Feature by Sophia Ricaurte

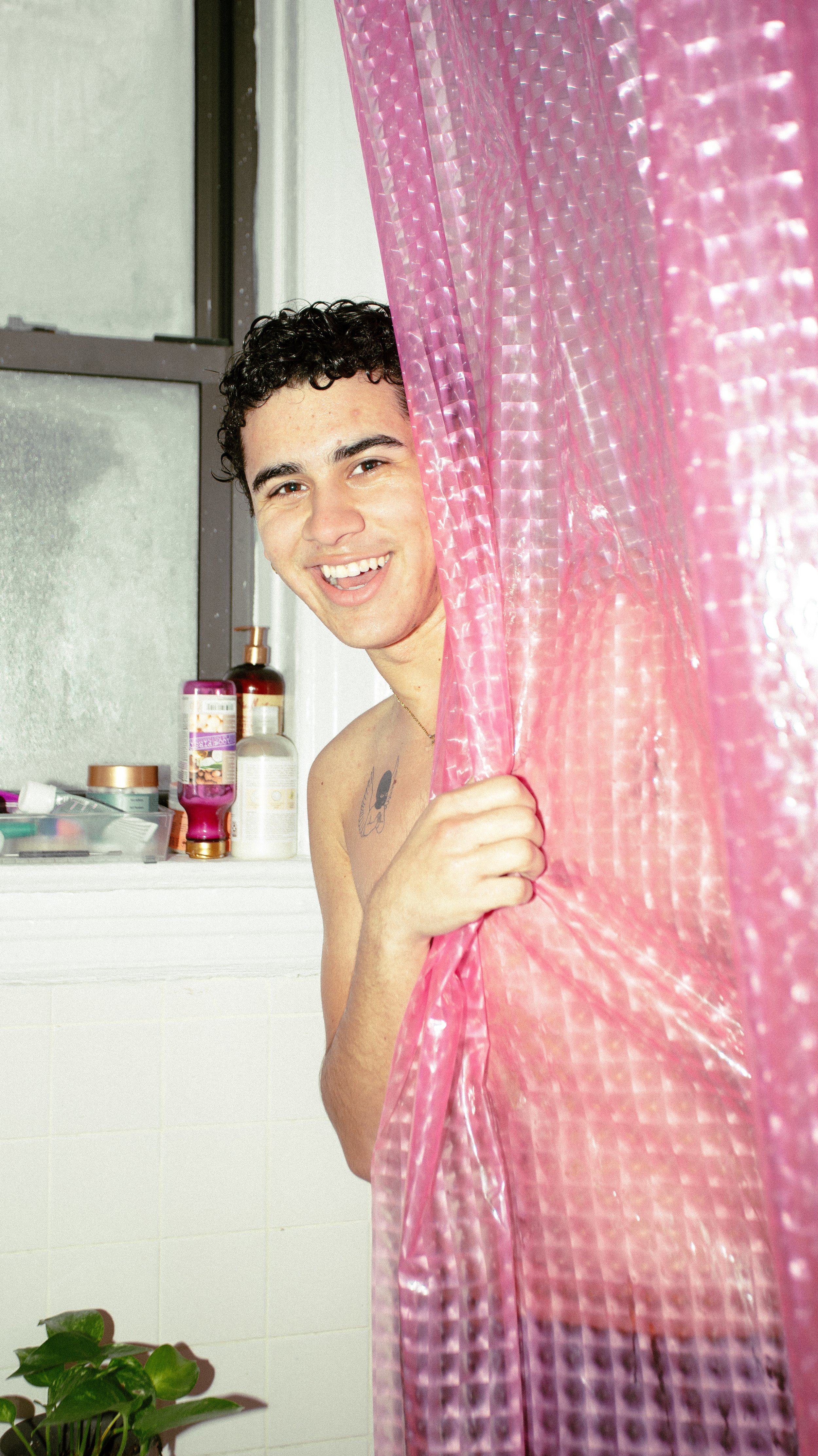

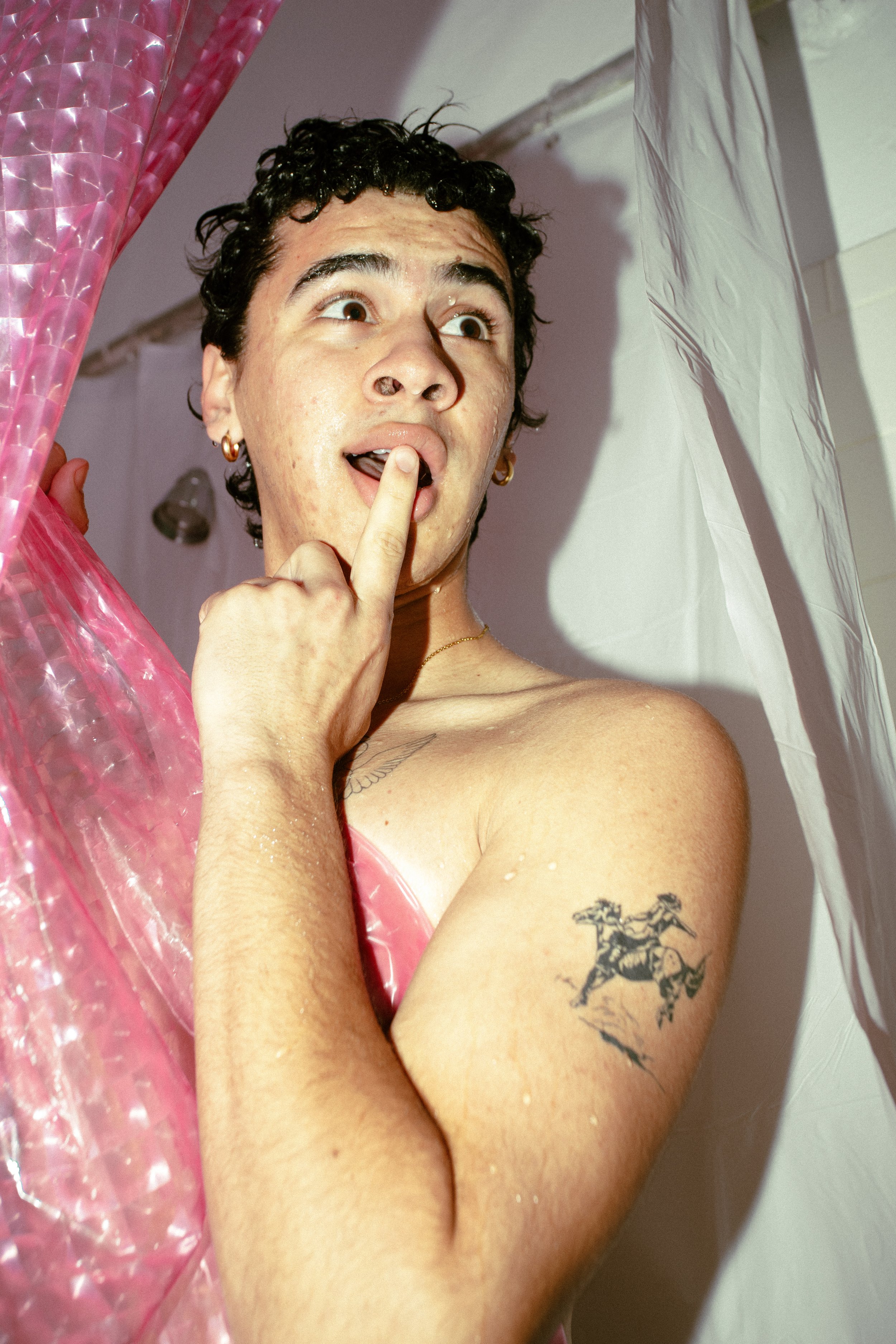

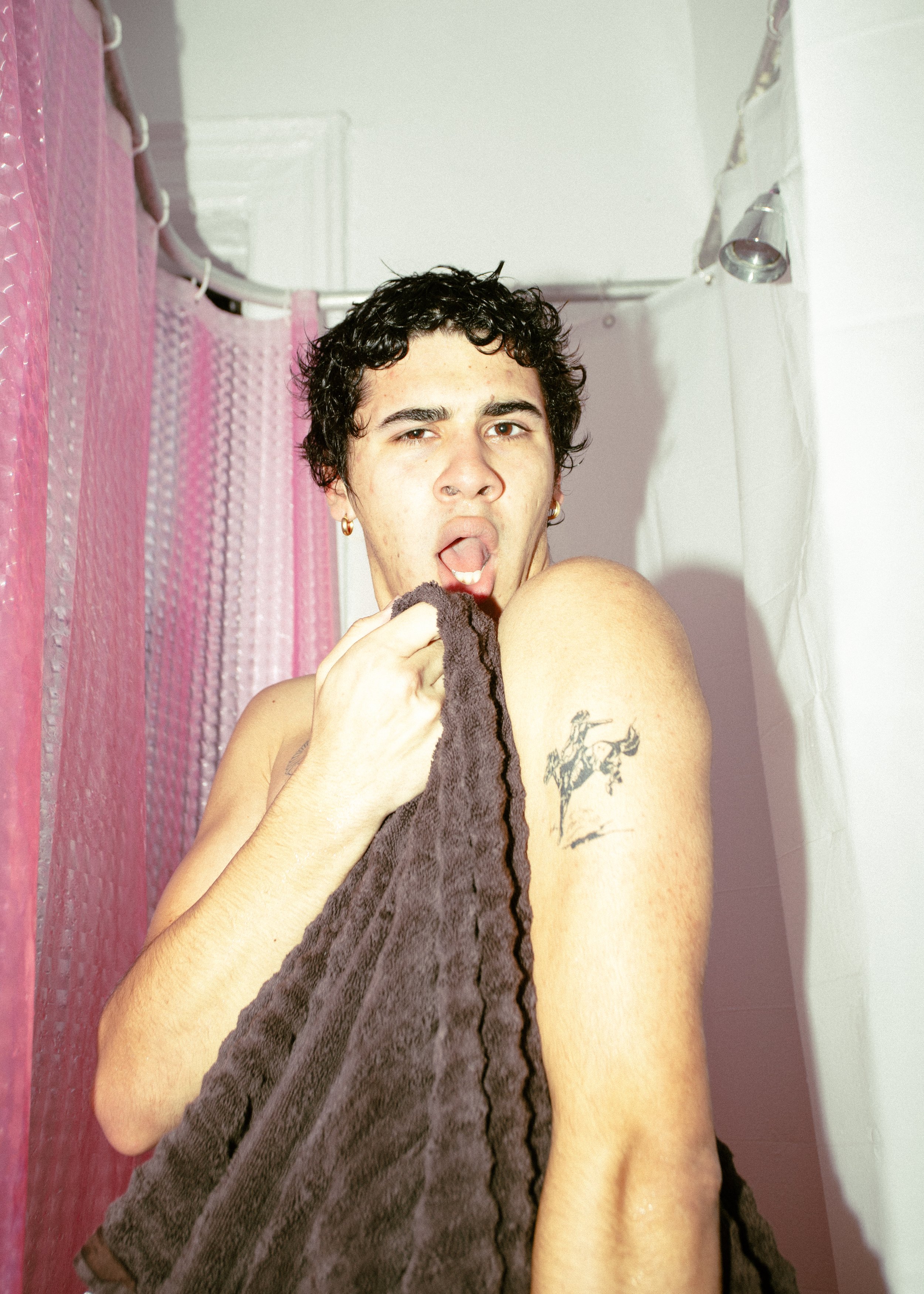

Photos by Dennis Franklin

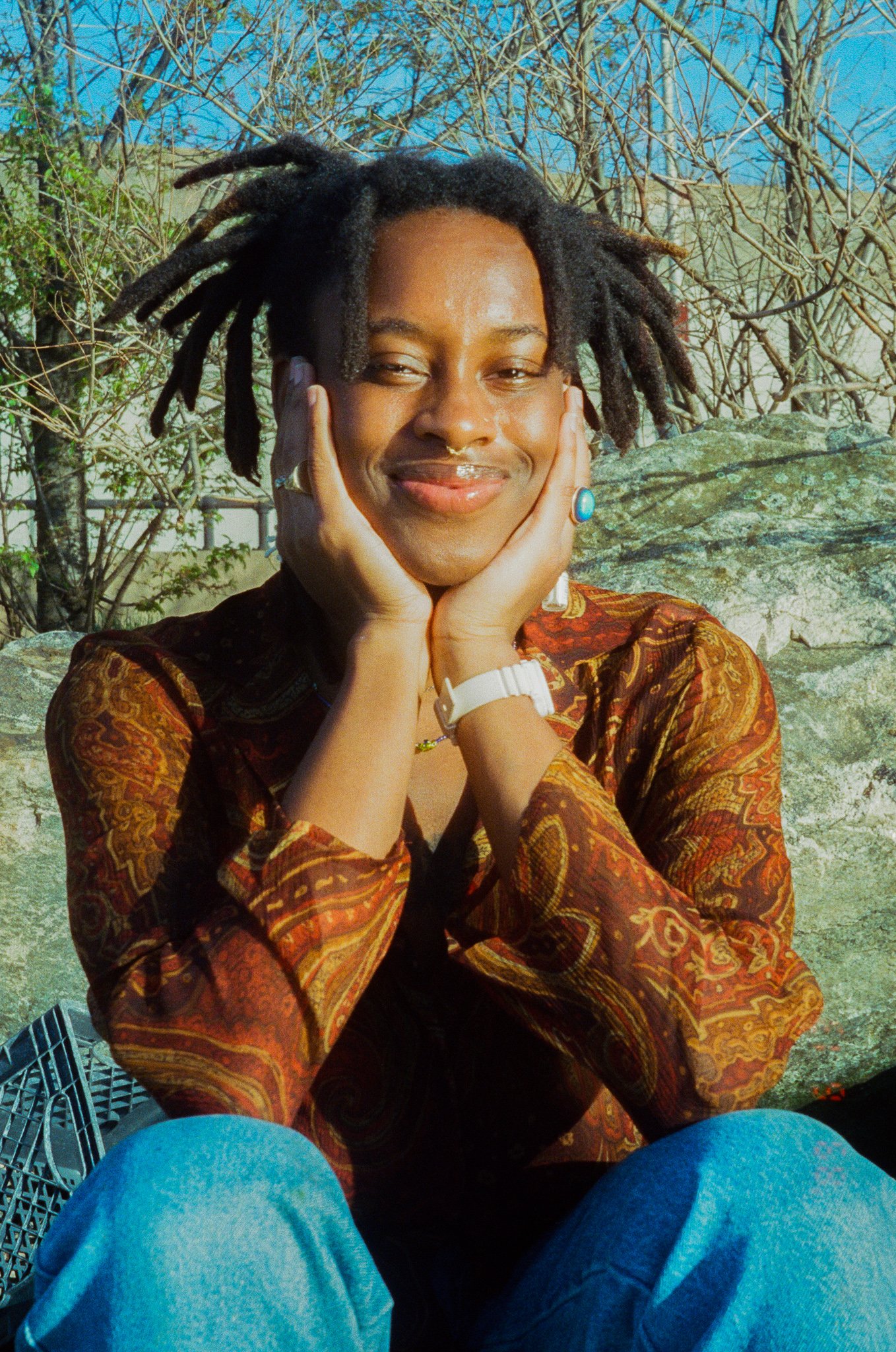

Shiloh Tracey (he/they) is a multidisciplinary creative based in New York City. Exploring the intersections of oil painting, collage, textiles and performance, they channel artwork which explores intergenerational and intercultural healing, ancestral knowledge, Black and queer subjectivities, and ecology.

This interview was conducted on an April afternoon at Riverside Park, looking toward the Hudson, sitting in the rain.

How do you like New York?

I love New York. I’m a New Yorker by heritage. My grandfather moved here from Jamaica when he was young, and my parents and grandparents grew up in the city. I don’t know how much I’ll like the pace when I’m older, but right now, I like the dopamine rush, I love clubbing, going to concerts, park walks, running into friends, getting up early before everyone else is awake. I try not to stress myself out or rush to get anywhere. On the flip side of that joy, there is pain, loss, and existential terror. COVID cases are rising, so I’m planning to go out less. Historically, Black communities are being priced out of their original neighborhoods by gentrification, and I’m interested in abolitionist alternatives to our current policing system.

