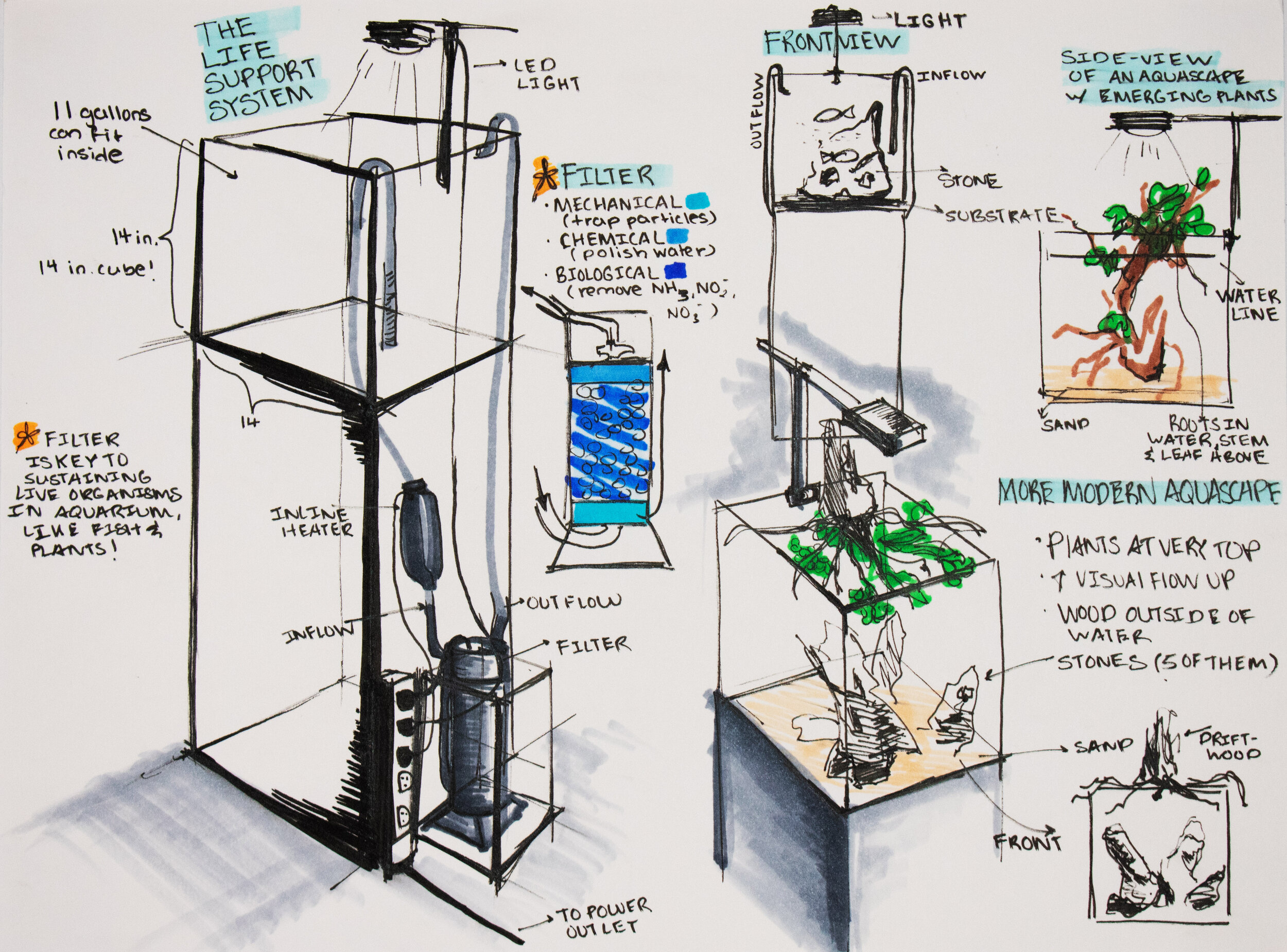

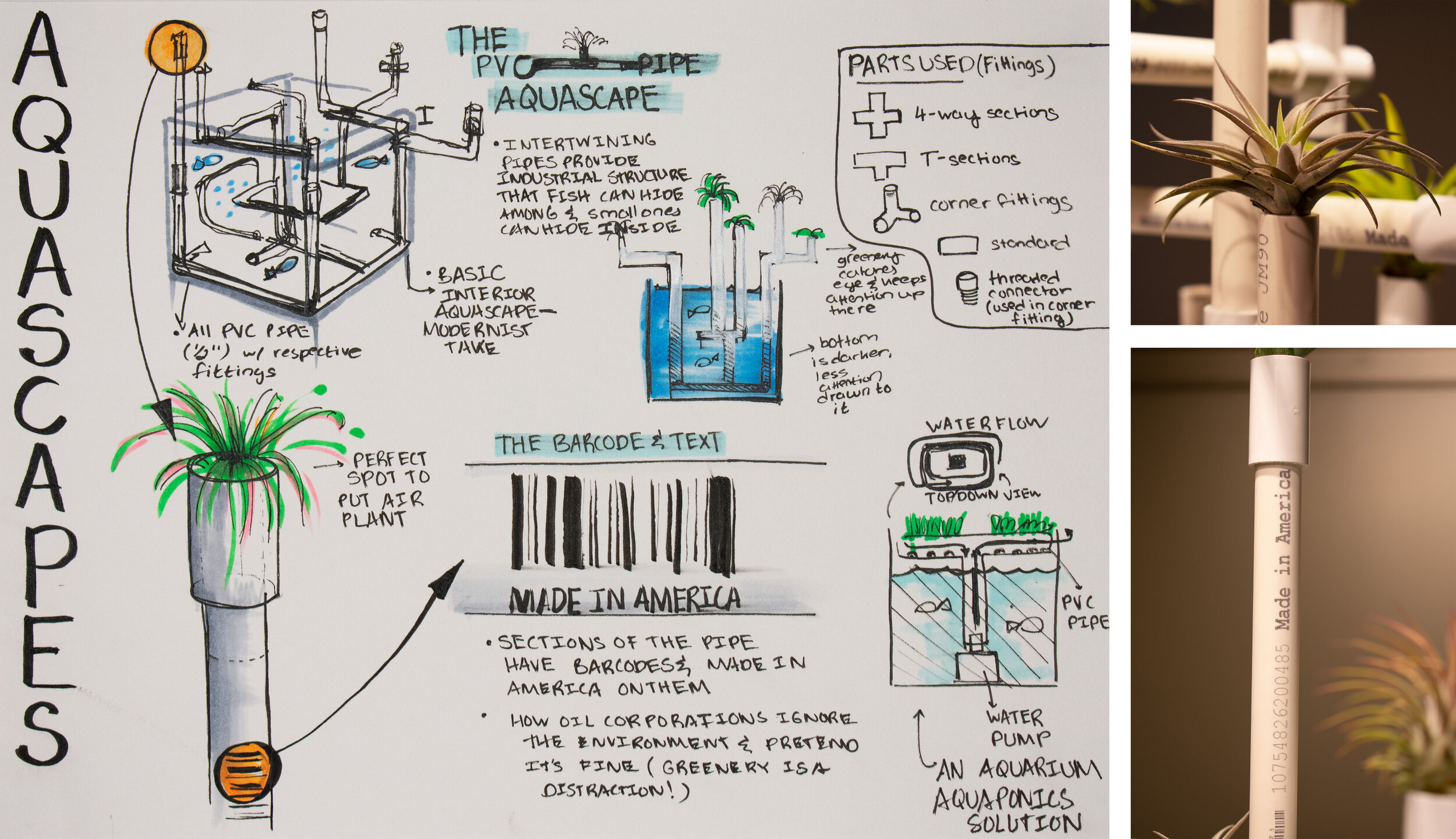

I feel like recently I've been getting... I don’t want to say further away from traditional architecture, but I have been interested more in furniture and objects recently. I think it’s because I’m dealing with the struggle of whether I want to create or help create more skyscrapers or other things that are not so environmentally friendly. It’s a little bit better if I narrow down and create smaller architectures, something that’s more personal and intimate rather than something that’s large and urban.

Furniture is something that allows me to use those skills that I’ve gotten from architecture to create something a lot more personal. Also, they are a lot easier to produce, a lot quicker to produce, rather than getting into a huge project team and creating a whole building. The process is a lot more personal and a lot more prolific and exciting to me. There are a lot more possibilities.

What sparked your dynamic love affair with furniture?

I’ve mostly covered it, but the main thing is that I have a more personal connection. I see a lot of architects creating furniture that are part of their line or brand, and that's really cool because the furniture kind of becomes a symbol for their architecture as a whole, becomes a more accessible form of the architecture. It’s very consistent with their design language, but yeah, it’s on a one-to-one scale rather than a large community or global scale which I find really fascinating.

I saw your lamps by the way, beautiful! Do you make them from the bottom up or how do you design them? I want one in my home!

