Written by Caterina Newman

Even before I knew anything about Hilma Af Klint and the context of her works, I was captivated by The Ten Largest: expansive compositions of geometric swirls and buoyant circles depicted in dusty pastels with some deep shades of blue. The works famously contain unclear lettering such as the “W” and I became curious to find out why. As I learned more about Af Klint’s life and role in art history, I discovered her less exhibited works. In fact, most of Af Klint’s works haven’t been exhibited, but she is just now starting to gain the attention she deserves.

Art historians ignored Hilma Af Klint despite her abstract works preceding revolutionary abstractionists like Kandinsky, Mondrian, and Malevich in the 20th century. As an unmarried woman and a theosophist, her status as a professionally trained artist wasn’t recognized during her time or much after. Af Klint knew her work wasn't well received. This likely liberated her from public scrutiny and made her free to create as she pleased. She prohibited any of her works from being exhibited up to 20 years after her death. She died in 1944. However, it was 42 years later that Af Klint’s work was first exhibited at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Hilma Af Klint was part of a group of women who engaged in seances and spiritualism known as “The Five.” She involved herself with thinkers of religion and philosophy, most notably with Rudolph Steiner, the founder of Anthroposophy. Af Klint gifted Steiner the series of watercolor prints Tree of Knowledge.

Most recently, the Tree of Knowledge (the series of eight works that was gifted to Steiner) has been exhibited at David Zwirner’s 69th street gallery from November 2021 to January 2022.

The unique opportunity to see the Tree of Knowledge required an appointment at Zwirner’s. On a Saturday afternoon, I visited the gallery’s 2nd floor where the exhibition room was painted a muted dark gray. The room was populated with a single bench in the center and a fireplace on the opposite-facing wall of the artworks. Lined in a straight row, the eight watercolor works were individually illuminated by overhead lights.

Hilma Af Klint. Tree of Knowledge. Watercolor, gouache, graphite, and ink on paper in 8 parts.

I was not expecting to only see eight works. However, these eight works were a lot to digest. The content was very detailed: consisting of nursery pastels and miniscule brushwork. I tried to take my time, but felt pressure to move down the line of works as people kept filing into the gallery room. I took a step back and waited for there to be a break in the groups of people. I watched at least 3-time slot appointment groups come and go, finding brief moments to take a step forward, zoom in and take it all in.

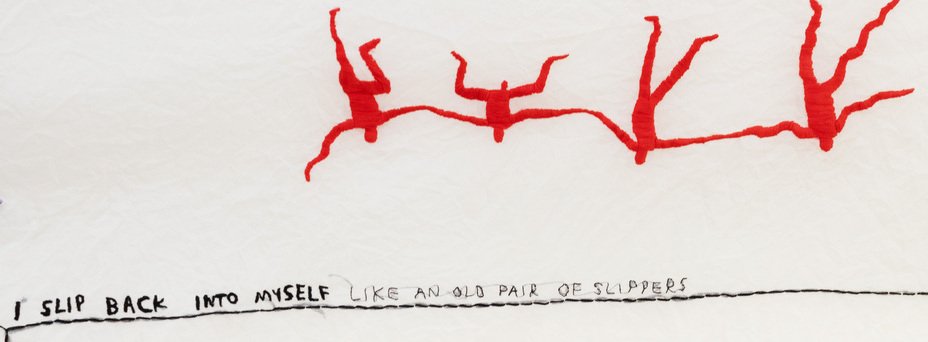

I watched the lifespan of those three viewing groups, coming in and out, almost rhythmically timed. Lifespan and movement are major themes for Hilma, and I immediately picked up on the movement of my own viewing experience. Not only was I in motion: taking a step back, squinting my eyes, and coming up close, but so were the artworks. This movement within the works manifested as the collective progression of the eight works from left to right. To me, I interpreted this movement as a transition between the works, in groupings of two. For example, the first two works are one grouping in which the second print is the evolved version of the first work. For the third grouping, the fifth and sixth prints in the series, this layered transition takes the form of a magnification.

(Left) Hilma Af Klint. Tree of Knowledge, No. 5, 1913-1915. Watercolor, gouache, graphite, and ink on paper. 18 x 11 ⅝ inches

(Right) Hilma Af Klint. Tree of Knowledge, No. 6, 1913-1915. Watercolor, gouache, graphite, and ink on paper. 18 x 11 ⅝ inches

It reminded me of the movement of a camera lens: it moves in a spiral as it zooms and reveals a more detailed image. This aspect in which the works progressively evolve into new images is what I understand to be Hilma Af Klint depicting a human lifespan where one stage evolves into another. Evolution is a consistent theme in Af Klint’s oeuvre. According to Birnbaum & Enderby in Painting the Unseen, “logarithmic spirals and tendrils represent evolution”, which also speaks to my impression of the camera lens magnifying in the shape of a spiral.

Af Klint intended for her paintings to only be revealed in the far future as she believed her works were truths she gained through her seances.

In Af Klint’s work, she has created symbolic language through colors and recurring images. Noting it all down in her notebooks, the artistic language is still complex and undecipherable to an extent. However, according to Birnbaum & Enderby in Painting the Unseen, art historians have been able to detect connections such as “the color yellow and roses stand for masculinity; color blue and lilies denote femininity.” Af Klint’s ideas on gender roles challenge the heterosexual matrix, allowing the overlapping and intersection of masculinity and femininity. She further expanded on this through the incorporation of the letter W as a subtle critique of an influential scholar at the time. Austrian philosopher, Otto Weininger assigned the female to the letter W in his works that attempt to theorize women as inferior and unable to produce anything of importance, Hilma incorporated the letter “W” in her works, assigning it a new definition. According to Birnbaum & Enderby, functioning as a criticism of Weininger, Af Klint journaled that “The letter U stands for the spiritual world, opposing W for matter; the ancient vesica piscis (the intersection of two overlapping discs) signifies its traditional theme of unity, creation, and inviolability of geometry.”

From the comparably small amount of research dedicated to Hilma, there is a tendency to summarize and dismiss her as a sort of hermit witch lady. However, from just my brief time contemplating her work and life, I am astounded at how potential there is in art criticism and history to unpack and discover more about Hilma Af Klint’s world. It is just a fact that there is not enough attention devoted to her. As an artist who was censured by society and secluded herself in order to dedicate her life to creating artworks that transmitted spiritual messages, it is necessary that we direct more attention to the study of her works. It's hard to believe that Hilma Af Klint’s works were made over 100 years ago, she really did paint for the people of the 21st century.

The series Tree of Knowledge has been acquired by Glenstone Museum in Potomac, Maryland.

References

Birnbaum, Daniel, and Enderby, Emma. “Painting the Unseen” Painting the Unseen. Serpentine Galleries Koenig Books. 2016

Higgie, Jennifer. “Longing for Light: The Art of Hilma Af Klint” Painting the Unseen. Serpentine Galleries Koenig Books. 2016

Voss, Julia. “Hilma Af Klint and the Evolution of Art” Painting the Unseen. Serpentine Galleries Koenig Books. 2016