Written by Beatrice Agbi

The words Rushing headlong into new silence, or I wouldn’t have known if I didn’t stay home, or The trees liked the wind, may sound familiar to you if you regularly ride the subway. The phrases are the first lines to “Smelling the Wind,” (Audre Lorde) “A Night in a World,” (Heather McHugh) and “Faithful Forest,” (Alberto Ríos) – all poems displayed on the NYC subway. Perhaps you have read these words in a crowded train car as an attempt to distract yourself from the hot breath of the person standing behind you. Or you’ve skimmed them on your way back to campus at 3am, while leaning your head on your friend’s shoulder.

You’ve seen the poems so many times before that looking at the poster becomes courtesy – after seeing the first line, you could recite the rest to yourself word for word. Most times, you don’t think about their meaning. But when you do, you wonder: Who decided to put Audre Lorde on a train? What does a poem about trees have to do with the transit experience? Who makes these decisions?

These poems are part of the “Poetry in Motion” program, founded in 1992 by the MTA and the Poetry Society of America. At its inception, the initiative displayed only four poems on overhead car cards: an excerpt from "Crossing Brooklyn Ferry" by Walt Whitman, "Hope is the thing with feathers" by Emily Dickinson, "When You Are Old" by William Butler Yeats, and "Let There Be New Flowering" by Lucille Clifton. After a brief break between 2008 and 2012, in which the program was replaced with a similar minded prose initiative called “Train of Thought,” the initiative returned under the administrative jurisdiction of MTA Arts & Design. As part of its re-establishment, not only were the poems moved to the poster cards that they are on now, but each piece of artwork shown on the poem’s poster card depicts an actual art installation in the NYC transit system. Providing those interested with a fascinating web of subway lore, this move is meant to create “synergy between the disciplines,” according to the Poetry in Motion Website.

1993 picture of a passenger looking at a poem on an overhead car card. Courtesy of The New Yorker. Photograph by Jim Cooper

A passenger looking at a poem displayed on a poster card. Courtesy of The New York Times. Photograph by Johnny Milano.

Poems chosen “must be no more than 10 or 12 lines and must be something that every subway rider would be able to appreciate,” said Matt Brogan, the executive director of the Poetry Society of America, to The New York Times. “The aim is to provide an illuminating experience and opportunity to pause in an environment where riders often feel distracted or rushed.”

Open-ended criterias such as these are why the Poetry in Motion program has been able to display a variety of works, featuring over 200 poems since its debut. With works by Shakespeare, Henry David Thoreau, William Butler Yeats, Maya Angelou, and former US Poet Laureate Tracy K. Smith, the power of Poetry In Motion lies in its ability to connect commuters with a diverse array of poets, whose works serve to provide train riders with profound moments of insight. Their words bring pause to a commuter experience which often prioritizes efficiency over personal interactions.