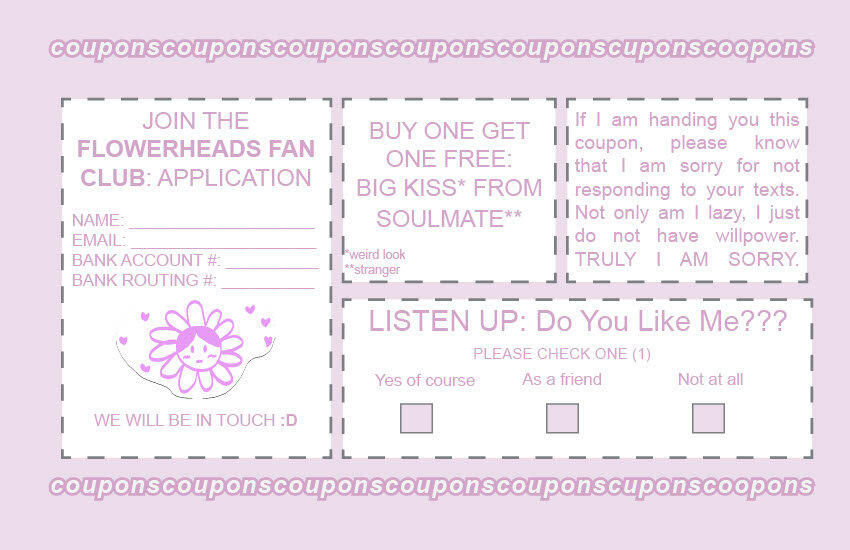

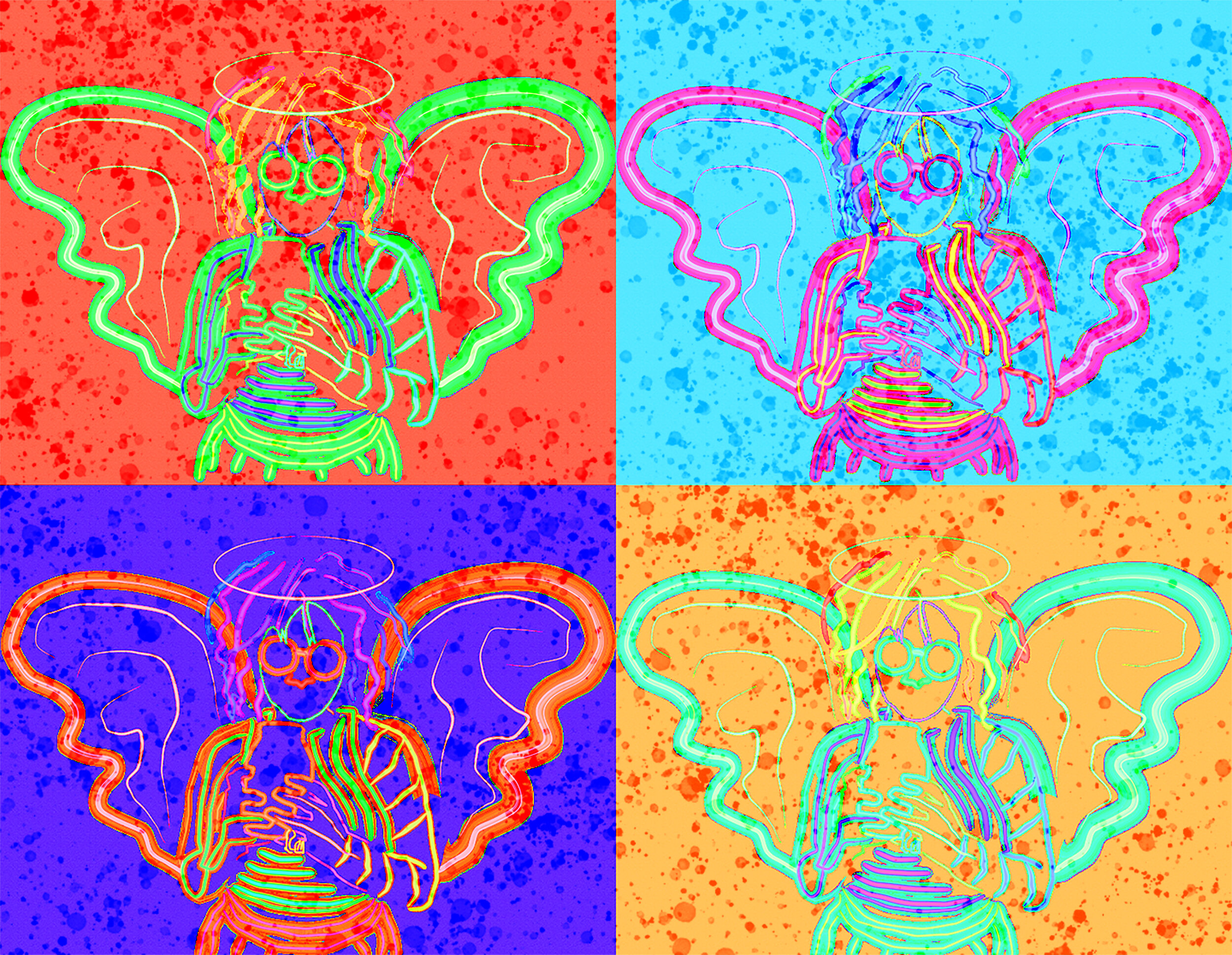

Thanks, the ultimate goal is to get them manufactured but that’s gonna take a lot of time. So that was a project for Design Milk, they collaborated with this annual competition called LAMP. It’s an annual competition, open to students and professionals, and they call people to design lamps and they can be anything. My friend who I met when we studied abroad in Copenhagen, her name is Krista [Lebovitz], we collaborated. She’s a studio art major, I’m an architecture major, so neither one of us has experience in industrial design so it was quite a challenge for us. But it was really fun, we wanted to create something that was very approachable and accessible to the general public because some of those lamps get very avant-garde, very sculptural, just not accessible.

The lamp kind of symbolizes my desires and my goals in design, to create something interesting and exciting but not so completely unattainable to a general crowd. As you said, you can just put it in your room, in your house, on your desk, whenever, and it’s not something that is a giant investment. So far it’s just a rendering, but hopefully, we can figure that out. We actually ended up winning the student popular vote section which is really fun! Thanks for the votes from all my friends.

How long does that process take you? How long did it take to do that lamp project?

So, Krista reached out to me when I was in quarantine, starting the fall semester and I was so bored. She was like, hey, do you wanna do this project with me? That was the first week of September and the project went until late October, early November. So it was just a few months and we met about every week. As I said, the timeline for these projects is a lot shorter, which is why I think they’re more fulfilling, more exciting.

Do you think you’re going to keep going in the furniture and object direction? In industrial object types rather than buildings or different things of that nature?

Yeah, that’s been something I’m thinking about a lot, especially because I’m going to apply to graduate school next year and I’m applying for jobs in the city now so I have to figure out what field I want to go into. Right now it’ll be a bit better for me to go into architecture, and I still love architecture, but I think it'll be a lot easier for me to narrow down my interests later on. Start with architecture and later if I want to go into furniture, then I can more easily. If I were to go to school for furniture design or object design it would be a lot more difficult for me to go into architecture after that. Because architecture is a much wider field, has a lot more technical skills, and I would be able to translate those skills easily into more specific fields rather than going the opposite direction.

What do you find yourself gravitated towards when you’re in the process of building something? And this can mean music, this can mean art, different references that you have, it can mean whatever it wants to mean to you.

