Written by Karen Cheng

Lay your burden down

Look to the sky [1]

It was an unacceptably cold Sunday in late March when, feeling the metaphorical stickiness of my Columbia dorm room, I discarded my homework to instead take the 2 train down to Brooklyn Heights. My shivering body scurried its way over to Picture Room, a cozy gallery on the corner of Atlantic Avenue and Henry Street. Nestled between a hipster, very Brooklyn cafe and a nondescript memorial chapel, I was greeted by the views of a snowy New York Harbor, and not much else. I was alone, urgently alone, in the best way possible.

Trilemma, 2022

I’d been yearning to see Cécile McLorin Salvant’s art exhibition “Ghost Song” since it opened on March 3rd. I’d begged my friends to attend this really cool opening with me this weekend and that the artist herself will be in attendance!, but my enthusiasm bore no fruit. Instead, my night was spent listening to Salvant’s new jazz album, also entitled Ghost Song, on my lonesome.

I first encountered Salvant by way of her songs, which I was introduced to as a senior in high school. The memory is indelibly inked into my mind: watching the Houston sunset from the trunk of my Nissan Rogue, my jazz friend (I always seem to have at least one) took over the aux, and Salvant’s voice boomed through the car’s shitty radio. It was a cover of Aretha Franklin’s “One Step Ahead,” the top hit from her 2018 album, The Window. “Cover” seems too trite a word for her ethereal, raw, and at times frantic rendition of the sultry classic, which brought us to a contemplative silence. The moment was brief: the song ended, Kendrick was next on the queue, and we cracked open another seltzer.

Here in your arms

Where the world is impossibly still [2]