How would you describe your background?

I’m Caribbean-American and was born in New Rochelle. I’m trying to learn more about my ancestry, often by going through old photographs. I’ve been interested in art since I was very little and started painting seriously my junior year of high school. I’ve been going to PWIs my entire life. I went to a private school in Baltimore for K-8, and then boarding school in New Hampshire. I identify strongly with my Blackness, with my queerness and my transness. My upbringing as someone who was socialized as a woman also largely plays into how I observe myself in the world. But all of these identities are not who I am at my core. They define me in some ways, but beyond that, I’m an artist with friends who have helped shape who I am. They’re rockstars. Hopefully I've helped shape them, too.

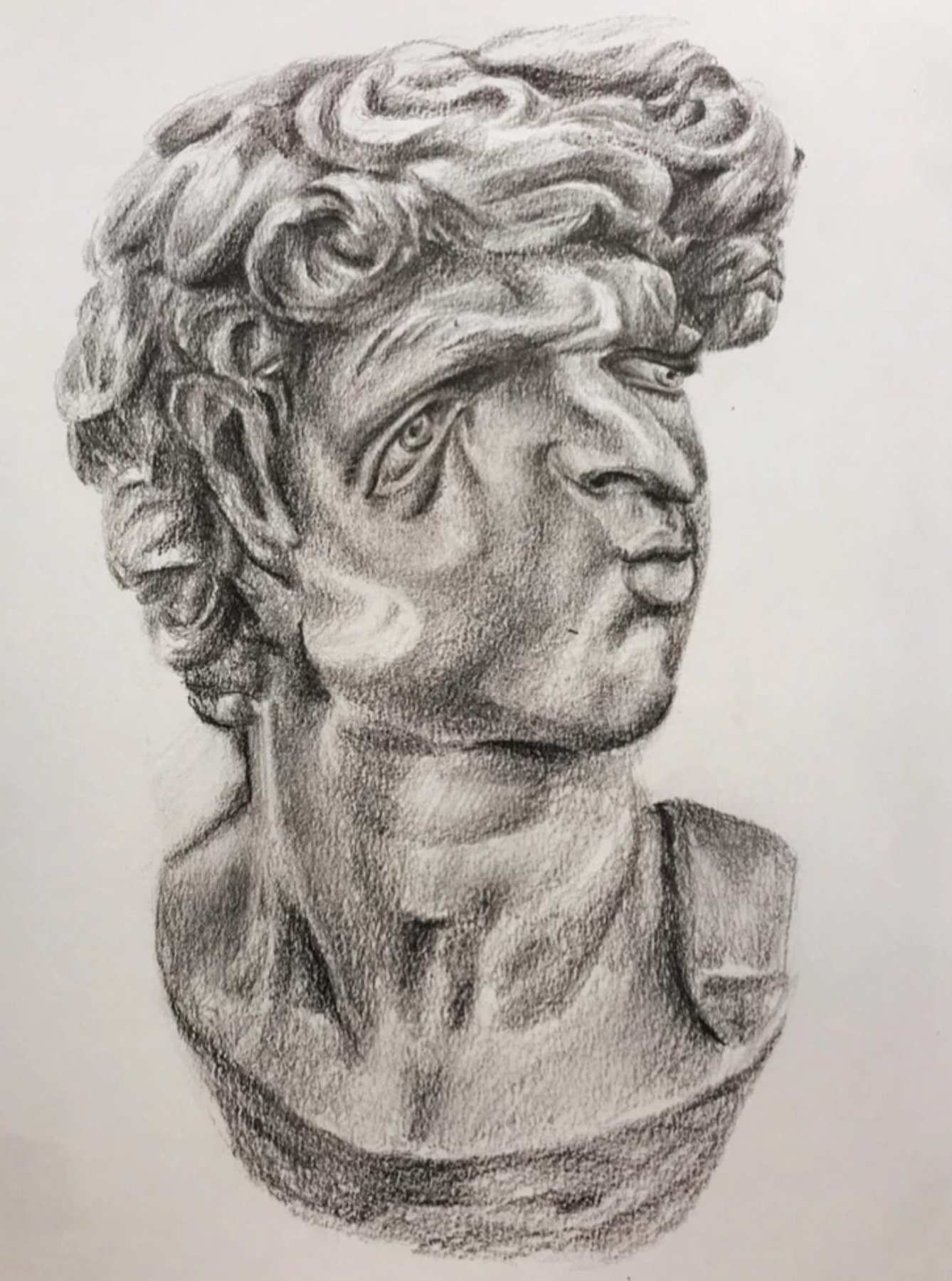

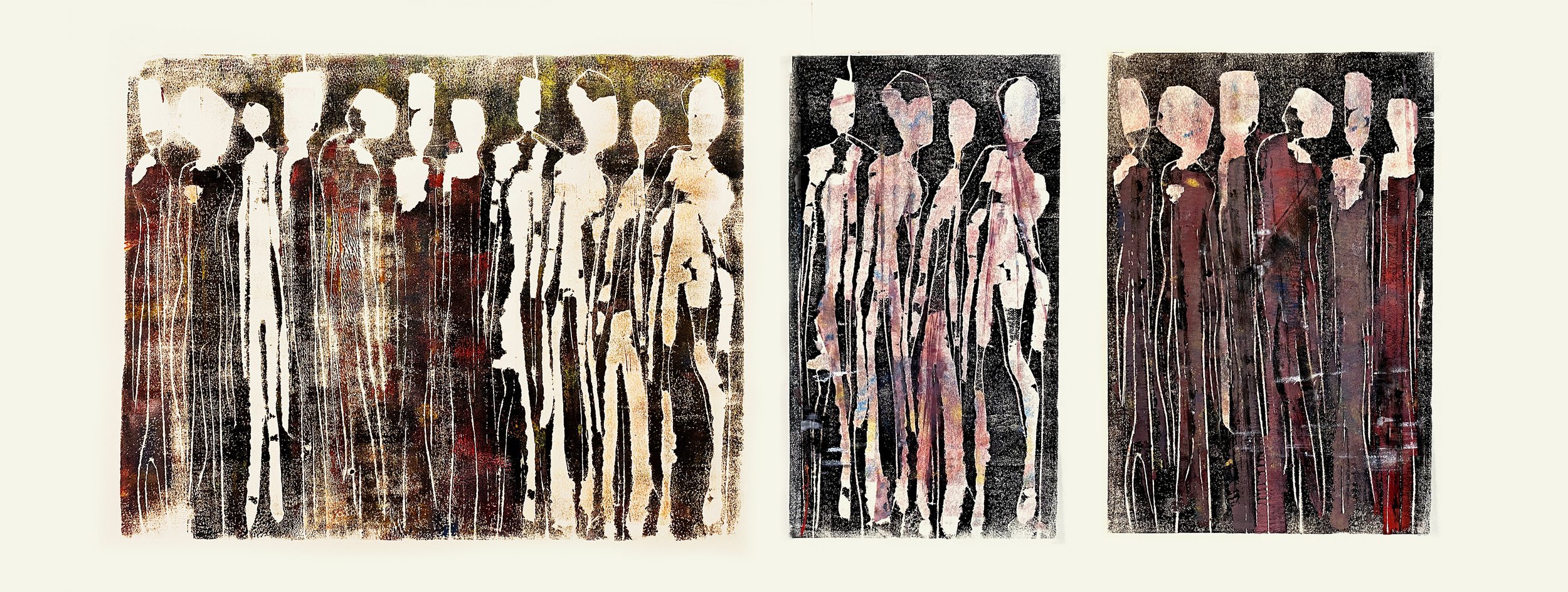

My Mother’s Child

Who are your influences?