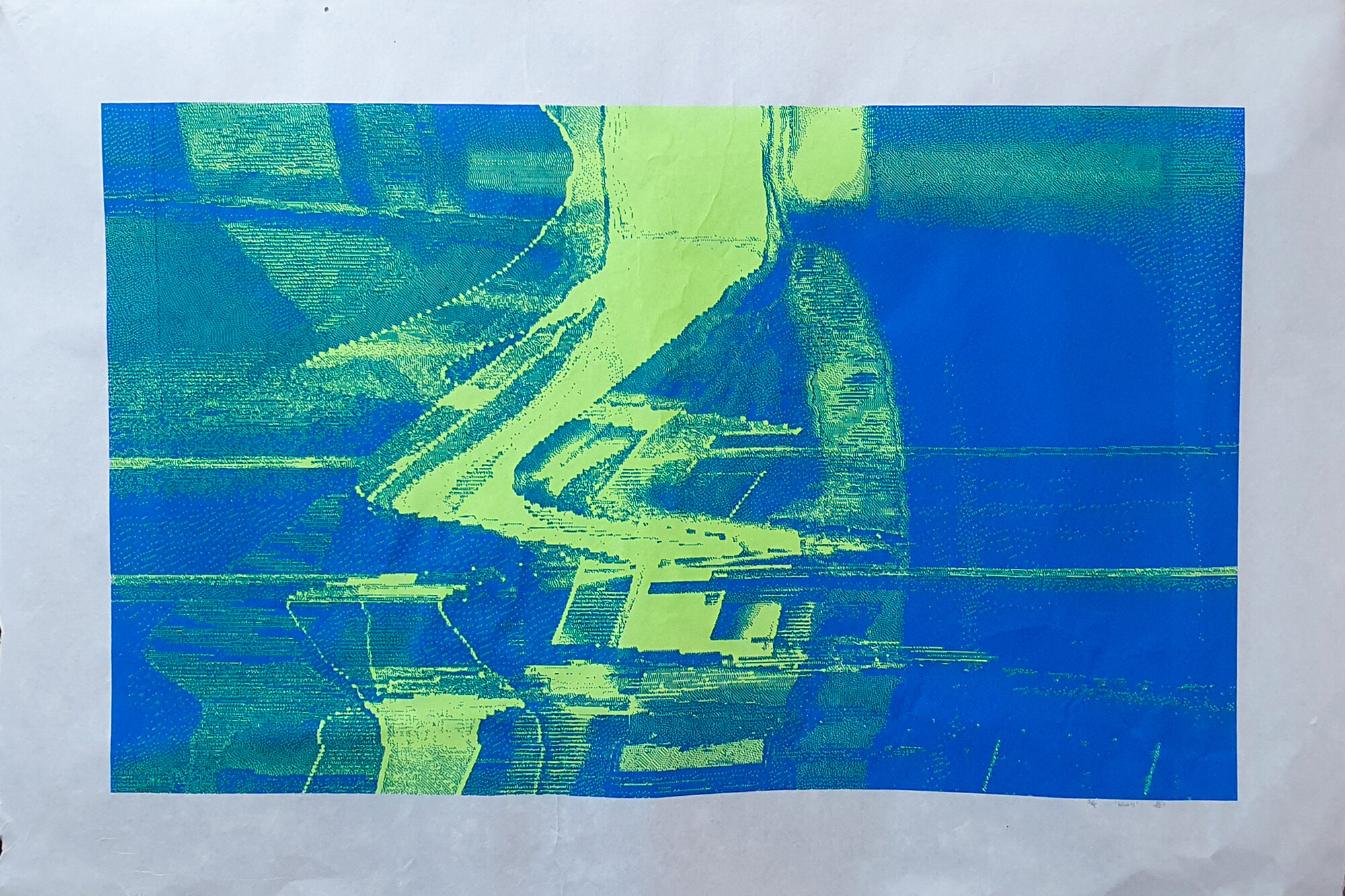

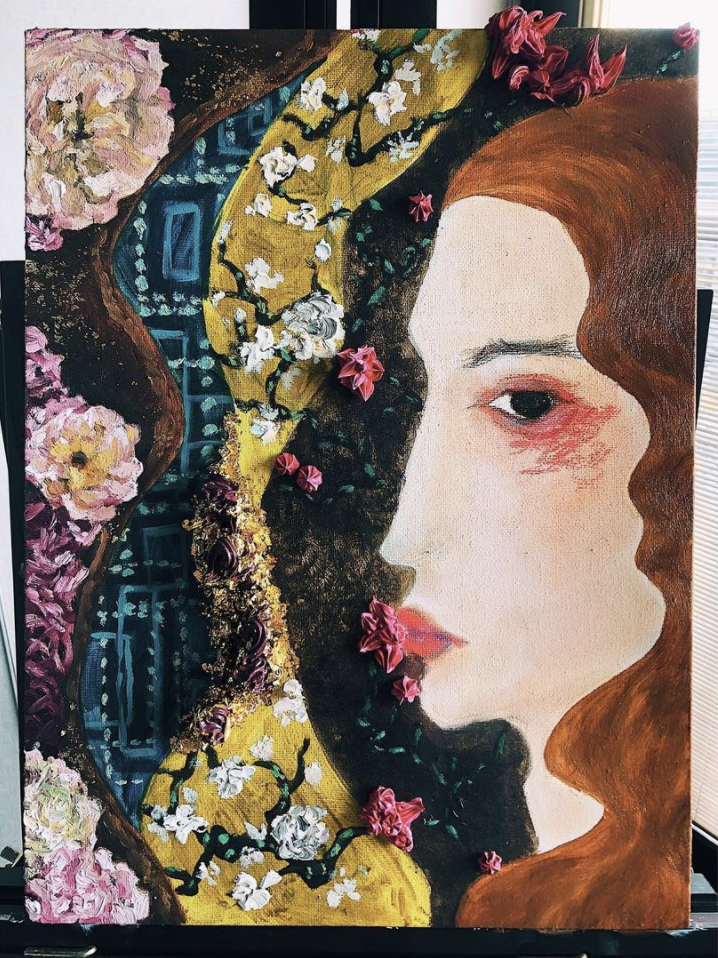

Like I mentioned, making objects is a lot more personal than creating these huge architectural projects. There’s a lot less of an environmental impact, a lot less of social and political connotation that architecture might have. I really want to make objects that are inclusive to all people and that are exciting for all different types of people. I also am very interested in fun colors as well, as you could probably tell from my lamps. I also want to start doing more with different textures