Written by Korrin Lee

Alejandra Ghersi’s musical catalog under the name Arca is and has been revolutionary both musically and corporeally. Arca’s body of work thus far is unarguably queer, from the lyrics in “Piel” to the single “Nonbinary” to her unapologetic presence as a Venezuelan trans woman. Combining sound and visuals, KicK iii creates a queer mode of existence that encapsulates just a fraction of what it means to resist being.

Arca is a multitude of things—a collection of self-states, or distinctly different versions of oneself, that come together to create music that exists across genres, without bounds. Arca’s five-part electronic epic traverses these self-states with each entry into the Kick universe that Arca has carefully crafted since the release of KiCk i in 2020. The Kick universe embodies transformation and the process of becoming, with KiCk i coinciding with Arca publicly coming out as transgender. The name “kick” in all its different capitalizations comes from the prenatal kick that serves as the first instance of individuation from the parent. The following four albums were released consecutively over four days in late November of 2021, each album exploring different genres and moods, ending with the introspective piano of kiCK iiiii.

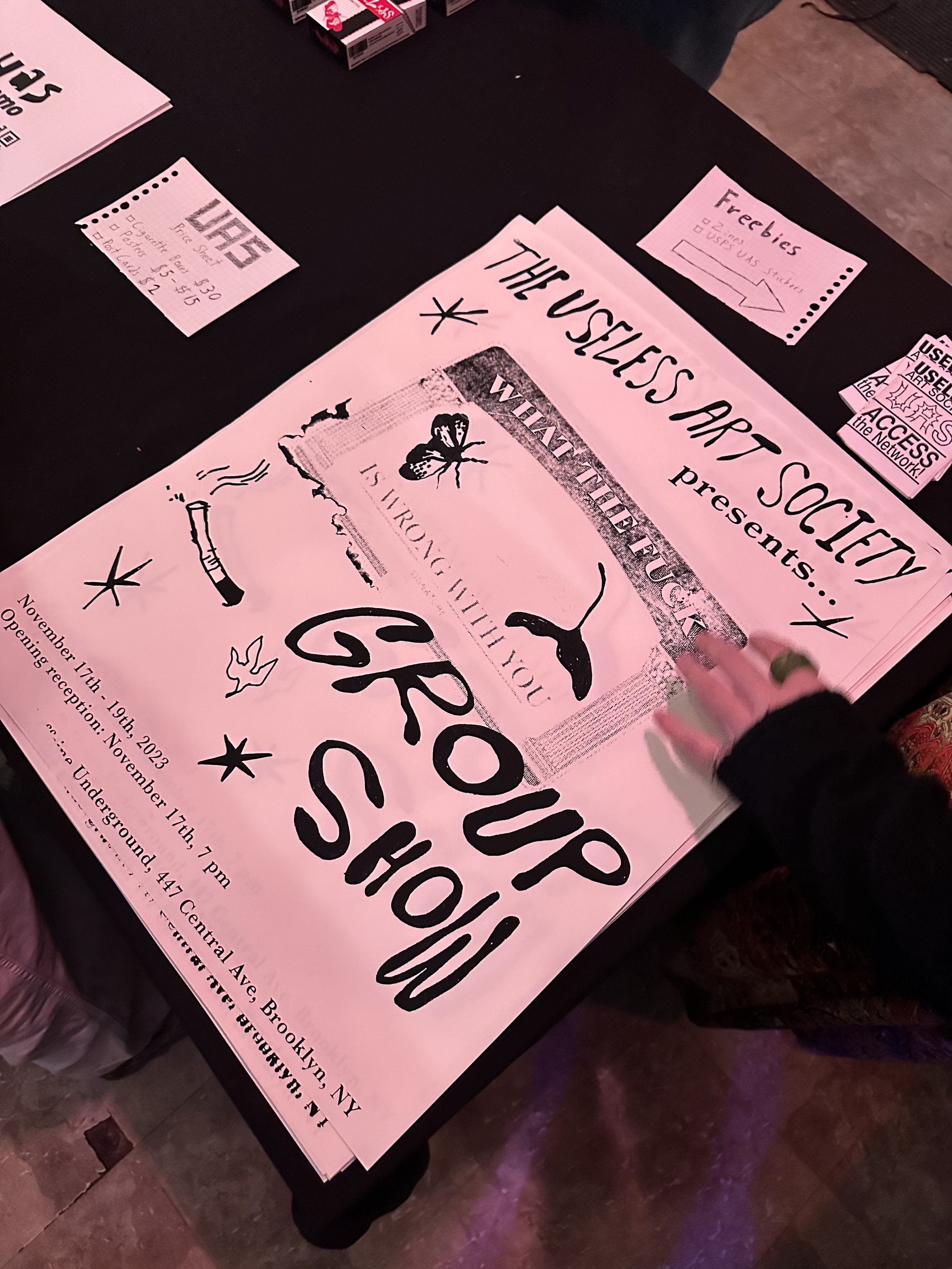

Arca, Courtesy of unax lafuente

KicK iii is a jolting wake-up from the robotic introspection of “Andro” from KICK ii, starting with the explosive noises of “Bruja” and ending with the ethereal beauty of “Joya”—it is perfectly unpredictable. Through listening, we catch glimpses of other states of being, of what it feels like to be Electra Rex, and what it feels like to traverse a range of self-states. The very concept of self-states, first introduced to us by the lyrics of “Nonbinary,” embraces the idea of the multiplicity of the body and self, especially with regard to the transgender experience. Gender is constantly shifting—there are no set standards, only a continuously changing experience of our inner and outer lives. It is in this way that self-states embrace the process of reckoning with gender and oneself, confronting the variants of us among our past and present selves.

For Arca's identity as an artist, the visuals are equally important as the songs. They combine the real and the metaphysical through digital depictions of herself in the accompanying visuals for “Nonbinary” and “Prada/Rakata,” thus extending the self to the digital realm. Within these visual representations, Arca creates an outlet for gender expressions that aren’t yet possible in real life. Arca, seemingly dead, drapes herself artfully on a floating rock with robotic bugs, evoking a sense of death and rebirth in the process of decay. Translucent humanoid surgeons operate on a pregnant Arca, and two Arca’s, one in white and the other in black, argue with each other, while a mutiny of Arcas are dancing in sync. The trans symbol is burned into the ground around her and etched into the foreheads of those at the base of a machine mermaid Arca, and there are glimpses of the phrase “second puberty” throughout the entirety of the video. Arca’s work celebrates what it means to move into a new body and undergo a second puberty, the birth of someone new within yourself. Though a “second puberty” is an experience that many people born female go through as they