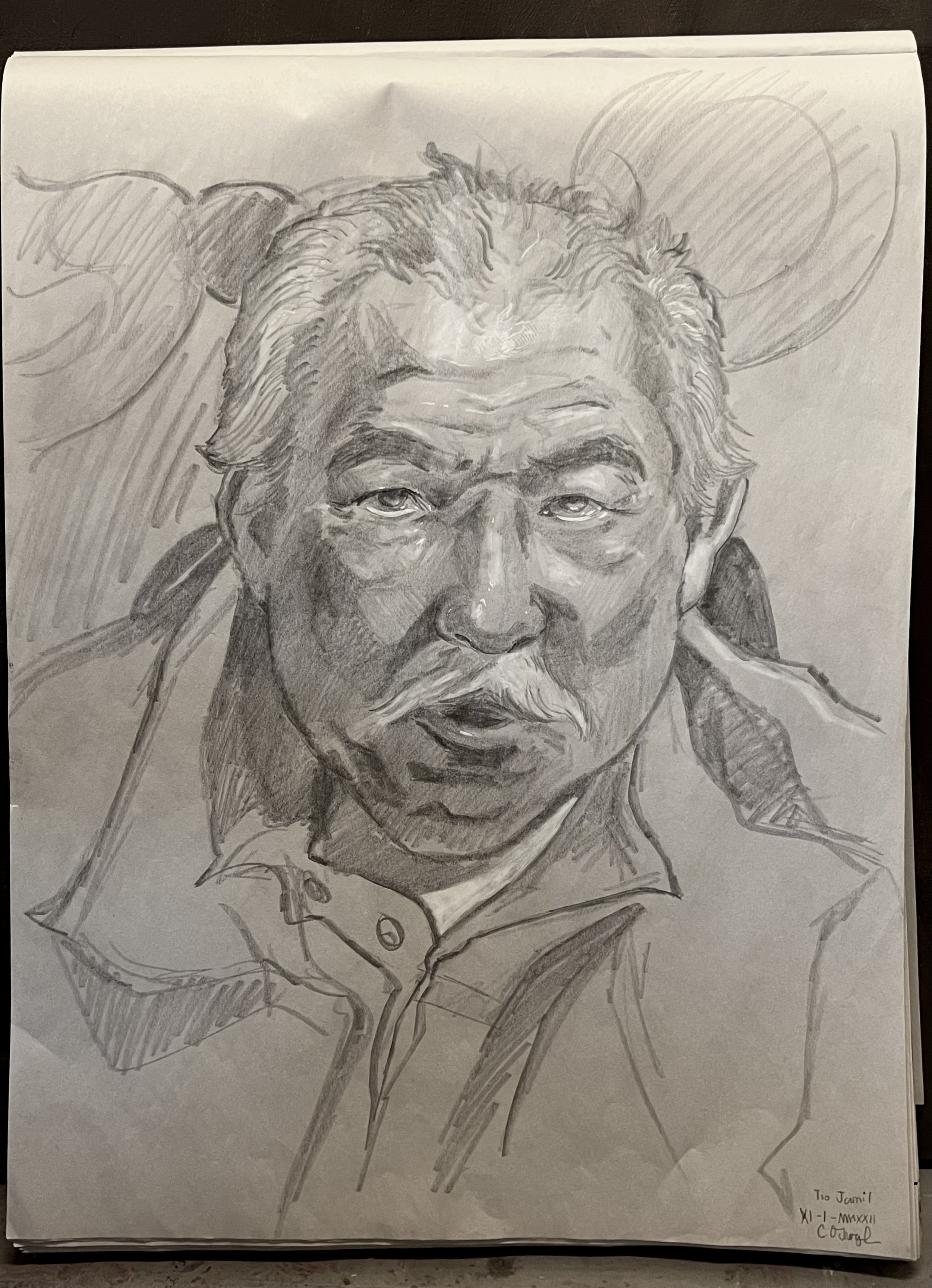

I have many influences in music, writing, and visual art. Lygia Clark is an inspiration of mine from Brazil. She worked on proposições: incorporating viewer participation. I love The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel van der Kolk. Also Julie Mehretu, who describes her abstract work as a “time-based experiential dynamic.” Brene Brown helped me see true growth that empowers and humbles and does not respond to punishment. My mother is really important to me and so is my younger sibling Gio, who makes music @nonamedugly on Soundcloud. There are others: Ottessa Moshfegh, Haruki Murakami, Junot Diaz, Pat Parker, June Jordan, Joy Harjo, Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, CAConrad, Coyote Park, Faith Ringgold, Kara Walker, Hilma Af Klint, Diedrick Brackens, Héctor García. I could go on and on.

Do home and religion converge for you?

The earth is my home. My first performance art piece was literally called Earth Church. Pre-high school, I would attend Catholic church with my father and his girlfriend before I stopped having contact with them. I would also attend Buddhist convention centers and visit other practitioners’ houses with my mother. In high school, I would go with my then-close friend Ahlam to the Muslim Students’ Association every week. I’ve always enjoyed the iconography of religion, and I feel at home in the bigness and painstaking intricacy of churches and other sanctuaries. I love the Sagrada Familia in Barcelona, a one-hundred-year project. It embodies the kind of intention I’m seeking to nurture in my work. I don't focus on doctrinal religion and don't believe in any one religious institution. What I do, say, and believe is setting myself up to be at home in any place, especially because I was constantly moving when I was younger. Making a home, for instance, out of these tiny rooms in my high school and college dorm rooms, where only my furniture stays the same.

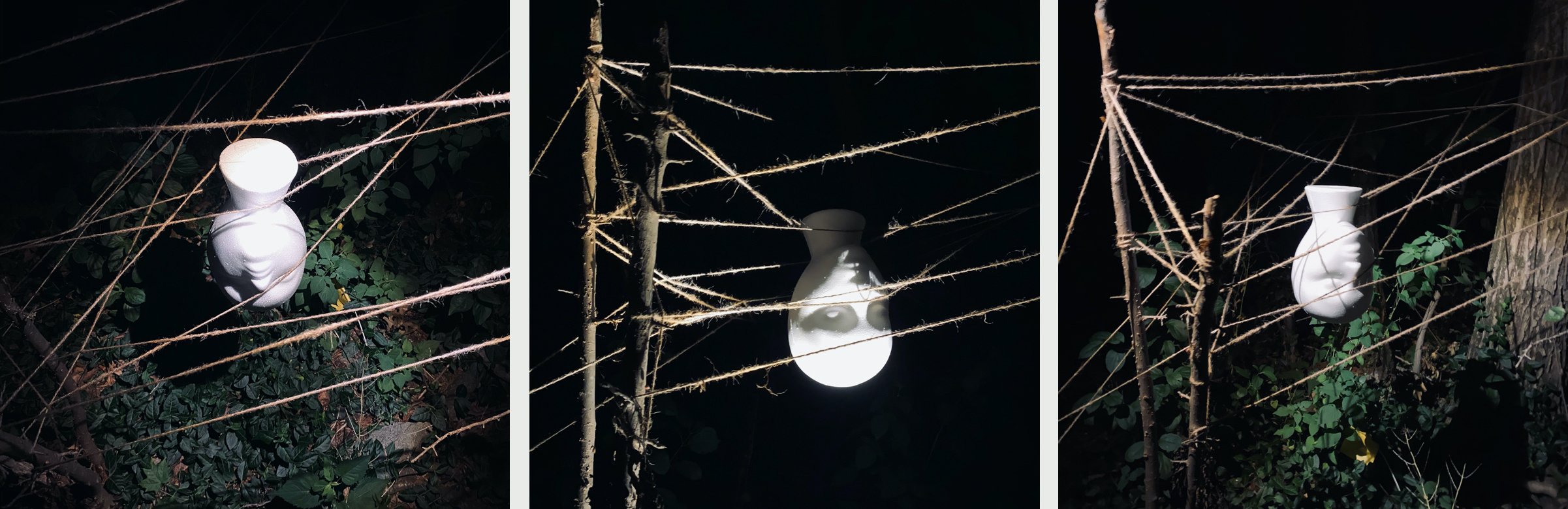

I actually wanted to ask you about “Earth Church (Pacifist’s Polemic Against the Lawn)”. Could you say a little about the piece and its inspiration?