and materials. My goal this year is to start knitting. But yeah, I definitely want to be making furniture as well as architecture and my ultimate goal is to have a small design firm where I can do both. I create a space as well as the objects inside of them. Very inclusive, very fun, nothing big or elite.

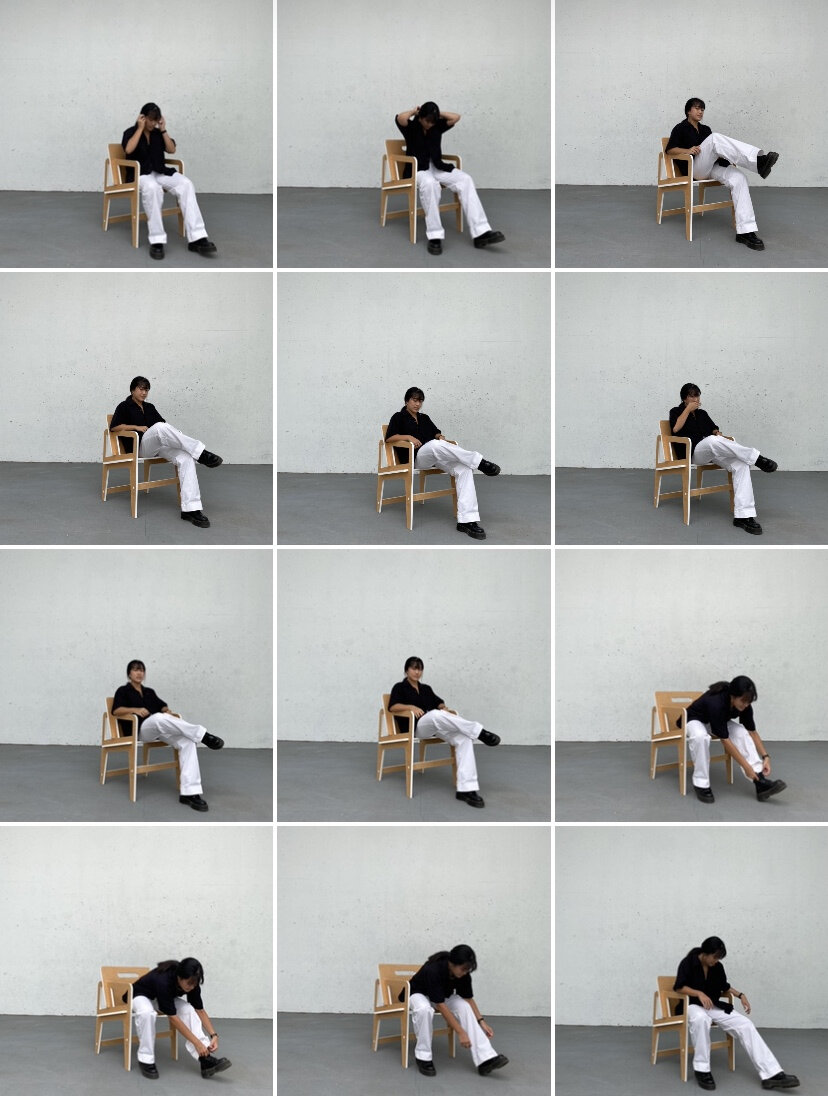

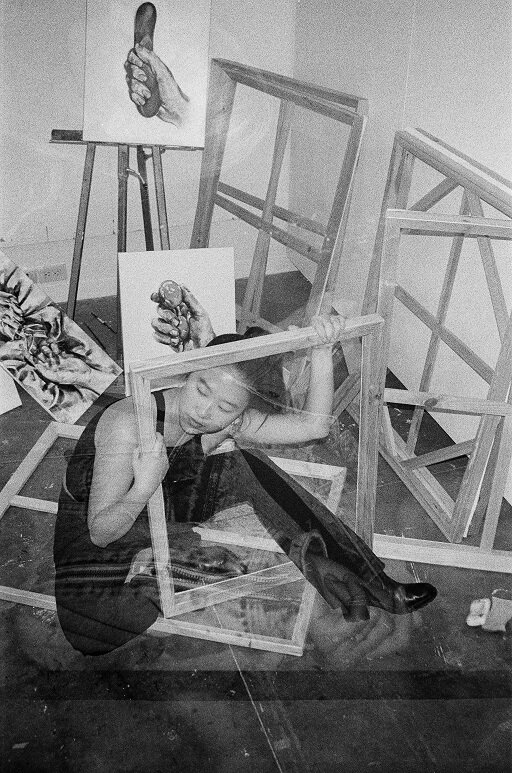

What is your artistic process like? How do you get from point A to point B when creating something like your chairs? Is it something that’s assigned to you or how does that come about?

