Written by Sophie Paquette

I sort-of-met LaJuné McMillian like I sort-of-met a lot of people during my sophomore year: on Z**m. They joined my Dance Composition: Form class as a guest artist to present their epic workshop “Understanding, Transforming in Digital Spaces,” which introduced us to motion capture and avatar creation as methods of exploring dance and movement. The workshop operated specifically through the context of their Black Movement Project, a digital archive of Black motion capture data and Black character base models. Because my first experience with LaJuné and their work was through my laptop screen, this encounter carried with it all of the experiments, opportunities, and problematic precedents endemic to digital space. Finally seeing LaJuné’s work in a physical installation at Barnard College’s Movement Lab on October 8th was

When I enter the Movement Lab, I get to take off my shoes and sit on the floor, which still elicits a preschool-rug-adjacent excitement in me. I really have no formal dance background but I like to playact as someone whose art lives in their body. Moving image installations often ask that you locate yourself physically, finding a comfortable place to experience the art. For multiscreen installations like this one, this often means turning, calling on your peripheral vision, opening up your chest, leaning back. Recently I had the pleasure of visiting Wong Ping’s 4-channel animation installation at the New Museum, which offered its viewers a teal shag carpet and plush bean bags in the room’s center, with alternating screens such that the entire group would turn, together, at the end of one animation, moving as a unit to view the next. Maybe I just like being on the ground.

In the Lab, one wall played a film documenting LaJune’s recent installation at Brooklyn Public Library’s Central Library. As videos of Movement Portraits from LaJuné’s students and collaborators projected on the library, live performers danced in mocap suits for the audience outside of the library. At times, the projected videos were interspersed with dialogues by the moving artists, reflecting on their relationship to the image, the camera, Blackness and the body. Allowing for dialogue here also expands what we might consider “movement”--talking can be movement, laughing can be movement, hugging, loving, all can be movement.

Typical movement libraries might offer digital repositories of “anonymous” base models storing captured motions, able to be acquired and re-appended to any character. LaJuné’s movement portraits instead center the dancer--we see their face, their body, their spirit. Both during the live performance and in some of the projected portraits, dancers are often pictured wearing the motion capture suits, drawing attention to the embodied process that stores these movements. Process documentation is a form of memory, and LaJuné provides us with an archive.

Another element of this film that struck me was the often visible audience. Rather than attempt to obfuscate the boundary between mover and witness--as movement libraries often do, allowing us to select and store captured moments without any knowledge of the body or person who engendered them--this piece draws attention to the relationship between performer and audience, honoring the movement as an embodied moment in time, experienced by all those occupying its space.

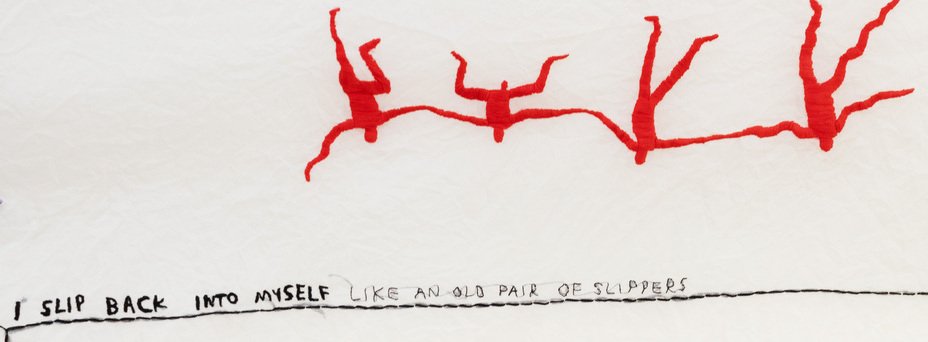

On the adjacent wall, two screens played LaJuné’s Black Movement Project, atmospheric and mesmerising videos using 3D animated avatars and motion capture. Unlike the Movement Portrait film, these videos abstract the body, depict a body continuous with its environment, and shatter the received hierarchy that typically delineates bone from muscle, muscle from skin, skin from space. Here, the body is a suggestion: there are moments when the body bleeds through the background, when it becomes the background; avatars whose skins are permeable, mustable mesh, whose arms can pass through their stomachs, whose stomachs can be their arms.

In the Movement Portraits films, when describing Blackness and their identity, one of the performers says: “I think spirit, I think energy, I think love.” In this animated video, LaJuné extends the body into these metaphysical realms, exploring movement through dancers who look like water, who distort and expand, who leave trails of light in their paths. The bodies duplicate, reflect. The two screens show the same video, but flipped vertically, asking us to recontextualize space and orientation, focusing on the body as amorphous shape and lines rather than a received structure.

In this space, the light from one projection casts a glow on another--the screens, somehow communicating. I turn to look at a separate screen, and when I return to the animation, a body will have become entirely shards of light. Duplication allows a form to dance with itself, almost in an embrace.