It’s hugely inspired by Robin Wall Kimmerer, who wrote Braiding Sweetgrass. She talks about personhood in indigenous societies, not just humans, but plant and animal life: everybody in one network, all deserving to be communicated with. Before the performance, I kept seeing “lawn renovation” signs around campus. Space is so hard to come by in the city, and here was so much being used for show. In the US, there are around 40 million acres of lawn, used to grow one plant we can’t even eat. I had everybody lying down on the lawn around me in a circle. It was an invitation to feel close to the depth of the investment in this fear-based project.

Earth Church (Pacifist’s Polemic Against the Lawn)

I feel like I often connect the natural world with the divine. Could you tell me about your sensibility in the divine?

There is felt-knowledge that’s passed down. My loving relationships allow me to expand this safe space within myself, where my soul holds hands with God. It’s a space which contains the world within it. Occupying that space puts me in touch with past selves that I abandoned somewhere along the path. I started reading tarot this year, it’s a process of communion with your personal symbolisms and a way of developing trust in what you’ve seen and observed, and also trust in what you cannot see that is influencing your life. I’ve had some really insightful readings thus far on my own.

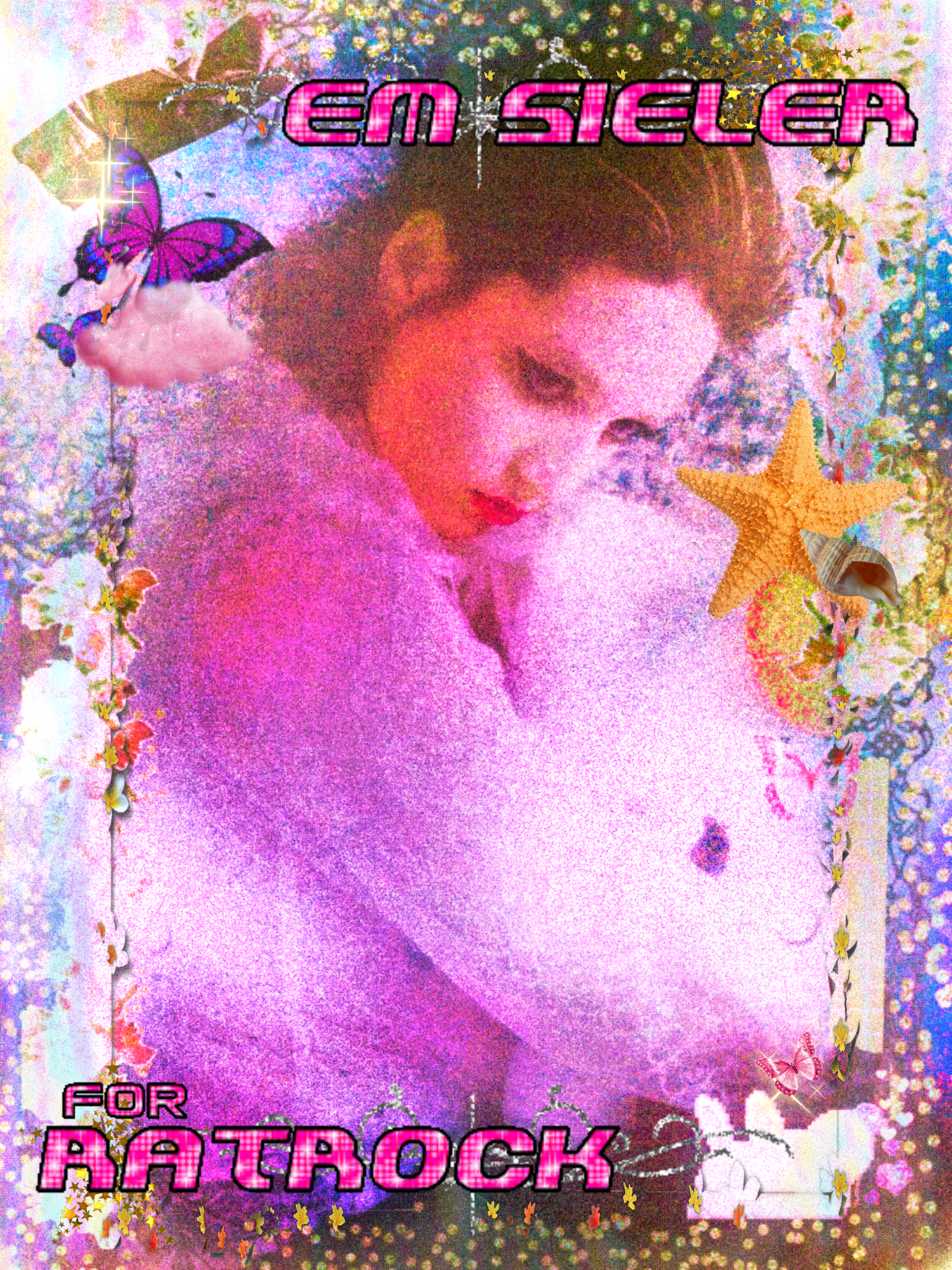

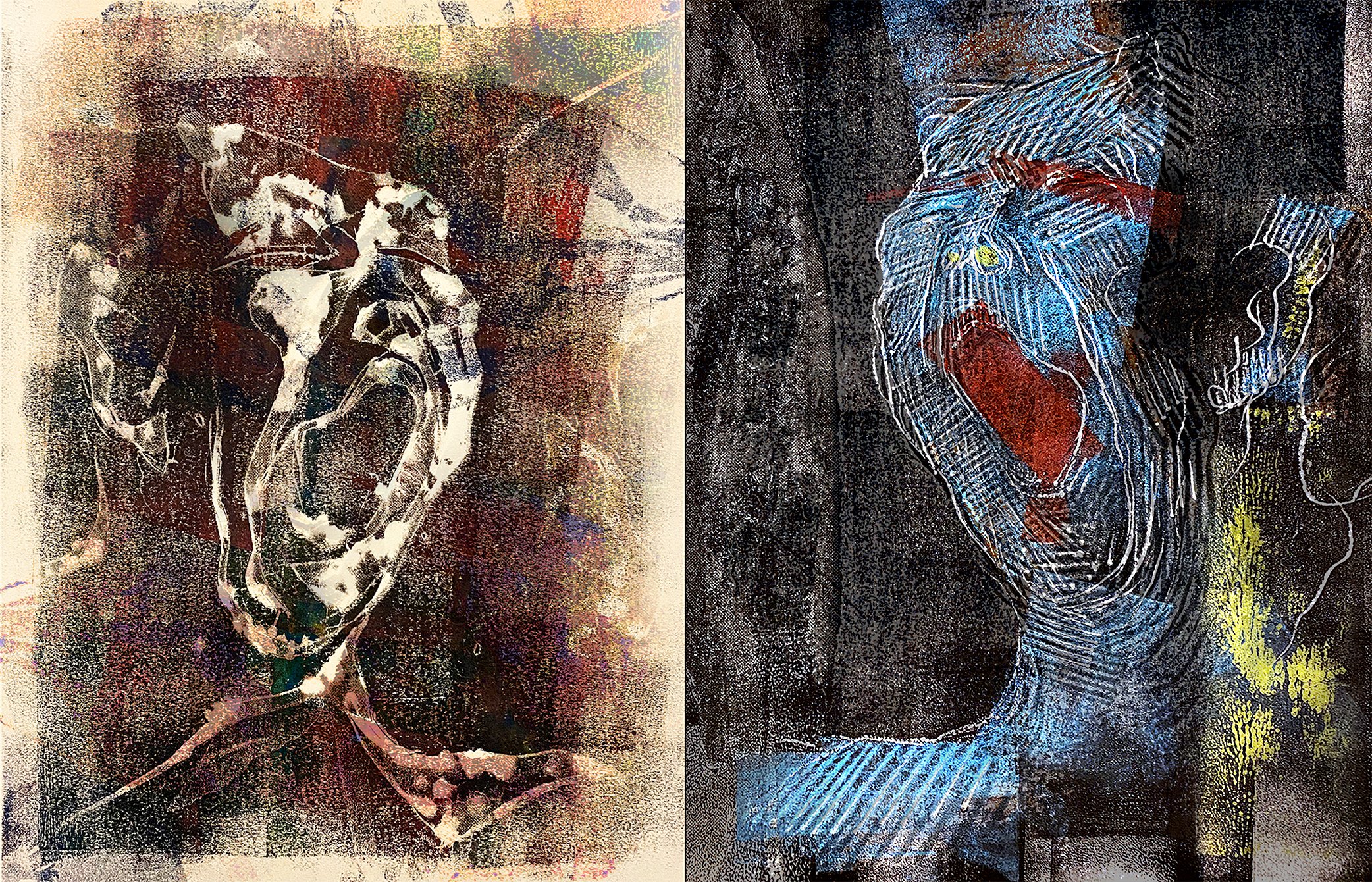

Lovers in Blue

What’s your relationship with feminism?