Generally for all of my projects, like many others, they just start with a sketch. I’m not very strong with sketching though, so I just try to make study models out of paper. My sketches start to translate into little models like that. And then, I usually go into Rhino or other software and start modeling them digitally. From there, it just depends on what medium the project is going to take. For the chair project, I was actually assigned in Denmark when I was there from January to March in 2020. That was a class project where we were making chairs and I went through a series of study models, both small as well as one-to-one scale out of cardboard.

That program actually got canceled because of the coronavirus so then I had to go home. I was really sad that I wasn’t able to finish it. So I just went and luckily had all the 3D files that I was using to experiment with form, and I just took them to a studio where they cut them out from a machine and I was able to build it there. That was actually my first project where it was made to full completion. Because my other architecture projects are buildings, they’re not actually going to be made right now. So I thought that was very fulfilling, actually getting to see my sketches totally coming to life. Now the chair is in my basement and I can sit in it and do my homework while sitting in it. So yeah, it’s different for every project but that’s generally how it goes.

How have you and your work changed through the pandemic, if it’s changed at all?

I definitely was more into traditional architecture prior to the pandemic. It’s also interesting because I was in Denmark right before it all started, which kind of started that shift, and then the pandemic completed the shift. I was definitely more into architecture prior to the start of the pandemic and then I’ve kind of not been dancing as much as well. So I’ve been focusing a lot more on my design and more on art. Before I felt like dance and architecture were kind of splitting my time and I wasn’t able to get fully immersed in either one. I definitely feel a lot more connected to my work, I’m a lot more excited about my work, and I’m able to use my free time because now we have infinite free time [laughs]. So I’m able to use all of that and produce more work. Before I never felt that I was making work during my free time, it was always for school. Now I have projects that I’m proud of that I can say like, I’ve created this opportunity for myself, or I’ve found this independent from school, so that’s been really exciting.

That’s super cool. Do you feel that your practices intersect? You were saying just now that dancing and architecture were different worlds pre-pandemic, could you elaborate on that a little more?

Both of them are very closely related to space and the body. Working with furniture has definitely helped me understand the body even more, in a different way, with different proportions. I would like to do a project in the future where I make a chair and I have a video where I dance with it or something. But right now, it makes me really sad that I put dance on hold because now that I’ve gotten so immersed in design I definitely feel like there’s even more of an opportunity for me to integrate those two. Right now, I don't have any projects right now where they integrate each other. I actually did one project with my friend Melody in 2019 where we choreographed a piece that was kind of inspired by some of the work that I did. That was really fun, but I definitely want to do something on my own that’s like my choreography and my art shown in it. So stay tuned, maybe that’ll come soon.

How do you practice architecture in your personal life, outside of academic projects and the classroom?