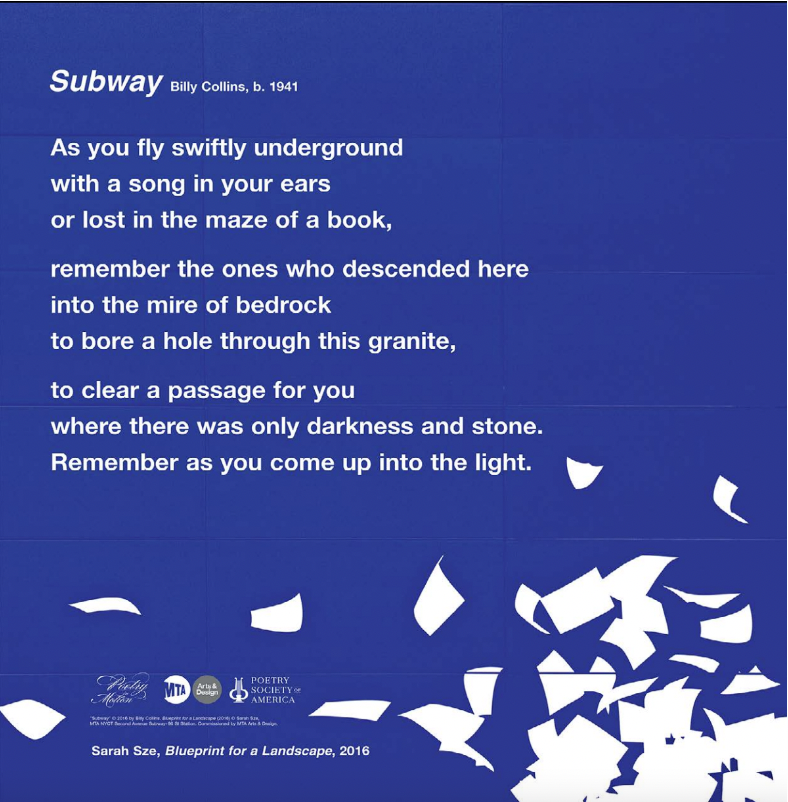

Some of these poems are directly related to the subway experience. Consider “Subway,” by Billy Collins:

As you fly swiftly underground

with a song in your ears

or lost in the maze of the book,

remember the ones who descended here

into the mire of a bedrock

to bore a hole through this granite

To clear a passage for you

Where there was only darkness and stone.

Remember as you come up into the light.

Collins’ words call on us to pause from our daily routines and engage in a moment of mindfulness. He uses the contrast between dark and light to emphasize the distinction between past and present, between those who sacrificed time in the darkness so that we could move forward with our current lives above ground. His work is accompanied by a picture of Sarah Sze’s “Blueprint for a Landscape,” which can be found in the Q Train’s 96th Street station. Her artwork gives the poem a dark blue background, a color that appears to be the same as the one used in blueprints. Thus, Sze’s art enhances the poem’s theme of construction, bringing awareness to the city’s foundational history and prompting, perhaps, a Google Search on how thousands of workers managed to lay more than 665 miles of railwork.

Image of Subway as it appears in transit. Courtesy of the MTA’s Poetry in Motion Guide.

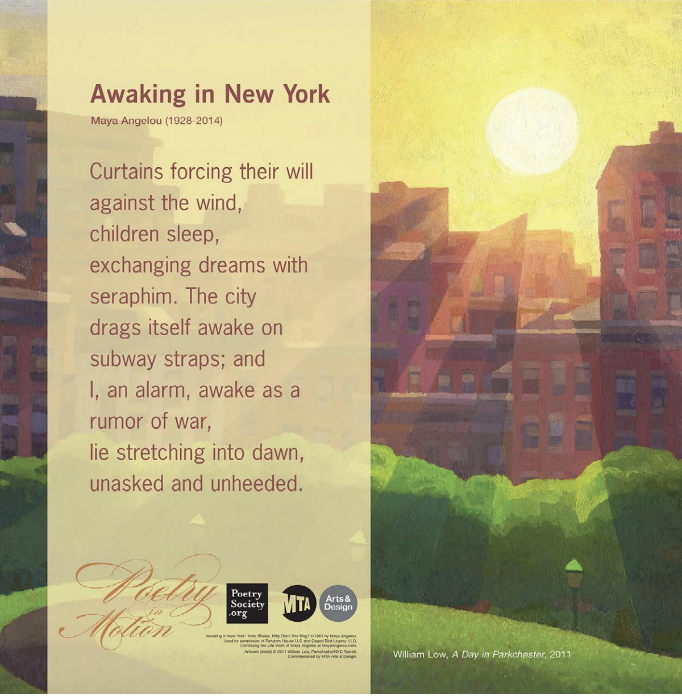

The poem, “Awaking in New York,” by Maya Angelou, is more a reference to the daily lives of all New Yorkers. She begins by setting the scene:

Curtains forcing their will

against the wind,

children asleep

exchanging dreams with seraphim.