My relationship with feminism has saved my life. I feel that way about many socio-political movements, but especially feminism. I ran an intersectional feminist club in high school with my really good friend Chinasa: my queerplatonic life partner, they’re actually the only other person I’ll trip with. We were both learning about our own capacities as leaders within an institution that didn't always appear to be friendly to or accommodating of the voices of Black folks, queer folks, and women. We were exercising our power from this love-standpoint, and that’s where I first started reading bell hooks, who is a main pillar of my feminist thought. I've been out as trans for two years now, and I started testosterone during that time, and went off of it because it didn't feel right for me anymore.

Much of my identity is just going to be for me and my most intimate relationships. Sometimes, someone’s idea of a woman is inclusive of me as a tall Black person, other times, it’s not. It’s tricky. I also have had to steer clear of white feminism, which collapses all experiences of perceived womanhood and doesn’t take into account the nuances of privilege based on other factors. Transfeminism has been an incredible tool for me to locate myself in the world. I love Sylvia Wynter’s posthumanism. She’s a Jamaican philosopher who argues that the concept of the human itself is problematic.

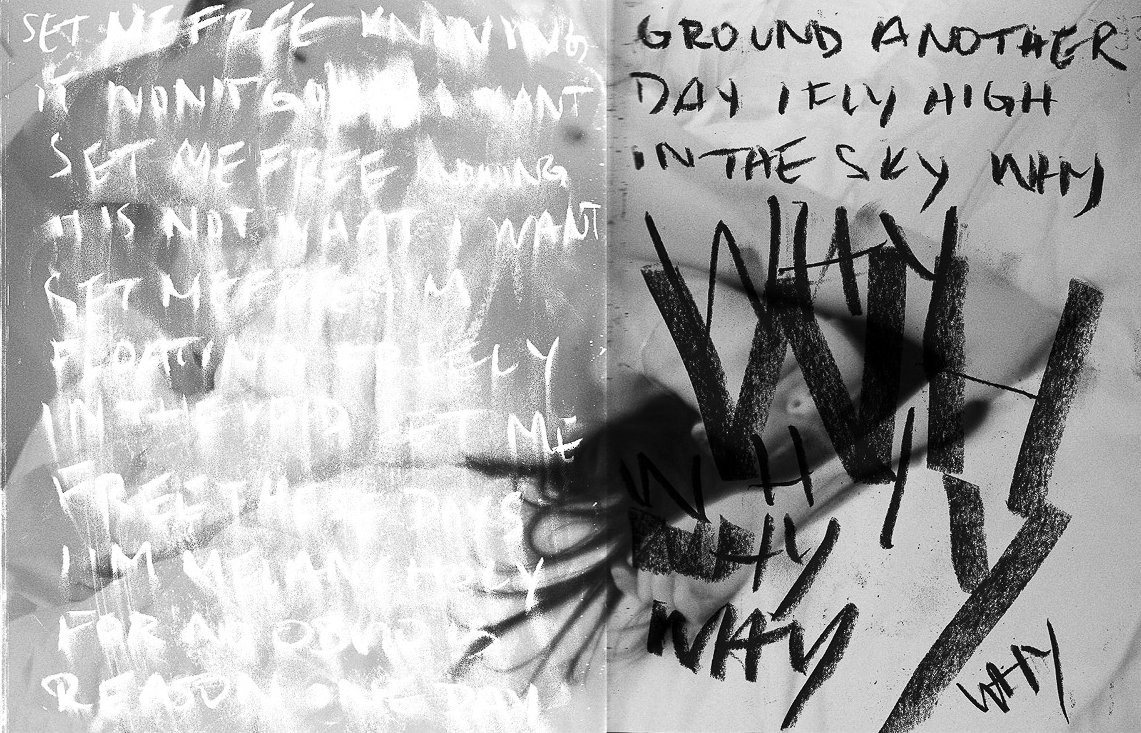

How Do You Know What Your Body Is

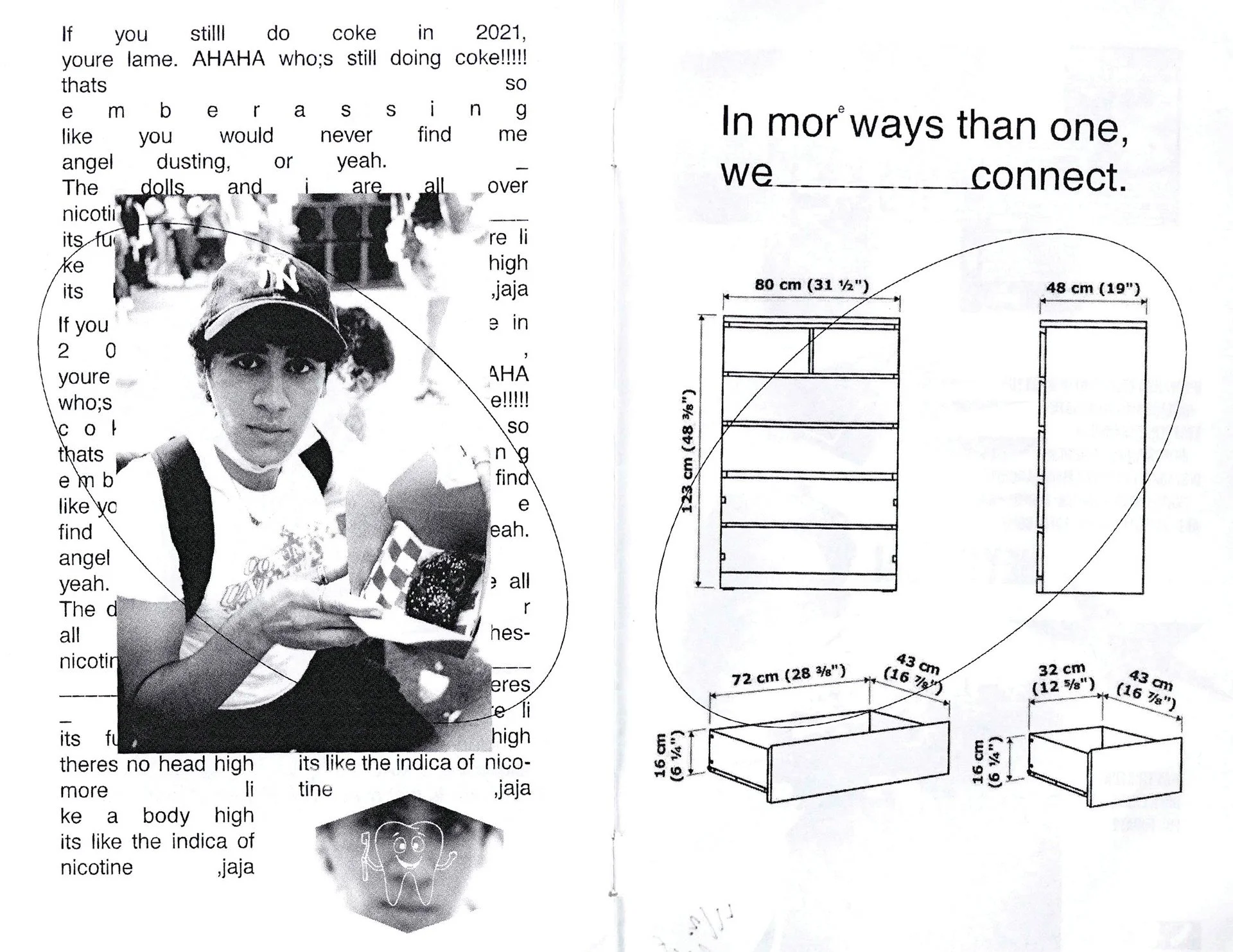

I asked that question because it’s a preoccupation of your zine “How Do You Know What Your Body Is?”