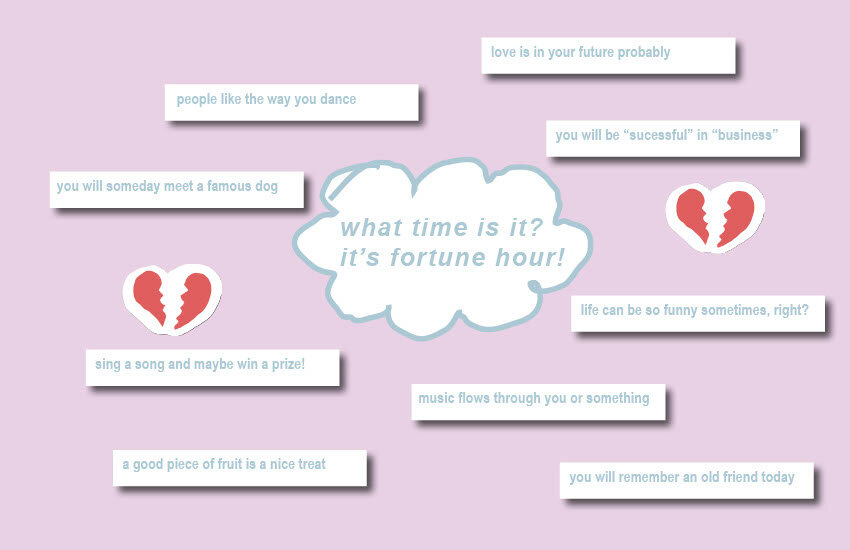

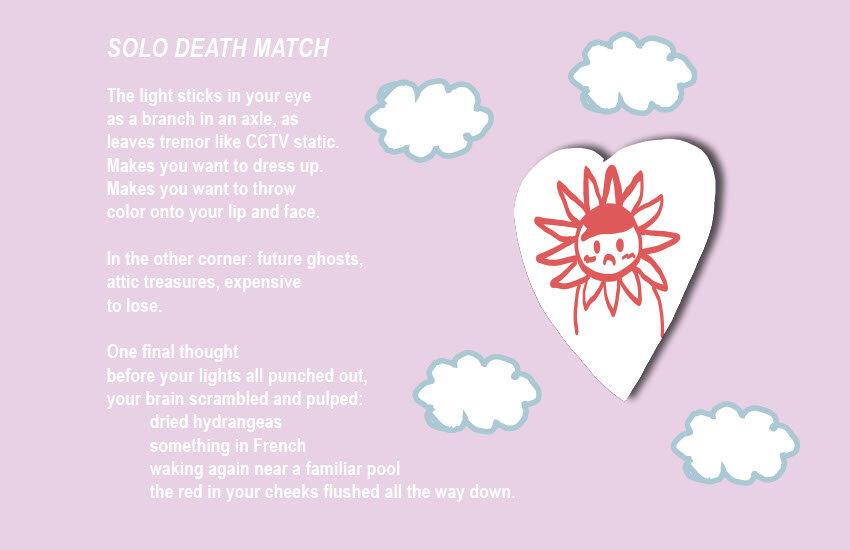

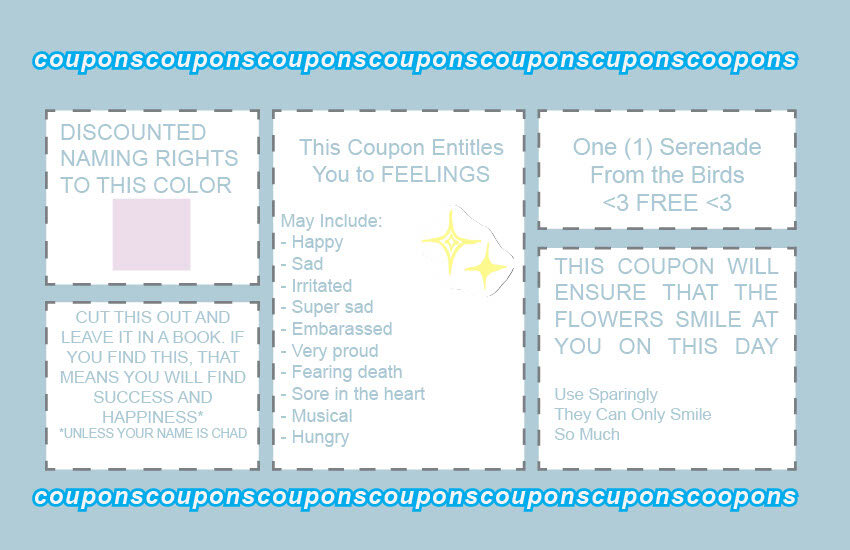

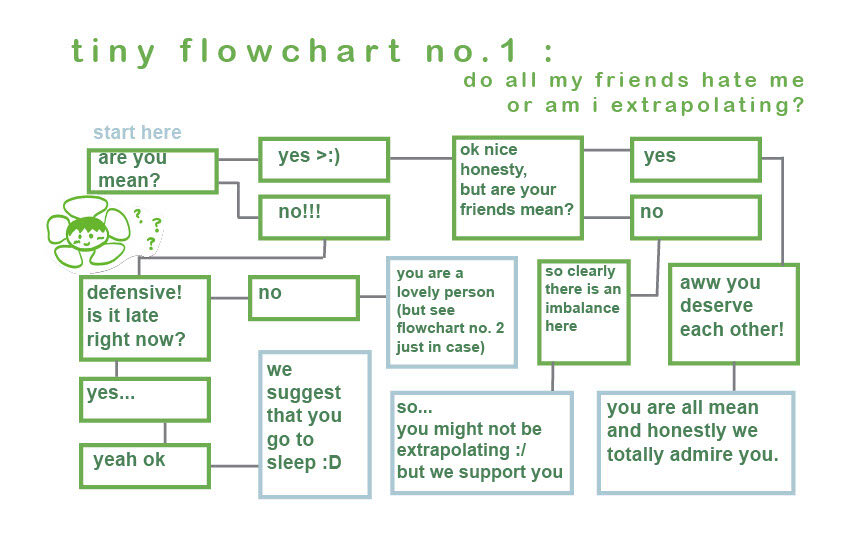

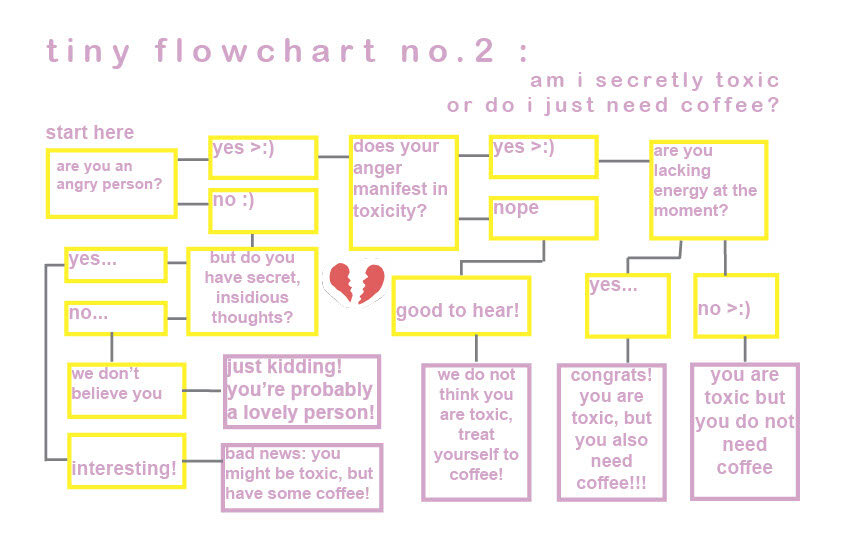

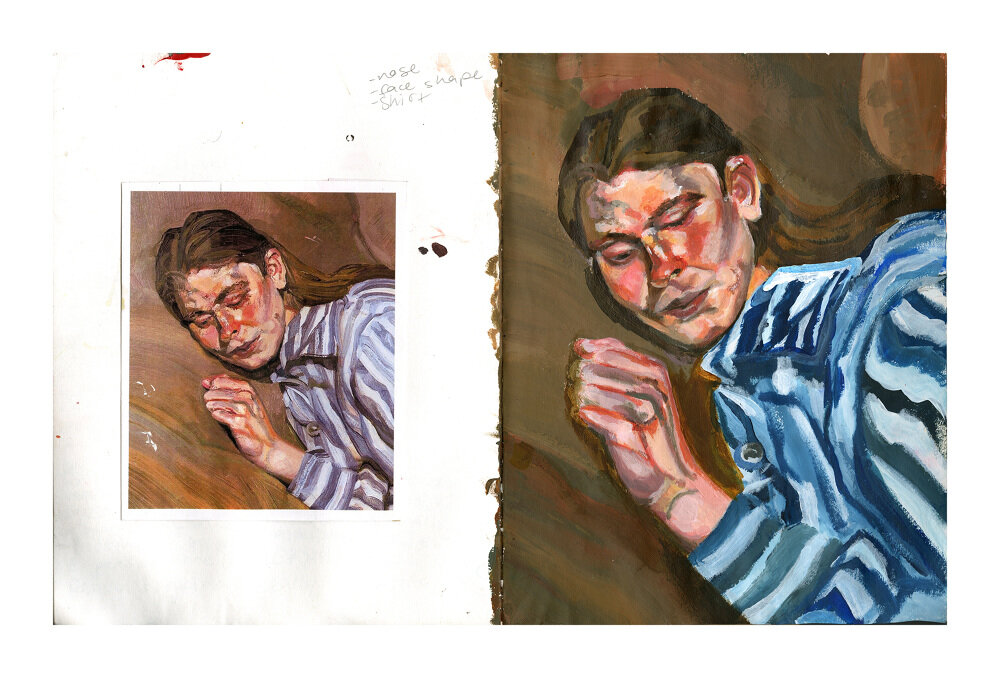

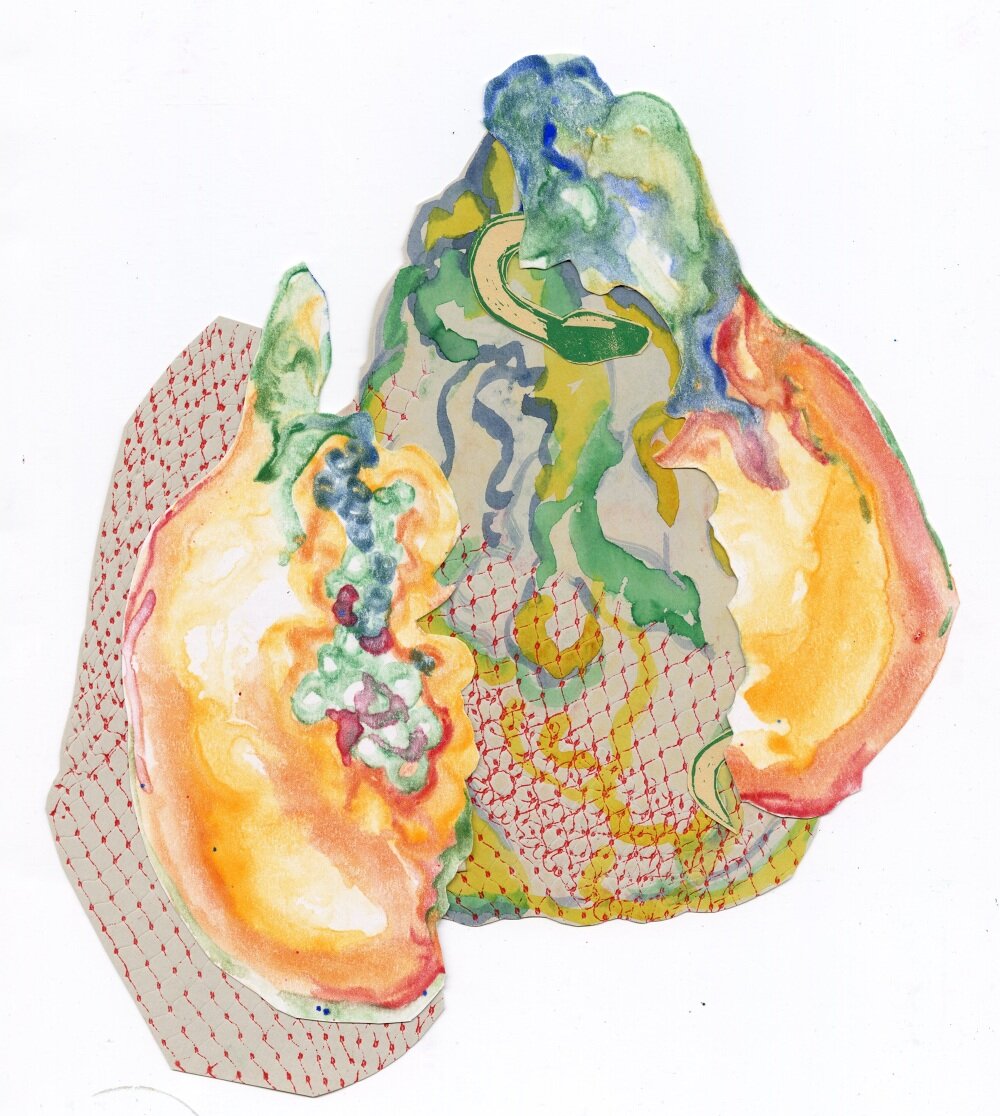

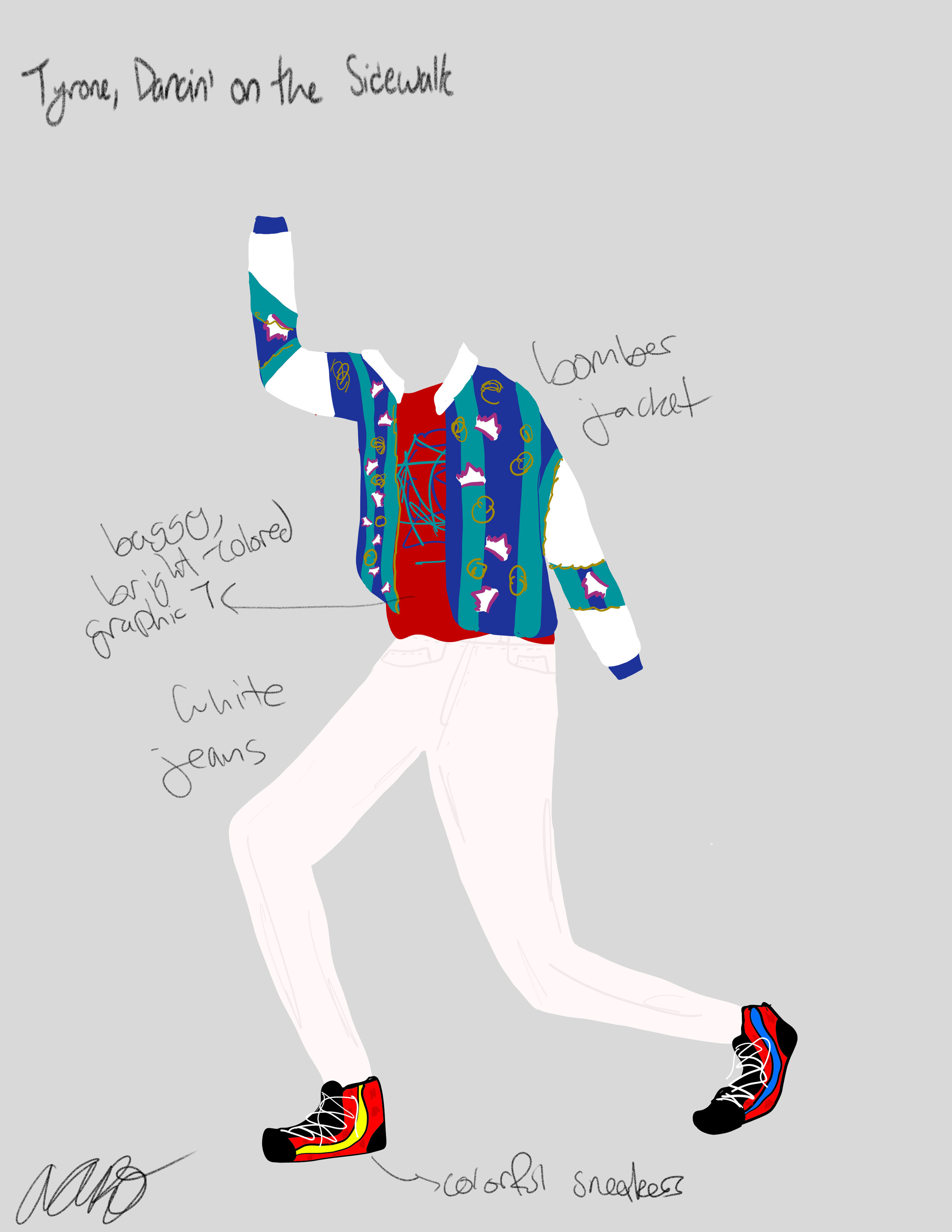

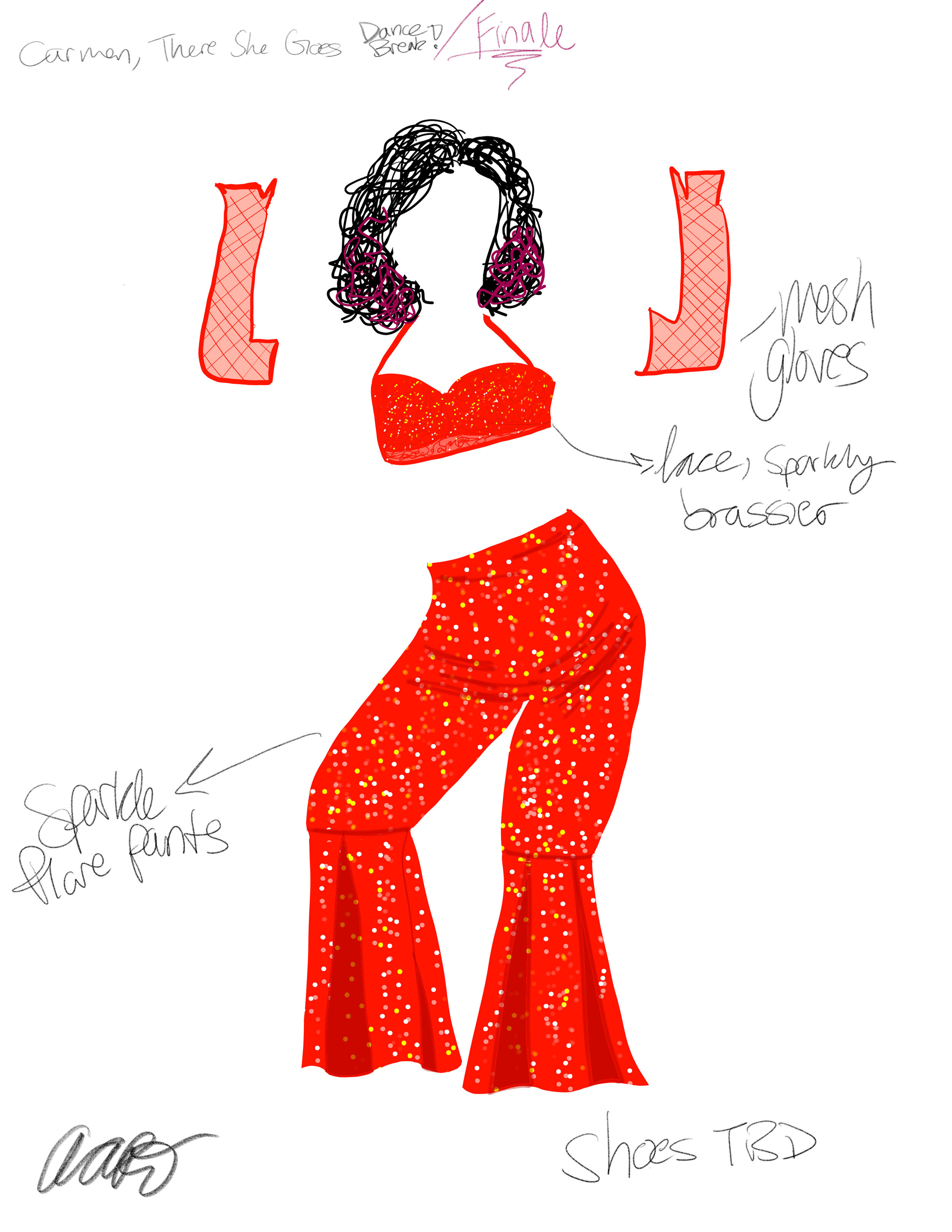

I don’t necessarily practice formal architecture on my own because it’s such a huge process to tackle, but I definitely do translate the skills I’ve learned in architecture to do other projects. I enjoy making cards for my friends, using whatever graphic skills I’ve acquired, or painting or drawing, stuff like that. I also like fashion, I like lines, my love of architecture and lines is very readily apparent everywhere. It’s not necessarily formal architecture but I think my love of design is kind of apparent in everything that I do and everything that I wear.

Are there any new projects you’re working on?