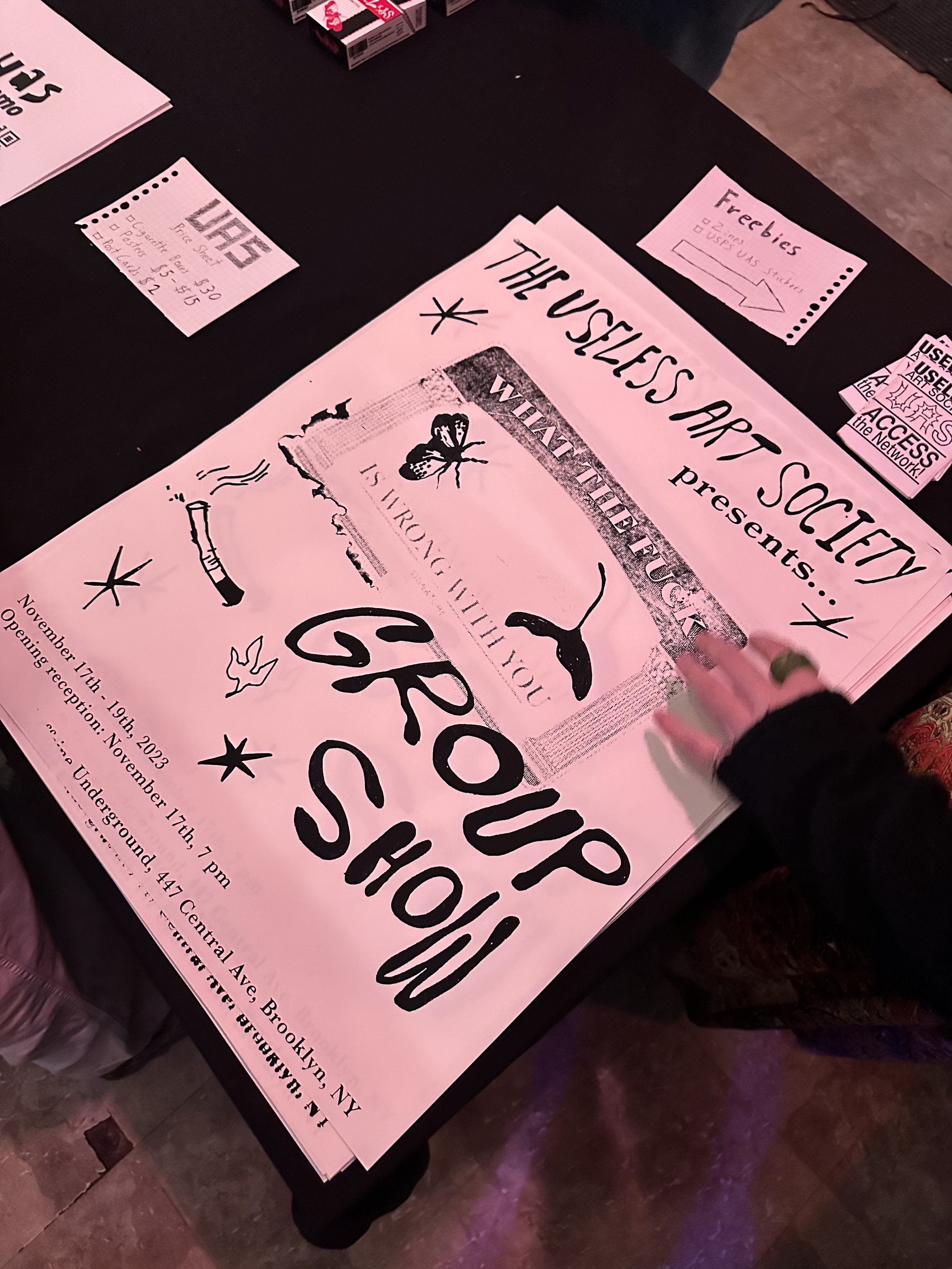

Complementing her generative career in modern jazz is an eye for the tactile medium of embroidery––the focus of Salvant’s exhibit here at Picture Room. My “Ghost Song” viewing experience begins outside the gallery’s entrance, where I am met by an encompassing yet uncomplicated window display. As I snap a picture, the atmosphere behind me––pre-war apartments, spiderly leafless trees, a sheet-white sky, the rough outline of my own bundled-up figure––reflects back onto the glass, the messiness of the city backscattering its way onto an intricately embroidered organza. Despite the blistering wind outside, I am compelled to take a breath, pause, and look:

Dom Sub Dom Tom, 2021

The first thing I notice on the sheer silk is the text “How to establish a daily writing practice:” (I, too, wonder how this might be done––the answer remains unfound, here as elsewhere). Above, a whimsically demonic creature exhales a softly lustered green, bordered by the titular words “DOM SUB DOM TOM.” This playful, rhyming phrase, “Dom-Tom,” is actually an acronym for French overseas territories, I learn. A hint of something sweet-sounding, childlike even, asserts itself into the complicated and violent history of French colonialism.

This theme––the interruption of the playful with the serious––promulgates across Salvant’s work. Joyful, fantastical, whimsical; melancholy, meaningful, dynamic. It presents itself aesthetically, too, by nature of the craft: in each haphazard, diary-like “scribble,” I imagine the intentional practice of carefully, tangibly, hand-sewing each element from a wispy spool of thread. A merging of two contraries; violent and joyous; meticulous and messy. The components of a daily writing practice, perhaps?

I've come home, I'm so cold

Let me in your window [3]

In my experience, art galleries are almost always empty, aside from an exhibition’s opening night. To open the door to James Fuentes or David Zwirner is less daunting in a group of friends, who shield you from feelings of non-belonging––a receptionist’s cold gaze, the echoing creak of wood beneath your footsteps. But standing outside in the unrelenting cold, my toes begin to go numb. My body won’t allow time to think about the social ramifications of entering this lofty gallery alone. I open the door with a colorless hand.

I am the lone spectator here, but the hesitation caused by this fact fades quickly. The comforting warmth of the radiator helps, but it is mostly Salvant that makes me feel at home. With her song playing through my earbuds, her words and images in my sight, my mind is brashly immersed in her world. I take a dive into her dreamscape.