Such imagery is accompanied by William Low’s “A Day in Parkchester,” which can be found at the 6 train's Parkchester Street station. The artwork shows the morning sun rising over a cluster of apartment buildings, providing an exact visual to the lines which describe the city in the morning. One can almost imagine that the early morning images Angelou references take place in the apartments depicted in Low’s picture. She continues:

The city

drags itself awake on subway straps,

The city here is a metonym for the morning commuters, those headed to school or work, who stare at the morning sun from the windows of their aboveground train captured by Low’s picture. To them, she offers words of encouragement:

I, an alarm, awake as a

rumor of war,

lie stretching into dawn

unasked and unheeded.

The “I” here feels universal. It is not just Maya Angelou, but every New Yorker reading her words, who is about to begin their day. Wake up, Angelou tells her audience, you/I have a world to take on, “unasked and unheeded.” Here, Angelou’s poem and Low’s picture serve as a literal illumination; they are akin to the dawn, working to wake New York up in preparation for a new day.

Image of Awaking in New York as it appears in transit. Courtesy of the MTA’s Poetry in Motion Guide.

One of my personal favorites, “Smelling the Wind,” by Audre Lorde, subtly speaks to the theme of traveling. Lorde writes:

Rushing headlong

into new silence

your face

dips on my horizon

the name

of a cherished dream

riding my anchor

one sweet season

to cast off

on another voyage

No reckoning allowed

save the marvelous arithmetics

of distance

Since the narrator of this poem appears to be speaking to a loved one that they are traveling to meet, whose “face dips on [their] horizon,” this piece, at first glance, only seems tangentially related to the subway experience. Although this poem appears to exist in odds with the present surroundings of its environment, it asks a question that is useful to the lives of commuters. As we, on this train, “rush headlong into new silence,” whose face dips on our horizons? Who (or what) are we rushing to? Just as Collins asks us to be mindful of those who built the train, Lorde’s poem asks us to be mindful of for whom we “brave the marvelous arithmetics of distance.”

Personally, when I read this poem, I feel as though I am hurtling through time to face Audre Lorde. The image of her that accompanies this poem is a glass mosaic titled “Beacons,” by Rico Gatson. It can be found at the 167th street station for the B and D trains. When I look at this picture of her, surrounded by multicolored beams of light, the glow she radiates is akin to that of the sun. Her face is the one which dips on my horizon. My own personal illumination.

Image of Smelling the Wind as it appears in transit. Courtesy of the MTA’s Poetry in Motion Guide.

Another one of my favorites, “Stationary,” by Agha Shahid Ali, is the most recent poem added to the transit collection. Like Lorde’s and unlike Collins’ piece, it appears to be loosely connected to the transit system. But I like it for its tone of urgency.

The moon did not become the sun.

It just fell on the desert

in great sheets, reams

of silver handmade by you.

The night is your cottage industry now,

the day is your brisk emporium.

The world is full of paper.

Write to me.

These lines feel like a call to action. It is as though Ali is handing the city over to me, as if the world is mine to be penned onto paper. “Write to me,” he commands. This order applies not just to writers or lovers, but to all its readers. If the world is our “brisk emporium,” then to whom will we dedicate our thoughts? This poem, as with Lorde’s, asks us to consider our relationships with that which is meaningful to us––whether it be a lover, a family member, or a job.

Image of Stationary as it appears in transit. Courtesy of the Poetry in Motion Website.

This poem is accompanied by Jim Hodges’ I Dreamed of a World and Called it Love, a piece of art which can be found at the Grand Central–42 Street station. With a mixture of blues, oranges, and silvers, the artist here took a combination of colors and made it his own, expressing his vision of the world and naming it Love. Although he is not writing, it is almost as if Hodges’ work obeys the final command of Ali’s poem. Write to me. Hodges has, in a sense, penned his world onto paper.

The Poetry in Motion posters have created an interesting narrative throughout the transit system. Each poem speaks to one another, providing readers with a moment of mindfulness and peace. The initiative’s aim of supplementing New Yorkers with literature has inspired similarly minded programs in public transit systems across various cities throughout the country, from Los Angeles to Washington DC. As millions of commuters nationwide find their illuminating experiences in poetry, the initiative’s national success is a testament to the ways in which literature can speak to our lived experiences, motivating us to consider the present realities of our existence . Or, at the very least, it gives us something nice to look at between transfers.