enter their twenties, it is also a term unique to the transgender community as it describes the period of physical and emotional change after taking hormone replacement therapy. This phrase is a recurring motif in the “Prada/Rakata” video, further highlighting and celebrating the trans experience as one that is simultaneously rooted in the body and transcends corporeality. Through her previous visuals, Arca paints a picture of transness and self-determination as a process that requires multiple selves coming together to create something new, setting the stage for KicK iii’s unavoidably queer exploration of the body and sexuality.

KicK iii album cover

At first glance, the album art for KicK iii is eye-catching, chaotic, and otherworldly; the central figure is a two-headed Arca with two sets of wings surrounded by two-headed skeletons on leashes serving rattlesnakes, flowers, and octopus. There’s a contrast in makeup between the two faces—one with a bold red lip and the other with iridescent eyeliner—and almost illegible marks on her wings. The album cover screams duality: the two-headed skeletons are the only ones that are “alive,” there are carcasses of single-headed animals and skeletons crushed on the ground, and the weapon she is holding is simultaneously a gun and a sword. Arca herself is made out of pairs, putting forth an image that speaks to the complex landscape of Arca and KicK iii. Arca is making herself abundantly clear: out with the singular and in with the dual, or the infinite. On her wings there seems to be some type of writing, either etched in or drawn on: “blood faggot”, “monster”, “puta”, “whore”, and “tranny”. It appears as though someone else has done this. The words are backward as if someone wrote them from behind rather than in front of a mirror. As our eyes draw away from the center of the image, we see the boundaries of the stage that Arca occupies, which seems to be in an industrial warehouse setting. Is this an exhibit? Who manufactured it? What is real and how do we know it? KicK iii is here to make you ask questions, to consider the queer nature of life and death and of body and self.

Notably, the only music video accompanying the tracks on KicK iii is “Electra Rex”, which does not use digital renditions of Arca, unlike their previously released Prada/Rakata video (the only other visual for the kick series). Following the first notes of the song, the camera guides us past a line of models of a queer fashion show that never happened, sporting looks that exist outside the binary, and ultimately, we reach her. Arca remains the focal point of the video from this point on, as we see her thrashing around away from the group and later rejoining the queer mass, introducing us to a giant queer orgy. They are dancing, crawling, and also having sex all at once, demonstrating the body as an instrument without any formal bounds. The lyrics beckon the listener to join them, “let your hips go,” to dance like Arca, to unleash what you already know and feel. The atmosphere of this video is unequivocably queer, embracing the unorthodox and gender non-conforming looks of the models and encouraging self-expression through any avenue. Though the video accompanying Electra Rex contrasts in medium from Prada/Rakata, both invite the viewer to break free from the confines of the gender binary and corporeality.