Moon Song, 2019

Trilemma, 2022

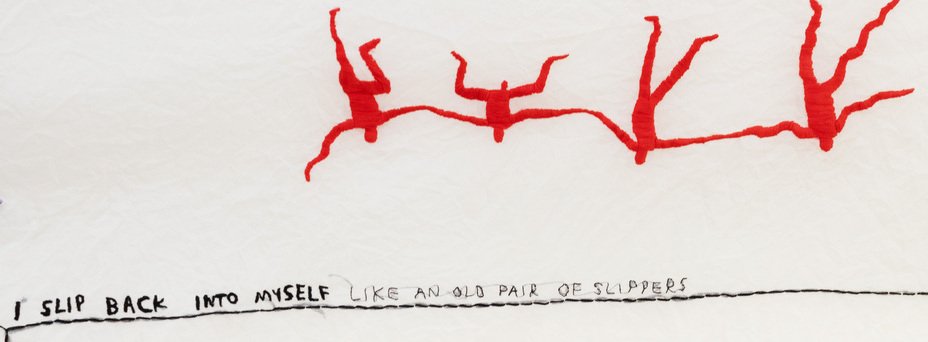

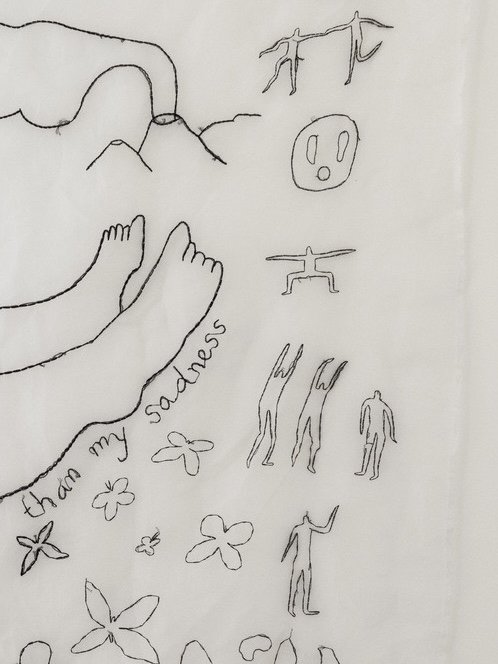

My urge was greater than my sadness, 2020

Layers of sheer, crinkly silk and linen feature images with intricate yet obviously manual touches. This parallels the way her voice sings to me, in its calculated yet earthly manner. Look closely: the fabric contorts where the stitches are especially tight, as if fighting to make space for her sewn creations. When the sun shines through the gallery’s large windows, the silk’s transparency multiplies, allowing another piece of hers to bleed through. My body, too, emphasizes the tapestry’s malleability, the weightless fabric withering in my steps. We are in a dance.

Look closer: loose, uncut threads hang from skin, like an unplucked, forgotten strand of hair. There is a vulnerability in each character’s stitched-together existence. I recall how, on the train here, Salvant told me (through an interview I read on my phone): “I want my music and my art to feel like you’re opening someone’s diary - there’s an old ticket stub for something, a quote, an idea and frustration and a secret.” In the gallery, listening to her album, existing among her textiles, I am intimately, vulnerably in Cecilé’s world.

Lounging on the sands of my hourglass

Watching the time drip [4]

In her albums, Salvant weaves together covers and original music. In the same way that these covers become her own––from Sting to Kate Bush to West Side Story––so do her embroideries, which draw from a variety of external references to create a new originality.

One reference that caught my eye, and confirmed the benefits of a liberal arts education: Hildegard Von Bingen, who, my Music Humanities professor will tell you, was an 11th-century nun, musician, and mystic that praised the prophetic power of music. After the church forbade her from making music, Hildegard wrote that it is Adam who possesses “the sound of all harmony and the sweetness of the entire musical art.” To make music, to talk about music, to make art about music, then, is to access part of this divine spirituality.

Hildegard Von Bingen, 2020

There’s something special about the way Cecilé incorporates other people’s work into her own. It’s like we are having a conversation with all of these sources, spanning centuries and crossing genres. “Ghost Song” is a bibliographical reflection of herself that surpasses tradition or form. And when you enter the gallery, you, yourself become another footnote.

Peace and quiet and open air

Wait for us somewhere [5]

46 minutes and 6 seconds of the Ghost Song album later, my visit to the gallery had come to a close. I recuperated at the aforementioned coffee shop, where it struck me that the barista was the first person I’d spoken to all day. My entire waking hours were spent in silence, save for a slight “hello” or “excuse me,” but this moment was the first fully-formed sentence I’d consciously uttered. Like breaking a spell, a cerebral realization came over me: I had lived entirely in my own mind that day, in a waking dream full of vibrance. Cecilé and I had shared a slice of the afternoon together, with no one else to distract. Part of this vulnerable, intimate experience had arisen from visiting the Picture Room on my own; an experience I urge you to try, even just once.

On my walk home: I gaze one last time at the window of Picture Room, at the Dom-Tom’s outstretched hand. In the reflection, a young couple walks past, wrapped in one another’s warmth. Seeing me stare through the window, they follow suit. They converse:

“This looks cool.”

“Yeah. So beautiful.”

“Should we check it out?”

“Sure. Are they open? There’s no one inside.”

The doorknob turns softly with a hesitant hand. A bell jingles. They enter; I smile.

Ghost Song the exhibition is on view at Picture Room until May 1st. You can listen to the album Ghost Song here.

[1] “Thunderclouds,” 2022

[2] “Until,” 2022.

[3] “Wuthering Heights,” 2022.

[4] “I Lost My Mind,” 2022

[5] “Somewhere,” 2018.