Yes, I am actually working on this project with my friend Krista who I did the lamp with, and we’re collaborating with a furniture studio based in LA. I’m not quite sure what form exactly that project is going to take, because we’re only in our second week, but it’s also a pretty short project. I guess more updates on that to come. I don’t know if it’s going to be furniture necessarily, but it’s going to be somewhere between furniture and objects and architecture. Very experimental and fun as always.

Do you feel like living in St. Louis and growing up there impacts your person, or impacts how you see and treat the architecture field in any way?

The first thing that comes to mind is how segregated St. Louis was when I was growing up, and the more that I come back the more integrated I see it has become. There are a lot more artists and a lot more people integrating with each other, but then at the same time, I see a lot more gentrification going on. I kind of have mixed feelings about that. It’s really great that all that is happening, and I’m very excited to see all these artists and designers and new restaurants and places coming up. I was always kind of uncomfortable or interested in how all these different worlds came together in St. Louis because I grew up in a predominantly white area and danced in the city, where it was mostly POC. I was like the only Asian person that I knew, really it was just a few of us. It’s exciting that through the arts St. Louis has become more integrated. I definitely would love to work there at some point or do some sort of project there because it’s a really interesting place. People kind of gloss over it because it’s in Missouri and no one really thinks much about Missouri, but there are definitely a lot of interesting things, a lot of different artists, and surprising things that I wish more people knew about.

Do you have any final notes or takeaways?

That’s mostly it! My brain isn’t functioning at its peak right now [laughs].

Say less, literally my brain is smooth [laughs]. Thank you so much for this!