My zines were a major place where my poetry and visual arts began to intersect. The first time I called myself a boy was in my zine, which felt really good.

BOY* Black Transmasc Reflections

That’s really amazing. What are you working on right now?

The zines were published maybe six months after I came out. I'm planning to work on another one on gender that addresses the shape-shifting I feel in my transness. This year, I’m focusing on expanding into abstract art. A lot of my poetry is about animals, social feelings, spirituality, and the Atlantic Ocean. I'm also really thinking about my senior thesis on cycles of birth and rebirth, the ephemeral nature of our world, and the things we treasure. That’s something my ex Beth and I talked about on our first date; they inspired me to do performance art and did a piece where they got legally married and divorced to someone they met on Hinge all within a month or so. My art answers a question that my body is living right now: what happens when I cultivate a gentle observation of myself, and turn it inward towards the unconscious realm within me? I’m thinking a lot about questions my body has posed to me throughout my life. Through my art, I’m investigating my body as living history. I’m making art that believes in humanity's longevity, and that in itself is prayer: creating at all, hoping somebody will be around to see it tomorrow.

Wow. What do your creative processes look like?

They’re very spontaneous. I’d like to systemize my process a bit more and figure out how to be more methodical about it, but for now it changes from piece to piece. It’s important for me to create an environment to be in tune with the expansiveness of my being, avoid people who cannot honor me in my fullness, and be accountable to others without being overly responsible for them or abandoning myself. I keep a dream journal and two life journals. I draw good energy from spontaneity, and I don't want to lose too much of that.

What are your current obsessions?

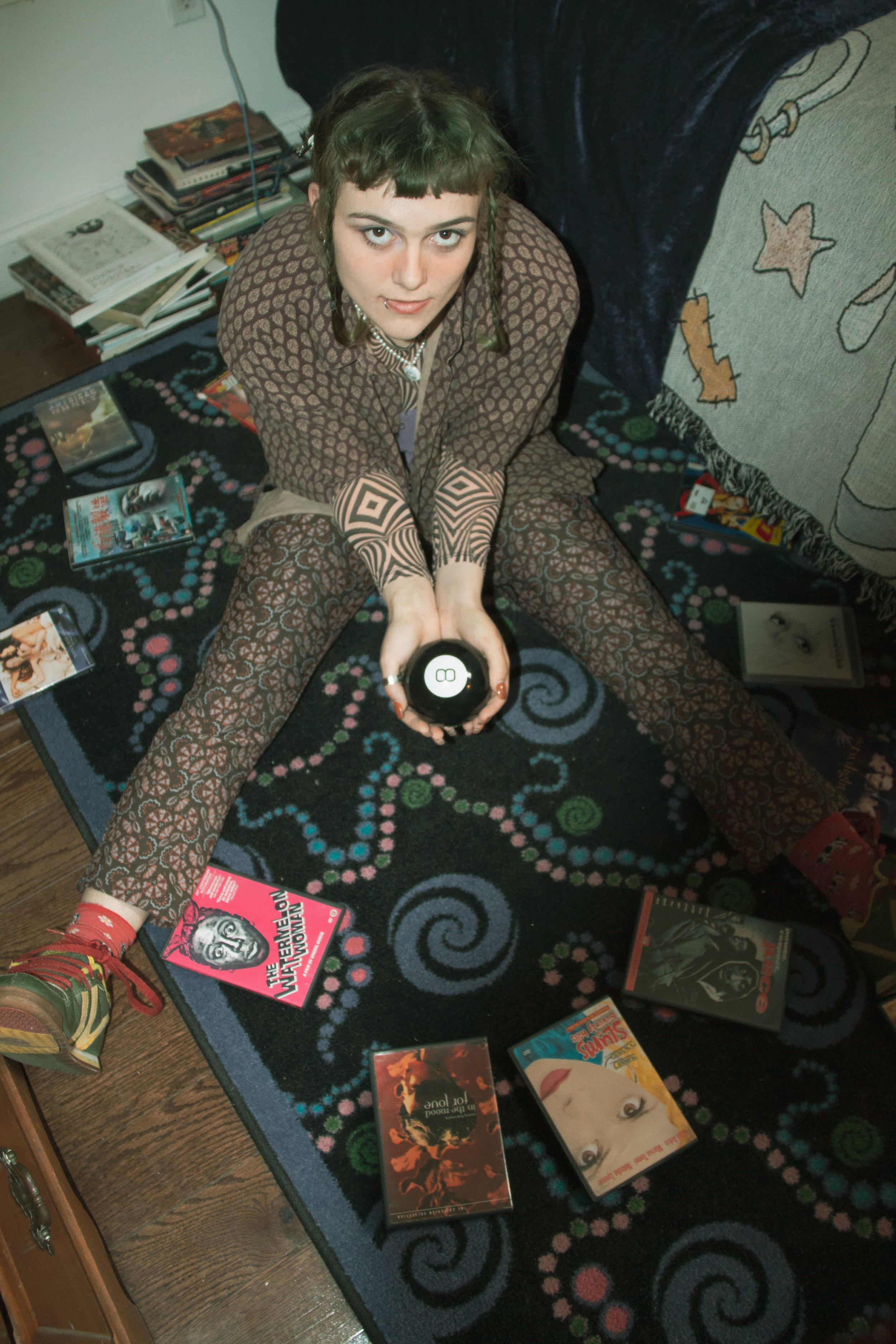

Noticing and creating small kindnesses, not holding onto the resentment of space not being made for me, instead deciding to simply hold it for other people in small ways each day, and the universe pays that back to me in kind. There’s a poem about this called “Small Kindnesses” by Danusha Lameris. They’re not these grand, massive gestures but they kinda are? I also started learning to stick-and-poke this year, “angel” is in script on my leg. I love my good friend and suitemate Chrystal’s Ghanian stew, and I’m collecting movies to watch outside of the American mainstream. Two I’ve really enjoyed are Xala, directed by Ousmane Sembène and Wong Kar-Wai’s In the Mood For Love. I want to watch Chungking Express at some point, and Cinema Paradiso, a movie about memory directed by Giuseppe Tornatore. I’ve been watching a lot of Sailor Moon lately. I love Akira and have watched it several times. It incorporates the same chanting that I did when I practiced Buddhism as a child, and I love how grotesque the animation gets.

I love that. Can you tell me something about the role of sound in the context of Afro-diasporic and Buddhist traditions in your art?

I'm inspired by free jazz and how completely unintelligible it is. It denies musical structures and still calls itself music. I played piano for six years, and used to be in a jazz band. Jazz and abstraction are rebellious. Abstraction especially in the 60s was a huge fuck you to the art establishment. One of the things that marked jazz as a style was how it brought people together. It’s a creole genre basically, taking inspiration from both Europe and Africa. I do a lot of field recordings of soundscapes: sometimes water or rain. Soundscapes accompanying each of my paintings is something that I might try to do in the future. The jazz artist Nala Sinephro inspired me to hone in on inner silence. I’m trying to incorporate more stretches of time into my life where I just don’t speak, write, produce anything or communicate with anyone. Silence feels like a place where I don’t need to prove myself or speak to have an impact.