To further understand Electra Rex, we must understand that Electra rex is a self-state of Arca’s, one that is a merging of Oedipus Rex and Electra that kills both parents, has sex with itself, and subsequently chooses to live. Electra Rex’s existence extends past the album; it is a rejection of the binary and a celebration of the sexual. Electra is not simply just an alternate name for Arca, but an entirely different person; Arca describes Electra Rex as mischievous but with good intentions, further separating herself from the identity of her alters, of which she has a cast. Thus, Electra Rex occupies an important place in Arca’s identity as an artist and as a person, encouraging avante-garde expressions of sexuality and queerness. However, Electra Rex is not the first time that a self-state has been addressed in Arca’s work. Xen, after which her 2015 album is named, originated from an online identity that was an early form of gender expression for Arca. Xen acted as a medium through which a young Arca explored gender, it was an outlet for the self that can only safely exist online and quasi-anonymously, for Arca to be a girl and to be in love with somebody that saw that version of her. Arca’s album Xen brought back Xen, honoring her as an integral part of Arca’s identity, a self-state that tenderly held the beginnings of gender euphoria, rather than something to bury.

Courtesy of unax lafuente

For many queer people, existing as a “different” person online was an important way by which we were able to explore our relationships with gender and our ideal self. It might be easy to consider the digital version of ourselves as wholly separate, but this only supports the “notion that what happens online does not have the capacity to impact and affect real change,” which confines the consequences of the digital to the online sphere. Instead, we should reimagine the relationship between the online and the offline as a symbiotic one that constantly shapes our awareness of ourselves and the world around us. In the digital age, it is important to honor the parts of ourselves that are not yet ready to exist outside of the online. They are as much a part of us as any of our offline selves are. Arca’s description of self-states such as Xen and Electra Rex provides a channel through which we can describe ourselves in a way that honors every single part, even the ones that we want to hide. Electra Rex is an inarguably queer character, from her inception to her personality, one that further encourages a carefree queer expression of desire and being.

KicK iii creates a statement of multiplicity both sonically and visually that refuses to be categorized, that is quintessentially Arca in every way possible. From the album artwork to the sonic landscape to the various self-states that the listener traverses, KicK iii is a call toward a new imagining of what it means to occupy the body and the mind. Instead of limiting ourselves to one fixed identity, KicK iii creates the space for multiple iterations of the self to exist, to embody the contradictions and fleeting sentiments that we know but cannot name. Arca’s concept of self-states presents a mode of being that rejects the singularity of a cis-het hegemony and encourages self-exploration in its purest form. Queer existence as plural and without shame is a threat to power structures that function off of the production of shame and the continued shunning of those who are different. Through the lens of multiplicity that Arca puts forth in KicK iii, the body, in various different forms, acts as a vessel through which we can project our truest desires, even if those desires are intangible at present.

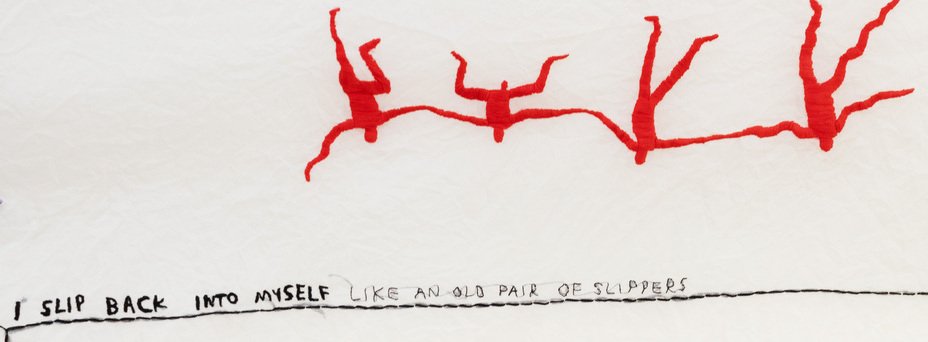

As someone who identifies as trans, this concept of multiple selves particularly resonates with the ways by which my younger self fractured off into separate identities for protection. My online identity was a means by which I was able to break free from the femininity that was forced onto me. Reflecting on my many selves throughout the years, I can now appreciate each one’s purpose in building the person that I am today. So, let us abandon the static of one identity and venture towards new possibilities and what it means to exist across space and time as multiple people, honoring every part of ourselves in our construction of the queer body.

Writer Korrin Lee’s wall full of Arca imagery