Written by Eve Rosenblum

The show opened with a conference table, one harsh light revealing the dancers dressed in business clothing. “Who is this?” “Who are you?” The dancers’ bodies gyrated to the dialogue as though possessed by some capitalist demon.

Was this class commentary or just a music piece? At points I thought there might have been a narrative, a corporate executive visits the underlings to reprimand them, only to be trapped there. But when the underlings returned and the executives exited, the visual language was broken and the audience confused. “I thought it was about God,” my friend told me afterwards.

The work-wear special kicked off Fall For Dance’s 20th annual festival in New York City Center, part of a two-week run boasting two world premiers and continent-spanning performances. Its reputation is in part based on its affordability; tickets are no more than twenty dollars and sold by lottery at the beginning of September.

The two nights I went struggled to preserve the show’s stellar reputation. Both featured solo-dancer, musician combos – the first night, tap-sody and blues, the second, ballet and baritone. Not expecting such equality of sight and sound, novelty engaged me with these two performances. But where energy carried, substance did not. I regretted that there were not more dancers to add emotional gravitas to the performances or more musicians to complicate the scores. The relationship between musicians and dancers was curious at first, but lacked the engagement necessary to sustain interest throughout the pieces.

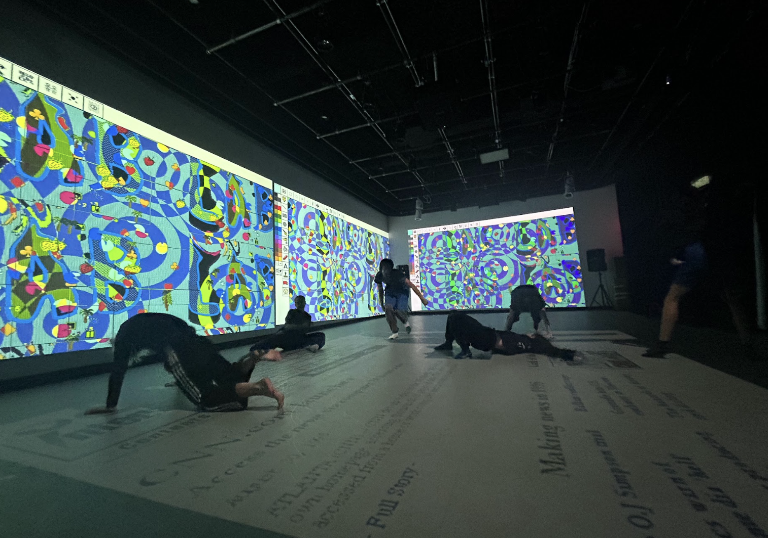

The introspective performances were balanced by longer modern ensemble pieces. In Program One, New York’s Gibney Company decorated the stage with speakers and their bodies in sheer, neutral clothing. The music changed repeatedly, from soul, to techno, to pop, as the dancers paired off or clumped, at one point, circling like children.

Program Two featured another big ensemble piece, indistinguishable from Program one’s aside from the choice of black rather than beige costumes. At the height of both, dancers spoke to each other with their bodies. The talented Jie-Hung Shau moved between her partners: from lust, into conflict, and, finally, resignation. More was said than what any dialogue could give expression to.

At its best, Fall for Dance showcases wonderful performers from around the globe right here in New York City. At its worst, it offers intangible pieces for its “uninstructed audience.” Access and unconventionality have earned the festival its reputation. In its 21st year can we hope for more consistency?