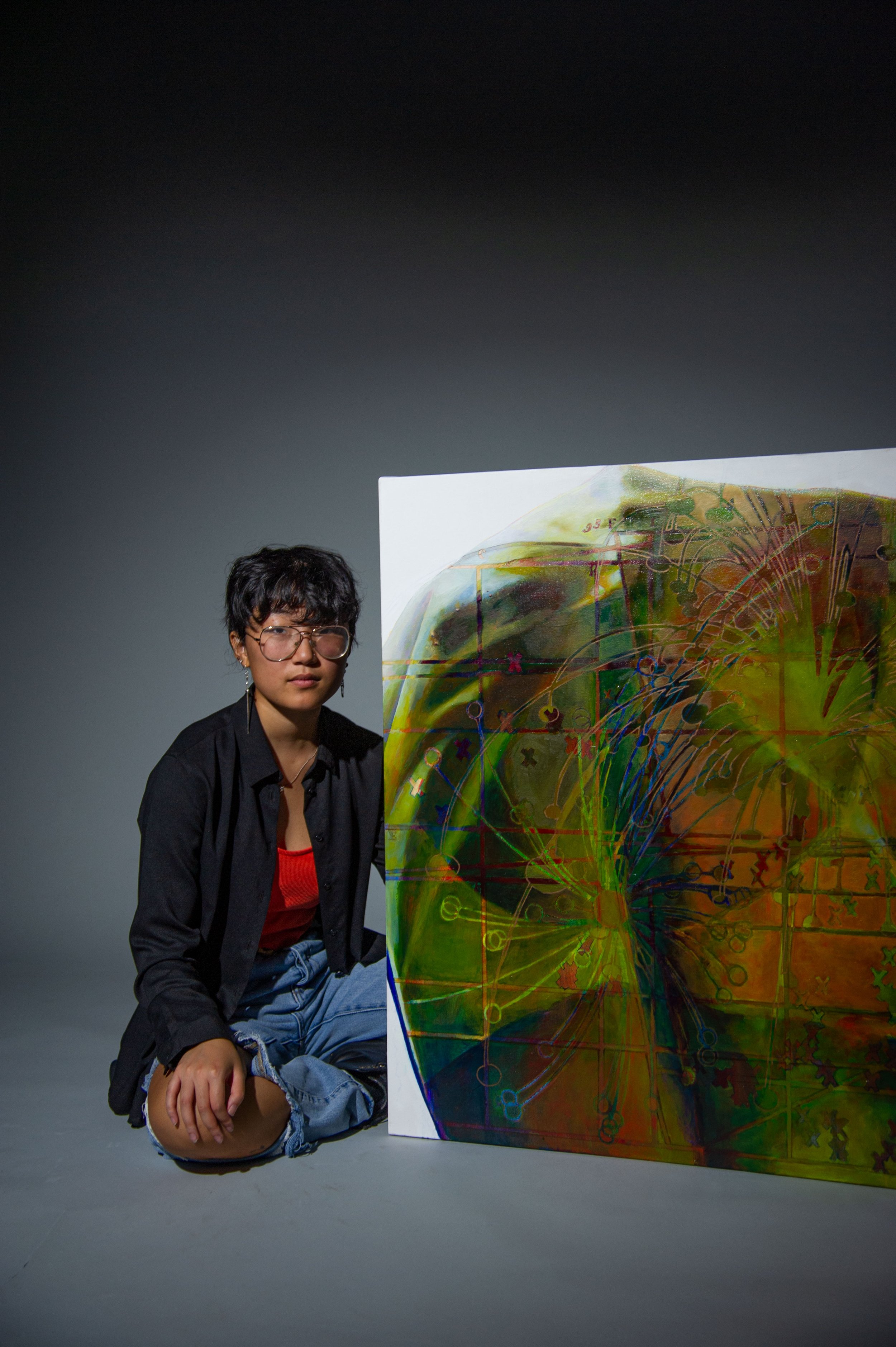

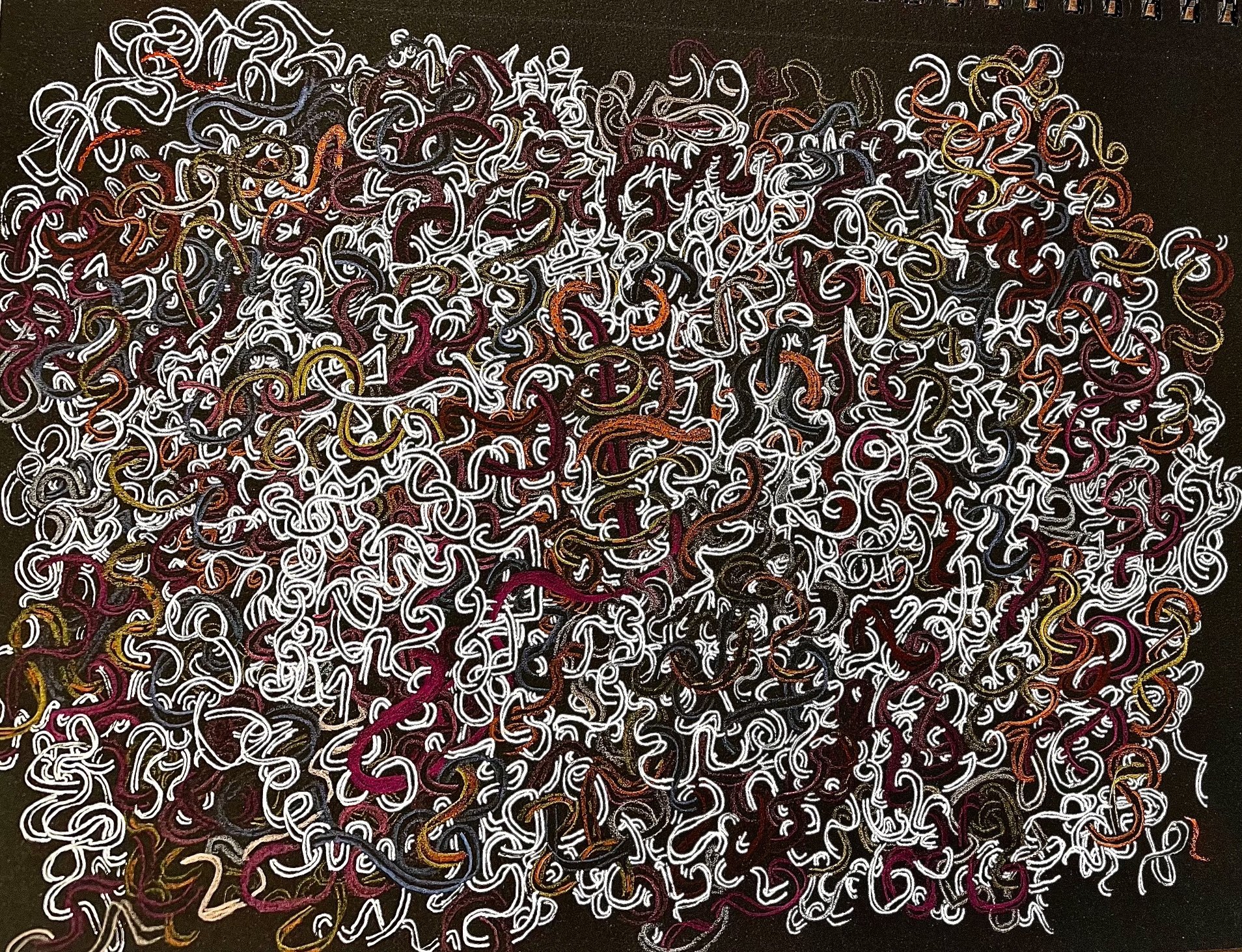

Gut Wheels

What does healing feel like to you?

Healing feels like trusting myself, that I have agency, taking my drive seriously, that I exist outside my pain. It feels like believing my own experience—not looking to others to define that for me. Letting people who don’t know me well be wrong about me─not trying to chase down and correct all my afterimages. Trauma can make you believe that the whole world is out to get you, that you'll never find opportunity anywhere. Connecting with my ancestors in spirit is constitutive to how I heal. I try to build up the structures internally and make the connections externally to seek out those opportunities to carve out a life for myself, even when it feels really difficult. My body lets me know where it wants to spend my time, so it’s also about listening.

Where do you see yourself in the future?

I would love to do a solo show. There are galleries that allow you to rent out space for a month and keep the cover price of anything you sell. Freelancing is my dream. If not that, then being an art or Spanish teacher or art therapist. But I'm mostly thinking about which one of those positions will allow me the most time for art and potentially travel.

You’re incredibly inspiring, Shiloh. Where can we find your work?

Thank you so much! On instagram @shilohtracey.jpeg and my substack poetry can be found here.